Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, journalist, and Marxist intellectual. Among numerous books and articles, Prashad’s The Darker Nations stands out for its thorough account of Third World organizational efforts during the 20th century. Today, he is chief editor of LeftWord books and heads up the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. Last week, Prashad was in Caracas for the International People’s Assembly and found time to respond to some of our questions about the history of internationalism and how to do solidarity with Venezuela and other countries under imperialist siege.

There is a long history of international solidarity, but as far as South‐South solidarity goes, one important landmark is the Non‐Aligned Movement which from 1961 on brought together governments from what we now would call the Global South. Could we talk about what that legacy stands for today?

There are two reasons why we should understand this. It’s important to see that when Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote the “Communist Manifesto” in 1848, they wrote “Workers of the world, unite!” But in 1848, the workers of the world couldn’t communicate with each other. In fact, the first telegraph between India and Britain only came in 1870. So it would be a bit silly to look back and say about the First International of workers set up in London or even the Second International, that they were really internationals. After all, in the colonized parts of the world, workers movements really didn’t get going until the second half of the 19th century and later.

So it’s really important that the story of internationalism in the South not be too enthusiastic about small connections in the “ancient time.” By the “ancient time,” I mean the 18th and 19th centuries. All that would be quite silly, because the real connection begins in the period right after the Russian Revolution. Strikingly, the Russian Revolution, the USSR, took a decision that was quite out of time. In 1919, a hundred years ago in March, [it] invited people from across the world to create the Communist International. The Communist International was made up not only of European trade unionists, radicals, and so on, but also people from as far away as Argentina and Puerto Rico. Initially, it involved mostly the Western Hemisphere, and the various parts of the former Russian empire that had been colonized… Turkmenistan and such.

Then in 1920 [in the Second World Congress of the Comintern) many more people came from around the world (and you know, the real heir to this movement was the Tricontinental Conference that met in La Habana by the late 1960s).

In 1928, the bourgeois anti-colonialists met in Brussels in the League Against Imperialism meeting. I’m saying all this to point to the fact that the history of international struggles–of solidarity with and among people who had been colonized–is only about a hundred years old. A hundred years in the large scheme of things is not a long time. So I don’t think we are ready to be judged regarding the utility and value of anticolonial solidarity across boundaries.

It is of course important to say that, from the 1950s, when new states emerging out of colonialism like India, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, and Indonesia created the Non‐Aligned movement in Belgrade in 1961, that was a different kind of process, because it involved countries: it was an intergovernmental movement. They had now taken state power, and they were trying to change the routines and institutions of the world order. It was a much different scale of discussion. They had an incredible vision for an alternative, it was called the New International Economic Order, which was passed by the UN General Assembly in 1974.

From left to right Jawaharlal Nehru, Kwame Nkrumah, Gamal A. Nasser, Sukarno, Josip Broz Tito, founders of the Non-Aligned Movement. New York, September 30, 1960. (Archive)

Imperialism and especially U.S. imperialism consistently tries to undo these South-South alliances. We have seen how U.S. imperialism operates in Latin America and its attitude toward Venezuela particularly aggressive now. Can you tell us something about how imperialism works in the broad sense and then move into the particulars of the Venezuelan situation?

Imperialism is not a static phenomenon. What we had in the 19th century and into the early 20th century is different from what we have now. At that time, production was mostly inside nations. You had the Ford Motor Company located in the United States in competition with Daimler located in Germany, and most Daimler cars were built in Germany, while most Ford cars were built in the United States. They were competing for resources in third or fourth or fifth countries and for markets and finance, etc. That was a form of inter‐capitalist rivalry, and it pushed countries to use their political, military, and economic power to get an advantage over other countries. That was the classic form of imperialism in the old days.

From the 1960s onwards, the old factory form began to dissolve. You saw factories being disarticulated and the emergence of the so called “global commodity chain.” General Motors began to produce most cars outside of the U.S. German cars were as often finished in Germany as in the United States…The whole structure of world production changed.

This had an impact on imperialism, because from the late 1960s onwards [there emerged] a much closer alliance between what we call the Triad: the United States, Europe and Japan. The Triad didn’t come together with equanimity –they didn’t agree on everything–but there was a certain understanding that the U.S. was the first among equals; that new trade regimes had to be created and enforced; and that Third World [projects] such as the New International Economic Order had to be destroyed.

It was in this realm that imperialism sharpen its teeth. Now aerial bombardment was not necessary. It all came in the writing of trade laws, [in determining] how finance should operate and money should move. An entire infrastructure was created almost behind the scenes by a group of seven countries, using the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs [which spawned the World Trade Organization in 1995]. In the 1980s, they imposed new regulations on property rights.

All this narrowed the ability of Third World countries to develop, to be able to trade with each other, and exercise their right to finance. A new set of “institutional asphyxiations” were created by imperialism. It was very smart, because now you didn’t have to show your gun. It was there, but it was hidden, because you now exercised power by saying “Sorry, we are not going to finance you,” particularly after the debt crisis in the early 1980s.

Countries like Venezuela are so vulnerable… In 1974, when Venezuela “nationalized” its oil resource, it actually didn’t do it. What actually happened is that the companies told the government: “You nationalize the oil, because we don’t want to deal with it anymore. We don’t want to invest in your country or take the risk. You invest and take the risk. We just want the profits.” That is the new structure of imperialism.

That brings us to the present. Right now, it seems like there is an intense effort to strangle Venezuela’s economy and topple the government (to say nothing of killing off the socialist project). I would like your perspective on both the risk of direct military intervention in Venezuela and on other less visible forms of violence, like economic sanctions.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, the United States actually began to feel that there was going to now be another century of complete domination [that it would lead] on behalf of the Triad. Actually, the U.S. is quite generous to its Triad partners: it’s not as if it wanted everything for itself. It wanted growth of the corporations, because that was seen as benefiting the United States and its allies. They thought that what was coming was a hundred years (who knows even a thousand years!) of capitalism dominated by the U.S. and its allies…

But [instead of that simple capitalist success story] there was enormous demoralization after the collapse of the USSR… There was a huge demoralization, because so many of the countries that had previously experimented with socialism and had transitioned, now began to collapse one after the other into debt, disorder, and so on. So the U.S. began to talk about a few countries that it called “rogue states” which needed to be taken out. Then after that would begin the thousand year rule! They identified Iran and North Korea, among others (you know, any country that seemed odd and wasn’t allowing the trade order determined by the World Trade Organization to manage things).

Of course, what began to be evident is that there were contradictions. These contradictions are uncomfortable–they are in bad taste!–such as the Irakis saying “Look, we fought the war on your behalf against the Iranians, and now we want payment for the destruction of our country.” Then they invaded Kuwait, and that bothers the Triad, so it goes into Iraq. [Another example is] Yugoslavia, where you see that, as the cement of socialism began to break down, very toxic forms of nationalism began to appear. Then Yugoslavia was bombed into destruction.

The wars continued, bewildering wars. They were in principle wars to finish off the remnants countries–not socialist countries by any stretch of the imagination–but countries that were resisting the will of the Triad led by the U.S. It is wrong to idealize these countries just because they were being bombed by the U.S. Some of them had very dystopic internal relations (even if they were being attacked for other reasons). It was a surprise, but we understood that the war was a way of saying: “Let’s get rid of the walls around Yugoslavia, and let’s open it up to the IMF and the World Trade Organization. Let’s get those markets and those workers…”

The United States got embroiled in the wars on Iraq and Afghanistan in the early 2000s. They took their gaze away from South America. They lost sight of the plot and didn’t see what was happening. In one country after another, diverse social movements, indigenous peoples, and popular masses turned to elections. And in one country after another, they elected left-wing people!

Honestly, if the U.S. hadn’t been so involved in Iraq and Afghanistan, they might not have allowed this to go all the way. Afterall, they do have this idea–which has come up again recently!–that this is their backyard. But by the time they turned their gaze back here in 2002 and tried the coup in Venezuela, it was already too late. Although there are differences between the Workers Party [PT] in Brazil and the experiment in Venezuela (such as working at different paces) nonetheless they were on the same page.

In Venezuela, Chavez [realized] that you cannot build a new project inside a country: it has to be regional, and you need new trade policies. Venezuela understood how imperialism was working: it was the imperialism of finance and trade, and so it attempted the ALBA project involving regional governments and states.

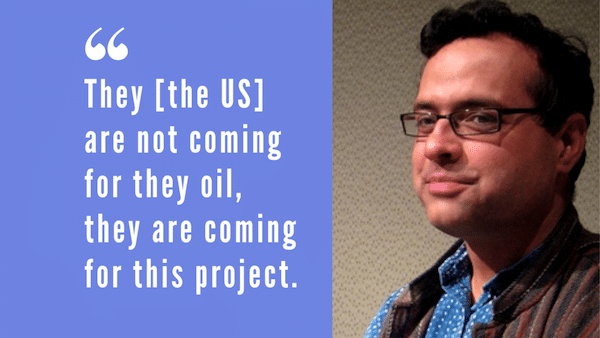

The U.S. attempted to break that project many times. Look, Venezuela doesn’t have the kind of oil that the U.S. needs and desires. They are not coming for the oil resources! They are coming for this project, and they did a very good job. Honestly, the most impressive coup d’etat that they managed in this period of social media was the [2009] coup in Honduras. There was also, earlier, the coup d’etat in Haiti, where they just absented Aristide twice, and in the rest of the continent, they pushed [the leftist wave]back in little by little.

But it wasn’t just U.S. imperialism, and not being aware of that is one of our weaknesses. It’s also that new social forces came in that the left was not fully cognizant of. For example, pentecostalism and various [other] forms of aspirational desire from below. Things were being reshaped and people were moving in directions that were outside of the ideology of the new Pink Tide and the Bolivarian Project.

I think there are two big dynamics that weakened this project. It wasn’t just imperialism. There were these internal developments that were contrary to the dynamic of a strong left, and, of course, you have the collapse of commodity prices. But what I want to highlight here is that it wasn’t the collapse of commodity prices alone that creates this problem.

There are a couple of other things that I would like to say on this subject. One is that socialism takes time in a poor country, and this is a poor country. It has never been a rich country. It is a poor country with a lot of oil, just like Nigeria. It’s rich in resources, but very poor in terms of the distribution of wealth and aspirations and hope and so on. Socialism takes a long time, and basically ten years is not enough. ..

Thomas Sankara used to say, “He who feeds you, controls you.” But this country imports most of its food. There was no freedom yet. It was going to take thirty, forty, fifty years to get there. Capitalism took hundreds of years to develop. Socialism is always attacked within two, three, four, or five years, and not just by the capitalists, but also by people on the left who get impatient and angry, because it doesn’t meet their own dreams and utopias. It’s a very ugly process, because you are desperately trying to create new forms, and in the meantime you must be sure that people are not hungry.

That is the first point. The other one is a political question: the United States was very craftily able to set legal boundaries around countries, where they said, “Well, we are going to sanction you because you did this wrong.” Obama’s Decree in 2015 opened the door, and then from that door they add another sanction and another, and more and more. And since they control money, its movement, and how you are going to buy and sell your own goods, then you are really caught in a vice, and nobody is going to come to liberate you.

If tomorrow this government falls and an American-backed government comes in, what will the Chinese and the Russians say? Pay us back in cash. The truth is that Venezuela is not in good shape, whether the Bolivarian government remains or an American puppet government comes in. The Americans will not have the money to pay back the Chinese and Russians. That is just not going to happen! If the [newly installed] government were to say that we need to renegotiate our loans, that is a bad precedent, so Americans don’t want that. You’ve got to face up to the fact that there are some serious economic challenges, and it’s very tragic that the oligarchy and others don’t see that. They are being reckless with their own country. I think, they will pay a huge historical price for that recklessness.

Venezuela is highly vulnerable, as it is dependent on imports for most food items, including corn and other staples of the Venezuelan diet. (Archive)

Finally, I would like to ask you about international solidarity these days? How should it be done, especially in relation to Venezuela?

Solidarity with the Bolivarian Process has to begin by demanding the end to all interference. Now, interference is a complicated word under the new imperialism. It means no military intervention, that is one point. But does it mean that there should be no embargo? Yes, that is another point. No economic sanctions? That is another point. Also, finances should not be blocked, and Venezuela’s own money should be available to it. Of course, all that is important.

But I’m saying there is more than that: solidarity must help countries have food security, total independence in relation to food. You know, Cuba needs solidarity to help it produce grains, and it doesn’t produce enough potatoes either, nor does it produce anywhere near what it consumes in terms of wheat or rice. These problems are solved through human connections. We have to really work together to provide food security. Hunger is a weapon often used by imperialism. They make you hungry, and then they tell you, “Take the aid.” It’s very crafty, so this is the thing that has to be overcome.

This is not news to anybody. Chavez spoke about the problem of food all through his political career. It was very important for him to think about how to feed the country. Like, is it possible to feed this country with domestic grains? Also the problem of feeding animals. He talked about this stuff all the time. Fidel, towards the end of his life, had this dream of creating organic food for animal feed that is produced now in Venezuela. These kinds of options must come to be. In that sense, solidarity should not be thought of as a slogan, solidarity is a process. You have got to build solidarity by providing interesting new thinking about how to solve problems of hunger and how to organize society.