Project Cybersyn was an ambitious political and economic project introduced by Salvador Allende’s socialist government in Chile in the early 1970s. It was an experiment of socialist design that attempted to harness pioneering cybernetic models of complex systems to run a national economy. Cybersyn was explicitly positioned by its creators as an alternative to the top-down economic planning of the Soviet Union on the one hand and the market anarchy of capitalism on the other.

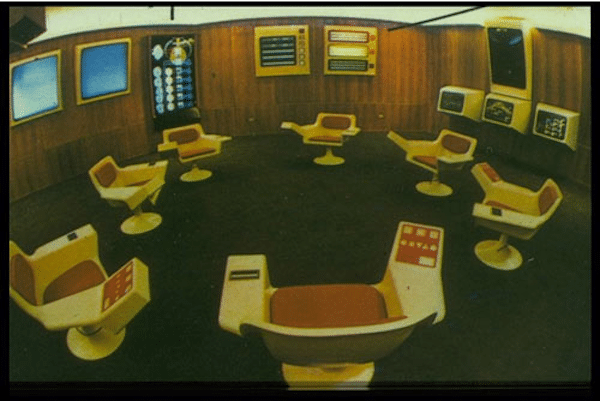

The plan was simple but revolutionary: following the vast nationalisation process already underway in Chile, every factory in the country would regularly send production data through a communications network (called Cybernet) to an ‘operations room’. A collection of democratically-elected officials could then make up-to-date calculations, simulations and decisions on the country’s economic output and feed these back, in real-time, to the factories for necessary adjustments. How much food are we producing and how much do we need? Are we producing enough of X so that the average person can have access to it? And so on. The mastermind behind the project, Stafford Beer, ultimately wanted the project to be more and more participatory, although the 1973 military coup put a stop to this possibility.

Perhaps the most interesting use of the Cybersyn technology was in 1972, when truck drivers, backed by the U.S., walked out in an attempt to destabilise Allende’s administration. The action almost brought the country to a standstill. Without trucks to supply food and raw materials, and with many roads blocked, it could have been the end of the socialist government. However, the many workers sympathetic to Allende took matters into their own hands, using Cybernet to relay key information from the shop floor. Together, the government and workers coordinated a substitute truck service that could supply the country with the resources it needed. Factories banded together, trading supplies and materials to maintain production, and community organisations such as mothers’ centres and student groups began to run supply networks.

It worked. Chile’s logistical infrastructure was back on the road–temporarily powered by the workers themselves. For a moment, organised workers had effectively co-run Chile’s economy, with what was essentially a primitive series of WhatsApp groups.

Ultimately, Allende’s days were numbered, and a military coup (again backed by the U.S.) made sure that the potential of Project Cybersyn would be buried along with the socialist dreams behind it. Chile became a neoliberal laboratory, ruled by a vicious dictatorship.

A new generation

As the neoliberal era crumbles under its own contradictions and political impasses, perhaps it’s time to revive the spirit of Cybersyn for a new generation of progressives.

Today, we have technical capacities far beyond what was available to the Chilean government of 1972–but these technologies are not currently coordinated to create a fairer and more democratic society. Project Cybersyn shows that technology is mere potential that requires political guidance and form to achieve progressive goals.

Cybersyn didn’t manage to achieve its aims of democratic worker control, but we can learn from its unique example to envision our own technologically-advanced democratic future.