Liberals like to talk about all kinds of social ills and identity-laden tensions—but not class struggle. That’s their persistent and enduring blindspot.

Except, it seems, when it comes to Donald Trump.

Thomas B. Edsall is a good example. Over the years, he’s produced a series of solid, insightful surveys of liberal research and analysis on a wide variety of economic and political topics. But he hasn’t written much if anything about class—until his latest, titled “The Class Struggle According to Donald Trump.”

And, to give him credit, Edsall is right about one thing:

Trump campaigned as the ally of the white working class, but any notion that he would take its side as it faces off against employers is a gross misjudgment.

But his view of class struggle is sorely lacking. First, Edsall starts with and highlights the recent work of Alan Krueger and Eric Posner, who criticize “labor market collusion” on the part of large employers and maintain that the ideal labor market is one in which “workers can move freely to seek the most desirable opportunities for which they are qualified.”

Presumably, if the appropriate reforms were made—for example, scrutinizing mergers for adverse labor market effects, banning non-compete covenants that bind low-wage workers, and no-poaching arrangements among establishments that belong to a single franchise—the problem of class struggle would be solved.

Second, Edsall accepts the idea that, until the 1970s, class struggle in the United States had mostly disappeared or held in abeyance, under the “postwar capital-labor accord.” But there never was such an accord—or, as it is sometimes referred to, a “truce.”

As economists Richard McIntyre and Michael Hillard (unfortunately behind a paywall) have argued,

Recent U.S. historical and industrial relations scholarship rejects the existence of such an accord. . .The existence or non-existence of an accord is not only an important matter of history; it has very definite practical effects. During the 1980s and 1990s especially, many in the labor movement and some radical economists sought “cooperation” between capital and labor as a cure for the ills of the American economy, often harkening back to the imagined “golden age.” But if such cooperation is a historical chimera, the time and energy put into “cooperation” might have been better spent in the self-organization of the working class.

Today, under Trump, Edsall and other liberals are attempting to revive that tradition, hoping that reforming the labor market can serve as the basis for more “cooperation” between capital and labor.

Ironically, both Trump and liberal thinkers like Edsall invoke a nostalgia for the exact same postwar period. In the case of Trump, it was a time when U.S. manufacturing successfully exported to the entire world; for Edsall and company, it’s when labor and capital agreed to cooperate and negotiate peacefully.

But that doesn’t mean there wasn’t intense class struggle during that period—or, for that matter, afterward. Only that the conditions and consequences have changed. And employers have been on the winning side for decades now, long before Trump was elected.

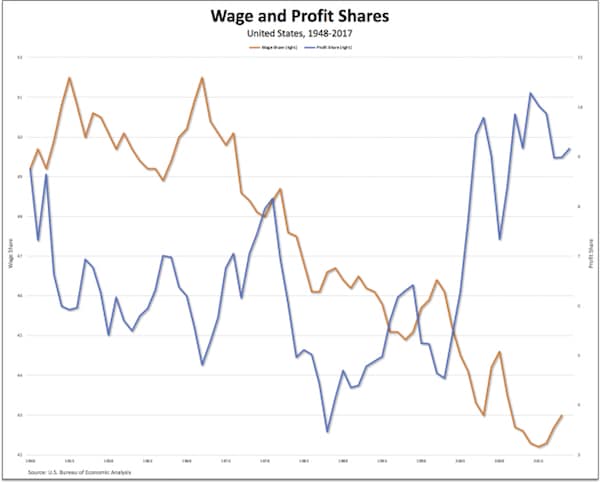

Consider the data Edsall himself cites, which are illustrated in the chart at the top of the post. Since 1970, the wage share of national income (the orange line) has fallen by more than 15 percent. Meanwhile, beginning in 1986, the profit share (the blue line) has risen by 164 percent. For decades now, under both Democratic and Republican administrations, a class struggle has been waged by corporate boards of directors and workers—and the working-class has been losing.

It’s true, they’re still losing under Trump. But they also lost during the recovery from the crash of 2007-08. Just as they did in the decades leading up to the greatest crash since the first Great Depression.

In fact, one can argue that capitalists’ remarkable success in extracting more or more profit from workers is precisely what created the obscene levels of inequality in the distribution of income and wealth that have left the majority of the U.S. population falling further and further behind—and, as a consequence, the election of Donald Trump.

The problem is not, as liberals would like to believe, that exceptional circumstances—market imperfections—have turned the tide against workers. It’s that class struggle is inherent to capitalism, and workers are only useful as creators of the enormous profits captured by their employers.

As I see it, class struggle between employers and workers can’t be solved by reforming the labor market. It can only be eliminated by getting rid of the labor market itself—that is, by moving beyond capitalism.

That’s a real solution to the problem of class struggle that neither Trump nor American liberals are interested in thinking about.