As of July 2017, the Bank of England measured the stock of private debt held by individuals at £1.548 trillion; making household sector indebtedness one of the biggest problems facing the United Kingdom’s economy and society. There is growing public policy concern over the historically unprecedented level of household debt but little by way of proposed solutions to deal with it. Is this level of private household debt a problem requiring action by an incoming Labour government? Can public policy address the unprecedented levels of household debt?

Analysis

1. Current high household debt levels are the result of over two decades of promoting finance-led growth, in which stagnant wage growth combined with easy credit to fuel asset bubbles and drive consumer demand.

Finance-led growth refers to the shifting patterns of accumulation from productive to financial activities since the 1980s. In Britain the macroeconomic model is simple: low-interest rates, private debt, domestic demand, asset-markets and consumption coalesced to produce a period of stable growth. The 2008 global finance crisis exposed the fragile balancing act required to manage finance-led growth. The basic contradiction lies in rapidly growing private debt stock and stagnating income flows.

The simplicity of the finance-led growth model is also its fundamental fragility: private debt generates demand which would not otherwise be there. This demand drives up property prices and fuels consumer spending through more indebtedness and persistently stagnant wage incomes.

Understanding how finance-led growth operates requires recognizing that banks create money by opening debt deposit accounts when new loan contracts are issued. The ‘originate and distribute’ retail banking business model, which caused the 2008 financial crisis, remains largely unchanged. Efforts since the crisis to replenish capital reserves and focus on macro-prudential regulation have not changed how money is created in the British economy: new loans are issued and money is created. Banks then take these thousands of new contracts, bundle together and re-sell them multiple times across global financial markets. The original debt and all subsequent claims to the interest payments on that debt are wholly dependent on current incomes of households to keep up repayments.

2. Size and scope of the household debt is an economic and societal problem, but with little recognition at the public policy level.

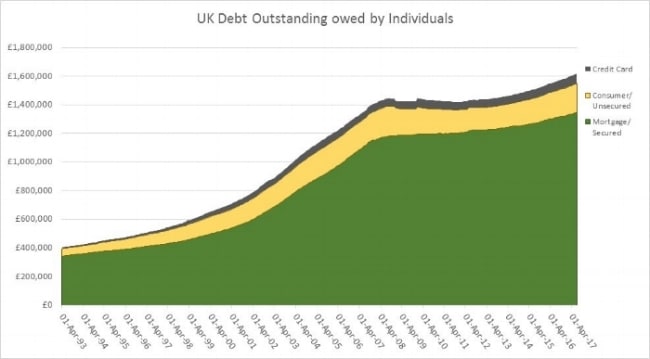

Figure One – Stock of Debt held by Household Sector 1993-2017. Source: Bank of England, Millions £, Seasonally Adjusted, Series: LPMVTXK, LPMBI2O, LPMVZRJ

Figure one shows the total stock of debt owed by the household sector, £1.545 trillion, of which 86% was mortgage debt (£1.344 trillion). Public policy has promoted home ownership as a means of ‘asset-based welfare’. Households are presumed to first accumulate saving in the value of their primary residence, which as they grow older provides a cash reserve at times of need and income flow for retirement. These assumptions largely ignore that residential property has become a highly-leveraged form of investment because house price increases are fuelled by cheap credit.

Housing price appreciation is unequally distributed across the household sector, going primarily to the older age demographics, and those living in the London and the South East. This geographic concentration fuels already pronounced trends in income inequality. More problematically, the large debt now required to buy housing by the younger households, plus the rapid growth in home equity loans taken out by retired homeowners complicates the assumption that homeownership offers a meaningful welfare provision.

According to the Bank of England, consumer debt is also at an all-time high of £201.5 billion, with credit card debt at £68.7 billion. In the past year, outstanding car loans, credit card balance transfers and personal loans have increased by 10%, while household incomes have risen by only 1.5%. Too often consumer debt is considered the product of profligate spending. It is more appropriately seen as the engine of consumer demand and a major profit centre for the retail banking industry. Persistently stagnant wages, especially since 2008 when a growing number of households experienced real wage decline, and rising consumer debt suggest access to debt is the dominant source of consumer demand in the UK economy. The average total debt per household, including mortgages, is £57,005 which is approximately 113.8% of average earnings.

More troubling is the emerging trend of households using debt as a safety-net to cope with unemployment, illness or one-off emergency. The cost of emergency borrowing varies drastically by income and wealth decile; the better off can access cheap credit by borrowing against the equity in their homes, those without home equity can access lines of credit or credit cards, while the lowest income groups use payday and other fringe financial lenders.

As the cost-of-living crisis becomes more pervasive, households are increasingly turning to debt to simply meet basic household cash flow needs. According to the debt charity StepChange, debt is increasingly being used to cover essential expenses like rent/mortgage, council tax, electricity.

Britain’s household debt overhang places a significant drag on growth, because households use current income to pay down debts rather than to spend or invest. This is the basic mechanism of a “balance sheet recession”. Almost 10 years after the financial sector received its first bailout, most of the household sector continues to struggle to repay the stock of debt accrued during the boom years. As present-day income of wage earners is used to make interest repayments on outstanding debt, it creates a drag on economic renewal. For example, in the 12-month period from July 2017, approximately £50.149 billion or an average of £137 million per day is diverted to banks to service the outstanding debt stock.

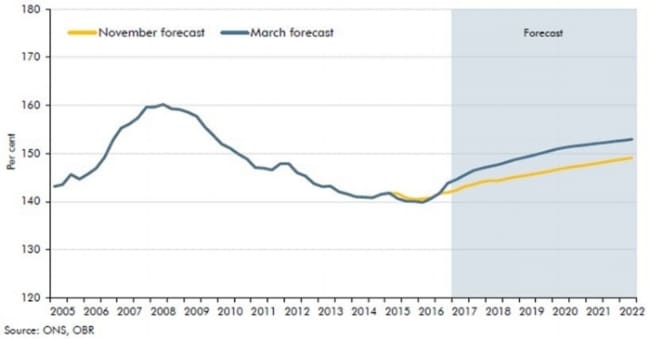

UK public policy commitments to ‘austerity’ compound the problem by advocating the simultaneous de-leveraging (paying down debts) of both the public and private sectors. Large scale cuts to government income transfers and social security, without any attempt at fiscal stimulus to promote wage growth or more stable employment essentially shift the costs of economic recovery on the household sector using private debt. UK economic policy is so dependent on private debt that the Office for Budget Responsibilities regularly predicates the UK’s future growth predicated on rising household debt level.

The problems caused by household-level private debt are manifest across the economy and are not reducible to individual choice or responsibility. The economy as a whole is dependent on household debt to grow, in the same way households are dependent on debt to maintain living-standards. However, without wage growth, stable employment or a social safety-net, the household sector’s ability to sustain the national private debt stock is not clear. If every household struggling with debt decided to pay down their debts the national economy would be plunged into depression.

However, if households struggling with debt continue to take on more debt to maintain their standard-of-living, soon there will be rising insolvency rates. Currently, most households keep up their debt repayments and regularly remit a growing portion of their current income to pay for all past expenditures. If for whatever reason households are unable to make these regular repayments a worse scenario unfolds in which default rates add to the portfolio of non-performing loans on banks’ balance sheets. As the 2008 financial crisis revealed, the elaborate network of financial claims flowing through the global financial system are vulnerable to default on even small-scale household-level loans (US sub-prime mortgages). Rising default rates in the household sector would, once again, start letting off sparks that could set off another firestorm across global markets.

Policy Framework

Analysis of the scale and scope of private debt in the UK shows that it is unsustainable to rely on the household sector to fuel macroeconomic growth by taking on ever-more levels of debt. Continuing to ignore household indebtedness as a public policy issue is reckless. Potential policies are:

- Make cheap credit a public good. Banks enjoy access to credit at negative real interest rates, the base rate is 0.25% (the lowest ever recorded) and inflation is 2.9%. At the same time, the household sector pays for credit on a sliding scale from 2% – 4.5% for residential mortgages; 3.5-6.5% on consumer loans, 16-19% on credit cards and well over 500% on fringe financial products. As taxpayers that underwrite the entire financial system, the household sector deserves access to the same cheap credit enjoyed by banks.

- UK’s residential housing market needs to be de-leveraged to become affordable, more equitable, and sustainable over the long term. Housing does not provide a reliable and consistent source of saving, and, therefore, the credit-asset bubble needs to be deflated before it explodes. One potential way of doing this would be to offer a Long-term Refinancing Operation, LTRO for homeowners, in which highly leveraged primary residence, whether first lien or home equity second lien mortgages, could access refinancing terms that balance future equity gains with present day debt relief.

- Household sector income growth and employment markets that generate wage gains are necessary to abate the household sector’s and public policy’s dependence on debt to sustain living standards and drive economic growth. However, without debt restructuring or relief for households any income gains will be diverted directly into the financial system over the medium-term as households seek to pay-off their debts.

- A Labour government should implement a coordinated and comprehensive plan for household debt restructuring and relief would offer the most direct route to ending the fragile finance-driven growth model and providing stimulus directly to the household sector.

Johnna Montgomerie is Senior Lecturer in Economics and Deputy Director, Political Economy Research Centre at Goldsmiths College.