For years, right-wing groups have been beating the drums to roll back decent pensions and retirement benefits for American workers. At the federal level, Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan, ranking member on the U.S. House Budget Committee, proposed a “Road Map” plan to privatize social security, cut payments, and slash Medicare benefits for all seniors.

Similarly, state-based conservative groups like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) have called for cutting public employee pension and health care benefits and replacing them with less secure 401k-style plans that would inevitably leave many retirees in poverty.

Yet despite these attacks and in the midst of financial meltdowns in the private sector, state public pensions are largely a success story, riding out the economic storm, delivering benefits to families, helping drive economic demand in state economies, and projecting solvency for decades to come.

Don’t Believe the Hype: It’s unfortunate that a report from the Pew Center on the States added to right-wing doomsaying about state retirement systems with its alarmist title, The Trillion Dollar Gap: Underfunded State Retirement Systems and the Road to Reform. In fact, the actual substance of the report paints a pretty positive story about fiscal responsibility by most states and highlights well-funded pensions with trillions of dollars in assets available to deliver benefits in coming decades.

As this Dispatch will emphasize, there is no crisis in most state retirement systems, even according to the numbers of the researchers demanding state leaders take unneeded action to cut the incomes of retirees. And despite the hype from a few carefully selected anecdotes of retirees gaming pension systems, the reality is that the overwhelming number of public employees receive pretty bare-bones benefits, in some cases not enough even to keep them out of poverty.

We do need a debate on public pensions, but one that sees protecting them as part of a broader campaign to restore retirement security for all American workers, especially in the wake of a stock market collapse that has revealed the empty promises of Wall Street in hyping 401k-style private accounts as a substitute for the guaranteed retirement income of social security and defined-benefit pensions. Public pensions are actually a key tool for driving economic growth in the states, both through the purchasing power of retirees themselves and through the direct investments of pension assets in job creation. Any reforms undertaken should be done to both enhance the positive economic role of retirement systems in our state economies and to increase equity among retirees to raise living standards for low-income retirees.

The Non-Existent Public Pension Funding Crisis

When budgets are tight, stories about underfunded state retiree benefits make for good newspaper stories, but the details of the Pew study — if you ignore their press release — is actually a compendium of good news:

- State employee pension plans are providing reliable post-employment income to millions of working Americans.

- States have put away $2.35 trillion in assets in dedicated investment funds to cover expected costs for those benefits over coming decades.

- According to best actuarial practices, aggregate state pension funds are 84% funded for expected expenses over the next thirty years, which is actually more than the 80% level recommended by most experts, including the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

As the Government Accountability Office wrote last year in a similar report:

[M]ost state and local government pension plans have enough invested resources set aside to pay for the benefits they are scheduled to pay over the next several decades . . . pension benefits are generally not at risk in the near term because current assets and new contributions may be sufficient to pay benefits for several years.

While at the end of fiscal year 2008, 21 states had funding levels below the 80 percent mark, some states below this mark will need to make adjustments to current defined benefit plans and can address those issues and states have time to craft changes that will avoid unintended consequences and achieve long term plan viability. The report does note reason for concerns with regards to pre-funding retiree health benefit costs. However, unlike pension benefits, governments have the option to pre-fund health care or continue to pay as you go. As we all know, the challenge on all forms of health care costs has more to do with finding comprehensive solutions in health care.

Debunking the Crisis Rhetoric: The Pew study trades in the dauntingly large numbers involved in public pensions to create its headline-chasing hype out of all this good news.

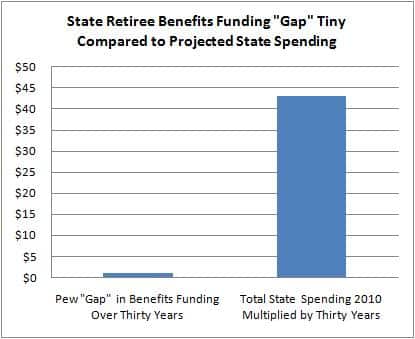

Adding up projected costs for pensions and health care benefits, Pew calculates a thirty-year $1 trillion shortfall, but, when compared to total spending by states over the next thirty years, that $1 trillion “gap” projected by Pew is statistical noise likely to be dwarfed by all the other forces shaping state budgets. As the graph at the right indicates, if you just multiply total state spending projected for fiscal year 2010 — roughly $1.5 trillion — by the projected thirty years, the retiree benefits “gap” is tiny. And this overall state spending projection is highly conservative, since it ignores likely spending and revenue increases due to population and per capita income growth.

Retiree Benefit Costs Mostly Not Paid by Current Taxpayers: To heighten the sense of taxpayer anxiety over retiree benefits, Pew argues that its own hyped $1 trillion gap “amounts to more than $8,800 for every household in the United States.” The problem is that even that $8,800 number, divided by thirty years, amounts to only $300 per year. Since employees already themselves pay for 40 percent of the pre-investment contributions made to cover their retirement and investment income covers much of the rest, taxpaying households would be expected to pay something on the order of 25% of the $300 per year — or roughly $75 — to cover the retirement costs of teachers, nurses and other state employees. This is just a projected cost and may never come to pass in any case.

To put this non-crisis in perspective, the Government Accountability Office said last summer, “our analysis shows that state and local governments on average would need to increase pension contribution rates to 9.3 percent of salaries — less than .5 percent more than the 9.0 percent contribution rate in 2006 to achieve healthy funding on an ongoing basis.” Divided between employees and employers in whatever way negotiated, this is hardly an earth-shaking departure from the status quo.

To put these numbers in further perspective, back in the 1990s states had such strong investment returns and pension assets shot up so dramatically that many pension funds were over-funded (Pew 24). So when the current economic crisis passes, it is quite possible that the current hype about underfunding will just yield over-funded retiree funds.

Overall, Pew’s and other groups’ attempts to inflame the issue of pre-funding retiree benefits is not helpful. States are already mostly doing a good job on pre-funding pension obligations and have made inroads in pre-funding non-pension obligations such as retiree health benefits. The amounts needed to fund obligations may be large but can be set aside over time.

Most Public Employees Do Not Have Generous Retirement Benefits

Instead of using the hype around supposed underfunded retiree benefits to justify cutting pension income and health care for retirees, states should instead be discussing whether the modest pensions retirees do receive are enough to retain a strong workforce for our schools, public hospitals, and other public institutions going into the future.

The basic numbers show that public pensions provide solid, but hardly overly generous support to most retirees and leave many retirees in need due to the low levels of support they receive. In fiscal year 2006, the last year for which the U.S. Government Accountability Office had full information, state and local government pension systems covered 18.4 million members and made periodic payments to 7.3 million beneficiaries, paying out $151.7 billion in benefits. That comes out to $20,780 per beneficiary per year. While modest, as the National Institute on Retirement Security has documented, defined benefit plans are key factors in many families in reducing the risk of poverty among the elderly.

Even those modest amounts were covered largely through investment returns, with public employees themselves contributing an average of 40 percent of non-investment contributions to their own retirement (Pew 10). In a number of states, public employees don’t even qualify for social security, so funding pensions in those states or occupations is not a supplement to federal retirement benefits, but a complete substitute.

A few examples of retiree pension benefits from around the country:

- California has the largest pension system in the country with 492,513 retirees receiving average monthly benefits of $2,101 ($25,212 annually) from the CalPERS system based on an average of 20.1 years of service.

- Illinois: The average monthly benefit for current year retirees in Illinois was $2,574.36 ($30,888 per year) with average service of 25.4 years. Most employee groups pay 8% or more of their salary into the system. Those receiving social security receive less than that average — $1,868.68 per month in the main State Employee Retirement Service (SERS).

- Iowa: In fiscal year 2009, 89,847 retirees received an average monthly payment of $1,064 per month. Even those with more than 30 years of service received only an average of $2,071 per month. Current state employees paid $271 million out of their own paychecks (compared to $451 million by Iowa governments) for support of the system.

- Louisiana: Notably, Louisiana public employees don’t receive social security, so the average annual benefit they receive of $19,552 is often all they have to live on. Because of this, the Baton Rouge Advocate detailed in 2008 that many retired state employees live in poverty after decades of full-time work for the state.

According to AFSCME, the union which represents many state and local employees across the country, the average annual benefit for their retired members is $18,000 per year, which is a small gain from seven years ago, when the median annual benefit was $13,000 according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute.

A Few Anecdotes Don’t Represent the Real Story on Retiree Benefits: While the media often focuses on the tiny minority of public employees who game the system to receive the occasionally outrageous benefits — although usually nothing compared to extreme private sector bonuses and retirement packages — those examples are exceptions and not representative of the norm. For example, the Orange County Register identified 24 retirees in the state that received benefits in excess of $200,000 per year, but they also noted that over half of retirees received $15,948 per year or less. As the Register noted, it’s often just a handful of managers or a few other employees abusing the system that spike the overall dollar numbers, giving a false impression of the benefits available to most public employees in retirement.

The biggest mistake for policymakers would be to cut benefits for all retirees in response to news stories about a few outliers exploiting the system. In fact, such inequities for high-paid retirees may be statistically disguising the fact that other employees are receiving too meager retirement benefits; state leaders should consider raising the pensions of low-paid retirees even as they stop the abuses by others.

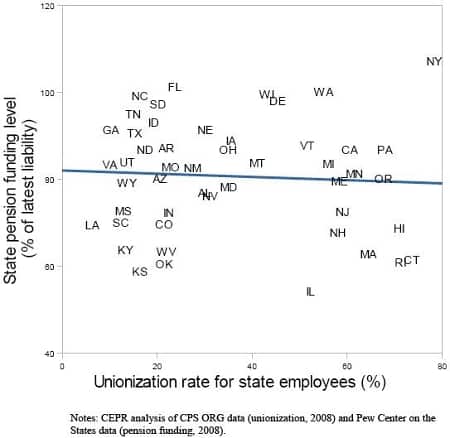

Public Employee Unions Are Not Driving Underfunding of Retiree Benefits: Part of the rhetoric around high-paid retirees and the supposed public pension crisis is blaming public employee unions for pushing states into fiscal crisis. Yet as the graph below indicates, courtesy of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, there is zero correlation between the degree of state employee unionization and how well funded state plans are.

In fact, New York state has the highest unionization rate in the country and the highest funding level compared to its liability of any state, while other high unionization states like Connecticut and Rhode Island share honors with low-unionization states like Kansas and Louisiana for falling somewhat below the 80% goal for pre-funding retiree obligations. What’s clear is that budgetary factors quite unrelated to the level of public employee unionization are the main factors in how well states pre-fund their pension obligations.

Seeking equity in retiree benefits: Since public employees in most states make significant individual contributions to pre-funded pension systems, the real focus for state leaders should be ensuring that equity is achieved among retirees and that all retirees receive the income and support they need when they do retire. Policymakers should consider overall plan funding and sustainability, not across-the-board benefits cuts for future workers, in seeking to strengthen retirement systems for all retiring workers.

Pension Systems Are Engines of Economic Growth

Beyond helping public employees themselves, policymakers should understand that pension and other retiree benefit programs are key engines for driving job creation in their states, both through direct spending on behalf of retirees and through pension fund investments in local businesses. Instead of the narrow focus based on fiscal fears and benefits cuts recommended by Pew and others, state leaders should step back to better understand how to enhance the positive economic role retirement systems play in their state economies.

State Governments Are Neither Households Nor Regular Employers: A common mistake in discussing state budgets is to discuss them with analogies to household budgets or to compare the government to private employers. But there is a crucial difference — states spend money, but they also collect revenues based on the economic activity generated by their spending. When households or private employers spend money, the money is gone. But when a state spends money, at least part of the money goes to purchases on which the state collects sales taxes or property taxes, while the people or companies receiving the funds in turn generate more economic activity. And part of that economic activity returns to the state in the form of taxes that can, in turn, be reinvested to promote more economic activity.

For example, states spend money on the education of children partly in order to promote future economic growth that will in turn yield the tax revenue that will fund the retirement costs of future retirees. Spending by those retirees will go to hospitals, restaurants, and a range of other services that will employ the adults those children will have become. So pensions are never simple “costs” but are part of a broad economic system that sustains whole communities over time.

Direct Effect of Pension Spending in States: The National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS) recently found that the benefits provided by state and local government pension plans have a significant economic footprint: 2.5 million American jobs and $358 billion in economic impact. As the study notes, public employee pensions are key economic drivers in many communities:

The steady, monthly benefit payments offered by public pension plans provide peace of mind and security for retirees, but local economies, in turn, benefit from the regular expenditures these retirees make on food, medical services, transportation, and even the occasional movie matinee. Public pension payments are vital to small communities and economies across the country where, due to lack of diverse local industries, other steady sources of income may not be readily found.

For each dollar paid out in pension benefits, $2.36 in total economic output was supported. Since taxpayer contributions are only a small part of funding for pensions, with investment earnings and employee contributions financing most of the benefits, the taxpayer dollars that are invested actually yield $11.45 in total economic output due to pension benefits for every $1 of taxpayer funding. It’s hard to identify any public investment that leverages similar economic growth multipliers.

To put the costs of funding any “gap” in retiree benefits in perspective, NIRS estimates that pension spending by retirees generates $21.2 billion in state and local taxes annually — with the federal government receiving $29 billion in federal tax revenues due to public employee pension spending.

Download fifty state fact sheets on the economic impact of state and local pension plans here.

Pension Investments Support Local Job Creation: The NIRS report only looked at the economic impact of the pensions directly paid to retirees, but pension funds also creatively use the investment money they hold to promote job creation in states across the country. As we described last month in the first of our State Job Creation Strategies series, states are increasingly using state pension fund investment dollars to provide capital for local job creation and business start-ups.

One study found that the California Public Employees’ Retirement System’s in-state investments fed an estimated $15.1 billion into in-state economic activity in 2006 and created 124,000 jobs — more jobs than the construction or motion picture industries. Florida recently redirected $1.95 billion of the state’s pension fund into direct investments in Florida’s economy, while Indiana’s public pension funds collaborated with state universities and various health-based companies to launch the Indiana Future Fund to support Indiana companies, especially in the life sciences and high technology arena.

Given the erratic investment patterns of the traditional banking industry, the $2 trillion plus in state pension funds may be an increasingly important source of capital for such local businesses.

References

CalPERS. “CalPERS – An Economic Engine.”

National Institute on Retirement Security. “50 State Fact Sheets.”

—–. “Pensionomics: Measuring the Economic Impact of State & Local Pension Plans.”

—–. “The Pension Factor: Assessing the Role of DB Plans in Reducing Elder Hardships.”

Pew Center on the States. “The Trillion Dollar Gap: Underfunded State Retirement Systems and the Road to Reform.”

Progressive States Network. “State Job Creation Strategies Part I: Finding the Money and Investing in Human Capital and Physical Infrastructure.”

U.S. Government Accountability Office. “State and Local Government Retiree Benefits: Current Funded Status of Pension and Health Benefits.”

Nathan Newman is Executive Director of the Progressive States Network. The article above is adapted from a Dispatch published by The Progressive States Network on 22 February 2010 for non-profit educational purposes.

|

| Print