There was plenty of suspense Sunday evening in Hamburg, Germany’s second biggest city. Would the mayor, Ole von Beust, win a majority again and keep ruling the city-state without requiring support from any other parties? Or could the Social Democrats, possibly with the help of the Greens, overtake him and regain control of a city which they had ruled for many decades?

But the biggest question was: could the young party called The Left, whose predecessor, the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), was never able to break out of its East German strongholds, now continue its march westwards with the aid of the young new western group it had joined up with? Last spring it won its first seats in a West German provincial legislature in the city-state of Bremen. Then in January, in two sensational election campaigns, it won seven percent of the vote in Lower Saxony and just above the required five percent in Hesse, thus getting deputies in both. Would it continue upsetting worn-out apple carts in the city-state of Hamburg as well?

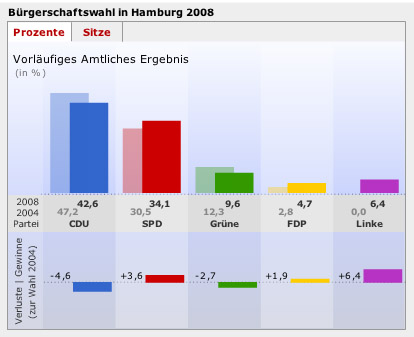

It sure did! On Sunday it won just about 6.5 percent, meaning 8 seats in the provincial legislature.

SOURCE: “Die Wahlergebnisse in Hamburg,” Der Spiegel, 24 Febraury 2008.

The results of these victories are far more important than the single digit results would indicate. Until now, if no one party had an absolute majority, the provincial governments were often ruled by a coalition, usually either the two right-wing parties, Christian Democrats and Free Democrats, or the two supposedly left-of-center parties, the Social Democrats (SPD) and the Greens. Sometimes, when this didn’t add up, the two big parties, Christians and Social Democrats, would join to form a Grand Coalition. This is what happened on the national level with Angela Merkel and her CDU sharing the government with the SPD.

But in Hesse it hasn’t worked out. The SPD there can hardly join with the Christian Democrats, whose head, Ronald Koch, ran an extremely nasty campaign based on hatred toward “foreigners,” especially young immigrants, which almost descended to the level of the neo-Nazis. The SPD leader fought him very hard and tried to sound more leftish than usual. But alas, the Greens did not win enough seats to form a government with them either. The only logical conclusion would seem to be a coalition with the Greens but with The Left agreeing not to vote against it. The Left offered this solution.

But the SPD had sworn never to work together with those nasty Left people under any circumstances. Weren’t they mostly old Communists from the East or renegade Social Democrats from the West? If the Social Democrats stuck to this pre-election pledge, they would automatically bar themselves from ruling Hesse and Ronald Koch might stay in power. A few SPD leaders have begun to weaken — and approve an agreement with the Left — while others showed outrage at the idea. It is still up in the air.

And now Hamburg. With the entry of The Left into the city-state legislature, nobody has a majority here either. The Christian Democrats lost votes but remained the strongest. Since their buddies and allies, the Free Democrats, got only 4.8 percent of the vote, they are out of the legislature and out of the running altogether.

This leaves the city with only three choices. The Social Democrats could join the Christian Democrats in a Grand Coalition like the one on the national level. But they hate the idea. Both big parties are busy jockeying for position ahead of the next national elections in 2009, and the SPD is trying to lose the bad reputation it earned of turning to the right, placating big business at the cost of working people, policies which have been sending more and more of its members and supporters to The Left.

The second choice would be for the Greens to swallow any and all remaining principles and form a coalition with the Christian Democrats, giving up their main planks on equal education for all and stopping further pollution. This would be the first such coalition on a provincial scale and would surely cost them a large number of their grassroots membership all over Germany, often sending them leftwards.

The third choice, as in Hesse, would be for the SPD and the Greens to form a coalition with an agreement for The Left to support them. Of course this would mean giving The Left a veto power over any reactionary decisions they might come up with. If they avoid any more such rightward moves, they would be OK. And this arrangement is the only way for the SPD to get back into leadership. It would naturally require an alteration of long established red-baiting.

Before the Hamburg election, the leading candidate of the SPD, Michael Naumann, a well-known publisher, said he would never work with The Left (he said: “Nein, nein, nein, nein, nyet” — his attempt at either humor or irony). Will his party keep to this position, cutting off its nose to spite its face? Or will it overcome its prejudice and face up to the fact that Germany’s voters are sick of the corruption, the lopsided economy with its growing hardships and widening income gap, and the giant expense of foreign military ventures? And that they seem to be moving leftwards?

Of course, below-the-belt attacks against The Left are increasingly prevalent in nearly all of the media. Many old-time politicians are getting more and more worried about a development they can no longer ignore. And with The Left winning such first-time victories in one province after the other and already gaining first place in opinion polls in the five East German provinces, this situation may well dominate the national elections next year. Almost anything is possible.

Victor Grossman, American journalist and author, is a resident of East Berlin for many years. He is the author of Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).

|

| Print