Trump’s trade tirades are being vigorously disputed by liberal economists the world over, although the riposte is usually in defence of free trade and existing trade deals. However, many of these same economists have promulgated the underlying idea that U.S. trade deficits are the result of some sort of disadvantage or decline.

For instance, as I discussed in 2009, 2010, 2011 and 2012, many prominent economists such as Paul Krugman argued then (and many still do now) that China’s undervalued currency gave it an unfair advantage, causing deficits and even financial bubbles in the U.S. Many economists on the left have taken a similar line of argument. For instance, Yanis Varoufakis argues that U.S. trade deficits have planted the seeds for the downfall of the U.S. ‘Minotaur’ because it has made the country increasingly dependent on the willingness of other countries to finance these deficits.

Beyond methodological nationalism

The problem with this reasoning is that international trade, income and financial data mostly represent the trade, income and asset movements made by corporations. Conversely, our system of international accounts is severely out of date given that these data are still reported on the basis of country residence rather than ownership. It also treats these flows as if they were arm’s length trades in final goods, or so-called ‘autonomous’ flows of income or finance, rather than the internalised operations of lead firms and their networks of subsidiaries, affiliates, or subcontractors.

The country-based framing of the international accounts serves to obscure the very resilient and virulent foundations of U.S. power, based in the private corporate sector. Corporate ownership and/or control of trade, income and financial flows have become increasingly internationalised, even while remaining predominantly centred in the North and with a strong allegiance to maintaining U.S. dominance. International efforts to track and govern these aspects of ownership or control from the 1970s onwards have also been systematically undermined, especially by the U.S. As a result, the antiquated international accounting system is very unfit for the task of tracking these corporate activities. Most of the discussion on global imbalances avoids this reality.

In this sense, as argued by Jan Kregel already a decade ago, the U.S. shift to systemic trade deficits from the late 1970s onward is best understood as a reflection of this internationalisation of U.S.-centred corporations as well as the increased profitability of these U.S. corporations operating in the international economy.

A simple stylised example is the iPhone. When Apple sends a production order to a subcontractor, this is not recorded as a service export from the U.S. However, the return export of the iPhone is reported as a goods export from China, even though the export is contracted by Apple, a U.S. company. The iPhone is then sold in the U.S. at many times its exported value, and the vast majority of the value of the final sale is accrued in the U.S. The U.S. has a merchandise trade deficit in this production and distribution network, even though this deficit is associated with the immense value-added accrued in the U.S. and the profitability of Apple. The same applies when Walmart exports from itself in China to itself in the U.S.

The idea that China’s surpluses and foreign exchange reserves constitute increasing power is similarly based on this flawed understanding of international accounts. As I have argued in 2010 and 2015, a rarely acknowledged attribute of the explosion of China’s surpluses in the 2000s was their rapid denationalisation. Foreign funded enterprises (FFEs)—most fully foreign funded—quickly came to dominate the exports of China, and then the trade surpluses themselves, to the extent that by 2011, FFEs accounted for over 84% of the merchandise trade surplus.

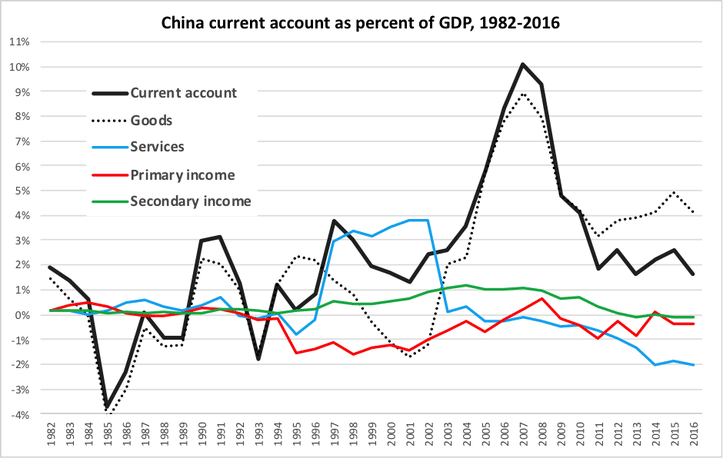

This share subsequently fell sharply due to a surge in exports from non-FFEs, although this was also in a context of falling current account surpluses as a proportion of GDP. As shown in the figure below, this was due to increasing deficits on China’s services account, which reached 2% of China’s GDP in 2014-16, knocking out about half of its goods surplus in 2014 and 2016.

China also returned to running deficits on its income account from 2009 onwards (with the slight exception of 2014), despite being a major international creditor. As explained by Yu Yongding, this is because China’s foreign assets mostly earn very low returns, such as in U.S. treasury bills, whereas foreign investment in China is very profitable, possibly in excess of 20-30% per year, thereby cancelling out any of the balance of payments benefits that would normally accrue to being a major international creditor.

Source: Author’s calculations from IMF balance of payments and international finance statistics (last accessed 21 March 2018).

Notably, the U.S. is the mirror image of China: it is a major international debtor and yet it earns a surplus on its income account. Both situations were due to profit remittances, e.g. profits leaving China and entering the U.S. Indeed, Yilmaz Akyüz estimates that the net current account position of FFEs in China has been in deficit in recent years, meaning that their profit remittances were cancelling out their merchandise trade surpluses.

In other words, after the exceptional but historically brief period of running very large ‘twin surpluses’ (on both the current and financial accounts), the current account structure of China has reverted to a pattern that, as I explain in a recent article, is common among peripheral developing countries. The pattern is characterised by goods trade surpluses that counterbalance service account deficits (dominated by payments to foreign corporations) as well as the profit remittances of foreign corporations (and of other foreign investments, whether licit or illicit).

These rapid transformations have been reflective of the increasingly deep integration of China’s foreign trade into international networks dominated by Northern-based transnational corporations. The model has resulted in exceptional export performance, although this has occurred through the injection of considerable but underappreciated sources of vulnerability.

Indeed, as noted by Yu Yongding, from 2015 to 2017 the People’s Bank of China undertook the largest intervention in foreign exchange markets that any central bank has ever taken in order to prevent a run on the renminbi. This depleted its foreign exchange reserves by over 1 trillion U.S. dollars. In another recent article, Yu adds that from 2011 to 2017, around 1.3 trillion U.S. dollars of China’s foreign assets had effectively disappeared, probably reflecting capital flight. Together with the run on the renminbi, these were the principal reasons that the Bank of China put a hold on capital account liberalisation and tightened capital controls to an extent not seen since the East Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s.

Considering that much of such capital flight is destined for the U.S., either directly or indirectly via multiple offshore financial centres, in addition to the profitability that U.S. corporations derive from China’s trade with the U.S., it is clear that the U.S. is in the more powerful position in this bilateral relationship.

The imperial utility of trade decline discourses

From this perspective, the deep U.S. trade deficits that have persisted since the early 1980s arguably represent a new form of advanced capitalist imperialism, the emergence of a system of tributes whereby states around the world effectively subsidise the expansion of U.S.-centred capitalism. At the very least, the deficits are signs of a structural shift underlying global power relations, based on an increasingly predatory form of financialised capitalism, with the U.S. still at its helm.

Much like with discourses of Soviet rivalry in the 1960s and 1970s, the current babble of U.S. decline and lagging serve an ideological purpose within these continuing transmutations of U.S.-centered power. It is effectively aimed at subordinating other countries and shifting the burden of adjustment onto them, while distracting attention away from the U.S.-centered, corporate-led restructurings of global production systems that underlie U.S. deficits in the first place.