Squaw Point today (photo by David Thorstad)  Silent City (photo by David Thorstad) |

In 1904, the Ojibwe village at Thief River Falls, in northwest Minnesota, was removed to the Red Lake Indian Reservation to the east, much diminished after the tribe’s cession of 256,152 acres between the reservation and Thief River Falls (known as the eleven western townships). The Indian cemetery at the village, on a piece of land known as “Squaw Point,” where the Red Lake and Thief rivers meet, was dug up and around 115 remains were taken by barge up the Red Lake River where they were to be “buried at a suitable point on the banks of the Red Lake river just across the reservation line.”1 Red Laker Wub-e-ke-niew, in his book We Have the Right to Exist, says “the Métis told us that our dead were dumped near where the old Frogs’ Bridge was, but I went and looked, and found no evidence of this.” Two issues were involved in the removal, he says: “one of them was the plundering of the graves of my people for ‘artifacts,’ the second was the removal of all physical evidence that the Ahnishinahbæótjibway had ever lived in the area.”2

This site is known at Red Lake as Silent City. It is hard to imagine that anything could have been reburied in this marshy terrain, even as it is today. It is possible that the barge could not proceed any farther than Frogs’ Bridge, so had to leave the dead there. Another version from Red Lake has tribal elders stopping the barge out of disagreement with the village band, whose chief, Red Robe, had accepted allotment, whereas Red Lake had rejected allotment in favor of keeping all land to be owned in common by the tribe as a whole. This scenario seems unlikely because the village Indians “said they were willing to remove at any time, but would not sign any paper until their head men up at the lake approved of the matter.”3 The story of Silent City remains sensitive for Red Lake, and may be fraught with superstition as well. When I mentioned my research to one tribal official, he replied: “Some things should not be written about.”4

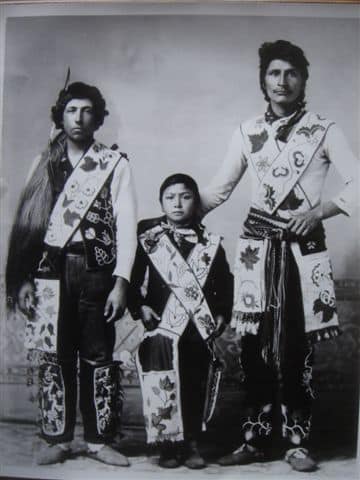

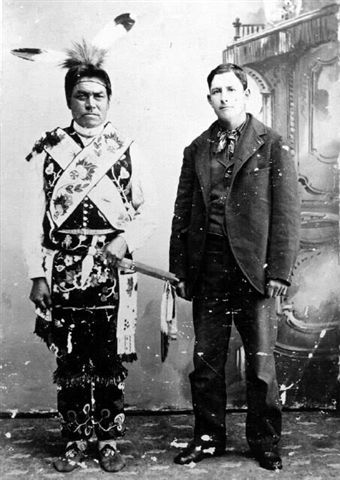

Rudolph Berg (left) with John Strong (a son of Red Robe) and grandson (photo by Smith). Berg was the interpreter when the Ojibwe cemetery at Squaw Point was moved to the Red Lake reservation in 1904. |

Bidding was taken for the removal of the cemetery, and the contract was awarded to Joseph Duchamp, who got $14.50 per body (it is possible that bones were not always kept together, so that more remains could be claimed to have been dug up). The remains were transported on a barge towed by the gas boat the Dan Patch. The translator for the operation was Rudolph Berg, a young Norwegian who left his family at age thirteen to live with the Red Lake Indians in the late nineteenth century. On June 20, 1904, sales of the ceded land began, most going for four to five dollars an acre.5

The Ojibwe village, known as Negiddahmitigwayyung, “Where the Two Rivers Meet,” was located across the river from a tract of 640 acres that Red Robe had inherited when his father Mons-o-moh (Moose Dung) died in 1872. Whites had given Moose Dung the tract, known as the “Chief’s Section,” in gratitude for his help in persuading his fellow Red Lakers to sign the 1863 Old Crossing Treaty ceding 11 million acres of the most fertile land in the country along the valley of the Red River of the North.

Moose Dung’s Role at Old Crossing

Moozomo (Moose Dung), possibly Red Robe’s father; photo taken “before 1877” |

Of the Red Lake delegation to the negotiations at Old Crossing in October 1863, only one chief refused to sign the treaty: May-dwa-gun-on-ind. He left the negotiations after several days and later hiked the hundred or so miles from Red Lake to White Earth to beseech Episcopal Bishop Henry Whipple to intercede on behalf of the Indians with Washington. Whipple had described this leading chief from Red Lake as “six feet and four inches in height, straight as an arrow, with flashing eyes, frank, open countenance, and as dignified in bearing as one of a kingly race.”6 The government’s negotiator, former Minnesota governor Alexander Ramsey, described this chief and Moose Dung in his report to William P. Dole, Commissioner of Indian Affairs: “It here should be explained that Moose Dung, who was really the most influential of all the chiefs, stood at the head of a party embracing the large majority of all the bands who were favorable to and even anxious for a treaty, while May-dwa-gun-on-ind led a small and surly minority, who were determined, for reasons of their own, that no treaty should be made.” Once May-dwa-gun-on-ind had left, Moose Dung’s role in the negotiations increased, ultimately helping to persuade the delegation to sign the treaty. For that he was rewarded with the 640 acres. It is easy to see why if his comments as recorded by Ramsey are correct, for they come across as more ingratiating than a mere negotiating stance might have called for. Moose Dung kept insisting that he wanted the tract of land including the mouth of the Thief River, but Ramsey replied: “Tell him I don’t care anything about the mouth of Thieving river. He can have it if he wants it.” Ramsey acts as if he is giving land to an Indian whose land it already is!

One by one, the Red Lake chiefs were won over to Moose Dung’s more conciliatory position. Ramsey made his final offer, including annuity payments, money for building houses for the chiefs, various goods, and so on, as well as a ban on liquor in the ceded land, to which Moose Dung responded:

Father, you have hit my heart in the right spot, in speaking of the liquor as you did. That is what I don’t want in my land, because it is the source of trouble and poverty. Father, I accept of the propositions, because I see that I am going to be raised from want to riches, to be raised to the level of the white man. Father, I hope you will do what is right with me, and my young men. I have always found that in holding in, I sometimes get more from my traders. You and the government have used every exertion for a great many years to bring about a treaty; I do not want you to exert yourself in vain; I now give up the tract of country; I hope you will have pity on me, and see that these terms are carried out to the letter, so as not to lead to trouble hereafter.7

After an hour of deliberating over each provision of the treaty, Moose Dung “touched the pen.” There was “great rejoicing in the Indian camp.”

By 1891, Red Robe had begun to lease out or sell parcels of the land he had inherited, mostly to lumbermen, and by 1901 he had lost all of it, so many whites saw no need for Indians to be living there and were glad to see them go in 1904 — a sad, even ignominious, end to the brief history of the only parcel of Red Lake land taken as an allotment by a leading member of the tribe.

The entire treaty period was a land grab, and the whites used various stratagems to get their hands on Indian land, including naming pliable men “chiefs” who then became professional treaty signers. As happened with other tribes, the Ojibwe were browbeaten, threatened, lied to, cajoled, and hoodwinked out of most of their land. As the main Red River Valley daily observed about the Old Crossing Treaty:

When this treaty was negotiated, the Chippewa Indian leaders were conned into turning over 11 million acres of prime real estate in Northwestern Minnesota and Northeastern North Dakota for about half a million dollars. As far as real estate deals go, the ceding of the Red River Valley ranks up there with the Manhattan deal, the Louisiana Purchase, and the Alaska deal. It has been characterized as one of the most dishonest and fraudulent deals ever made.8

A Generic Indian

Moose Dung (Mons-o-mo) and his son Red Robe (Mis-co-co-noy-a) both signed the Old Crossing Treaty, the former as a chief, the latter as a warrior. When Moose Dung died in 1872, Red Robe took his father’s name, and became known as both Red Robe and Moose Dung the Younger. This practice was not uncommon among the Ojibwe.

For the U.S. Bicentennial in 1976, the Thief River Falls authorities decided to have a statue built of an Indian chief overlooking the site of the original Ojibwe village. The chief the statue portrayed was identified as Moose Dung in the plaque, which read as follows:

At the Old Crossing Treaty of 1863 Provision was made for 640 acres of land near the mouth of the Thief River to be given to the Chief of the Red Lake Band of the Chippewa Indians.

The Chief’s Section, on which a big part of Thief River Falls is located was inherited by Chief Mon-si-moh (also known as Chief Red Robe). In 1879 following a government survey, Mon-si-moh decided the land was too valuable to lie idle and for several years dealt with lumbermen leasing land to them. In 1895 the first sale was made from the Chief’s Section. By 1901 he had sold the last of his holdings.9

This failed to make clear that the parcel of land that became known as the Chief’s Section was originally given to Red Robe’s father, Moose Dung, and makes no mention of the son’s original Indian name, Mis-co-co-noy-a. It also elides aspects of the story that would not make city officials, especially local lumbermen, look very good, since, as soon as whites began to move into the area and it was platted, lumbermen sought to acquire it, which they did, piece by piece. The Thief River Falls newspaper at the time was owned by Patrick and James Meehan, who built their lumber mill in the young town in 1892 and were among those who ultimately gained possession of Red Robe’s land, so newspaper coverage was biased in favor of the lumber interests.10

The most confusing — and surprising — thing about the statue is that it doesn’t look at all like Red Robe. It was clearly based on a photograph of Red Robe from 1885 because the statue’s clothing is identical to what the chief was wearing in the photograph, including his bandolier bag, the club he is holding, and the two eagle feathers in his hair. And it did not resemble the only photograph of a Moose Dung (Moozomo) I have seen, on the Red Lake Web site. (The photo was taken “before 1877,” and since Moose Dung the Elder died in 1872, it seems likely — even if impossible to confirm — that it is of Red Robe’s father.) One might reasonably have expected the statue to have been of Moose Dung the Elder, since he was the original grantee, though by the time Thief River Falls was being settled, the father had died, so the son became most closely identified with the tract in the eyes of whites.

Red Robe statue in Red Robe Park, Thief River Falls (photo by David Thorstad) |

Red Robe (left) and Albert Stately, 1885 (photo from Minnesota Historical Society) |

Thief River Falls businessman L. B. Hartz headed a committee that paid between seven and ten thousand dollars for the statue as part of the city’s commemoration of the Bicentennial. The statue was built by Creative Display, Inc., of Sparta, Wisconsin (later, the FAST Corporation). The craftsman who designed it was Jerry Vettrus, who confirms that he worked from the photograph of Red Robe taken in 1885 but says that it would have cost around a thousand dollars extra to have made the face look like the chief.11 Rick Contos, cochair of the Bicentennial commission, recalls: “I did not have any input after we had (we thought) the proper photo/I.D. for the statue’s appearance; L. B. and his committee members took it from there, the financing, etc. was entirely the prerogative of the Statue/Park committee.” Contos says that when the commission was dissolved, “we were literally broke financially.”12 For some reason, Hartz or others did not wish to spend the extra money to make the statue authentic, so instead Vettrus designed one that kept only the clothing Red Robe was wearing in the photograph. The result was a generic Indian.

It is hard to imagine anyone commissioning a generic statue of an important white figure — say, George Washington — that doesn’t even vaguely look like him. This slight has resulted in the fact that there are at least four other statues made from the same mold in other parts of the United States: at the Loretta Lynn Dude Ranch in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee; a Big Indian Statue at the Dixie Discount in Franklin, Kentucky; a “Southern Plains Indian” at the Cherokee Inn in Geary, Oklahoma; and another at the Navajo Travel Lodge in Gallup, New Mexico. All of these statues have the exact same face as the Red Robe statue in Thief River Falls, are holding a “tomahawk” in the same position as he does, and have a similar bandolier bag, though other details, such as feathers and designs on the bandolier bag, differ in minor ways.13

Red Robe’s grandson, Joe K. Sumner, told the Thief River Falls Times in 1976 — after the statue had been erected — that he would prefer to have his grandfather remembered as Red Robe rather than as Moose Dung, which he said was a nickname given him as a boy.14 Red Laker Dan Needham too told the crowd at the statue’s dedication that Moose Dung “was a nick-name given the chief by other Indians.”15 Mons-o-moh might have been a nickname, but it was not given to Red Robe, but to his father.

The Statue Gets Renamed

By 1997, the statue needed a new coat of paint, so the Parks and Recreation Board decided to revise the plaque as well, in deference to the wishes of Red Lakers who argued that the plaque was inaccurate by identifying Red Robe as Moose Dung.16 The new plaque text removed any mention of Moose Dung and asserted that both father and son were named Red Robe:

At the Old Crossing Treaty of 1863, a provision was made for the retention of 640 acres of land near the mouth of the Thief River by a chief of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa. The Chief Meskokonaye (Red Robe) section, on which a large part of Thief River Falls is located, was inherited by his son, who was also known as Meskokonaye.

In 1879, following a government survey, the chief’s son was coerced into leasing land to lumbermen. In 1895, the first sale of land was made from the chief’s section.

By 1901, Meskokonaye had been forced to part with the last of his holdings.17

This version is an improvement over the original plaque, but there are several inaccuracies, including the fact that there is no documentary evidence that Moose Dung the Elder was ever known as Red Robe. When Red Robe took his father’s name after his father died in 1872, he became known by both names.

Was Moose Dung Really Red Robe?

The origin of the notion that both Moose Dung and Red Robe were known as Red Robe appears to go back to the book Mary Croteau wrote for the seventy-fifth anniversary of Thief River Falls in 1971: Where Two Rivers Meet: A Diamond Jubilee History of Thief River Falls. Unfortunately, her account is inaccurate, garbled, and lacks any sources, and she is now dead. The book was republished for the city’s centennial in 1996, and Croteau’s errors were compounded. Here is what she wrote in 1971:

In 1863 the Red Lake and Pembina Chippewa and the federal government concluded a Treaty that opened up a large tract of land to homesteaders. This treaty was amended in 1864 when Chief Moose Dung, the elder (Mis-co-co-noy) and Chief Red Bear (Mis-co-muk-wa) of the Pembina Chippewa sent a delegation to Washington. . . . As a reward from the government for his work in arranging the treaty Chief Moose Dung, at his request, was given the site at the headwaters of the Thief River for his Indians.18

There are two glaring errors in this passage: first, she confuses Moose Dung with his son by giving Red Robe’s Ojibwe name (“Mis-co-co-noy”) as that of his father (the elder man was Mon-si-moh, not Mis-co-co-noy); second, the land Moose Dung was given was not at the headwaters of the Thief River, but at its mouth, the point where the Thief River and the Red Lake River meet.

The same passage in the 1996 version of the book compounds the first error and reads as follows:

In 1863 the Red Lake and Pembina Chippewa and the Federal Government concluded a Treaty that opened up a large tract of land to homesteaders. This treaty was amended in 1864 when Chief Miscoconoy, the elder and chief Red Bear (Mis-co-muk-wa) of the Pembina Chippewa sent a delegation to Washington. . . . As a reward from the government for his work in arranging the treaty Chief Miscoconoy, at his request, was given the site at the headwaters of the Thief River for his Indians. (2)

Here, Moose Dung has been erased altogether and history altered so that it was Red Robe who was given what became known as the Chief’s Section.

The confusion has persisted on the present-day plaque on the Red Robe statue, where both father and son are named Meskokonaye (Red Robe), but the fact that Red Robe assumed his father’s name, Monsomoh, when his father died would alone appear to refute that.

Names in Ojibwe tradition were not a simple matter of being given one at birth and retaining it for life. There were different kinds of names, and they could be bestowed on either an infant or an adult. Frances Densmore, in Chippewa Customs, lists six types: a dream name given by a “namer”; a dream name taken by an individual; a “namesake name” given by a parent; a common name or “nickname”; name of gens; and “euphonious name without any significance.”19 A person might also use a particular name to ward off bad medicine. Sometimes children were not named until they fell sick, whereupon a namer would be summoned in the belief that his naming power could save the child’s life.

Densmore’s description of the nickname would appear to apply to Moose Dung the Elder:

The common name or nickname was that by which a Chippewa was known throughout his life. It was short and frequently contained an element of humor. A child might be given a name derived from some circumstance at the time of its birth, or it might be named from the first person or animal that entered the lodge after its birth. Children were sometimes named from a fancied resemblance to something. . . . The element of humor is shown in the fact that a child who was a long time in teething received the name Without Teeth, and a child who was short in stature was named Stump, both names being carried by men who lived to an advanced age.20

Red Lake elder Tom Lussier explained the importance of having an Indian name:

I’ve got an Indian name. Most of the family has their Indian names. There’s a lot of belief in that, too. That if you don’t have your Indian name when you go to the happy hunting ground, then you’ll be like in a limbo or a purgatory. The white heaven don’t recognize you, and you can’t get into the Indian place because you don’t have your name. You can’t tell them who you are, when you get there. If you don’t have your Indian name, you’ll be floating in the never-never land forever.21

Some people think Moose Dung is a pejorative name: Why would anyone want to be named for animal droppings? “I was always under the assumption that the statue was renamed as the name Moose Dung may have been termed derogatory and that is why it was changed,” says former Red Lake Tribal Chairman Bobby Whitefeather.22 That is a common, but ill-informed, assumption made by many non-Indians as well. Being lovely was not a criterion for Ojibwe names. One chief’s name is rendered as Sour Spittle, which hardly seems flattering. An Ojibwe scholar told me of a spiritual leader whose Ojibwe name means “yellow foam” — “like puke,” the spiritual leader explained.

Moreover, more than one Ojibwe chief was named Moose Dung. As late as the 1930s, the last chief of the Winnibigoshish band of Ojibwe was named Bob Mosomo.23 The Red Lake Chief Moose Dung (Mon-so-mo) is listed by that name (and his son as Mays-ko-ko-noy-ay) in the list of Ojibwa Personal Names in the Minnesota Historical Society’s 1911 Aborigines of Minnesota.

Further indication that the identification of both men as Red Robe is erroneous can be seen in To Walk the Red Road: Memories of the Red Lake Ojibwe People, a collection of oral histories and quotations from historical documents compiled by students at the Red Lake High School. The first portrait in the book has a photo of Red Robe (the same one used in the creation of the statue), but he is identified as “Moose Dung, Chief, Red Lake.” While technically correct (he was known as both Red Robe and Moose Dung the Younger), on the same page there is a quote from Moose Dung the Elder at the Old Crossing Treaty: “You have hit my heart in the right spot, in speaking of the liquor as you did. That is what I don’t want in my land, because it is the source of trouble and poverty.” He is identified as “Moose Dung, Red Lake Chief addressing the government representatives during negotiations for the Treaty of 1863.”24 Here two different people are conflated into one!

In the same book, Peter Graves, Red Lake leader from 1918 to 1957, refers to his grandfather as Moose Dung (in this case, clearly the father of Red Robe): “My mother migrated from Leech Lake and was married to a son of the old chief, Moose Dung. Moose Dung was one of the chiefs who made the first concession of land at the Old Crossings in 1863.”25

The name Moose Dung or Monsomo occurs in many documents, both historical and legal. Some might object that those were all written by non-Indians, but in the absence of clear evidence that this usage is incorrect, the scales seem weighted in favor of the name the chief used in signing the Old Crossing Treaty. Red Robe took his father’s name when the old man died, and even referred to himself as Monsimoh in court documents. That was also the case of news accounts from the period. Throughout its detailed 1899 ruling in Jones v. Meehan, the U.S. Supreme Court maintains the distinction between the two men, referring to “the elder Moose Dung,” “Moose Dung the younger,” and quotes from Moose Dung the Elder’s statements during the Old Crossing Treaty negotiations.

Conclusion

The most puzzling question behind the failure of the statue to accurately depict Red Robe is this: Why didn’t any of the Ojibwe object to the generic face on the statue? Red Lake historian Jody Beaulieu cast the apparent silence on the issue in a different light (though implicitly acknowledging that Red Lakers had not raised the issue): “It’s called liberation of the mind of the oppressed who are struggling to survive, but in spite of the oppression and poverty still have a sense of great pride and rightfully so!”26 Coming after a series of ripoffs, slights, and oppression at the hands of white people — including the grabbing of millions of acres of the most fertile land in the United States in 1863, the finagling to take Red Robe’s land away from him in the 1890s, the threats to pressure Red Lake into ceding the eleven western townships, the removal of the Ojibwe village and the digging up of the Indian cemetery in 1904, and the outright theft of the northern third of Upper Red Lake by U.S. Commissioner Henry M. Rice following the Treaty of 188927 — perhaps the Indians chose to hold their tongue about the flawed homage to their ancestor.

Notes

I would like to thank the following people for their help in my researching this article: Kathryn “Jody” Beaulieu, Caryl Bugge, Carstie Clausen, Rick Contos, Diane Drake, Gary Fuller, Marvin Lundin, Karen Mallea, Steven Mosbeck, Clara NiiSka, Diane Schwanz, Richard Sjoberg, Don Stewart, Donna Snyder, Donna Sumner, Anton Treuer, Jerry Vettrus, Madelyn Vigen, Bobby Whitefeather. They provided useful information, even if they may not share my conclusions.

1 “Removal of the Dead Indians,” Thief River Falls News, June 2, 1904, 1.

2 Wub-e-ke-niew, We Have the Right to Exist (New York: Black Thistle Press, 1995), 146.

3 “Looks Like an Early Opening,” Thief River Falls News-Press, April 7, 1904, 1.

4 The site of Silent City is indicated on a hand-drawn map on the inside cover of We Choose to Remember: More Memories of the Red Lake Ojibwe People, a book of reminiscences of Red Lake elders compiled by the students of Project Preserve (no date, but after 1989, when an earlier volume of memories appeared).

5 A curious item appeared in the Thief River Falls News right after the land sale began, titled “Petrified Indians”: “The Minneapolis papers have long strings about the work of Joe Duchamp, of this city in regard to the removal of the dead Indians. According to the articles Joe has all kinds of petrified Indians which he found on the reservation and is selling them for cigar signs and hitching posts” (Thief River Falls News, June 23, 1904, 1). Apparently, Duchamp either diverted some of the remains for sale elsewhere or he was engaging in creative fraud.

6 Ella A. Hawkinson, “The Old Crossing Chippewa Treaty and Its Sequel,” a paper read at the 85th meeting of the Minnesota Historical Society, January 8, 1934 (collections.mnhs.org/mnhistorymagazine/articles/15/v15i03p282-300.pdf, 294).

7 Articles of a Treaty Made and Concluded at the Old Crossing of Red Lake River (October 2, 1863), 38th Congress, United States Congressional Archives, 40-45.

8 Grand Forks Herald, September 25, 1988; quoted in “Red Lake History — The Beginning” (www.rlnn.org/MajorSponsors/HistoryProjectBeginning.html) and in a memo to Madelyn Vigen, Director, Thief River Falls Parks and Recreation Board, from city Community Development Director Don Stewart (July 1997) about the revised text for the plaque on the Red Robe statue.

9 Copy of text in files of the Thief River Falls Parks and Recreation Board. The text does not seem ever to have been published (at least not in the local newspaper). A revised plaque text appears on the statue today (text below).

10 A thorough examination of Red Robe’s dealings with lumbermen seeking his land, as well as court cases involving issues like title to the land and disputes between whites seeking to lease the land, is provided in Steven Mosbeck’s monograph “The History of Moose Dung’s Section and How the Section Influenced the Settlement of Thief River Falls” (March 27, 1975). The cases involved determining whether Red Robe owned the Chief’s Section or if it was part of Red Lake, a result of a lease for the same small strip of land being granted to both Patrick and James Meehan in 1891 and Ray W. Jones three years later. Jones claimed that the original lease was invalid on grounds that the land belonged to the tribe, not to Red Robe. The Meehans already had a sawmill on the river, and Jones wanted to build a competing one. The dispute went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled on October 30, 1899, that since the tract was given to Moose Dung the Elder at the Old Crossing Treaty, it was his and his descendants’ land, not that of the tribe as a whole. Thus, the 1891 lease to the Meehans was upheld as legal.

11 Phone conversation with Jerry Vettrus, May 13, 2011. The 1885 photograph of Red Robe with Albert Stately is in the photograph collection of the Minnesota Historical Society.

12 E-mails to the author, November 21 and November 24, 2011.

13 Photographs of these and other Indian statues can be seen at <agilitynut.com/giants/indians.html>.

14 Marvin Lundin, “Grandson of Indian Chief Would Like Proper Name: Mon-si-moh Was Really Mays-co-co-nah-yay,” Thief River Falls Times, July 19, 1976, 1.

15 Thief River Falls Times, July 14, 1976, 8 (photo caption).

16 Don Stewart, interview with the author, February 23, 2011.

17 Because names used in this article appeared with different spelling conventions, I am using various spellings. Red Robe is sometimes translated as Red Robed, Red Blanket, or “the one that wears the red robes.”

18 Mary Croteau, Where Two Rivers Meet: A Diamond Jubilee History of Thief River Falls (no publisher, 1971), 2; 2d ed., co-ed. Bonnie K. Swantek, published by the Thief River Falls Times, 1996.

19 Frances Densmore, Chippewa Customs (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1979), 52.

20 Ibid., 53.

21 Tom Lussier, in To Walk the Red Road: Memories of the Red Lake Ojibwe People, Project Preserve, published by the Red Lake Board of Education (1989), 89.

22 E-mail to the author, March 2, 2011. Whitefeather was tribal chairman in 1976 when the statue was erected.

23 Thanks to Donna Snyder for this information about her ancestor Bob Mosomo.

24 To Walk the Red Road, 2.

25 Ibid., 11.

26 E-mail to the author, November 18, 2011.

27 Red Lake chiefs drew the lines of the reservation and Rice redrew them to slice off the northern and eastern edge of Upper Red Lake, making Waskish part of white land and getting the stolen land incorporated into the agreement and accepted by Congress. Red Lake didn’t learn about this swindle until a year later. See “The Treaty and Agreement of 1889 with the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians,” minutes from Erwin F. Mittelholtz, Historical Review of the Red Lake Indian Reservation (uts.cc.utexas.edu/~woss/redlake2/redlkmin.html). See also Dan Needham’s description of this theft in To Walk the Red Road, 5-6.

David Thorstad is a former president of New York’s Gay Activists Alliance, a cofounder of the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights, a cofounder of the North American Man/Boy Love Association, coauthor of The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864-1935), and editor of Gay Liberation and Socialism: Documents from the Discussions on Gay Liberation inside the Socialist Workers Party (1970-1973). His writings are available at <www.williamapercy.com/wiki/index.php?title=David_Thorstad>.

| Print