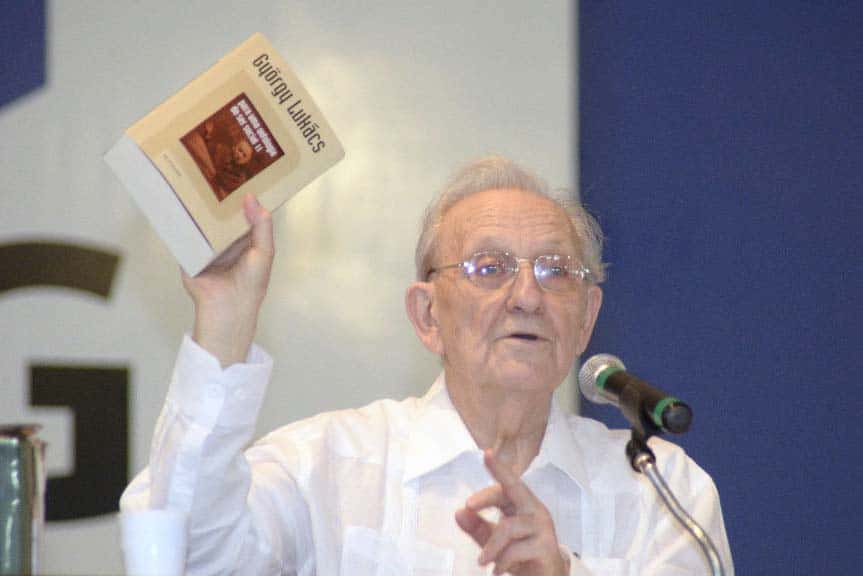

This previously unpublished essay is taken from volume 1 of Mészáros’s Beyond Leviathan: Critique of the State, which remained incomplete at the time of his death in October 2017. —The Editors

1. The Descending Phase of Capitalism and the Historical Anachronism of the State

The state, as we know it, has been constituted across many centuries. In its present-day reality it confronts us with the historically specific determinations of the capital system as a structurally articulated and embedded mode of overall decision making, with its fundamental powers as well as their necessary limitations.

Despite all attempts—and corresponding vested interests—bent on the eternalization of this mode of overall societal decision establishing conditions in which, as they say, “there can be no alternative,” the state is inherently historical not only in the direction of the past: its ground of objective determination and articulation; but also with regard to the future that circumscribes its historical viabilities or their absence in terms of the unfolding necessities and developments.

When addressing the grave issues of the state formations of our time it is vital to keep everything in its proper historic perspective, contrary to the temptation to confine attention simply to the vicissitudes of the capitalist state. As Marx clearly underlined it, capital did not invent the production and exploitation of surplus labor.1 Likewise, capital did not invent the state, nor did it invent the inescapable need for finding some modality of overall decision making in all forms of society in tune with the prevailing requirements of the social metabolism.

In terms of the two vital conditions just mentioned, the need to find and secure a sustainable mode of overall decision making is much more fundamental than the form in which that mode can be articulated even on the broadest scale through the state. The need to have a sustainable mode of overall decision making is an insurmountable requirement for humanity, compared to the historically limited form in which such mode can be institutionalized and enforced through the state. Inevitably, therefore, reversing the order of priorities deeply affects our understanding of the nature of the whole complex of related issues. Worse still, to confine our approach to the historically specific present-day dimension of the state would be hopelessly distorting. What must be strongly underlined in the present context is that our primary concern is the nature and manifold transformations of the state in general in its epochal determinations. For the state in some of its forms of existence originated thousands of years before capitalism. This fact has weighty implications for grasping the inherent characteristics and the necessary limitations of the state. In this respect it must be recalled that capitalism, to use Marx’s expression, “dates historically speaking only from yesterday.”2 Accordingly, in our critical assessment of the acute problems of the contemporary state we must evaluate not only the now clearly identifiable political contradictions but also a set of deep-seated and multi-dimensional historical relationships. This is because the complex relationships in question are characterized by a materially grounded dialectical interaction in which changes and actually feasible prospects of development cannot be made intelligible at all without fully taking into account also the underlying continuities.

In this sense, bearing in mind also the significant continuities, the fundamental structural determinations of the state as such are of seminal importance. It is in virtue of the fundamental structural determinations of the overall complex of dialectical reciprocities and dynamic interchanges among the various factors of social continuity and discontinuity, inseparable from the always historically shaped material ground, that the state can fulfill its overall decision making role also transhistorically, within well definable limits. This is so no matter how weighty might be the inexorably arising historical specificities that must be brought into play under the changing circumstances.

Thus, to take a crucial example, under the conditions of the capitalist mode of societal reproduction the directly economic compulsion of the producers in effectively determining the continuing class-oppressive relationship between capital and labor plays a paramount importance, as a qualitatively novel historically specific social characteristic in overall decision making compared to the slave-owning and feudal past. Indeed, paradoxically, in the political domain this economically dominant novelty helps to create the false appearance of an—ideologically rationalized and idealized—“democratic system.”

Yet the truth of the matter highlighted by the revealingly persistent epochal continuities inseparable from all forms of antagonistic political formations is that the capitalist state, despite all “democratic” self-mythology, could never in its history abandon the authoritarian and unceremoniously enforced exploitative hierarchical assertion of its rule. It always forcefully protected—and had to protect—with all might at its disposal the decision making power of the ruling class. In our time such power is vested in the “personifications of capital” (in Marx’s words) on account of their politically—and even militarily— secured proprietorship of the means of production that controls the reproduction of the social metabolism in its entirety. By no means surprisingly, of course, all this must be represented as being fully in consonance with “constitutionality” and unobjectionable “sovereignty,” in the best interest of all.

However, the circumstance that the state as such can fulfill its role and assert its power across a variety of ages all the way to the present even in terms of its most problematical, necessarily authoritarian, determinations does not mean that it is bound to be able to do that indefinitely, as the apologists of the established order proclaim. Far from it. The state as such—and of course all of the particular state formations—are inherently historical within their structurally articulated overall limits, and fatefully counter-historical (that is, manifesting the most contradictory form of historicity) beyond such limits.

To be sure, the state is historical in its materially grounded objective constitution and structural determination. Like all human institutions, the state is itself historically produced and maintained across the ages. But by the same token, the state is also inevitably subject to the conditions required for making itself historically viable and sustainable—or not when it tends to move toward failure—as the overall decision making power under the necessarily changing conditions of historically shaped nature (including ecologically in a truly literal sense vital nature) and the ongoing determinations of the societal reproduction process.

That means, in other words, that the state as the historically constituted “Sovereign” is not simply in a position of forcefully imposing on societal reproduction some historical necessities in tune with the prevailing material and structural determinations of their time. The state can certainly do that, as one side of the equation, according to the objectively identifiable conditions and institutional forces that happen to prevail under the given historical circumstances.

At the same time, however, and inescapably, the state is also necessarily subject in a contrary sense to the newly unfolding historical necessities when it becomes out of tune with the emerging, materially constituted, needs and conditions not only in its limited historical specificity—as some form of particular3 state formation—but altogether in its epochally defined innermost characteristics and objective structural determinations whereby it is customarily capable of asserting its power across the ages; namely in its overarching capacity as the state as such. It is in that sense that the state as constituted in history becomes in our time an overpowering historic anachronism, under the circumstances of its epochally descending phase of development. This elemental change represents not a passing trend but an irreversibly descending phase of development, when the state’s normally as a matter of course enforced mode of operation not only loses its historical legitimacy but becomes counter-historical on account of the state as such—and not simply as this or that particular state formation—necessarily failing to fulfill its customary overall decision making and corrective functions in a historically viable form.

The epochally changing and in the longer run necessarily prevailing conditions characteristic of this descending phase are not simply historical contingencies that could be more or less easily overcome through the adoption of some suitable state measures, as—for instance—the shift from traditional liberal democratic state practices4 to some dictatorial form of rule, like Mussolini’s Fascist takeover in Italy experienced in the relatively recent past of European history. They are qualitatively novel historical necessities precisely in view of their epochally defined character, underlining the grave structural crisis of politics in general and the crisis of the traditional mode of overall decision making in terms of ultimately always authoritarian state determinations.

The burdensome historical necessities in question, as manifest in the political domain, are not intelligible at all in and by themselves, contrary to the way in which they are as a rule assessed in the interest of retaining the state-legitimating framework of evaluation and social practice. For in actuality the structural crisis of politics in our time matches in its own way the structural crisis of capital’s social metabolic order as a whole. Consequently, the inherently epochal determinations of this combined structural crisis raise the need for appropriate epochal solutions, to be consciously adopted in due course in tune with the challenging historical necessities.

2. Antagonistic Political Formations

The materially grounded common denominator of all antagonistic political formations, from the most ancient empire-building attempts to the present-day “democratic systems,” is the class-exploitative production and extraction of surplus-labor. All antagonistic political systems are structurally embedded in some kind of social monopoly of property that can effectively control the given mode of material production and societal reproduction. Without that form of material grounding the political systems in question would be totally incapable of sustaining themselves.

Understandably, antagonistic political formations are not constituted for eliminating or superseding class antagonism. Since they are materially based on the class-antagonistic modalities of controlling the societal reproduction process and the corresponding exploitative extraction of surplus-labor, they must preserve it as their own substantive ground. And they can do that by sustaining in their own way the production-securing monopoly of property itself—under the historically at any time feasible form of its viability—in its given structural prevalence. That must be done no matter how antagonistically the class exploitative dominance of the existing order might be contested by the people who perform the necessary productive tasks. The primary role of antagonistic domination must be therefore directed at the social forces that might contest the production-securing monopoly of the historically under the given conditions sustainable means of societal reproduction.

To be sure, politically controlling a social metabolic order which is materially structured in an antagonistic way cannot be itself other than antagonistic by its innermost determination. Of course the particular forms of antagonistic political control can and indeed must vary, from extreme dictatorial to formal democratic varieties, according to the historically changing circumstances. Likewise, as historical records demonstrate, even the particular class configurations of domination and structural subordination vary, in tune with the unfolding historical changes, from the slave-owning and feudal forms to the bourgeois. But the substance of the class-exploitative production and extraction of surplus-labor must remain, together with the class-interested usurpation of the overall power of decision making.

Moreover, the impact of the antagonistically embedded and secured mode of overall decision making by its very nature cannot be confined to the internal dimension of domination, as exercised over the structurally subordinated class of the given particular society. This modality of self-imposing decision making—since, as the claimed “sovereign power,” it is unlimitable in its own objective terms of reference by what should be some intrinsic determination of its character—by the selfsame logic of sovereign unlimitability the established antagonistic overall decision-making power as such must project also outwards its aspirations for domination. And of course, as a matter of principle, absolutely no outside forces are admissible as legitimately limiting the self-asserting power of the established antagonistic political formations without their proudly professed inherent nature being unforgivably violated precisely in its claimed “Sovereignty” and properly punished for it as a result.5

The sophisticated political and legal theories and justifications devised to this self-serving effect are, of course, elaborated at a relatively late stage of historical development. However, the antagonistic and destructive social practice of securing territorial expansion—from limited tribal conquests to the establishment of vast empires—at the cost of some adversary or enemy goes back to time immemorial.

In this sense we are confronted by a twofold antagonism: the internal and the external. The latter is oriented to outward domination which would be inconceivable without securing through the primary internal class-domination the required stability capable of yielding outward conquests. Thus the internal and external dimensions of self-assertion of all antagonistic political formations are inseparable. Accordingly, not only the internal repression of the structurally subordinated class but also war, on ultimately unlimitable scale, must be endemic to this usurpatory mode of antagonistic overall decision making from which the overwhelming majority of society must be substantively excluded.

This is so even if under the formally “legitimated” pretences of non-existent “consensuality” some incalculably destructive wars—like the relatively recent Vietnam war, or even more recently, the Iraq war, with their cynical justifications—are “lawfully” imposed on society, as demonstrated by the subsequent state-apologetic legal contortions. At the same time, given the dominance of the ruling ideology, historical consciousness in general is negatively affected in every country under the impact of state-apologetics. In part this is because war itself can and often does act in a mystifying way on historical memory. For this reason so much remains to be both clarified and rectified in humanity’s historical consciousness even when in epochal terms the antagonistic modality of overall decision making power through the known political formations becomes a historic anachronism, at the irreversibly descending phase of humanity’s class-oppressive systemic development.

3. The Epochal Crisis of the State and the Escalation of Destructiveness

The first time ever in history the absolutely fundamental epochal dimension of these problems—concerning the historically no longer tenable antagonistic structural determination and the corresponding state-enforcement of the societal reproduction process—was in fact conceptualized by Karl Marx. This became possible under the conditions of the renewed revolutionary upheavals all over Europe in the 1840s, following the relative stability after the Napoleonic wars. At that time Marx fully realized that thousands of years of materially embedded and politically buttressed class antagonism cannot be overcome without the radical supersession of the state itself. This is why Marx advocated the withering away of the state to the end of his life, despite all disappointments in the development of the working class movement itself that came to light in a most disheartening way at the time of the debates over the Gotha Program.

Those who deny his unending conviction about the necessary withering away of the state as such from the time of his very early critique of the state are, knowingly or not, in complete disagreement not only with this one aspect of his conception but with the whole of it. For the Marxian view that capital had entered its epochally irreversible descending phase of development applied and continues to apply not only to the increasingly more destructive economy in its direct relationship to nature, of which Marx was fully aware far ahead of anyone else in his time,6 but to the capital system in its entirety. In his view capital’s descending phase of development in its entirety was irreversible in a truly epochal sense, irrespective of how difficult and contradictory the full consummation of the overall historical process, in all of its dimensions, might have to be.

Accordingly, it would make no sense at all to exempt the antagonistic political formations from such consideration. For, inseparably from capital’s directly material reproductive order, also the political dimension had entered the epochally irreversible descending phase of its historical course of operation. In fact one side of the two could never sustain itself on its own, without the supporting power of the other. Moreover, under the emerging circumstances the increasing material antagonisms could not be mastered by the ruling order without the corresponding transformation of the attempted state-imposed corrective measures through the articulation of the globally ever more belligerent modern imperialism, as indeed we could witness that in the last three decades of the nineteenth century. “Iron Chancellor“ Count Otto von Bismarck was one of the most dominant figures of those dramatic decades. And he did not hesitate at all to enlist even some working class support in his country for asserting German imperialist aspirations, with the treacherous secret collaboration by Ferdinand von Lassalle who played an infamous role in splitting the German working class movement.

Thus the withering away of the state as a contradictorily unfolding prospect appeared on the historical horizon not as the need to overthrow the capitalist state, a naively superficial idea held by many directly criticized already by Marx. In response to the fateful destructiveness and its growing intensity by the capital system in its entirety, the historic challenge presented itself as the absolutely vital necessity to radically supersede all conceivable forms of the alienated, antagonistic modality of state-imposed overall political decision making. Capital’s clearly identifiable destructive power in the material domain could not be defeated in its own limited terms of reference, in the materially productive sphere alone. The epochal sustainability of the state’s overall decision making power and the material preponderance of capital’s mode of social metabolic control stood and could only fall together. This is what had set the fundamental emancipatory task—and continues to set it for the future as well—until it is successfully accomplished.

As I stressed in my Isaac Deutscher Memorial Lecture, The Necessity of Social Control,7 the critique of capital’s epochally irreversible destructiveness itself was far-sightedly confronted in Marx’s writing at a very early stage. Already at the time of sarcastically criticizing Feuerbach for his vacuous characterization and idealization of “nature” Marx highlighted the unavoidable ecological damage produced by capitalistic industry in really existent nature. And in the same early work, on The German Ideology, he forcefully underlined that the fundamental structural change of the societal reproductive order that he was advocating concerned the vital historic stake of humanity’s survival. This is how he developed that idea already there in different contexts, with growing intensity:

In the development of the productive forces there comes a stage when productive forces and means of intercourse are brought into being which, under the existing relations, only cause mischief, and are no longer productive but destructive forces.…8 These productive forces receive under the system of private property a one-sided development only and for the majority they become destructive forces.9… Thus things have now come to such a pass that the individuals must appropriate the existing totality of productive forces, not only to achieve self-activity, but, also, merely to safeguard their very existence.10

Capitalism experienced a profound economic crisis throughout the 1850s and the early 1860s. So much so that even the editorial articles of the leading bourgeois theoretical organ, The Economist, were written with alarm and even gloom.11 Nevertheless, while noticing this alarm and even tempted for rejoicing over it for some time, a note of caution was well in order on the socialist side of the fence. Thus Marx wrote in a letter to Engels:

There is no denying that bourgeois society for the second time is experiencing its 16th century, a 16th century which, I hope, will sound its death knell just as the first ushered it into the world. The proper task of bourgeois society is the creation of the world market, at least in outline, and of production based on that market. Since the world is round, the colonisation of California and Australia and the opening up of China and Japan would seem to have completed this process. For us, however, the difficult question is this: on the [European] Continent revolution is imminent and will, moreover, instantly assume a socialist character. Will it not necessarily be crushed in this little corner of the earth, since the movement of bourgeois society is still in the ascendant over a far greater terrain?12

This qualification was, of course, absolutely necessary. However, the crucial issue was and always remains that the potentially emerging, and for determinate historical circumstances actually prevailing political and economic reversals do not eliminate the fundamental historic trend of the capital system’s epochally descending phase, although they significantly modify its conditions of unfolding and ultimate assertion. The unavoidable, materially grounded difficulty in this respect is that in really existing history we do not find only tendencies but inevitably also counter-tendencies. And, of course, they necessarily interact with one another.

What ultimately decides the issue is the inherent nature of the objective historical tendencies and counter-tendencies themselves and the far from arbitrary or wishfully definable character and modality of their inevitable interactions. Since we are talking about the materially grounded reality of such interactions their reciprocity is characterized by objective determinations, inseparable from their structurally relevant historical considerations. In other words, the historical tendencies and counter-tendencies cannot be simply presented in a one-to-one relationship to each other, irrespective of their both structurally and historically determined relative weight, equivalent to their inherent nature. That is what carries with it in their reciprocity a corresponding differential impact on one another. And that is indeed what makes some of them historically more sustainable than the others, or even renders some of them with regard to their required historical viability absolutely unsustainable, no matter how much they might be able to dominate the given order—with their state-repressively imposed counter-historical preponderance—under the prevailing circumstances.

Grasping these difficult historical relationships in accordance with their true theoretical and practical importance is feasible only within the conceptual framework of a materially grounded objective dialectic. For, ignoring such vital material grounding and sweeping aside dialectics altogether can yield in theoretical terms only empty tautologies, and in the domain of strategically relevant social practice nothing but hopeless disorientation. Thus it was by no means accidental that the fateful disarming of the German Social Democratic movement that culminated in its disastrous capitulation to imperialism at the outbreak of the First World War, was theoretically prepared by the neo-Kantian assault on dialectical thought, carried out by Lange, Dühring13 and others in the last decades of the nineteenth century, in full affinity with the subsequent promotion of Bernsteinian revisionism.

This operation was conducted with great cynicism and hypocrisy. The proponents of the neo-Kantian wisdom were on the face of it thundering against Hegel, but their real target was Marx’s revolutionary dialectic that demonstrated the untenable contradictions of the established order and was generating a major impact on the working class movement. That is what had to be rejected by the supporters of the established order also when it had to be done in its pretendedly pro-workers disguise. That line was followed because the Marxian dialectical exposure of the systemic contradictions of capital was concerned with a materially vital critique of the established societal reproductive order and its state formation. This is why dialectic had to be ruled out altogether by Marx’s adversaries, in order to give some semblance of credibility to their own position.

To quote a letter by Marx:

What Lange says about the Hegelian method and my application of it is really childish. First of all, he understands nothing about Hegel’s method and secondly, as a consequence, far less even about my critical application of it.… Herr Lange wonders that Engels, I, etc., take the dead dog Hegel seriously when Büchner, Lange, Dr Dühring, Fechner, etc., are agreed that they—poor dear—have buried him long ago.14

In this sense, it was the materialist, radically critical application of the dialectic to the antagonisms of the existing societal order that had to be eliminated by the neo-Kantian apologetics of society. Bernstein, too, glorified the same approach. He dismissed the fundamental tenets of Marx’s theory (including in a prominent place the idea of any social or political revolution) with the pretext that such ideas were only “planks” of a “dialectical scaffolding”15 and in “modern society” they could not have any meaning. In his book of appallingly low theoretical standard, in the same spirit of insulting insolence with which he dismissed Marx’s revolutionary theory as nothing more than “dialectical scaffolding,” Bernstein rejected Marx also as a “dualist thinker”16 and a “slave to a doctrine”17 while hypocritically playing lip-service to his “great scientific spirit”18 without indicating in any way what that “scientific spirit” by a “plank-peddler slave of a doctrine” might really amount to in the idealized “modern society.” Moreover, with arrogant paternalistic attitude toward the workers, Bernstein also pretended to assume the moral high ground—by saying: “Just because I expect much of the working classes, I censure much more everything that tends to corrupt their moral judgement.”19—and doing that in the midst of his own cynically pursued moral betrayal of the cause of socialism.

These were most revealing responses to the social and political crisis inseparable from the epochally descending phase of the capital system’s development. For the historical antagonist and hegemonic alternative to capital, labor, had to be prevented by its own claimed “political arm” from taking a radical stand against the system. That was the primary function of “evolutionary socialism” propagandized without any ground of reality by Bernstein and his followers. In the end their approach succeeded not in bringing the falsely postulated “evolutionary socialism” by the slightest degree nearer to its realization but, on the contrary, in destroying German Social Democracy altogether.

The both theoretically and practically important point to stress is that the nefarious Bernsteininan etc. accommodatory response itself and the object of its disarming action—namely the forces that were beginning to engage in the period which we are talking about in confronting the historic anachronism of capital’s rule and its repressive state—cannot be properly understood as standing in a one-to-one relationship. In truth there is a very good reason why all talk simply about “reciprocity”—and of course as a rule conceived in a wishful sense as “mutually balancing reciprocity”—in relation to historical tendencies and counter-tendencies must produce empty tautologies in theory, combined with more or less veiled social apologetics. That reason is because the adoption of such approach willfully ignores in the relationship concerned—despite its objectively given determinations—the moment or factor of “overriding importance,” called by Marx the “übergreifendes Moment.”

In the real world the response adopted against its adversary cannot arbitrarily reshape the inherent nature of the historical tendency to which it must respond. The response is a response and not some wholly self-constituting and materially as well as politically self-grounding entity or complex. As a time-bound counter-tendency arising under determinate historical circumstances it must confront the problems or dangers represented by what it is called upon to counter with its own resources and modes of feasible action. But the counter-tendency is in the first place necessarily dependent on the objective determinations of the tendency to which it must respond. It cannot wipe out at will the actually given historical necessities and establish its own unchallengeable necessity on some absolute ground.

To be sure, some counter-moves can be always devised by the ruling order even in a situation of extremely grave revolutionary crisis by which it is threatened. The ruling order has on its side both the immense material resources of societal reproduction—usable in many different ways against its opponents—and the violent repressive power of the state. But all that is very far from conclusive. For in the case of the capital system’s epochally descending phase of development the real issue is and necessarily remains: whether or not the counter-measures of the response adopted under the given conditions are sustainable not just for the moment but for a historically viable future.

As we know from historical chronicle, the response of late nineteenth century capitalism to its intensifying crisis was the establishment of monopolistic imperialism. That is to say, the institution of a form of imperialism that had to be very different from its historical antecedents in the past in a crucial sense. For the new imperialism had to reconstitute itself on increasingly monopolistic material productive foundations. At the same time—piling up explosive dangers on the military plane on a totally unforeseeable scale—the monopolistic imperialist capital system was utterly incapable of overcoming its customary military collisions among the handful of dominant state powers that inevitably had to contest one another, as inherent in the nature of the established national state formations.

The question that remains to be answered: is this response to capital’s epochally descending phase of development—both in the material field and in the state-legitimated political domain—historically viable? As we had to learn from bitter historical experience, the fundamental objective determinations of monopolistic imperialism in the material domain, coupled with the systemic failure to overcome the necessary antagonisms of the national state formations on the political plane, carried with it in due course the necessary eruption of two world wars, with their devastating consequences, including the extermination of hundreds of millions of people. That is the undeniable historical record.

Thus the response of the capital system to its epochally descending phase of historical development—characterized by ever-increasing destructiveness—was fatefully self-contradictory. For the untenable systemic destructiveness that perilously signalled the arrival of the epochally descending phase of development itself and brought to the historic stage the necessary hegemonic alternative to capital’s rule was “countered” by capital through a formerly even unimaginable escalation of destructiveness both in the domain of material reproduction, with its uncontrollable impact on nature, and on the state-repressive and military plane, foreshadowing the very real danger of humanity’s total self-destruction in the event of another global war. Obviously, nothing could be historically less viable than that.

4. A Global Coercive State?

Yet, the advocacy to solve these problems through some modality of state repression cannot be abandoned. Not even when the objective conditions of societal interchange on an unavoidable global scale would, on the contrary, require a radical critical re-examination of the feasibility of its success. For in our time, inescapably, the requirement of long-term historical viability includes in its concept the necessity of global sustainability.

In the more remote past this constraint did not assert itself, of course. Imperial conquests and state repressive actions could be pursued without any consideration of their global implications. And even at the outset of the epochally descending phase of the capital system’s development, vast areas of planet earth, with immense populations, were still left behind in a materially productive sense. They offered for some time ample scope to monopolistic imperialism for asserting its counter-tendency and prolonging the capital system’s life-span.

To be sure, on the military plane the prohibitive dimension of humanity’s antagonistic interchanges appeared with the nuclear weapons soon after the Second World War. But even then material destructiveness in the industrially productive domain, affecting also nature on a potentially irreversible scale,20 was still far less than what it has become as a result of the eruption of the capital system’s structural crisis through the activation of its absolute limits. Thus in our time the refusal to abandon the prospect of military destruction on a potentially global scale, as the ultimate arbiter over the necessarily persistent and even intensifying global antagonisms, have become absolutely prohibitive. Accordingly, no solution to humanity’s antagonistic contradictions can be considered rational unless the necessary requirement of its historical viability is simultaneously combined with its global sustainability.

However, notwithstanding the absolutely prohibitive character of ongoing destruction, the promoters of vested interests defy even the elementary demand for rationality. Instead of attending to the causes of global antagonisms, in order to overcome them in substantive terms at their social metabolic ground, they advocate the escalation of state-repression as the enforced “remedy” of their consequences, in the spirit of the fairy tale of “putting back the Genee into the bottle,” and doing that even in global terms. Thus the pernicious notion of “Liberal imperialism”—on the pretext of acting against so-called “failed states”—was championed most irresponsibly in this sense quite recently. In the same sense a prominent writer in the field of bourgeois political economy, Martin Wolf, arbitrarily used the self-justificatory notion of “the global community”—in the name of which the most brutal violations of elementary human rights are in fact committed by U.S. imperialism and its “willing allies”—insisting that “the global community also needs the capacity and will to intervene where states have failed altogether.”21

In this way violent state intervention and repression is advocated, despite its potentially catastrophic consequences. And no one can say how far its aggressive endorsement can go. For even the nightmare conception of a “global coercive state” is advocated in the name of—wait for it— “rationality” as such. Thus we read in the Introduction to the Oxford University Press edition of Leviathan by Hobbes that

it would be rational to form a World State, or, one might add, at the very least a United Nations with sovereign coercive powers.22

The complete absurdity of such “rationality,” adopted by Gaskin from Howard Warrender’s article on Hobbes published in Encyclopedia Americana. Naturally, at the original roots of such pernicious “rationality” we find the belligerent wishful thinking that global state-repression, exercised by the United States, would be permanently capable of fulfilling the role of “sovereign coercive power.” Of course no one should doubt that there are many believers in that disastrous notion in very powerful state-decision-making circles today, especially in the U.S. Toward the end of the last Millennium the aggressive propagandists of boundless U.S. power were saying that the 20th Century was the “American Century,” and from now on the entire new Millennium will be the “American Millennium.” One is reminded of Sir Winston Churchill’s projections that the British Empire—over which he was presiding at the time—will be maintained in its glory “over the next thousand years.”

But there are some sobering questions that must be faced in terms of the projected “Global Coercive State.”

- How could be provided the mind-boggling amount of material resources required, on a globally extended scale, as well as on a continuing basis, for such “Global Coercive State,” at a time when we are experiencing the unacknowledged state-bankruptcy of the most powerful capitalist states; in the case of the U.S. that bankruptcy approaching the astronomic figure of twenty trillion Dollars;

- Would not have to be absolutely prohibitive the cost of its destructively coercive action of which relatively small samples have become evident—in their already prohibitive magnitude—in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq? Well before the humiliating defeat in the Vietnam War General Eisenhower voiced his critique of the catastrophically wasteful and inexorably rising military expenditure. He did that at a time when the “economic black hole” in the United States was still very far from the now undeniable astronomic figure;

- Above all, when will the aggressive state-repression theorists begin to admit that the primary meaning of Sovereignty—based on the objective ground of its necessary determination—is the necessary internal dominance over the structurally subordinate members of the given nation state. Any projection of Sovereignty outward, for the purpose of subduing the encountered inter-state antagonism represented by some other state, must have that internal domination secured as the precondition of its potentially successful action. Moreover, it must have such internal domination not simply in accordance with the “Political Theory of Possessive Individualism.”23 All so-called “possessive individualism” in the domain of Sovereignty must be constituted as class-repressive dominance over those structurally deprived of production-controlling property. Without that it cannot have any meaning at all.

Thus the presumption that the politically devised “Global Coercive State”—situated in the United Nations, or wherever else—could exercise its projected coercive functions without attending to, and eliminating, the internal antagonisms that are bound to be generated at the material reproductive level of the particular countries, is totally devoid of meaning. For the elementary requirement in this respect is the radical overcoming of class-repressive internal antagonism substantively embedded and hierarchically entrenched in the established social metabolic order.

5. The Structural Barriers to Equality

For a very long time in history it seemed to be workable to dismiss opposition to social antagonism, provided that the authoritarian imposition of order could prevail. In France, for instance, the commoners of the Third Estate,24 made up at the early stage of capitalistic developments predominantly by the bourgeois forces—who were for some time welcome alongside the other two Estates in the National Consultative Assembly,25 the Clergy and the Nobility—could be readily ignored in this way by authoritarian Royal power by not summoning that Assembly after 1614, until the explosion of the French Revolution itself in 1789. Ironically, however, by the time of the Revolution large masses of workers have greatly swollen the ranks of the Third Estate, creating thereby immense problems for the future. In fact those great masses played a seminal role at the initial phase of the French Revolution.

Some of the great intellectual figures of 18th Century Enlightenment tried to offer a solution to the growing social and political problems without the advocacy of major societal change, thanks to their view about the advancement of reason as wedded to what they considered on the ground of capital’s material productive power a natural system of equality and justice. Thus Adam Smith, for instance, forcefully argued this enlightenment vision:

As every individual endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value, every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; … By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.26

Thanks to this firmly held belief about the harmony between individual self-serving interest and nature itself in terms of the public good in general, Adam Smith did not hesitate for a moment to exclude not only individual politicians but even the given political institutions from the all-round beneficial management of the productive system which in his view should not be interfered with. This is how he stressed that issue:

The statesman, who should attempt to direct private people in what manner they ought to employ their capitals, would not only load himself with a most unnecessary attention, but assume an authority which could safely be trusted, not only to no single person, but to no council or senate whatever, and which would nowhere be so dangerous as in the hands of a man who had the folly and presumption enough to fancy himself fit to exercise it.27

However, with the eruption of the American and the French Revolutions it became very clear that it was not enough to marginalize the old political order. Something very different had to be put in its place also in the political domain in view of the intensification of the class antagonisms. For in the French Revolution itself the great masses of workers—constituting the large majority of society—were beginning to assert their own class interests in their unavoidable conflicts with the bourgeoisie.

In this sense, with the unfolding of the French Revolution, the traditional way of addressing these problems at times of major crises in history—that is, by replacing one type of ruling personnel by another, e.g. the slave-owning type by its feudal variant, without radically changing the structurally entrenched modality of class-oppression itself—had become extremely problematical, to say the least. And that fundamental social dimension of the necessity of societal change that could positively involve the great masses of the working people never disappeared again from the social antagonisms. On the contrary, major revolutions in the nineteenth and in the twentieth century continued to reactivate it, ever closer to a truly global scale, despite temporary reversals and defeats.

Already before the French Revolution the most radical of French intellectuals, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, tried to highlight the irrepressible social structural dimension of the antagonism in question. He characterized in a powerful sarcastic way the existing state of affairs between the ruling order and those who suffered by it:

The terms of the social contract between these two estates of man may be summed up in a few words: ‘You have need of me, because I am rich and you are poor. We will therefore come to an agreement. I will permit you to have the honor of serving me, on condition that you bestow on me the little you have left, in return for the pains I shall take to command you.’28

The most important part of Rousseau’s proposed solution was the adoption of the General Will as the way to regulate fundamental decision making in accordance with the advancement of reason that could counter antagonistic destructiveness. That idea of his advocacy remained by far the most seriously discussed and defended part of his vision to our own days despite all misrepresentation. Rousseau made it also absolutely clear that the idea of Liberty could not be sustained on its own, against those who were ignoring the demand for social equality. Indeed, he even categorically asserted that “liberty cannot exist without equality.”29 The great Libertador of South America from Spanish rule, Simón Bolívar, forcefully asserted in his actions the belief in equality in Rousseau’s spirit, despite fierce opposition by vested social interest even on his own side.

As we know, Rousseau was no longer alive at the outbreak of the French Revolution but predicted its coming by warning that “I regard [it] as inevitable. Indeed, all the kings of Europe are working in concert to hasten its coming.”30 However, the grave problem remained also in Rousseau’s theory that the fundamental social antagonism in question was inseparable from production-controlling private property which excluded the overwhelming majority of the people. That was what required a structurally different answer from what could be provided even in Rousseau’s radical theoretical framework.

The fundamental premises of Rousseau’s system were the assumption of private property as the sacred foundation of civil society and the “middle condition”—his way of introducing social equality—as the only valid form of distribution adequate to sacred private property in his view. This is how Rousseau argued his case:

It is certain that the right of property is the most sacred of all the rights of citizenship, and even more important in some respects than liberty itself … property is the true foundation of civil society, and the real guarantee of the undertakings of citizens: for if property were not answerable for personal actions, nothing would be easier than to evade duties and laugh at the laws.31

As regards the “middle condition,” according to Rousseau its necessity was inherent in the requirements of social life itself. This is how he had put that point:

under bad governments equality is only apparent and illusory; it serves only to keep the pauper in his poverty and the rich man in the position he has usurped. In fact, laws are always of use to those who possess and harmful to those who have nothing: from which it follows that the social state is advantageous to men only when all have something and none too much.32

What was missing from Rousseau’s noble vision was a tenable insight into the uncontrollable self-expansionary dynamism of capital (which happened to be much better understood by Adam Smith and other bourgeois political economists) and the necessary material power relations that had to go with capital’s preponderant self-expansion. Consequently all talk about the naively equitable “middle condition” could only be swept aside sooner or later by actual historical development as utopian wishful thinking. For it was never enough—nor could it ever be even remotely enough in the future—to advocate, no matter with how genuinely held intentions, a more equitable distribution of wealth without clearly defining the modality of its production. In such matters always the question of production plays the role of the earlier discussed “moment or factor of overriding importance” (the Marxian übergreifendes Moment). That is because critically unquestioned production easily prejudges admissible distribution in favor of its own perpetuation.

6. Formal Versus Substantive Equality

By the time the great German Enlightenment philosopher, Immanuel Kant struggled with these problems, well after the outbreak of the French Revolution, social explosion and military violence engulfed not only France but a significant part of Europe, with a fearful tendency to engulf all of it. Thus the German philosopher offered his alternative to the ongoing blood-letting in these terms:

The narrower or wider community of all nations on earth has in fact progressed so far that a violation of law and right in one place is felt in all others. Hence the idea of a cosmopolitan or world law is not a fantastic and utopian way of looking at law, but a necessary completion of the unwritten code of constitutional and international law to make it a public law of mankind. Only under this condition can we flatter ourselves that we are continually approaching eternal peace. No one less than the great artist of nature (natura daedala rerum) offers such a guarantee. Nature’s mechanical course evidently reveals a teleology: to produce harmony from the disharmony of men even against their will. … The relation and integration of these factors into the end (the moral one) which reason directly prescribes is very sublime in theory, but is axiomatic and well founded in practice, e.g. in regard to the concept of a duty toward eternal peace which that mechanism promotes.33

In this way Kant was keen to underline that his own solution to the apparently intractable contradictions was nothing like wishful thinking or the approval of an unrealizable world of utopia on his part. He insisted that what we were witnessing in his view in a paradoxically violent form was in fact nature’s teleology (a kind of Providence) for the moral end prescribed by reason itself against—but in a strange way precisely through—the selfish ends pursued by the individuals against each other. Thus he extended reason—in that way qualified—to the moral domain and he did that with reference not only to the idea of nature’s sublime teleology but also to the projected mechanism of nature to promote the duty of eternal peace. To a very limited extent in Rousseau’s spirit, Kant even tried to embrace the idea of the General Will, provided that what he called its “practically ineffectual” character could be remedied. This is how he tried to achieve that transformation with his own completion of reason’s demand:

Nature comes to the aid of this revered, but practically ineffectual general will which is founded in reason. It does this by the selfish propensities themselves, so that it is only necessary to organize the state well (which is indeed within the ability of man), and to direct these forces against each other in such wise that one balances the other in its devastating effect, or even suspends it. Consequently the result for reason is as if both selfish forces were non-existent. Thus man, though not a morally good man, is compelled to be a good citizen.34

Naturally, actual historical developments refused to adapt themselves to Kant’s noble but totally utopian scheme of things, despite the alleged “natural mechanism” that was supposed to turn the forces directed against each other into an outcome effectually balancing them for the purpose of universally prevailing good citizenship in harmony with the moral end. War and military destruction continued for decades even in the post-revolutionary French and European context, between 1795 when Kant wrote his article on Eternal Peace and the end of the Napoleonic wars 20 years later, and it never looked like ending its ever more perilous hold over human affairs to our own days. For some years after the First World War, people continued to talk about it in a genuine, but very naïve critical sense, as “the war to end all wars.” But as a matter of brutally sobering reality, two decades later the antagonistically divided forces of humanity were fighting each other in another global war. And in our time, in place of securing “Eternal Peace,” only the certainty of humanity’s total self-destruction has been added—with the weapons of nuclear, chemical and biological mass destruction—to the explosive dangers of our antagonistic social metabolic order, under the ultimate command structure of our historically anachronistic state, in the event of yet another global war.

In Kant’s own scheme of things everything remained within the political domain, notwithstanding the German philosopher’s moral exhortations and his postulated teleological mechanism of nature. What made all such schemes utterly hopeless was that the material structural determinations of the established social reproductive order could not be subjected to any substantive critique in the interest of a sustainable qualitative change.

That was the reason why the projected “cosmopolitan or world law”—re-animated in the twentieth century even in some institutional variety, like the League of Nations—remained precisely “a fantastic and utopian way of looking at law,” despite its eloquent denial by Kant himself. For in reality even the most solemnly decreed laws can be—and as a rule are indeed—twisted and turned with the greatest ease, in the service of diametrically opposed interests, whenever the underlying material determinations so require.

The insuperable contradiction in this respect was—and still remains—the wishfully envisaged removal of the material dimension of the social antagonisms and their attempted transformation into merely formal determinations and differences, under the presumed authority of the stipulated law.

Already Kant spelled out very clearly this line of approach, with a perversely presumed analogy with some kind of “natural” order of appalling inequality. These were the words of his attempted justification of the unjustifiable:

the welfare of one man may depend to a very great extent on the will of another man, just as the poor are dependent on the rich and the one who is dependent must obey the other as a child obeys his parents or the wife her husband or again, just as one man has command over another, as one man serves and another pays, etc. Nevertheless, all subjects are equal to each other before the law which, as a pronouncement of the general will, can only be one. This law concerns the form and not the matter of the object regarding which I may possess a right.”35

To be sure, no one in their right mind would ask today women to obey their husbands the way in which Kant presumed it to be right; nor indeed to order the members of the structurally subordinate class to “obey the rich who pay them” in the spirit of the Kantian upside-down vision of the material reproductive order. But can we talk today about the substantive reality of the legally proclaimed equality of men and women in our society? Or could we consider even for a moment right and proper the monstrous substantive inequalities in our society in all domains just because the law puts its blessing on them?

Tragically, however, Kant was proved to be right in that the system of law enforced by the state prevailed—and continues to prevail—in the sense that the “equality of the citizens as subjects” acknowledges only the “form and not the matter” of the vital issues over which a radically different solution is absolutely imperative. This is why the “citizens’ equality” still boils down to the “equal right” to put periodically a piece of paper into the ballot box whereby they abdicate their power of decision making to the ruling order.

Thus Kant succeeded in “remedying” the “practically ineffectual character of Rousseau’s General Will” by emptying it of its material content and turning it into a merely formal device of the pretendedly equitable law. In that way we were also supposed to forget that according to Rousseau himself “laws are always of use to those who possess and harmful to those who have nothing,” as we have seen above.36 Thus Kant had no difficulty whatsoever in decreeing that “The general equality of men as subjects in a state coexists quite readily with the greatest inequality in the degrees of the possessions men have.”37

7. The Substantive Power of Decision-Making

But here we have arrived at an absolutely fundamental question for our own time. Phrasing that seminally important question in terms of iniquitously distributed material possessions, as it is customarily done in a self-justifying way even among some of the greatest thinkers of the Enlightenment, as we have just seen it done by Immanuel Kant, is like “putting the cart before the horse,” so that it cannot—and rightfully should not—move forward at all. For the way in which material possessions are shared among the individuals, as well as by the social classes, is necessarily dependent on a much more fundamental concept of possession. And that overarching possession asserts itself also as the power capable of allocating the great variety of material possessions among the people.

It is that really fundamental concept of possession that has the primacy over these issues, directly cutting also into the heart of the matter of meaningful equality, in contrast to the reduction of both substantive possession and substantive equality by the social individuals into tendentiously class-exploitative formal determinations. To name that absolutely fundamental concept: it is none other than the possession of the power of decision making by the social individuals in a substantive and not merely formal sense over all matters of their life.

In the course of history, as we have known it prevailing in its antagonistic modality of social metabolic reproduction, that fundamental substantive power of decision making had been alienated from the social body and exercised by the ultimate command structure of the state in a necessarily usurpatory way. As the unavoidably hierarchical superimposed overall command structure—in perpetuation of the established antagonistic social metabolic order—the state could not and cannot function in any other way, no matter how destructive might be the consequences even in the form of global wars. And the tragic truth remains that the substantive possession of the power of decision making has never been returned to the social individuals; not even when the proclaimed “new type of the state” promised to found its radically different social legitimacy on that basis.

Significantly, Kant spoke of “degrees of the possessions men have,” claiming at the same time the full compatibility of their “greatest inequality” with Rousseau’s General Will emptied of its material content. However, the qualification of degrees is applicable only to the kind of iniquitous material possessions defended by Kant and others. The real problem that happens to be quite insurmountable by the Kantian—or indeed by any other—formal-reductionist device, including the most promoted fiction of the “equitable democratic state” and its ballot box, is that there can be no degrees of the most vital possession in question. For that absolutely fundamental type of possession is equivalent to the substantive power of decision making by the social individuals over all matters of their life. That is what had been alienated from the social body ever since the constitution of separate organs of overall decision making across history in the great variety of state formations.

In truth, we either have that substantive—i.e. not vacuously formal and in reality nullified—decision making power or not. Talking about only degrees of it is self-contradictory, as it would be if we tried to do the same in the case of “degrees of substantive equality.” For if we have only some degree of substantive decision making, the question inevitably arises: who has the rest of it? And the meaning of that question in the form of a self-evident answer is that whoever might have it, we do not have it! Indeed, in actuality we do not have it because—as a matter of the structurally entrenched systemic determination of our antagonistic social metabolic order—the state itself usurps that power of decision making, in its superimposed modality of functioning as the overall command structure of societal decision making. Moreover, what makes matters even more difficult in this respect is the historically determined necessity whereby usurping the power of overall decision making by the state is not an arbitrary process of “state excesses,” corrigible by some enlightened intervention in the political domain itself, as even the best Liberal Political Theorists diagnosed it in vain. For the duration of its historical necessity—defined by the unfolding historical development itself as a “vanishing necessity”38—the state is mandated to be the usurper of overall decision making by the structurally entrenched antagonistic determinations of our historically constituted social metabolic order. That is what needs to be radically altered at its causal foundations if we want to envisage a historically viable solution to our potentially all-destructive antagonisms.

All state formations in history asserted that power of overall decision making over substantive matters, in a correspondingly substantive way, no matter what might be the “formally equitable” ideological rationalization and legitimation of their actions. It is also characteristic of all state formations in history that the violent antagonistic confrontations over their rival borders was endemic to their mode of ultimate decision making. Capital did not invent wars, just as it did not invent the exploitation of surplus labor. But it certainly created the conditions of absolutely prohibitive global wars not only in the form of its now readily available all-destructive weaponry but primarily through the materially invasive globalization of its reproductive structures that cannot be matched by some global state formation. The historic anachronism of the state itself on the persistent antagonistic material ground of the capital system is the necessary concomitant of such developments.

Between the two global wars in the twentieth century one could still dream about the efficacy of some kind of Kantian League of Nations in the service of “Eternal Peace”, but not for long. Now the “realists of power” can only project the nightmare solution of a global coercive state.

Is there another way by radically overcoming the antagonistic destructiveness itself when their perpetuation under superimposed state legitimacy becomes suicidal to humanity? That is the absolutely vital question that needs in our time an urgent answer.

Notes

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, p. 235.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, p. 269.

- ↩ For instance the Liberal State, or the Fascist State, or for that matter the post-revolutionary Soviet-type State.

- ↩ Associated with Giovanni Giolitti’s Liberal Government in Italy in 1922.

- ↩ See, for instance, Hegel’s far-reaching arguments on the Nation State.

- ↩ For an outstanding pioneering work on the socialist left published on this subject see John Bellamy Foster’s book, Marx’s Ecology: Materialism and Nature (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000); see also John Bellamy Foster Brett Clark, and Richard York, The Ecological Rift: Capitalism’s War on the Earth (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2010). On the latest phase see the powerfully argued and richly documented book by Ian Angus, Facing the Anthropocene: Fossil Capitalism and the Crisis of the Earth System (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2016).

- ↩ This lecture was written in 1970 and delivered at the London School of Economics on 26 January 1971.

- ↩ MECW, vol 5, p. 52.

- ↩ Ibid., p. 73.

- ↩ Ibid., p. 87.

- ↩ Naturally, Marx and Engels were avid readers of The Economist.

- ↩ Marx, Letter to Engels, 8 October 1858 (MECW, vol. 40, p. 347). Italics added.

- ↩ Engels made it clear in the Preface of his book against Dühring that the reason why he wrote it was because “people were prepairing to spread Dühring’s doctrine in a popularized form among the workers.”

- ↩ Marx, Letter to Kugelmann, 27 January 1870.

- ↩ Eduard Bernstein, Evolutionary Socialism, New York: Schocken Books, 1961, p.213.

- ↩ Ibid., p. 209.

- ↩ Ibid., p. 212.

- ↩ Ibid., p. 213.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ That is the danger now anxiously highlighted with reference to the increasing threat to the earth system itself under the conditions of the “anthropocene.”

- ↩ Martin Wolf, Why Globalization Works? The Case for the Global Market Economy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004, p. 320.

- ↩ Quoted from p. xiii of G. C. A. Gaskin’s Introduction to the Oxford University Press edition of Leviathan by Hobbes, published in 1991.

- ↩ See C.B. Macpherson’s famous book with this title.

- ↩ “Le tiers état.”

- ↩ The “États Généraux.”

- ↩ Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, pp. 199-200.

- ↩ Ibid., p. 200.

- ↩ Rousseau, A Discourse on Political Economy, London: Everyman, p. 264.

- ↩ Roussau, The Social Contract, Everyman edition, p. 42.

- ↩ Rousseau, Ibid., p. 37.

- ↩ Rousseau, A Discourse on Political Economy, p. 254.

- ↩ Rousseau, The Social Contract, p. 19.

- ↩ Kant, “Eternal Peace,” pp. 448-9 of Kant’s Moral and Political Writings, New York: Random House, 1949.

- ↩ Ibid., pp. 452-3.

- ↩ Kant’s Moral and Political Writings, New York: Random House, 1949, p. 418.

- ↩ See passage referred to Note No. 47.

- ↩ Kant’s Moral and Political Writings, p. 417.

- ↩ “eine verschwindende Notwendigkeit,” Marx, Grundrisse, p. 832.