Google—the advertising and search engine monolith that once touted its official commitment, “Don’t be evil”—has thrown its full weight behind the U.S. military-industrial complex’s fast-advancing unmanned drone program – and more than three thousand of its employees will have none of it.

In a letter to Google CEO Sundar Pichai, over 3,100 employees invoked the now-discarded slogan in an appeal demanding that the company not allow its artificial intelligence technology to be used to improve the targeting capabilities of the United States’ deadly drone fleet. Google’s Project Maven is an AI surveillance engine that uses footage captured by the U.S. Armed Forces’ unmanned aerial vehicles to detect and track objects such as vehicles, while combing through, organizing, and feeding the processed data to the Pentagon.

Watch | Project Maven: The Pentagon’s New Artificial Intelligence

https://youtu.be/5UfF121mFiQ

The letter, which is fast making the rounds on Google campuses and internal communication servers, demands the cancellation of the project and the public adoption of a policy pledging that neither Google nor its contractors produce technology for warfare. The letter states:

This plan will irreparably damage Google’s brand and its ability to compete for talent. Amid growing fears of biased and weaponized AI, Google is already struggling to keep the public’s trust. By entering into this contract, Google will join the ranks of companies like Palantir, Raytheon, and General Dynamics. The argument that other firms, like Microsoft and Amazon, are also participating doesn’t make this any less risky for Google. Google’s unique history, its motto Don’t Be Evil, and its direct reach into the lives of billions of users set it apart.

However, journalist and author Yasha Levine has explained in his new book Surveillance Valley: The Secret Military History of the Internet that Google long been a leading Silicon Valley vendor to the U.S. repressive state:

Over the years, [Google] supplied mapping technology used by the U.S. Army in Iraq, hosted data for the Central Intelligence Agency, indexed the National Security Agency’s vast intelligence databases, built military robots, co-launched a spy satellite with the Pentagon, and leased its cloud computing platform to help police departments predict crime. And Google is not alone. From Amazon to eBay to Facebook … Some parts of these companies are so thoroughly intertwined with America’s security services that it is hard to tell where they end and the U.S. government begins.

The grim calculus of remote-controlled warfare

An Air Force RPA reconnaissance drone is retrofitted for use in attack squadron. (Photo: U.S. Air Force)

Thousands of alleged “combatants” have been killed in U.S. drone strikes since the start of the post-9/11 “War on Terror.” Former President Barack Obama ramped up the targeted killing program using drones in 2009, pledging that the use of unmanned aerial platforms was part of a “just war—a war waged proportionally, in last resort, and in self-defense.”

Reports have shown that the use of drones in such locales as Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Syria, Yemen and other theaters of operations have claimed a vast number of civilian lives—over 15,000 in 2017, according to surveys. According to New York Times Magazine, which surveyed 150 Coalition drone strikes carried out in Iraq over an 18-month period, one out of every five strikes kills civilians.

Watch | Suffering in Silence: a documentary about the war on terror in Pakistan

The American Civil Liberties Union has denounced the use of such tactics as contrary to international law:

A program of targeted killing far from any battlefield, without charge or trial … violates international law, under which lethal force may be used outside armed conflict zones only as a last resort to prevent imminent threats, when non-lethal means are not available.

There is very little information available to the public about the U.S. targeting of people far from any battlefield, so we don’t know when, where and against whom targeted killing can be authorized … The secrecy and lack of standards for sentencing people to death, resulting in a startling lack of oversight and safeguards, is one of our prime concerns with this program.

In 2007 at the height of George W. Bush’s “troop surge” in Iraq, Google enlisted in the “Global War on Terror” in a discrete partnership with Lockheed Martin. While enhanced versions of Google Earth were already at the disposal of government agencies, the tech firmed helped to design a Google Earth product for the Pentagon’s National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency that displayed a visual representation of U.S. and Iraqi military bases in Iraq as well as the location of Sunni and Shiite neighborhoods in Baghdad, allowing occupation forces to oversee and manage the bloody fratricidal warfare between the groups as well as the possible location of insurgent organizations within their ranks.

It was during this same year that the development and use of Air Force drones in the Iraqi quagmire dramatically increased, nearly doubling between January and October of 2007.

Google defends its public image (and low-profile military ties)

Eric Schmidt, then-executive chairman of Alphabet, speaks at a press conference at the Google DeepMind Challenge in Seoul, South Korea, March 8, 2016. (AP/Lee Jin-man)

Claiming that it values the input of its employees as an “important part” of its company culture, Google has promised to address the AI-drone issue without making specific comments on the employees’ demands. In a statement Tuesday, the company said:

Any military use of machine learning naturally raises valid concerns. We’re actively engaged across the company in a comprehensive discussion of this important topic and also with outside experts, as we continue to develop our policies around the development and use of our machine learning technologies.

Google has also defended its participation in the Pentagon program with the claim that its usage is specifically for non-offensive purposes and uses open-source object-recognition software based on non-classified data that’s freely available to any users of the Google Cloud, and could in fact save lives while saving labor through the use of AI.

Google’s own top corporate chiefs are quite close to the Pentagon: Google vice president Milo Medin serves on the Department of Defense’s tech advisory body, the Defense Innovation Board, which is also chaired by former Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt, who remains an executive board member at Google’s parent company, Alphabet Inc.

Google itself has long been interested in developing its own line of drone products, including private delivery drones.

The company is also a leader in AI and machine-learning technology. Its subsidiary DeepMind Technologies, Inc. has recently developed a program based on Google Street View that allows AI-based platforms to take part in long-range navigation and cross complicated urban environments. The navigator AI system is capable of steering everything from autonomous, self-driving cars to robotic vacuums and even unmanned drones.

Watch | Eric Schmidt at the Artificial Intelligence and Global Security Summit

Last November in a keynote address on artificial intelligence in warfare before Washington-based think-tank the Center for a New American Security, Schmidt pinned anxiety about his company’s acquisition of DeepMind on “a general concern in the tech community of somehow the military-industrial complex using their stuff to kill people incorrectly, if you will.”

“It comes from a, it’s essentially related to the history of the Vietnam War and the founding of the tech industry,” Schmidt added.

That Google helps the military build more efficient systems of surveillance and death shouldn’t be surprising. The company has spent the last 15 years selling souped-up versions of its information technology to mil and intel agencies.https://t.co/8UfdiGVeqc

— Yasha Levine (@yashalevine) March 16, 2018

Indeed, Levine argues:

In the 1960s, America was a global power overseeing an increasingly volatile world: conflicts and regional insurgencies against U.S.-allied governments from South America to Southeast Asia and the Middle East. These were not traditional wars that involved big armies but guerrilla campaigns and local rebellions, frequently fought in regions where Americans had little previous experience. Who were these people? Why were they rebelling? What could be done to stop them? In military circles, it was believed that these questions were of vital importance to America’s pacification efforts, and some argued that the only effective way to answer them was to develop and leverage computer-aided information technology.

Surveillance capitalism’s military-industrial roots

Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole of Kansas, right, and House Speaker Newt Gingrich of Ga., with the help of “Ben Franklin,” introduce the first conservative Internet community “Town Hall,” in Washington on June 29, 1995. ‘Town Hall” was a joint venture of the Heritage Foundation and the National Review Magazine. (AP/Mark Wilson)

In a 2014 essay for Monthly Review magazine titled “Surveillance Capitalism: Monopoly-Finance Capital, the Military-Industrial Complex, and the Digital Age,” authors John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney coined the phrase surveillance capitalism, tracing its origins to the inception of a post-World War II “new Pentagon capitalism” that came to be known as the military-industrial complex.

Under the model – revolutionized by then-Army Chief of Staff and later President Dwight D. Eisenhower – the U.S. technological, scientific research and industrial capacity were to become “organic parts of our military structure” in conditions of national emergency, effectively giving the civilian economy a dual-use purpose. In a 1946 memorandum, Eisenhower noted:

The future security of the nation … demands that all those civilian resources which by conversion or redirection constitute our main support in time of emergency be associated closely with the activities of the Army in time of peace.

The model became a permanent feature of the U.S. economy, giving birth to a sprawling military-civilian economic base Eisenhower famously criticized in his 1961 farewell address to the nation. Civilian industry, science, and academia were used alongside an exorbitant and perpetually-expanding war budget to underwrite the Defense Department’s never-ending state of conflict with Cold War enemies and unruly populations, making the world safe for the unchallenged reign of U.S. monopoly capitalism (imperialism) and “pump-priming” the economy whenever an additional surge of “military Keynesian” government spending was required.

Watch | Richard Wolff On Trump’s Defence Spending

According to the popular history of the internet’s origin, it was conceived in 1969 by scientists at the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), who sought to create a means of “internetworking” Pentagon-sponsored computer mainframes belonging to government agencies, universities and defense contractors across the United States and NATO bloc. Known as Arpanet, the decentralized system allowed for military nodes – down to a battlefield level – to network and share data quickly and wirelessly. In the event of a nuclear strike or major war where swathes of the network were destroyed, the Arpanet would remain operational.

Levine posits that a primary purpose of conceiving the “information superhighway” was the need for a computerized counterinsurgency tool that could predict and check the “perceived global spread of communism” and provide real-time surveillance of potential threat groups:

The Internet came out of this effort: an attempt to build computer systems that could collect and share intelligence, watch the world in real time, and study and analyze people and political movements with the ultimate goal of predicting and preventing social upheaval. Some even dreamed of creating a sort of early warning radar for human societies: a networked computer system that watched for social and political threats and intercepted them in much the same way that traditional radar did for hostile aircraft. In other words, the Internet was hardwired to be a surveillance tool from the start. No matter what we use the network for today—dating, directions, encrypted chat, email, or just reading the news—it always had a dual-use nature rooted in intelligence gathering and war.

The Arpanet system formed the backbone of U.S. military communications from 1969 until 1989, when the World Wide Web was introduced to civilian consumers. The unveiling of the World Wide Web opened the floodgates to the use of the internet by users across the globe, as well as its subsequent commercialization and the resulting dot com boom of the mid-to-late 1990s, when Google was founded.

Watch | Yasha Levine on why we lost our fear of computers as tools of social control

The rapid advance of digital technology has ensured that the U.S. economy—and social life itself—is now dominated by big-data giants like Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon (GAFA), as well as Microsoft, Intel, Cisco Systems, IBM and Hewlett-Packard. This new technology-dominated market environment, where private user info is parsed, monetized, packaged and sold, has been encapsulated by the well-worn cliché: “data is the new gold.”

Vast strides in biometrics, analytics research, AI, and deep-learning technology – perfected not only by Google but by academic researchers and technology firms across the globe – have vastly boosted the state’s ability to surveil and control populations and police dissent across the globe. Many of the technologies developed by global arms, surveillance, and data-analysis firms are supplied to countries requiring tailor-made solutions to unrest such as India, China, Myanmar, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bahrain, and Azerbaijan.

The extent of Silicon Valley’s integration with the U.S. government was laid bare to the public in 2013, when Edward Snowden provided evidence proving that the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had direct access to the internal servers of nine major tech firms – AOL, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, PalTalk, Skype, YouTube, and Yahoo – each of which provided direct access through major internet service providers to the NSA through its secret projects like Boundless Informant and Prism.

Foster and McChesney explained:

These monopolistic corporate entities readily cooperate with the repressive arm of the state in the form of its military, intelligence, and police functions. The result is to enhance enormously the secret national security state, relative to the government as a whole.

Edward Snowden’s revelations of the NSA’s Prism program, together with other leaks, have shown a pattern of a tight interweaving of the military with giant computer-Internet corporations, creating what has been called a ‘military-digital complex.’ Indeed, Beatrice Edwards, the executive director of the Government Accountability Project, argues that what has emerged is a ‘government-corporate surveillance complex’.

Information superiority and the modern battlefield

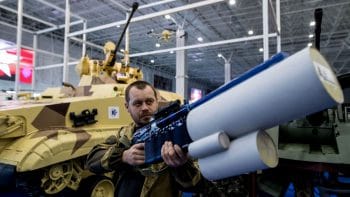

A portable complex of radio and optical-electronic suppression of unmanned aerial vehicles at the Robotization of the Russian Armed Forces 2nd Military & Scientific Conference. (Iliya Pitalev/Sputnik via AP)

At present, the digitalization of the military-industrial complex gives the United States a commanding edge in terms of military technology and high-tech warfare, which is augmented by optical spy satellites capable of capturing remarkably detailed ground-level imagery, successive generations of wireless networking technologies, pattern-recognition and machine-learning systems, and unmanned warfighting platforms.

As a matter of survival, however, all modern militaries – both regular and irregular, large and small – are being forced to adapt to the digitization of warfare.China, Russia, and even non-state actors like Lebanese resistance group Hezbollah are fast making technological advances to keep pace in the informationized battlefield.

The weaponized nature of digital technology is a pandora’s box that may prove impossible to close. Be that as it may, Google’s employees are livid about their participation in these developments:

We cannot outsource the moral responsibility of our technologies to third parties … Building this technology to assist the U.S. Government in military surveillance – and potentially lethal outcomes – is not acceptable.

While the tech conglomerate workers’ attempt to decouple Google from the Pentagon may be in vain, one can only applaud their efforts to protest the tech conglomerate’s complicity in the bloodshed wrought by U.S. imperialism through its array of increasingly high-tech implements of death.