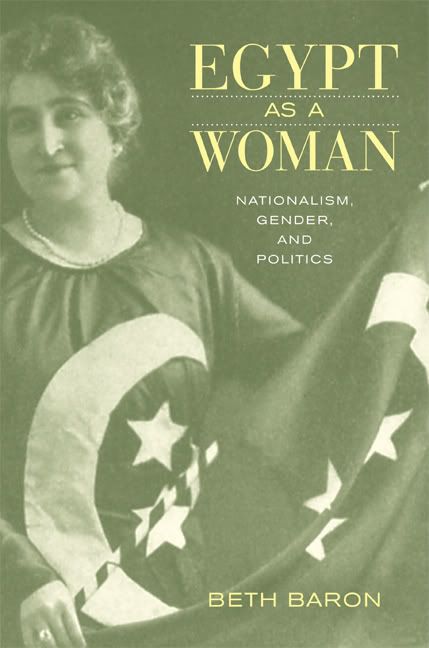

Beth Baron. Egypt As a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. 292 pp. $60.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-520-23857-2.

In Egypt as a Woman Beth Baron explores the connections between Egyptian nationalism, gendered images and discourses of the nation, and the politics of elite Egyptian women from the late nineteenth century to World War Two, focusing on the interwar period. Baron builds on earlier works on Egyptian nationalist and women’s history (especially Margot Badran‘s and her own) and draws on a wide array of primary sources such as newspapers, magazines, archival records, memoirs, literary sources such as ballads and plays, and visual sources such as cartoons, photographs, and monuments, as well as on the scholarship on nationalism, feminism, and gender. This book can be read as a monograph focused on the connections between nationalism, gender, and politics, or it can be read as a collection of essays on these themes. (Parts of three of the chapters had appeared earlier in edited volumes.) The book’s two parts focus on images of the nation, and the politics of women nationalists. It opens with the story of the official ceremony for the unveiling of Mahmud Mukhtar‘s monumental sculpture Nahdat Misr (The Awakening of Egypt) depicting Egypt as a woman. Baron draws attention to the paradox of the complete absence of women from a national ceremony celebrating a work in which woman represented the nation. For Baron, this incident is symbolic of the contradiction in the exclusion of the Egyptian women from the formal political sphere at a time when women occupied a central place in the images of the nation.

In Egypt as a Woman Beth Baron explores the connections between Egyptian nationalism, gendered images and discourses of the nation, and the politics of elite Egyptian women from the late nineteenth century to World War Two, focusing on the interwar period. Baron builds on earlier works on Egyptian nationalist and women’s history (especially Margot Badran‘s and her own) and draws on a wide array of primary sources such as newspapers, magazines, archival records, memoirs, literary sources such as ballads and plays, and visual sources such as cartoons, photographs, and monuments, as well as on the scholarship on nationalism, feminism, and gender. This book can be read as a monograph focused on the connections between nationalism, gender, and politics, or it can be read as a collection of essays on these themes. (Parts of three of the chapters had appeared earlier in edited volumes.) The book’s two parts focus on images of the nation, and the politics of women nationalists. It opens with the story of the official ceremony for the unveiling of Mahmud Mukhtar‘s monumental sculpture Nahdat Misr (The Awakening of Egypt) depicting Egypt as a woman. Baron draws attention to the paradox of the complete absence of women from a national ceremony celebrating a work in which woman represented the nation. For Baron, this incident is symbolic of the contradiction in the exclusion of the Egyptian women from the formal political sphere at a time when women occupied a central place in the images of the nation.

Chapter 1 provides the nineteenth-century background of the rise of the “Woman Question” in Egypt. Baron argues that the transformation of elite households in Egypt with the end of harem slavery marked the emergence of a new bourgeoisie. Nationalists used metaphors of the nation as a family in defining and drawing the ethnic boundaries of the nation and in promoting the ideal of the bourgeois family, a process that was already under way.  The “Woman Question” — debates about women’s education, work, marriage and divorce, seclusion and veiling — marked a cultural split between religious and secular nationalists, according to Baron. Secular nationalists, for example, viewed women’s segregation and the veil as symbols of backwardness that had to be fought. While elite women such as Huda Sharawi promoted unveiling as a liberating act in the post-independence era, as in women’s political rights, nationalist leaders did not commit themselves to women’s rights. It would be interesting to compare the stance of the Egyptian state in the interwar period to that of the Iranian and Turkish in the same period where the state took a more proactive role in the expansion of women’s rights.

The “Woman Question” — debates about women’s education, work, marriage and divorce, seclusion and veiling — marked a cultural split between religious and secular nationalists, according to Baron. Secular nationalists, for example, viewed women’s segregation and the veil as symbols of backwardness that had to be fought. While elite women such as Huda Sharawi promoted unveiling as a liberating act in the post-independence era, as in women’s political rights, nationalist leaders did not commit themselves to women’s rights. It would be interesting to compare the stance of the Egyptian state in the interwar period to that of the Iranian and Turkish in the same period where the state took a more proactive role in the expansion of women’s rights.

Chapter 2 discusses the appropriation of notions such as family honor in nationalist rhetoric. Baron tells that the concept of “national honor” developed in the context of resisting British control. Egypt was imagined as a family and as a woman, and national honor was linked with family honor, which depends on the conduct of its women. Baron shows that not only nationalists such as Mustafa Kamil appropriated the concept of honor in their speeches and proclamations, but the concept of national honor entered the popular culture through poems, plays, ballads, and songs. Nationalists referred to the incidents of rape of village women in 1919 by British soldiers as the rape of the nation. British occupation was an insult to national honor, hence Egyptians must fight to protect “faith, honour, and the homeland” (p. 42). Baron draws attention to the important differences in the language of male and female nationalists in discussions of national honor: In an effort to separate national honor from women’s sexuality, women nationalists, unlike their male counterparts, avoided the use of terms associated with female sexuality.

Chapter 3 turns to visual representations of the Egyptian nation in cartoons, pictures, posters, monuments, and sculptures, and state-produced media such as stamps. Nationalist images nearly universally depicted Egypt as a woman. Mahmud Mukhtar’s The Awakening of Egypt, for example, depicted a rising sphinx and a peasant woman unveiling. The recurrent image of the peasant woman in such depictions, Baron argues, celebrated Egyptian peasants as culturally authentic and emphasized their connection with the land. The recurring image of the peasant woman also places the Egyptian artists in the context of the peasantist ideologies and the cult of the peasant of the interwar years in Europe and parts of the Middle East.1 Baron notes that Egypt came to be depicted as a woman in nationalist images in a process that coincided with the unveiling of Egyptian women. She also notes that after 1923 the nation began to be depicted as the “new woman.” The new Egyptian woman was educated, well dressed, unveiled, traveled, and drove a car. Her image appears to have combined nationalist and modernist ideals of the Egyptian nationalists.2 Baron again draws attention to the contradiction that women were excluded from politics as nationalist images portrayed the nation as a woman.

Chapter 3 turns to visual representations of the Egyptian nation in cartoons, pictures, posters, monuments, and sculptures, and state-produced media such as stamps. Nationalist images nearly universally depicted Egypt as a woman. Mahmud Mukhtar’s The Awakening of Egypt, for example, depicted a rising sphinx and a peasant woman unveiling. The recurrent image of the peasant woman in such depictions, Baron argues, celebrated Egyptian peasants as culturally authentic and emphasized their connection with the land. The recurring image of the peasant woman also places the Egyptian artists in the context of the peasantist ideologies and the cult of the peasant of the interwar years in Europe and parts of the Middle East.1 Baron notes that Egypt came to be depicted as a woman in nationalist images in a process that coincided with the unveiling of Egyptian women. She also notes that after 1923 the nation began to be depicted as the “new woman.” The new Egyptian woman was educated, well dressed, unveiled, traveled, and drove a car. Her image appears to have combined nationalist and modernist ideals of the Egyptian nationalists.2 Baron again draws attention to the contradiction that women were excluded from politics as nationalist images portrayed the nation as a woman.

The final chapter in the first part, perhaps the most original and interesting part of the book, provides a brief history of photography in Egypt and discusses how photography, especially in the illustrated press, played an important role in the “construction and maintenance of a collective national memory” (p. 83). Drawing on Benedict Anderson’s notion of the nation as an “imagined community,” Baron maintains that photographs in the press helped with the imagination of an Egyptian nation. She examines who is included and who is excluded and how gender and class hierarchies are reflected in the photographs. There is an implicit assumption here that the illustrated press reached a significant part of Egyptian society and had an impact on the reader or the viewer. In addition to the lack of full and reliable circulation figures (and Baron does provide some estimates), it is hard to measure the actual impact of photographs in newspapers and magazines on the readers.

The second part of the book deals with the politics of the elite Egyptian women from 1919 into the 1940s. In the chapter on the “Ladies’ Demonstrations,” Baron analyzes the women’s demonstrations of March 1919 for the release of Sa’d Zaghlul and the other members of the Wafd as a site of Egyptian collective memory. Baron discusses how the women’s demonstrations became a part of the collective national memory through contemporary and later press coverage, photographs, literary works, memoirs, and commemorations of the 1919 revolution. Baron notes how the demonstrations were remembered and represented differently by women and men, and in contemporary and later nationalist coverage: men highlighted the symbolic importance of women’s demonstrations, while women emphasized the substantive contributions. While later representations claimed that women marched alongside men, these demonstrations were gender segregated. Baron shows that even though later nationalist representations downplayed class distinctions and portrayed the demonstrations as more popular and inclusive, these demonstrations reflected class hierarchies; they were demonstrations of elite Egyptian women wearing light face veils. Baron also notes that women’s demands in these demonstrations were nationalist demands made as mothers and sisters representing the women of the nation, not specifically women’s or feminist demands. Such participation, however, would provide justification for feminist calls for women’s equality: “women deserved rights because of the contributions they had made to the national cause” (p. 122).

The subsequent chapters focus on the lives and politics of individual women, including Safiyya Zaghlul, the wife of Wafdist nationalist leader Sa’d Zaghlul, four members of the Women’s Wafd (Huda Sharawi, Munira Thabit, Fatima al-Yusuf, and Esther Fahmi Wisa), and Islamic activist Labiba Ahmad. The author’s choice of these women was due to the availability of memoirs and other records of their lives such as contemporary press and archival accounts. Safiyya Zaghlul joined her husband Sa’d in the resistance against British rule, came to be known as the “Mother of the Egyptians” after 1919, and remained politically active during Sa’d Zaghlul’s nationalist leadership and after his death in 1927. Baron draws attention to both the liberating and the conservative aspects of Safiyya Zaghlul’s work. She argues that Safiyya Zaghlul served as a role model for nationalist women and the language of “mothers of the nation” helped her and others to create political roles for women, yet these roles were limited by the same language of motherhood that emphasized women’s reproductive and domestic roles, not their political roles, as primary.

The main argument of the chapter on the Wafdist women is that they were actively involved in the struggle for Egyptian independence through acts such as writing letters and petitions, boycotts of foreign goods, protests, marches, and demonstrations, but once independence was achieved these nationalist women were denied political rights. Baron argues that male nationalists tried to direct and control women’s activities at times of crisis such as 1919, but excluded them from normal politics, seeing women in supporting roles and not as political actors as such. She then demonstrates how politics came to be depicted as a male space in images such as cartoons of women activists in the interwar period. She further argues that the earlier efforts of male politicians as supporters of women’s rights were primarily intended to show the modernity of the nationalist women and therefore had greater impact on nationalist discourse than on legislation. Disillusioned with the formal politics of Egypt, women nationalists turned to other possibilities. Huda Sharawi, for example, resigned from the Women’s Wafd in 1924 and focused on social reforms through the Egyptian Feminist Union. Here Baron recognizes that politics is not limited to formal party and parliamentary politics, and can include activities in spheres such as journalism, feminism, education, and social welfare. This recognition is crucial in the attempt to restore women nationalists to Egyptian history, even though Baron in this book does not follow women activists in fields such as social welfare.

The discussion of the activism of Labiba Ahmad in the final chapter is especially interesting since she promoted the ideal of an Islamic Egypt and a modern Islamist woman while the majority of the elite Egyptian women held a secular vision of the nation and the modern woman. Labiba Ahmad propagated her ideas using all modern means available to activists, such as the print media, especially her own magazine al-Nahda al-Nisa’iyya (The Women’s Awakening), photography, associations, including social welfare organizations, and radio speeches. Baron argues that Labiba Ahmad’s Islamist ideology, while opening up some possibilities for women’s activism, ultimately narrowed women’s options and failed to pursue a radical social transformation. It would have been interesting to see how Labiba Ahmad’s ideas and acts informed Islamist women in the postwar era.

This book is successful in accomplishing its goal of incorporating elite women in nationalist politics of interwar Egypt. It does not, however, deal with the politics or culture of the majority of Egyptian women, or the impact of elite women’s activities on middle- and lower-class women and their perceptions of family, national identity, and politics. Hence while it contributes to a better understanding of Egyptian nationalism and Egyptian politics by including aspects of elite women’s politics, most middle-class, working, and peasant women, and the women of the royal family, remain outside the purview of this work. Baron suggests the politics of lower-class women would have to be studied separately in the post-1952 period. This could be taken to imply that working and peasant women did not participate in nationalist politics or that their histories can be recovered only after 1952, although presumably that is not what Baron intends.

One important area that Baron does not discuss, but recognizes as needing further research, is the relationship between nationalism and masculinity. Just as ideals about women’s and family honor influence ideas about the nation, ideals of masculinity play a role in shaping the nation and are in turn influenced by nationalist ideologies.3 The question of masculinity may also be relevant in explaining why male politicians shied away from recognizing women’s political rights in post-independence Egypt. Baron refers to the category of “male politicians” and mentions that as was common in post-colonial contexts male politicians denied women’s political rights once Egyptian independence was achieved. The category “male politicians” probably needs to be broken down. Were all male politicians of the interwar period against women’s emancipation? Were there important party, ideological, and individual differences among male politicians?

The question of why women were excluded from the political sphere after independence still needs further investigation. Baron continues a tradition of depicting a sharp break after independence. It is worth noting that recent scholarship, for example Lisa Pollard‘s book Nurturing the Nation: The Family Politics of Modernizing, Colonizing, and Liberating Egypt, 1805-1923, suggests a cultural continuity between the colonial and post-independence periods based on the ideas about the family, rather than the sharp break that Baron and others have depicted. Pollard argues that the exclusion of women from the political sphere after the 1919 revolution “represented the logical result of gendered debates about the Egyptian nation, national reform, and nationalism in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.”4 While Baron’s and Pollard’s conclusions are different, both accounts of women, family, and nationalism in Egypt are illuminating.

Scholars with an interest in connections between women, gender, and nationalist ideologies and politics would benefit from reading Egypt as a Woman. This book can also be assigned for graduate seminars or upper-division courses dealing with topics such as women and gender in the Middle East, women’s political culture, women and nationalism, secularism, women and the visual culture, and gender and historical memory.

Notes

1 On the cult of the peasant in interwar Turkey, see M.Asım Karaömerlioğlu, “The People’s Houses and the Cult of the Peasant in Turkey,” Middle Eastern Studies, 34 (1998): 67-91.

2 On the new woman in Turkey in the same time period see Sibel Bozdoğan, Modernism and Nation Building: Turkish Architectural Culture in the Early Republic (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001).

3 On Turkish nationalism, ideals of masculinity and the “military nation,” see Ayşe Gül Altınay’s The Myth of the Military Nation: Militarism, Gender, and Education in Turkey (London: Palgrave, 2005). Afsaneh Najmabadi explores the interplay of masculinity and nationalism in the Iranian case in her Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

4 Lisa Pollard, Nurturing the Nation: The Family Politics of Modernizing, Colonizing, and Liberating Egypt, 1805-1923 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 209.

Hale Yilmaz is Assistant Professor of History at Southern Illinois University. This review was published on H-Women (October 2008) under a Creative Commons 3.0 US License.

|

| Print