Imagine a world without capitalism.

Jennifer Dalton, Ask Not for Whom the Art is Intended, 2015. Courtesy of the Museum of Capitalism.

That simple yet seemingly impossible task is at the core of the Museum of Capitalism, a new speculative institution set to open its doors in Oakland, California, on June 17th. Through August 20th, the free museum will examine the complex mechanisms and consequences of, and forms of resistance to, the world’s primary economic system through works by over 60 artists, a library, a full calendar of public programming, and, fittingly—or perhaps ironically—a gift shop.

Visitors will be invited to reflect on capitalism as if looking back at it from a world in which capitalism is dead. “Much of the evidence of capitalism is either eroding over time or simply not known or easily accessible to the public,” the mission statement reads. “Our ambition is to connect and integrate these many efforts before the evidence is erased forever.”

The project was conceived by curatorial duo Andrea Steves and Timothy Furstnau, who registered the MuseumofCapitalism.org domain back in 2010, when British political theorist Alex Callinicos suggested, while speaking on a panel, that one day there would be a museum to memorialize capitalism, just as we have museums of apartheid and communism today.

But it wasn’t until Steves and Furstnau received the annual Emily Hall Tremaine Exhibition Award for nearly $150,000 that the proposition finally came into focus. The Tremaine Foundation’s Art Program Manager Heather Pontonio says the award (the largest of its kind in the country) is reserved for daring proposals that other foundations typically wouldn’t fund.

Superflex, Bankrupt Banks Flags. Courtesy of the Museum of Capitalism.

“If it would be [otherwise] funded, it’s probably not challenging enough,” she says. “It’s probably not taking that level of risk that we would like to see taken.”

And with past recipients of the award including Mass MoCA and the Queens Museum, the Museum of Capitalism is an especially remarkable winner: It’s the first ever awardee that isn’t an existing museum, but rather a project that takes the museum as its form.

That’s not to say that the platform won’t look and feel like a typical museum once it’s open. The space holds two exhibitions—a core exhibition and a “special exhibition” about American imperialism, curated by Erin Elder and featuring works by Bruce Nauman and Chip Thomas, among others.

For the core exhibition, curators chose and commissioned works from a provocative group of artists—Superflex, Dread Scott, Curtis Santiago, andSadie Barnette, among others—that interrogate capitalism from a multitude of angles. What emerge among these objects is a series of implicit sub-themes, such as global trade, race, incarceration, and the environment.

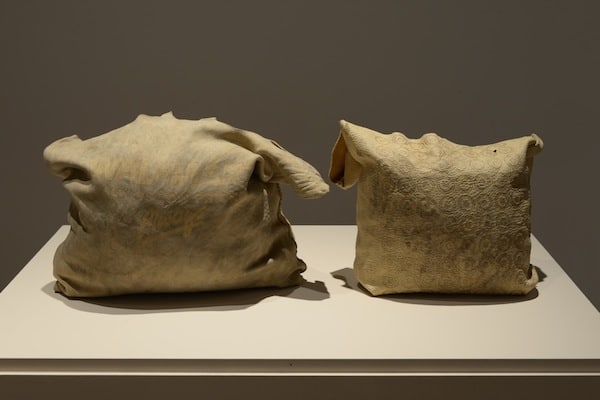

Jordan Bennett, Artifact Bags (The Bay, Walmart and Target), 2013–15. Courtesy of the Museum of Capitalism.

As standalones, most of the works wouldn’t necessarily register as being about capitalism. Take Sadie Barnette’s piece, for instance: A series of order forms for gold teeth, with shimmering spray paint and cheap gem stickers embellishing the anatomical diagrams of teeth. But Barnette describes gold teeth as one of the tools of black visual culture for surviving capitalism—a tool for “making yourself feel like you’re worth more than society tells you that you are,” she says.

The central exhibition also includes an interactive installation by Hong Kong artist Christy Chow, in which visitors run on a treadmill while video screens take them through the step-by-step process of assembling a garment in a Chinese factory.

Oakland-based Vietnamese-American artist Gabby Miller, meanwhile, will show a massive piece of a steel container as part of a sculpture reminding us that the Vietnam War was largely made possible by shipments of supplies via container ships going directly from the Oakland Port to South Vietnam.

And in documentation of Rimini Protokoll’s “Annual Shareholders Meeting,” the Berlin collective sells “tickets” to a performance that are actually small amounts of Daimler stock, inviting theatergoers to attend the automobile company’s annual shareholders meeting to see capitalism performed live.

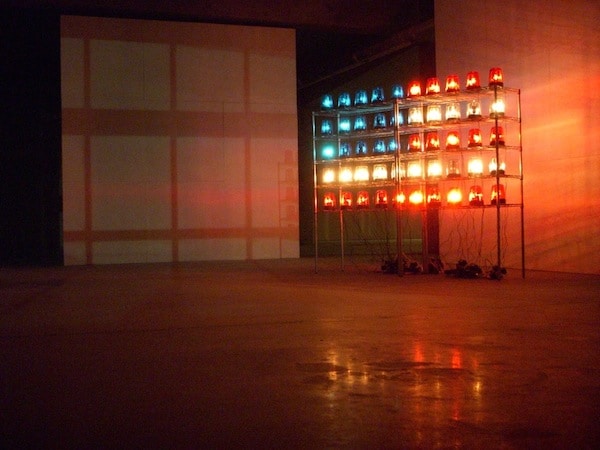

Blake Fall-Conroy, Police Flags, 2009. Courtesy of the Museum of Capitalism.

It’s works such as Rimini Protokoll’s that emphasize the Museum of Capitalism’s surreal setting.

The museum’s temporary location is tucked away in Oakland’s Jack London Square, a developed waterfront area that was initially envisioned as a tourist destination but has been plagued with storefront vacancies for the past decade—and is eerily deserted on most days of the week.

Steves and Furstnau partnered with the Jack London Improvement District to move into a massive empty building that was designed to be a bustling vendor marketplace.

To reach the museum from the street, visitors must cross railroad tracks via an elevated walkway with a sci-fi feel. Once in the second-floor exhibition space, they can peer down into the still-vacant first floor of the building and see scaffolding left behind like a ghost of the intended marketplace—almost a work of art in itself.

At the back, floor-to-ceiling windows look out onto the Oakland Estuary, where rows of yachts bob in the water and massive cranes lift containers onto ships in the distance, ready to carry them across the world.

Without the Museum of Capitalism there, the area would seem ordinary to any Oaklander. But part of the museum’s goal, the curators explained, is to invite visitors to imagine alternatives outside of capitalist frameworks, simply by suggesting the possibility of such a thing.

In doing so, they hope museumgoers will begin to recognize the ways in which we all perform capitalism in our daily lives, making people aware of the way it’s both ubiquitous and invisible. As Steves put it: “The exit of the Museum of Capitalism is the entrance to the real museum of capitalism.”