Sherry Wolf. Sexuality and Socialism: History, Politics, and Theory of LGBT Liberation. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2009. 333 pp. $12.

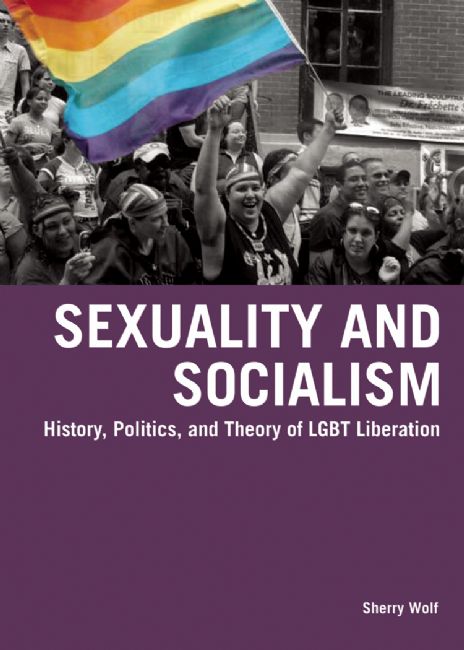

The cover photo on Sherry Wolf’s book shows a protest rally with a woman holding a highlighted rainbow flag. Radical gay and lesbian activists, one assumes. Look closely, though, and you’ll see that the woman is sporting a Hillary for President button. The contrast seems odd for a book on socialism. But maybe not. The idea that the Democratic Party can be pressured into doing the right thing for oppressed groups has grown stronger as the influence of the left has diminished. This mix of radicalism and reformism pervades the book.

The cover photo on Sherry Wolf’s book shows a protest rally with a woman holding a highlighted rainbow flag. Radical gay and lesbian activists, one assumes. Look closely, though, and you’ll see that the woman is sporting a Hillary for President button. The contrast seems odd for a book on socialism. But maybe not. The idea that the Democratic Party can be pressured into doing the right thing for oppressed groups has grown stronger as the influence of the left has diminished. This mix of radicalism and reformism pervades the book.

Wolf writes in a readable style, and her book offers a useful overview of the American gay movement’s history of the past few decades, as well as some insights into its politics. But despite the book’s strengths, it is riddled with errors and gives short shrift to the third element of her subtitle: theory.

A fundamental problem is her use of the LGBT acronym. As she notes, “desiring to be all-inclusive and readable” is a difficult task. To her credit, she rejects the “queer” label because of its negative historical baggage, but her decision to lump together “lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people” has its own problems. For one thing, there is no such thing as “LGBT people,” and it muddles differences of identity and oppression. I doubt there even is a “theory of LGBT liberation” — beyond, perhaps, asserting that all oppressed groups will be better off under socialism.

She begins with an examination of “the roots of LGBT oppression.” But here already she stumbles, and not only because of her alphabet soup of categories. “The oppression of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people has not always existed,” she writes, “and neither have LGBT people as a distinct sector of the population.” Indeed! But “LGBT” people (or “GLBT” or “LGBTQQIAA” or other bizarre acronyms) do not constitute a “distinct sector” today either, and she is wrong to trace the “oppression of all sexual minorities” solely to “modern capitalism.” The roots of sexual oppression in the West go back much earlier in class society. Homosexual oppression arose with the Holiness Code of Leviticus and is part of the Judeo-Christian tradition, compounded by the Anglo-Saxon legal heritage. Wolf ignores this history of the taboo on (male) homosexuality, or its relevance for today. (She doesn’t bother with cross-cultural or anthropological studies that might complicate her view.) She does recognize that it is “tied to” the nuclear family (a relatively recent institution) under capitalism, and says that “socialists fight for a world in which sexuality is a purely personal matter, without legal or material restrictions of any sort.”

But that last point is weakened by her failure to discuss the role that repression of youth sexuality (e.g., age-of-consent laws) plays in the repression of homosexual behavior. Wolf recycles bourgeois prejudice when it comes to intergenerational love, as her comments on nineteenth-century German labor leader Johann Baptiste von Schweitzer show. She refers to him as a “convicted pederast, as Engels called him — that is, a man who seduces boys.” But by inserting “seduction” into her novel definition of pederasty (a sexual relationship between a man and an adolescent youth), she repeats the foolish notion that a boy under the magical age of consent (whatever it happens to be) is by definition incapable of consenting to sex with a man: “Whatever the wrongs of age-of-consent legislation that carry over into the modern era [she mentions no ‘wrongs’], it should stand as a basic socialist principle that sex between two people must be consensual. It is incompatible for genuine consent devoid of the inequality of power to be given by a child to a man of thirty.”

But what is Wolf’s definition of a “child”? What does sexual freedom mean for youth? Did consensual sex with a teenager in nineteenth-century Germany merit punishment? Wolf fails to mention the more enlightened view of Schweitzer’s colleague, labor leader Ferdinand Lassalle, who said: “What Schweitzer did isn’t pretty, but I hardly look upon it as a crime. . . . In the long run, sexual activity is a matter of taste and ought to be left up to each person, so long as he doesn’t encroach upon someone else’s interests.” Wolf later notes that the Soviet criminal code of 1922 omitted mention of sodomy, incest, and age-of-consent laws: “‘Sexual maturity’ was to be determined on a case-by-case basis according to medical opinion.” So, does she favor abolishing age of consent in the law? Her failure to address such questions leaves in place the sexual status quo for young people. Her final chapter would have been more accurately titled “Sexual Liberation for Some!” (not “All”).

She regards the hot-button issues of the day — letting same-sexers serve openly in the military and gay marriage — as goals socialists should fight for. While she concedes that “hostility to the military is certainly understandable,” she thinks it is more important to critique the federal government’s “hiring practices,” even if the result is to strengthen the imperial military. She seems worried that “if LGBT people are eventually deemed qualified to kill or be killed for the empire, then other legal and social restrictions would only be amplified.” Her concerns already seem out of date. Top officials are pushing for repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell” because the policy hampers the war machine at a time when it needs all the bodies it can get. And, thanks to Obama (whose election Wolf considers a “victory” — for whom she doesn’t say), the Pentagon has the biggest war budget in history to pay for its aggression. Again, this seems like reformism posing as radicalism.

She describes at length the discrimination faced by same-sex couples (though not by transsexuals, whose interests hardly coincide with those of gays who want to get married since transsexuals already can), but has nothing to say about discrimination against singles, or about the many downsides of marriage (e.g., legal responsibility for a spouse’s credit card debts, or the messiness and expense of divorce and its often traumatic effects on any children involved). In an assertion that would have Frederick Engels turning over in his grave, she argues that marriage “is part of the class struggle.” Getting the state out of the marriage business and making marriage a purely private and/or religious affair would be a step toward genuine equality, but Wolf does not examine such an approach. She mentions civil unions only to denigrate them. She thinks her support for marriage is more radical than the critique of “queer theorists”: “in their opposition to civil rights struggles to ‘normalize’ and ‘assimilate’ LGBT people into wider society by fighting for reforms such as same-sex marriage or equal employment rights, queer theorists’ fundamental conservatism is exposed.” Isn’t this the pot calling the kettle black?

Her discussion of postmodernism (pp. 168ff.; not listed in the Index) is good, as is her critique of identity politics, as far as it goes. She is right to criticize the “sexual binary” in gay gene studies, and examines well the fluidity of same-sex practices and identity. She makes the cogent point that “Identity politics activists and scholars’ adherence to identity-based power blocs is tantamount to a rejection of the notion that class is a fundamental divide in society, thus they sever the link between exploitation and oppression.” And: “The legacy of identity politics organizing in the United States often lends itself to an unproductive ‘oppression Olympics’ [a neat term] in which different groups compete, in a sense, for which one is lowest on the totem pole. It seems a politically useless endeavor, as it only mirrors the ideological framework of the dominant class in whose interest these divisions persist.” But her own use of “LGBT people” is itself an example of politically correct identity politics, as is her taking of identity rather than sexual behavior as her starting point, and the reform agenda she supports has less to do with Marxism than with gay assimilation into the capitalist status quo.

Even her discussion of gay bashing focuses on identity, not on the fear of homosexuality that leads to it. Homoerotic attraction is universal, and the mostly young males who bash are acting out of fear of their own homoerotic impulses. But, with a “workerist” twist, Wolf sees this in terms of identity: “a minority of heterosexuals carry out acts of bigotry against LGBT people because, in addition to the competition under capitalism that exists between bosses for profits, there is competition among workers as well, for jobs, housing, education, etc.” Fear of homosexuality is reduced to fear of joblessness: “atomized and isolated, workers at times express their rage by turning against one another rather than the system and the class that exploits and oppresses them.” It’s unclear how this analysis would explain, say, the murder of Matthew Shepard.

The factual errors and instances of sloppy citation are too numerous to list, but here are a few:

Marx and Engels were not “socialism’s founders” (p. 9). The most detailed and free vision of sexuality under socialism was offered by the earlier utopian socialist Charles Fourier, whose Harmony provided for all varieties of sexual behavior, and whose writings on sexual freedom are far in advance of those of most Marxists. But Wolf does not mention Fourier.

Pederasts are defined as “homosexual pedophiles” (p. 77). Pederasts are men attracted to pubescent and postpubescent males; pedophiles are attracted to prepubescents. Here, Wolf is regurgitating bourgeois disiniformation.

U.S. leftist groups “defended Cuba’s earlier record of abuse against sexual minorities or simply ignored it” (p. 106). This distortion seems designed to show Wolf’s International Socialist Organization (ISO) in a favorable light compared to other leftist groups. While it is true that Maoists and the Communist Party are guilty as charged, the blanket statement is false. I myself gave a forum in New York for the Socialist Workers Party in the early 1970s (reported in the Village Voice) condemning the Cuban persecution of Heberto Padilla and the 1971 Cuban Cultural Congress’s condemnation of homosexuality as a “social pathology,” as well as the internment of homosexuals in the 1960s.

The internal debates in the SWP on gay liberation lasted nine years (1970–79), not three (p. 108).

Homosexuality per se was never outlawed in the United States (p. 117); only certain acts were illegal.

GAA’s name was Gay Activists (not Activist) Alliance (pp. 129, 142, 325).

Neither edition of Donn Teal’s The Gay Militants (she omits The from the title) says that the SWP was perceived by the Gay Liberation Front to be “notorious Puritans” (the quote, from Bob Martin of the youth committee of NACHO, not GLF, says nothing about the SWP: “Revolutionaries are notorious Puritans and so many radicals are uptight about their own sexual orientation”), nor were Maoists the “dominant leftist influence” in the GLF (p. 132).

The Red Butterfly cell was not formed by “Maoist gays” (p. 136).

She discusses how radical lesbians challenged NOW’s early hostility to lesbianism (p. 136), but fails to mention the notorious antigay, antimale resolution adopted at NOW’s October 1980 convention at the behest of its Lesbian Rights Committee, and never rescinded, condemning pederasty, public sex, sadomasochism, prostitution, and pornography.

GRID stood for Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, not “Gay-Related Infectious Disease” (pp. 164, 326).

Mattachine was not the first U.S. gay organization (p. 244).

The IWW was the Industrial (not International) Workers of the World (p. 244).

There are also numerous errors in the identification of sources in the notes. In some cases, the author given is wrong; I was the editor of Gay Liberation and Socialism, for example, not Forgione and Hill (pp. 292, 295), and 300 (not 20) copies were published, as is clearly stated in the copy she says was lent to her by David Whitehouse (who bought his copy from me).

Wolf often cites as her source books by supporters of the ISO (which published her book and to which she belongs) when the information originally appeared elsewhere (e.g., in John Lauritsen’s and my The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864–1935)). This happens enough to suggest that it is intentional.

The book’s architecture is sloppy. Frequently, the first time a work is cited, only a short title and the author’s last name are given, so complete publication information is not provided anywhere.

The “Selected Readings” is not alphabetized; works are listed haphazardly.

At 5 X 7 inches, Wolf’s book is compact and easy to hold. But despite her good intentions, and her excellent, if sometimes cursory, treatment of subjects like postmodernism and poststructuralism, Foucault, identity politics, and “queer,” her book is not always a reliable guide to history, and fails to make a convincing case for socialism as the way forward for sexual minorities.

David Thorstad is a co-author of The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864-1935), the editor of Gay Liberation and Socialism: Documents from the Discussions on Gay Liberation Inside the Socialist Workers Party (1970-1973), and the translator of Maxime Rodinson’s Israel: A Colonial-Settler State? among other works he has published. Thorstad also makes an appearance in Guy Hocquenghem’s Le gay voyage: guide et regard homosexuels sur les grandes métropoles.

|

| Print