You are either alive and proud or you are dead, and when you are dead, you can’t care anyway. – Steve Biko, Interview with American journalist a few months before his death.

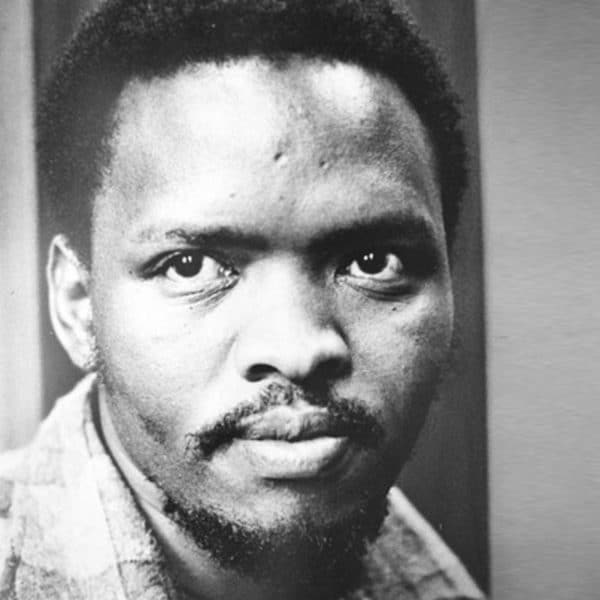

Mention the name of Steve Biko today and, although a few people might recall the 1980 Peter Gabriel song or the 1990 film Cry Freedom, many will not know who you are talking about. But this neglect is undeserved, for despite belonging to a specific historical moment–the struggle against apartheid in late 1960s and early 1970s South Africa–Biko`s packed and purposeful life, cut short at the age of 30 in 1977 by the South African Security forces, together with his radical political ideas, offer us examples of resistance that still have the power to inspire and instruct.

One significant aspect of Steve Biko’s continuing significance is his rejection of liberalism as an effective means of achieving major social change. Convinced that “no group, however benevolent, can ever hand power to the vanquished on a plate…” he knew that hard struggle (but not violent struggle, as his enemies claimed) was always required.

He argued that Apartheid couldn’t be ended by gradually closing of the gap between black and white communities. Oppositional groups and movements must rather become sufficiently strong and independent, so that they are able to engage with those in power as equals. Whilst political strength for us may look rather different than it did then, Biko’s rationale for deciding to form a separate black student group (SASO) in 1968 and face down the charge of ‘reverse racism’ remains ever-topical, where oppressed groups are often accused of the same spurious charge for organising to build power. Building different kinds of oppositional capacity is crucial to political success because substantial change will only come about when the powerful have their backs against the wall.

As well as rejecting liberalism, Biko rejected simplified versions of Marxism. He believed firmly that (a class-based understanding of) race, rather than ‘simply’ class alone, was at the root of inequality in South Africa and that false consciousness didn’t have to be a permanent state. Indeed, he shared the optimistic and committed outlook of the 1960s’ Black Theology movement, which saw Jesus as a God fighting on behalf of the downtrodden.

Biko recognised that it was essential to challenge Black people’s internalised sense of inferiority and fear, so that they could move to a new identity. For this to happen, he argued, they needed to undergo a process of ‘conscientization’–a concept borrowed from the Brazilian literacy educator, Paulo Freire, which pointed to how developing individuals’ powers of critical reflection and action can produce fundamental change.

For conscientization to work properly, Biko believed it was essential for leaders to remain close to those they were assisting, taking serious account of their views. Otherwise there was a serious risk of reproducing in a different form the authoritarianism and injustices of mainstream society. Oppositional organisations or projects, small and large, need to ensure then that they pre-figure, in their structures and processes, the democratic society to which they are committed.

Worth noting also is the fact that from his early days of political activism, Biko was imaginative about the tactics he used. Hence, at the 1967 meeting of the country`s national student organisation (NUSAS), in which black delegates were required to live and eat separately from their white counterparts, he used his homeland language to address the congress at one point rather than English, in order to ridicule its failure to resist the Government`s segregation policies.

A year later he was supporting the idea of walking briefly across and back a local boundary line, to subvert the law that stipulated that black people should not reside in certain areas for more than 72 hours. Such actions might seem to be unnecessarily restrained, given the brutality of the South African State, but they chime with the activism of other 60s` movements, such as the Yippies in the US, designed as it was to raise people`s awareness of the absurdity of authority.

The BCM also encouraged the growth of cultural activity, whether home-grown or international, to allow marginalised voices to be heard and identities to be strengthened. Little wonder that soul-music’s defiant message–“say it loud! I’m black and I`m proud”–became so popular with Black people across the country.

Always extremely articulate, Biko was ready to make use of any platform, including those associated with the enemy, to gain publicity for his cause. Thus, as a defence witness at the 1975-6 trial of his Black Power Convention colleagues on terrorist charges, he chooses his words carefully, not wanting to incriminate his colleagues but also unable to resist the opportunity to wittily turn the table on his opponents:

Attwell: It is not in the BPC constitution, is it, a rejection of violence?

Biko: No, it is not there. Nor is it anywhere in the constitution of the Nationalist Party.At other times during the trial, he corrects the Judge and explains his political position with such coherence and force that the authorities must have regretted he was ever given the chance to speak.

A further aspect of Biko`s approach to politics was his rejection of sectionalism, for he was always willing to form alliances with other individuals or groups–as indicated by his arrest in 1977 for defying a banning order in pursuit of one such alliance.

Biko believed in the impact that words could make–his superbly written Frank Talk columns in SASO`s newsletter are evidence of that. However, although speeches and articles were necessary, activists, he also thought, had to become involved in various kind of community projects. Following the example of Paulo Freire, he encouraged student volunteers to set up literacy classes and to run health-centres and co-operative factories–all of which developed individuals’ ‘self-reliance’ and understanding of the nature of their oppression. The first task of the Zanempilo medical centre was to dispense health-care but the facility also demonstrated to the black population that they too, as doctors and nurses, could provide as well as receive aid. Community work has a long and honourable tradition in radical politics and the South African experience reminds us of its potential to strengthen political consciousness and to prepare the ground for future struggles.

If the work of Biko and the Black Consciousness movement didn’t produce a revolution alone, it did lay the ground for future challenges to South Africa`s apartheid system, including the Soweto uprising in 1976 and other forms of unrest and protest. Just as significant, however, is Biko’s and the Movement’s legacy for today, when the forces of right-wing populism are offering dishonest and inhumane solutions to current problems. It is a legacy that reminds us that the most effective way to fight injustice is to help people see through the myths and lies that are used to keep them in their place, so that they can understand the real causes of their oppression and the power they possess to overcome it. As Biko memorably wrote in 1971–“The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”