Given the thick haze of disinformation surrounding the economic situation in Venezuela, we thought it would be useful to publish the first chapter of Professor Pasqualina C. Curcio’s excellent volume, The Visible Hand of the Market: Economic Warfare in Venezuela (available for free online). We are grateful to Steve Ellner for writing a brief introduction to Professor Curico and the excerpted chapter. Note that the present version has been edited from the original PDF to improve readability. —Eds.

Introduction by Steve Ellner

For several years, university professor Pasqualina C. Curcio has presented a wealth of empirical information in order to refute the notion that market logic, government incompetence and a flawed socialist model are responsible for the severe problems of shortages and inflation that afflict Venezuela. In The Visible Hand of the Market: Economic Warfare in Venezuela, Curcio discards the various explanations put forward by the Venezuelan opposition and the corporate media and concludes that the shortages have been induced as has the nation’s triple-digit inflation. The shortages are the result of hoarding and contraband, not due to the decline in national production or the failure of the government to provide the commercial sector with the necessary foreign currency to pay for imports. In fact, for the years that she analyzes between 2003 and 2013, the correlations claimed by government adversaries were not borne out by the facts: declining national production did not produce shortages nor did the state’s failure to sell sufficient dollars to finance imports. Furthermore, the types of goods that are in short supply are those controlled by oligopolistic companies, as opposed to small-sized businesses. All this demonstrates that what Curcio calls “planned shortages,” or economic sabotage, are largely responsible for the pressing economic problems facing the nation, similar to the case in Chile under Allende and in other leftist-governing nations throughout history.

Chapter I. Planned Shortages1

Shortage, along with inflation, is one of the two main hardships that Venezuelans have been facing from the economic and social point of view since mid-2012. Both phenomena have repercussions not only on aspects related to the economy of households but also on the standards of living of the population.

Shortage has been particularly apparent in the case of essential items, such as food staples, medicines, toiletries and household products. But shortages have also extended to raw materials and inputs necessary for local production, including agriculture, and machinery spare parts for the manufacturing sector; as well as goods essential to invigorate and mobilize the economy, such as the transport of goods and people, has been hard to find – car spare parts, accumulators, among others.

Even goods necessary for health care, with a great possibility of negatively impacting the standards of living of the population, have also been unavailable. Particularly medicines for outpatient and hospital use, as well as surgical equipment used in health care facilities.

Interestingly, shortage is rather more frequent in the case of goods than in the case of services. This issue is analysed later so as to understand both part of this phenomenon and draw a clear distinction between economic crisis and economic warfare.

While inflation is analysed in detail in the next chapter, it is worth discussing its wicked effects on the social and economic situation of households, particularly those depending on a salary for labour (as the only factor of production they own). Households whose income derives from the profits of the capital are in a better position to adjust their income to the levels of inflation. In Venezuela, as in all countries, most households live on a salary.

Inflation deteriorates the purchasing power of workers, thus forcing them to reschedule their spending structure and prioritize the satisfaction of their basic necessities – food, transport and medicines. In other words, and in terms of the economy as a whole, inflationary processes of this type in the medium and long term will adversely affect the sectors of the economy, as a result of a decrease in the demand for other items due to the shrinking purchasing power of the working class. Failure to address inflationary phenomenon can result in serious economic situations in the medium term.

So far I have said nothing new. Venezuelans have experienced this. Further, the Government has denounced, nationally and internationally, such destabilization plans, labelling them as “economic warfare” and has announced and taken measures to counter them accordingly.

This work is intended to demonstrate—with data, official figures and economic analysis—that shortage and inflation result from destabilization and manipulation plans carried out by specific sectors, and are not the result of macroeconomic imbalances caused by a failed model, as argued by opposition sectors.

Before starting such analysis, it is important to bear in mind the arguments that sectors opposed to the Government have positioned through mass and social media in connection with the economic situation of the country.

Critics repeatedly use the term “crisis” when referring to the economic situation, which they attribute to a failed model that has negatively impacted macroeconomic indicators. Their rationale can be summarized as follows:

We, Venezuelans, are facing one of the worst economic crises we have ever experienced; we do not have food to eat because there is no food available; we are subject of a great shortage of goods and services. The shortage is due to the fact that the Government has not delivered the foreign exchange to the business sector to import both raw materials and end goods which are not produced in the country. Unable to import these goods, production drops and with an ever growing demand, shortage is generated, thus pushing prices up. All this occurs because of a failed model that prevents the Government from responding to the serious economic crisis we are enduring.

In short, the opposition sectors argue that the Government has not delivered the dollars necessary to supply Venezuelans with affordable goods, thus causing shortage and inflation.

Emerging concerns leading to this research

Given these arguments, we ask the following: how much has the delivery of foreign exchange to the business sector changed since the establishment of the new social, economic and political model in Venezuela? What is the relation between this alleged decrease in foreign exchange delivery and the level of imports, both in monetary terms and in physical units? How much has the consumption of Venezuelans increased in recent years with respect to the supposed decrease in production and imports? How much has the unemployment rate increased in the last seventeen years as a result of the decline in production?2 Why are certain food items more difficult to find than others? Why are certain food items in ample supply for wholesale purchasers (e.g., wheat flour and butter used by bakeries) and not on supermarket shelves?

With respect to inflation, we ask: What is the relationship, if any, between inflation and shortage? To what extent do changes in aggregate demand (composed among other variables by household consumption) explain the variation in prices? Is there any other factor associated with the rise of prices, besides aggregate demand, that would explain this phenomenon in Venezuela?3

To what extent has the exchange rate in the so-called “parallel market” affected the price index of the real economy?4 What is the relationship, if any, between the exchange rate in the so-called “parallel market” and the level of international reserves?5

As mentioned above, this chapter focuses on the analysis of planned shortages in Venezuela. Inflation is discussed in the succeeding chapter.

Shortage, production, imports, delivery of foreign exchange and consumption

Shortage

According to economic theory, shortage in markets originates either due to an expansion of demand, which is not answered by an increase in supply, or a contraction of supply given a demand. In other words, if consumers demand more goods than they used to and there is no response from suppliers, there will be a shortage in the market (where more goods are demanded than those supplied).

The first manifestation of shortages, according to economic theory, are the queues (the first person to arrive buys the good); another manifestation is the displacement to a parallel market with higher prices (especially if they are goods whose prices are controlled); a third manifestation of shortages is the increase in prices in such markets (people are willing to pay more for the scarce good).

At this point, it is worth asking why consumers demand more quantities of a given good. Consumer theory clearly establishes the factors involved: either because consumer income increased,6 tastes have changed, or expectations have changed.

This last factor, of a mainly psychological nature, has largely explained the consumer behaviour in Venezuela in recent months. News and public opinion campaigns that seek to influence expectations have led to the expansion of demand for some goods.7 This demand will continue expanding as long as the “expectations” variable remains influenced by opinion campaigns.

If an expansion of demand in the market occurs and there is no response from the supplying agent or producers, or worse, the supply of the good in question shrinks, a greater shortage will be generated and, therefore, a greater pressure on the prices of these goods.

But why does supply shrink? Theoretically, it is due to a decrease in levels of production, or in the Venezuelan case, because the levels of imports of goods decreased, or because, even if goods are still produced or imported, they are not available in the markets, which is known as hoarding.

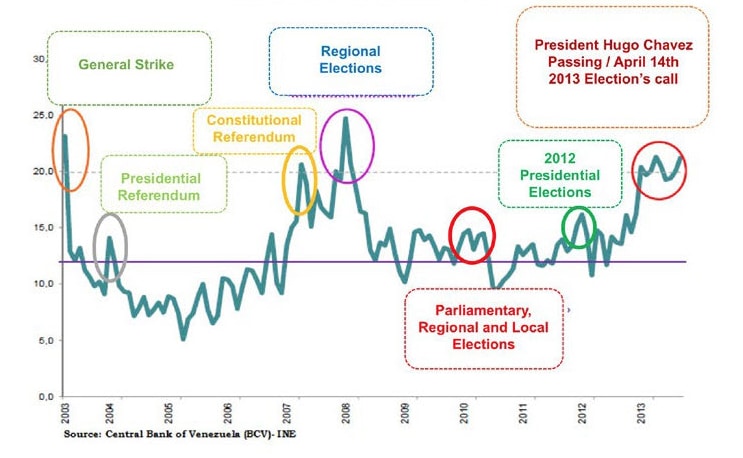

Shortage in Venezuela did not take place in recent months only, but rather is a phenomenon that we have seen with some intensity during the last several years. Figures from the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV in Spanish) and the National Statistics Institute (INE in Spanish) indicate that shortages reached an average of 13.1% between 2003 and 2013.8

A careful analysis of Chart 19 shows that since 2003 we have been facing episodes of significant shortages, the first one taking place during 2003, when the level of shortage amounted to above 25% due to a general strike and to the oil industry sabotage to which the Venezuelan economy and people were submitted.

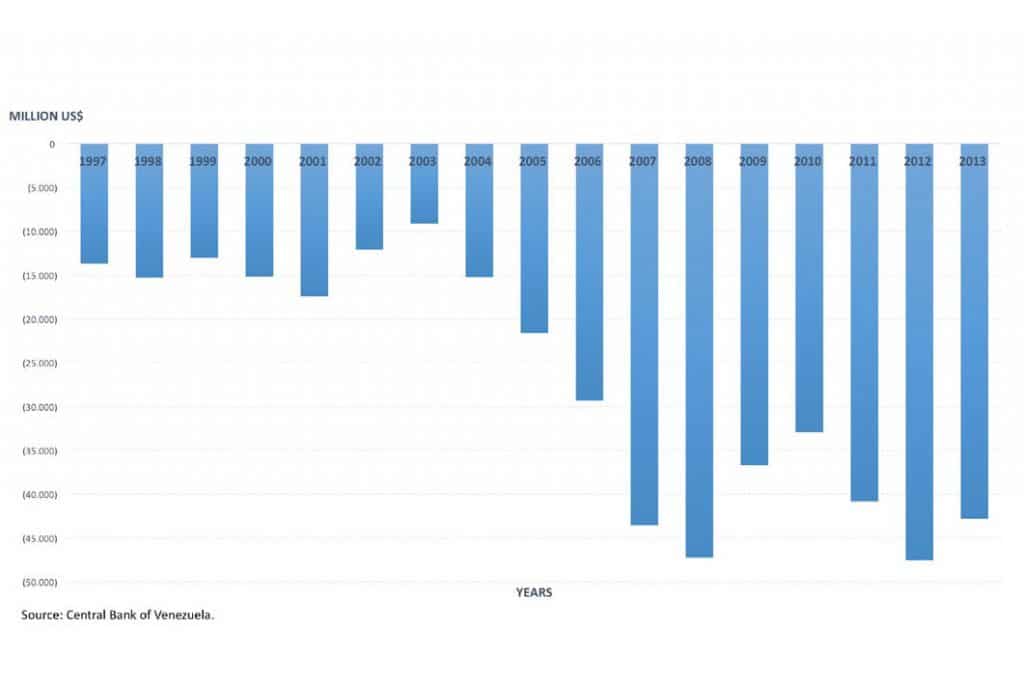

Chart 1. Rate of Shortages, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2003–2014

Subsequently, levels of shortages were seen between 2004 and 2005, shortages showed a decreasing trend, with a stable yearly average of around 7%.

Since 2006 the trend of this indicator has evidently undergone a change, increasing to a record 26% in 2007. From 2008 to 2010, shortages fell sharply to an average 13% and from 2011 onwards the upward trend resumes climbing above 20% in 2013.10 Chart 1 also shows the relationship between shortages during peak periods and the political conditions at that time, especially during 2007 when the constitutional reform referendum was carried out, as well as other electoral events.

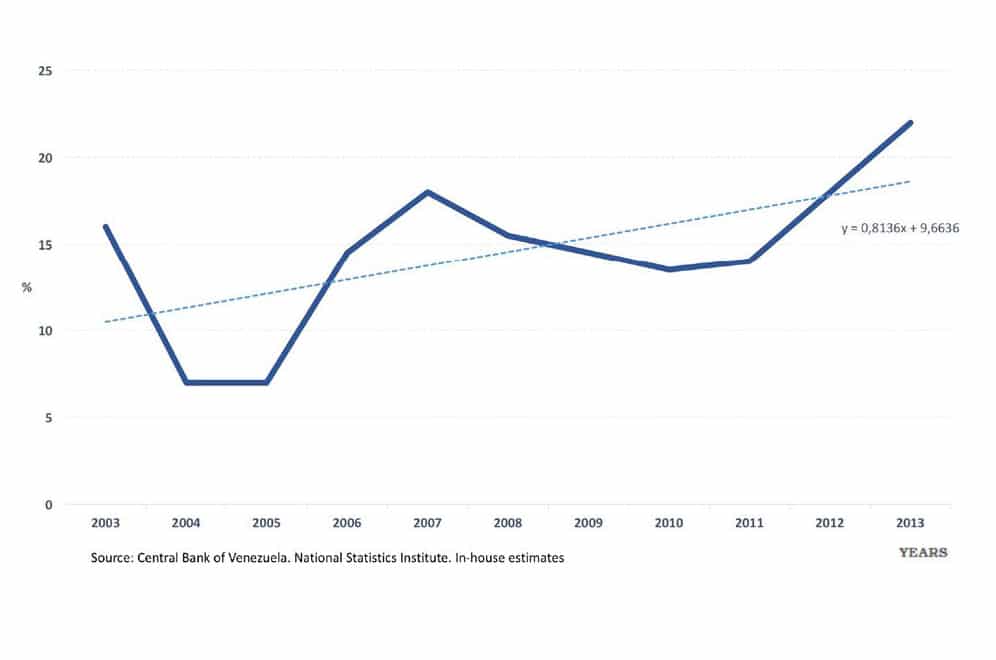

Overall, there is an upward trend in shortages over the 2003- 2013 period. Chart 2 shows the annual average of shortages and the trend for the 2003-2013 period.

Chart 2. Annual average rate of shortages, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2003–2013

As mentioned above, theoretically, it is expected that an increase in shortages is associated, on the one hand, with a decrease in production and/or imports as a consequence of a decrease in the delivery of foreign exchange by the Government to the private sector and, on the other hand, to an increase in consumption by both households and Government.

As mentioned above, theoretically, it is expected that an increase in shortages is associated, on the one hand, with a decrease in production and/or imports as a consequence of a decrease in the delivery of foreign exchange by the Government to the private sector and, on the other hand, to an increase in consumption by both households and Government.

The behaviour of each of these variables in 2003-2013 is shown below including comparisons with the shortage rates.

Production

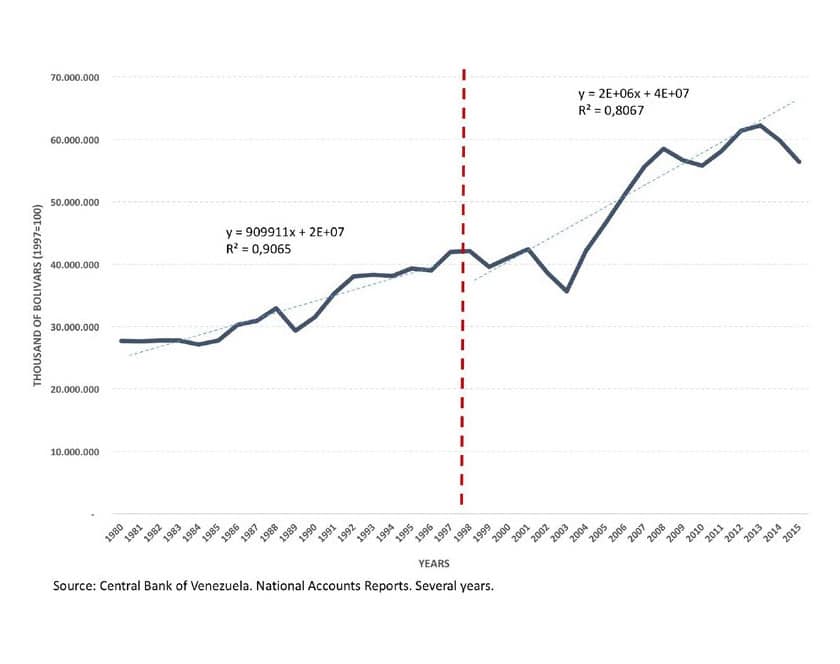

Chart 3 shows the 2003-2013 GDP measured in constant 1997 prices and expressed in billions of bolivars. The GDP trend is rising on average during the period under study. There is evidence of sustained growth from 2003 thru 2008, and then the trend changes during 2009 and 2010 and subsequently regains its upward movement. We cannot see in the chart a sharp decline of the GDP that may explain the shortage rates that have been reached in the economy.

Chart 3. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 1980–2015

The same chart shows the trend of the shortage rate. No empirical relationship between both variables exist so as to support the allegations argued by some sectors opposing the Government—that is, that the shortage rates are caused by the decline of domestic production.

On the contrary, we observe that in 2006 and 2007 an increase in the shortage rate even as the level of national production increased. A similar situation occurs in 2011. Further, between 2008 and 2011, there is a declining trend in the shortage rate despite a fall in domestic production.

In short, the decrease of domestic production does not explain the shortage rates in the economy.

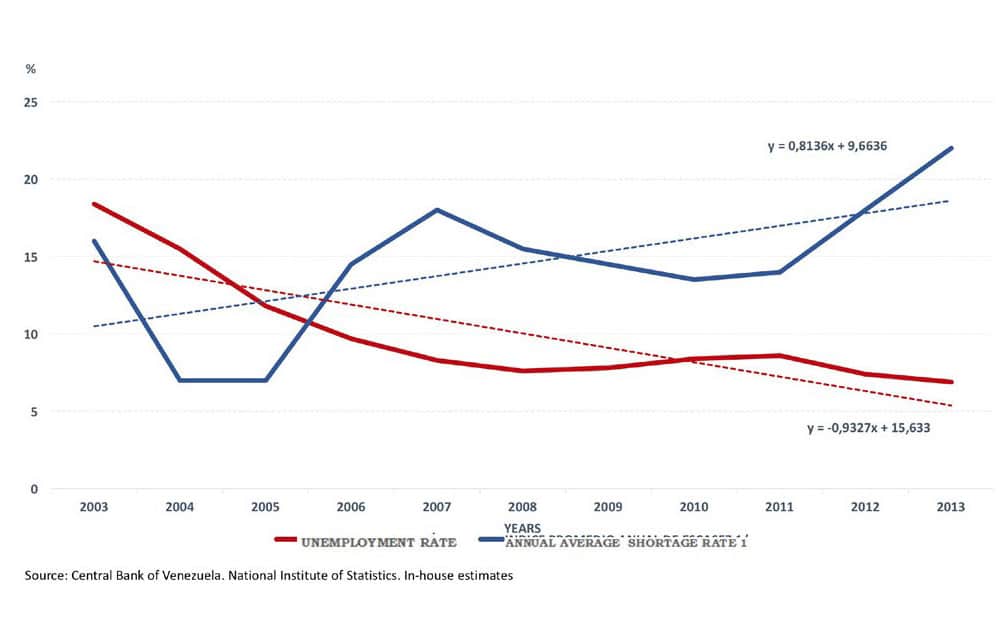

The GDP behaviour and its upward trend during this period can be consistently observed as well in the behaviour of the unemployment rate for the years under study. Chart 4 shows the unemployment rate from 2003–2014, recording a downward trend over this period. This rate is compared in the chart against the shortage rates. No logical relationship between the two of them can be found. High shortage rates should be correlated with high unemployment rates. However, the opposite is evident in the Chart 4.

Chart 4. Annual average rate of shortages and unemployment, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2003–2013

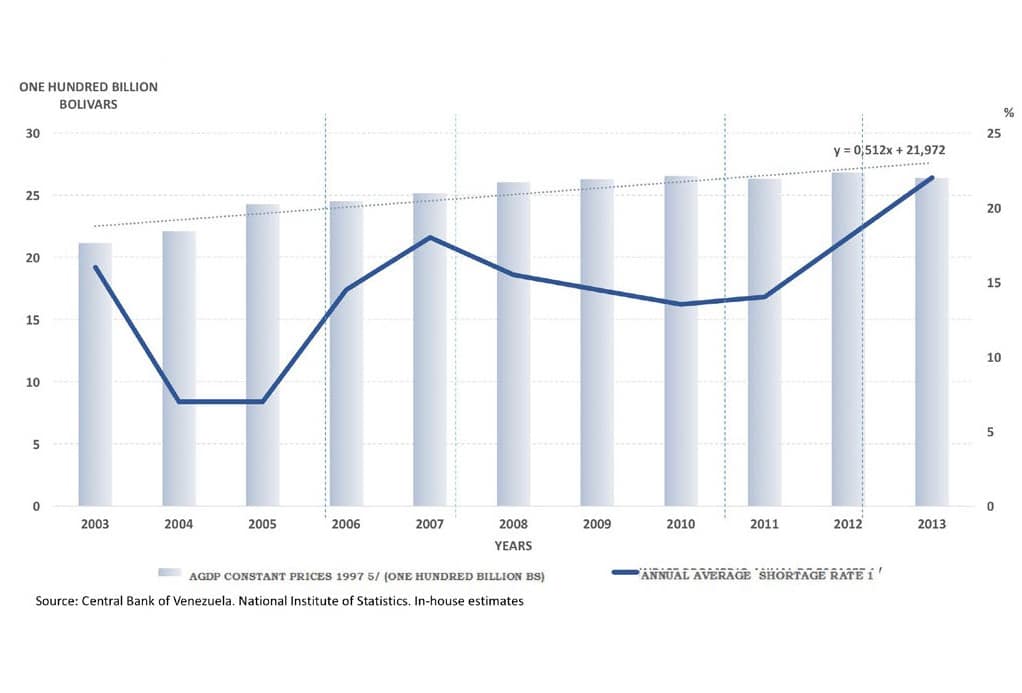

Since most of the food products subject to shortages belong to the market basket, we decided to compare the shortage rate against agricultural production, as measured by the agricultural component of GDP (at constant 1997 prices in billions of VEF). The results of the analysis are similar to the analysis conducted with GDP. There is no empirical relationship between the shortage rates and the agricultural component of the GDP. On the contrary, the agricultural component of the GDP shows an upward or at most a stable trend (see Chart 5).

Chart 5. Annual average rate of shortages and agricultural GDP, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2003–2013

The growth periods of the shortage rate do not correspond to abrupt declines in agricultural production, especially in the 2006-2007 and 2011-2013 periods.

Imports

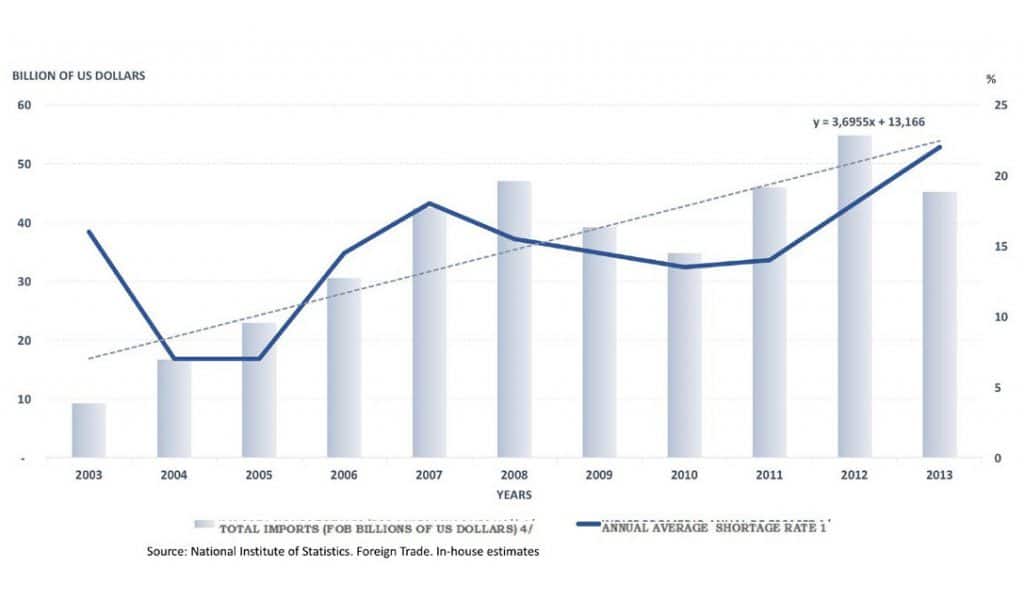

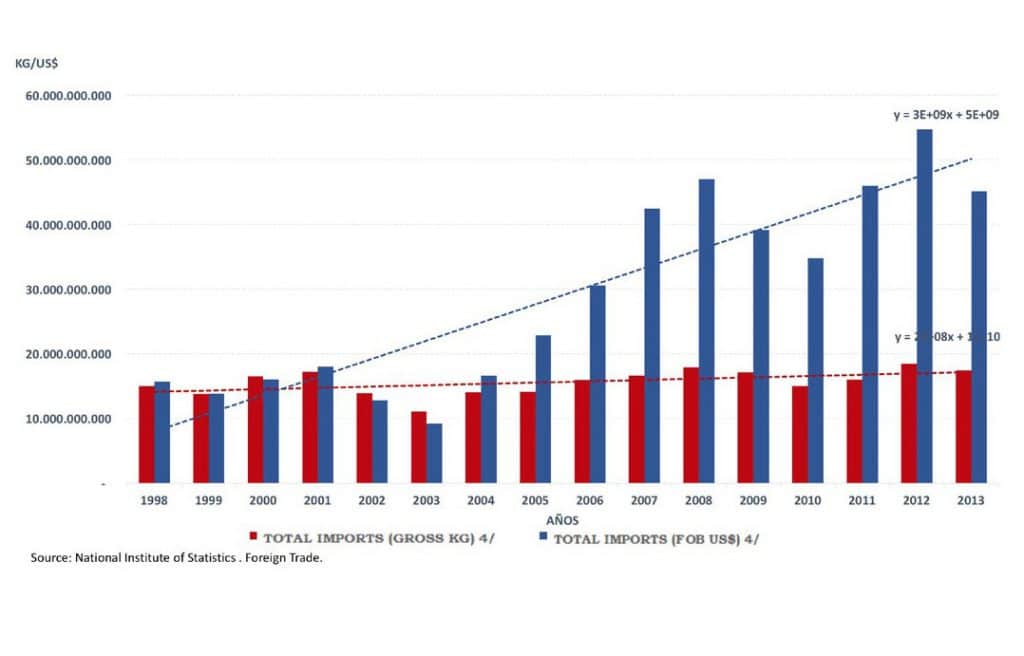

In this section, we compare the shortage rates against the 2003- 2013 level of imports, and like the case of production levels, there are no empirical elements to affirm that shortage in Venezuela is caused by a reduction in imports of goods. On the contrary, Chart 6 shows, firstly, that there is an average upward trend of total imports of goods for the period 2003-2013 of 388.9%.

Chart 6. Annual average rate of shortages and total imports, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2003–2013

Total imports hiked 408.8% in 2003-2008. Yet, the shortage rate grew during those years. Between 2006 and 2007, the shortage rate grew 25% even though imports grew 39%.

We also observe that the decrease recorded in the total levels of imports in 2008 and 2009 has not resulted in an increase of the shortage rate, which contrarily, shows a decline as well. Likewise, from 2010 imports increased once again while the shortage rates begin to grow in 2011.

In other words, there is no correspondence between the behaviour of the shortage rate and the total level of imports. Therefore, allegations by sectors of the opposition that shortages in Venezuela are caused by a decrease in imports as a result of the failure by the Government to deliver foreign exchange to the private sector has no empirical support.

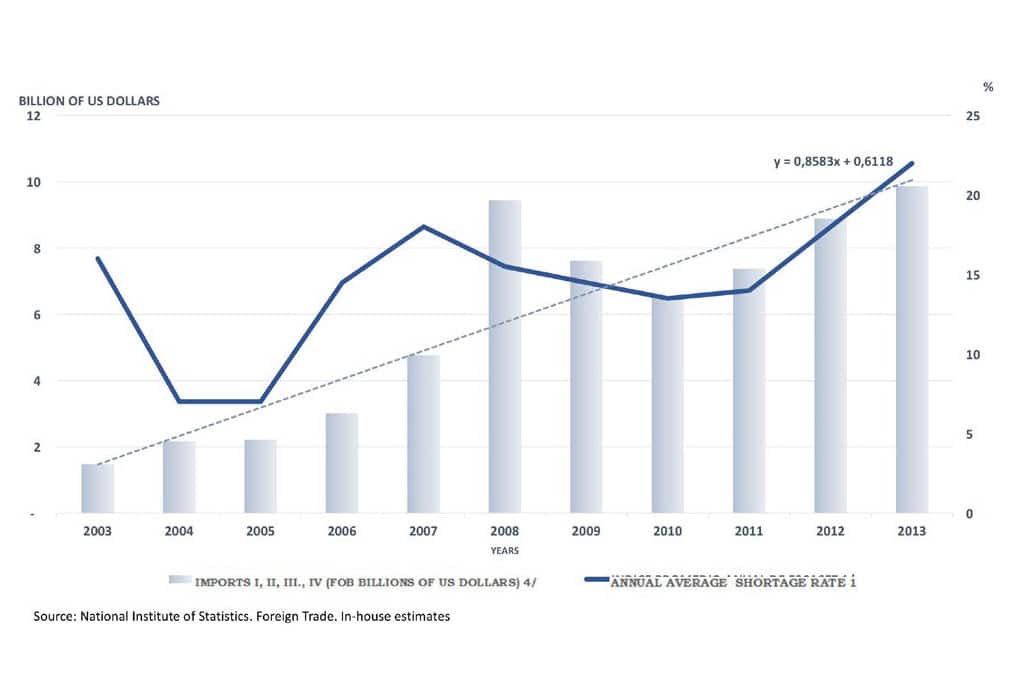

Just like in the case of the analysis of production we compare imports of food11 against the shortage rate. There is no relationship between the behaviour of both variables that allows us to affirm that the shortage of food, mainly, is caused by a decrease in food imports. On the contrary, according to official data issued by the National Statistics Institute, food imports, measured in dollars, increased by 571.7% between 2003 and 2013, as shown in Chart 7.

Chart 7. Annual average rate of shortages and food imports, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2003–2013

Chart 7 also shows that both variables trend in the same direction—the increases in food imports correspond to increases in the shortage rates.12 From a conceptual and theoretical point of view, this is not at all what we would expect if opposition claims were true. The shortage of food is not caused by a decrease in the import of food products—quite the opposite, food imports have increased.

Foreign exchange allocated to the private sector

Basically, Venezuela produces and exports a single product: Oil. The oil industry is owned and run by the State. This commodity, on the other hand, is a product that has marked the current economic era and is quoted and traded in U.S. dollars. This means that the Venezuelan State receives all the proceeds of the Venezuelan oil trade. So, for an average increase of imports by 388.9% between 2003 and 2013, it is necessary that the State allocates foreign exchange to the private sector.

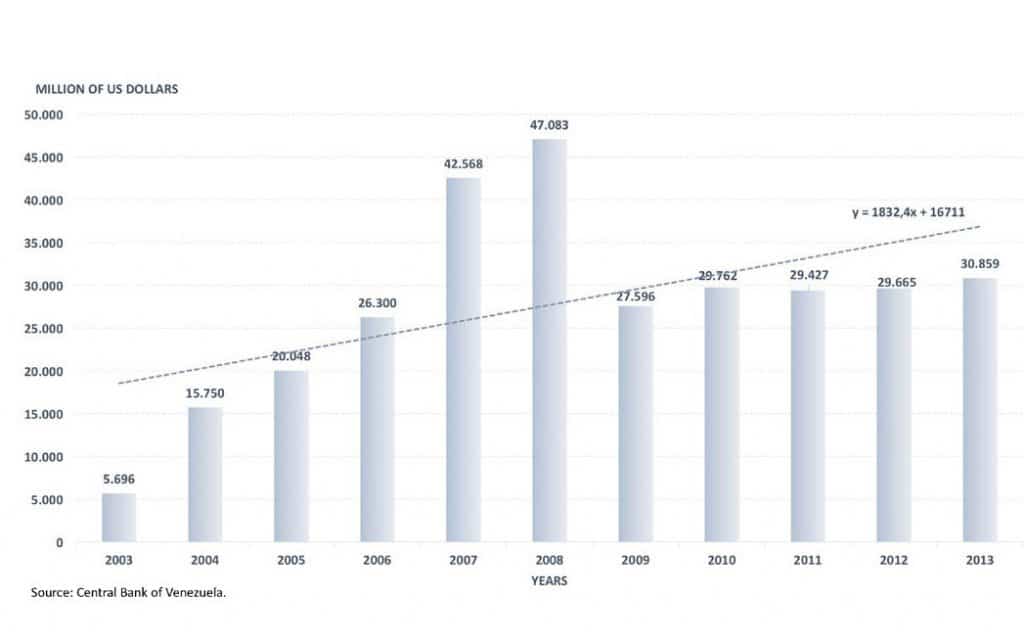

In this connection, from 2003 through 2013 the Venezuelan State has allocated US$304.7 billion to the private sector—US$5,695 million were allocated in 2003 and US$30,859 million in 2013. This represents an increase of 442% during the period under study, as shown in Chart 8.13

Chart 8. Foreign currency granted to the private sector, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2003–2013

Between 2003 and 2008 the allocation of foreign exchange to the private sector increased by 727%. Then, In the 2009-2010 period, the amount of foreign exchange allocated decreased and regained the upward trend in 2011.

It is important to emphasize for the purposes of this analysis that the annual amount of foreign exchange allocated to the private sector during this period has never been lower than the amount allocated in 2004—even taking into account the decrease in 2009 and 2010. On the contrary, such levels always surpassed those in 2004. We make this specific comparison with 2004 because this is the year in which the lowest shortage rates were recorded.

In other words, shortage rates are not determined by the a decrease in the allocation of foreign exchange to the private sector, as argued by opposition sectors.

The analysis performed so far can be summarized as follows:

- The production levels of the economy during 2003-2013, measured by total GDP and agricultural portion of the GDP, have recorded an average increase of 75%, and 25% respectively.

- Total and food imports, measured in dollars have recorded an average increase of 388.9% and 571.7% from 2003 to 2013 respectively.

- The foreign exchange allocated to the private sector by the State recorded an average increase of 442% during 2003-2013.

- The shortage rates increased by 38% between 2003 and 2013.

The preceding analysis has given rise to the following question: If the foreign exchange has been allocated to the private sector to satisfy the import of goods required in the economy, and if imports (measured in U.S. dollars) have increased along with production, what is the reason for shortages? Posed in a different way, what is the explanation for shortages of some items in Venezuela?

Theoretically, as indicated at the outset, shortages can be explained by a decrease in production and/or imports, or an increase in final consumption, both of households and Government. That is, to justify shortages in empirical terms one would expect consumption to increase in a higher proportion than the increase of production and imports.

In this connection, the following section discusses the behaviour of consumption in relation to the increase in production and imports during the period under study.

Consumption

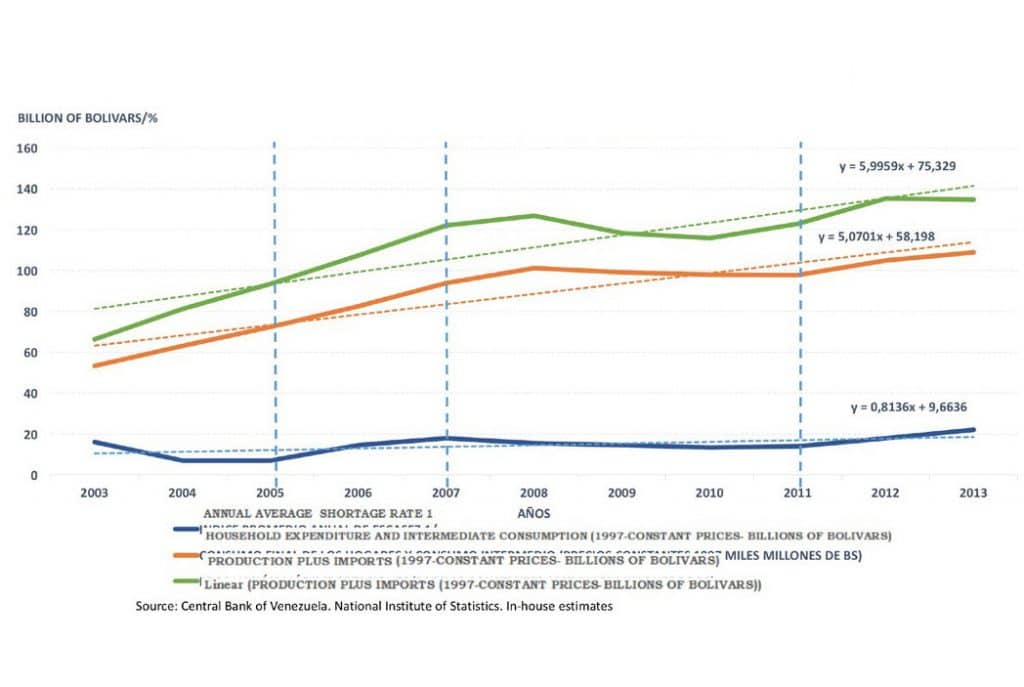

Chart 9 shows the trend of total consumption from 2003 through 2013. Total consumption is composed of intermediate consumption and final consumption which, in turn, includes the final consumption of households, Government and private non-profit institutions.

Chart 9. Annual average rate of shortages, final and intermediate consumption, and total production and imports, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2003–2013

Indeed, total consumption shows an upwards trend that can be observed throughout that period. However, the average growth rate of consumption during those years is lower than the average growth rate of total production and imports which is also shown in Chart 9.14 In this sense and with this first observation, we can say that the shortages that are also shown in the chart are not explained by the fact that consumption has been much higher than what has been produced and imported.

A second look at the chart shows that, contrary to what was theoretically expected, during 2006-2007, as mentioned above, when the shortage rates grew, production and imports were proportionally higher than consumption. The same occurred from 2011 onwards. On the other hand, in periods where the shortage rate decreased, production and imports decreased at a higher proportion than consumption, particularly between 2008 and 2010.

This chart suggests that there is no correspondence whatsoever between the shortage rate and consumption, production and import levels. Therefore, the levels of shortage recorded must be explained by other factors.

If the data suggest that the goods were produced and that increasing monetary resources were used for importation, the emerging question would be why they are not available on the shelves of local markets.

In analysing in detail the total imports of goods in 1998-2013, we observe that, since 2003, the increase in imports expressed in dollars is proportionally higher than the increase in imports expressed in gross kilograms (see Chart 10).

Chart 10. Imports of total goods and services by value and weight, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 1998–2013

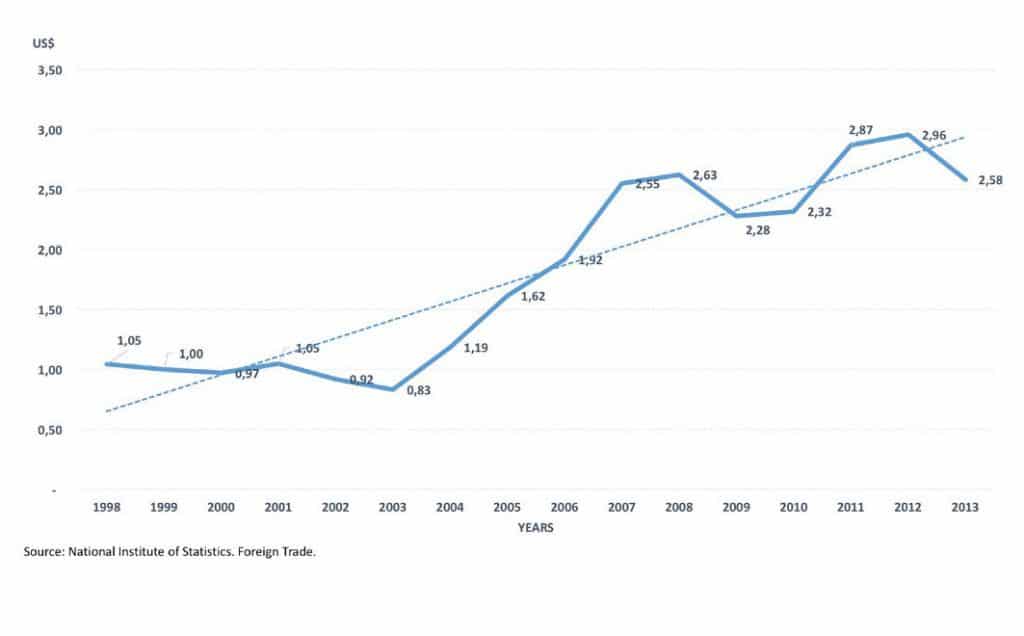

The variation in total imports of goods and services expressed in dollars was 388.9% when comparing 2003 and 2013, as we mentioned in the preceding paragraphs. However, in comparing total imports of goods and services, now expressed in kilograms, we found that the variation between 2003 and 2013 was 57.6%. In other words, we have imported less goods and services with more dollars allocated. Or, put in other words, the average cost of import per kilogram in 2013 was 210% higher than in 2003: 0.83 USD/ kg in 2003, as compared with 2.34 USD/kg in 2013. (See Chart 11)

Chart 11. Cost per kilogram of imported goods, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 1998–2013

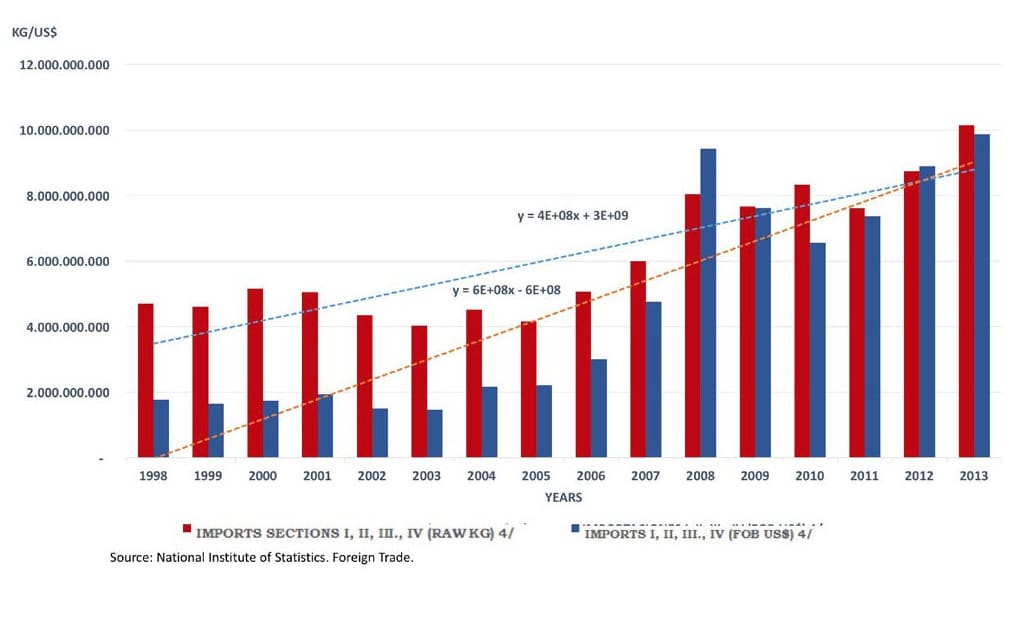

In the case of food imports, something similar occurred: The 2003-2013 variation in imports, expressed in dollars, was proportionally higher, 575.7%, than the increase in imports in gross kilograms for the same period, 151.5% (see Chart 12).

Chart 12. Imports of food products by value, weight, and per kilogram, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 1998–2013

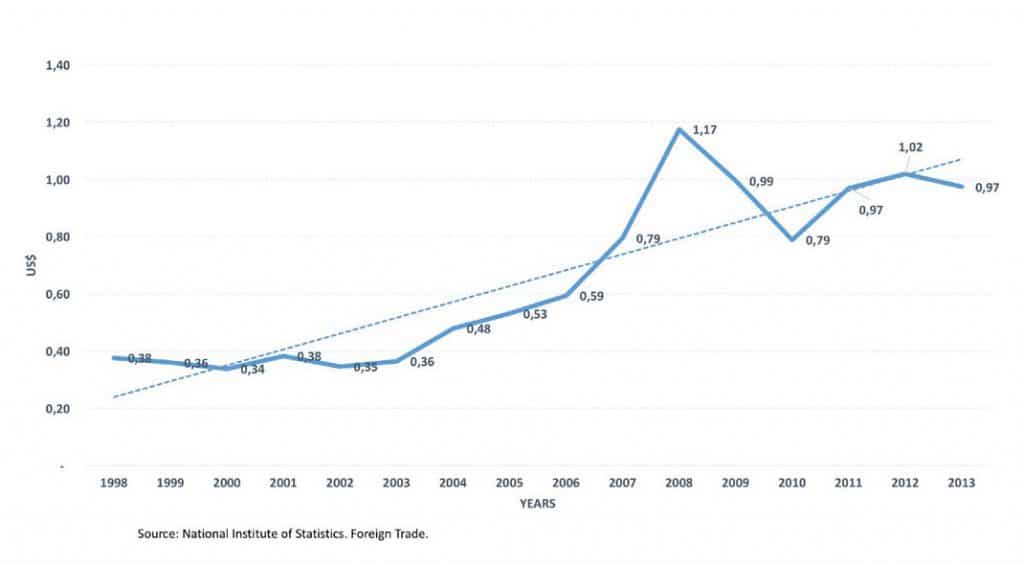

The average cost per kilogram of imported food jumped by 167%, from USD 0.36/kg in 2003 to USD 0.97/kg in 2013. Chart 13 shows the behaviour of the average cost of food from 1998 to 2013.

Chart 13. Cost per kilogram of imported food products, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 1998–2013

From this analysis it is possible to draw the following conclusion: among the factors associated with shortages, imports of goods and services, measured in kilograms, did not increased enough to meet demand. However, this was not because the government failed to deliver enough foreign exchange to the private sector—the necessary amounts have actually been delivered, as demonstrated above. In fact, with a higher amount of foreign exchange delivered private companies have imported less goods (by weight). The fact that the increase in dollar-denominated imports is proportionally much higher than that of imports expressed in kilograms, thus recording an increase in the average cost per kilogram imported, coupled with the increase in the foreign exchange allocations to the private sector on the one hand, and the increase of shortage rates on the other hand, matches the upwards behaviour of the private sector currency and deposits abroad.

Chart 14 shows the trend of the variable “foreign exchange and deposits by the private sector abroad” from 1997 through 2013. Crucially, such deposits increased by approximately 232.8% between 2003 and 2013.15

Chart 14. Foreign exchange and deposits of the private sector abroad, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 1997–2013

The private sector practice of siphoning off foreign exchange delivered by the government into deposits abroad represents a failure to comply with the purpose of such allocations (i.e., the import of goods and services). This is precisely why the government has repeatedly denounced the hoarding of goods by private suppliers of food, medicines and personal care products, as well as parts and car spare parts.

Hoarding is a mechanism that prevents goods from reaching the shelves of domestic markets, thus adding a factor to the explanation of shortages. It is important to draw attention to the characteristics of the goods that have been the subject of hoarding. These are, first of all, prime necessities, food, medicines, personal and household hygiene goods, car spare parts, spare parts for machinery and seeds. That is to say, they are goods very much needed in the households or in the manufacturing of goods or the performance of services.

Secondly, as far as food is concerned, of the twenty food products mostly consumed by Venezuelans, shortages have been observed primarily for nonperishable items, especially those produced and distributed by monopolistic or oligopolistic corporations (for example corn and wheat flour, sugar, coffee, oil); but not for goods produced and distributed by many farmers (for example, fruits and vegetables). This led us to hypothesize that the cost of agreements between production and distribution companies to control the supply is less when it comes to one or a few companies than when there are many producers and distributors.

Thirdly, shortages have been observed primarily within retail sector. The shortage of these goods for industrial or commercial use has been much less significant. For example, bakery stores have had access to wheat flour but it remains being absent in supermarkets.

Further, the Government has denounced smuggling, mainly to Colombia, to the extent that the border check-points with that country have been closed as a measure to stop the massive exit of Venezuelan products to this neighbouring country. Shortages are also connected with such smuggling.

Three factors—1) the relative decrease of imports with respect to the foreign exchange delivered to the private sector; 2) hoarding by oligopolistic companies that dominate the markets of some goods; and 3) smuggling—in that order, are determinants explaining the level of shortages in Venezuela.

Although they seem to be factors based on economic interests seeking to maximize profits, and even worse in the case of the Venezuelan economy, to seize oil revenues, they imply a predominantly political interest. This conclusion is supported by the observation that the episodes of shortages coincided with moments of political tension, greater polarization and in the context of electoral events.

Such political interest, as repeatedly denounced by the government, seeks to generate economic, social and political destabilization, and to promote the idea that the model established in 1999 has failed; at the same time the tactic allows the destabilizing sectors to obtain economic profit—unlike in 2002, when the call for a general strike with similar political objectives involved large economic losses, not only for the nation, but also for these sectors.

As a conclusion of this first section we must point out: 1) shortage in Venezuela is not explained by declines in production or in imports resulting from a failed model that has not allocated foreign exchange to the private sector; 2) on the contrary, the amount of foreign exchange delivered to the private sector has increased, along with production; 3) the real reasons for shortages in Venezuela are (in order severity): a) the decrease in imports despite having delivered the necessary foreign exchange to the private sector; b) the selective hoarding of goods to meet prime necessities; and c) smuggling.

The main recommendation that emerges from this analysis is the urgent need to establish greater controls on the delivery of foreign exchange to the private sector and to revise the criteria for the allocation of dollars, especially when we are faced with a drop in oil prices and, therefore, a decline in national income.

In this regard, it is important to note that codes for the allocation of foreign exchange, as well as the “non-production certificate” criteria, should be revised; foreign exchange should be allocated based on the main requirements of Venezuelans, rather than a non-production certificate.

In addition, it is necessary to strictly supervise the goods that are actually imported and distributed with the foreign exchange delivered for such purposes.

The recommendations should always be aimed at structural measures, at strengthening national production with production models that promote socially owned enterprises as well as institutionalizing processes to prevent a few large companies from seizing the oil revenues through the allocation of foreign exchange.

Notes

- ↩ Based on the paper “Desabastecimiento e Inflación” completed on 20 December 2015 and available in the web page of the Institute of Advanced Studies (IDEA in Spanish).

- ↩ These questions are intended to answer the economic theory as far as the study of the behaviour of a particular economy is concerned. The main variables showing the behaviour and trends of the economy, subject in the study of macroeconomics, are production, employment and prices. Such variables indicate the economic situation.

- ↩ According to the economic theory, inflation in a given economy is explained or determined by aggregate demand, that is to say, as the aggregate demand increases, the price index increases in the short term. This thesis supports the Keynesian school. On the other hand, the monetarist school explains the price levels for the behaviour of monetary liquidity, i.e. an increase in monetary liquidity will imply price increases. In any case, and for the purpose of this study, increases in monetary liquidity means increases in aggregate demand and these into prices. What we highlight is the fact that according to economic theory, either aggregate demand or monetary liquidity affects prices.

- ↩ We ask this question in order to measure whether the exchange rate of the so-called “parallel currency market” is being the reference for fixing the prices in the real economy, beyond the behaviour of aggregate demand and liquidity.

- ↩ The theory also states that the levels of the exchange rate of a given currency are based on and supported by the levels of its international reserves and, therefore, its behaviour over time. To the extent that international reserves decline, this would imply an increase in the exchange rate, i.e., currency depreciation.

- ↩ Provided it is a “normal good”—normal goods are those for which demand increases when the consumer’s income increases. Inferior goods are those for which demand decreases when consumer income rises.

- ↩ When items such as diapers are not be available because the government has not granted dollars to importing companies, this results in buyers of diapers demanding more diapers to stock for some time due to the effect on expectations. The same happens with long life items, such as [powdered] milk, flour, toiletries and all basic non-perishable necessities that may be preserved over long periods of time.

- ↩ Latest figures included by BCV and INE in the report titled “Indice nacional de precios al consumidor en los meses de noviembre y diciembre 2013” available from the Venezuela Central Bank.

- ↩ From the above mentioned report.

- ↩ The official figures we handled are until 2013.

- ↩ Corresponds to Sections I: Live animals and products from the animal kingdom; II: Vegetable products; III: Animal or vegetable fats and oils; Products of their unfolding; Processed fats; Waxes of animal or vegetable origin and IV: Products of the food industry; drinks; Liquor and vinegar; Tobacco and manufactured tobacco substitutes, from the classification for imports. This information was taken from the website of the National Statistics Institute.

- ↩ In fact, the Pearson correlation coefficient, measured between the scarcity index and food imports for the period 2003-2013 is 0.624 with a significance of 0.05. This means, firstly, that the relationship is direct and positive, when imports increase, scarcity increases, and also at relatively high levels, i.e. a 62.4% increase in food imports corresponds to an increase of 62.4% of shortage.

- ↩ There is a direct and positive relation between the foreign exchange delivered to the private sector and total imports. The Pearson correlation coefficient between the two variables for the period 2003-2013 is 0.752, significant at 0.01.

- ↩ While the slope of the consumption trend is 5.07, that of the trend that shows the sum of what is produced plus imports is 5.99. That is, what it has been produced and imported, measured in Bolivars, on average, has been higher than what it has been consumed over that period.

- ↩ By correlating “foreign currencies and deposits by the private sector” with “average cost of imported goods” variables for the period 1997 to 2013, we obtained a Pearson coefficient equal to 0.712, significant to 0.01. That is, an increase in the average cost of imported goods with 71.2% corresponding to an increase in the deposits of the private sector abroad. A similar statistical analysis of average cost of imported foods yielded a Pearson coefficient equal to 0.747, significant to 0.01.