Frida Kahlo was undervalued in her time, but today her art, her fashion and her politics are commercialised worldwide. Here, Mike Gonzalez looks back at the art and politics of a woman who worked hard to curate her own persona, translating her pain and passion into personal and political expression.

Frida Kahlo was not a heroine, nor was she a victim. She painted her pain and her suffering but she defied and overcame them in the very act of painting. She was also more than her suffering; an artist who explored her own history, the history of her own country—its past and its future—and who understood who its enemies were.

The blue house

I began visiting Frida Kahlo’s house in Coyoacan, in Mexico City, in the seventies. It was a tranquil place. Behind its blue washed walls were her home and studio and a courtyard full of objects from popular culture—like the papier-mâché figures called ‘Judases’ which are traditionally burned at Easter. There were stone figures from a pre-Hispanic past.

In her kitchen her collection of hand made pottery was matched on an opposite wall by her retablos, naïf paintings painted on tin or wood which expressed the gratitude of ordinary people who had escaped, as if by a miracle, some personal or family tragedy. But bizarrely, in her studio, her last painting occupied an easel—it was a portrait of Stalin.

Downstairs, looking on to the patio, was the bedroom she shared with the muralist Diego Rivera. It was hard to picture her tiny fragile body beside the sheer bulk of her husband. On the pillows were delicate lace covers, embroidered with their names by Frida.

In all its curious contradictions, the blue house was itself a portrait of Frida.

The icon

Today the house is a magnet for visitors in pursuit of an icon, yet in the seventies she was a neglected and undervalued artist, more famous for being the wife of Rivera than for her own work. That has certainly changed.

In the early eighties, Frida was ‘discovered’ by art critics in Europe and the U.S. The first exhibition of her work opened in London in 1982 and a year later, Hayden Herrera’s biography was published. By the end of the eighties both Vogue and Elle published photographs of models wearing the clothes for which she was so well known; she was presented as the ‘spirit of Mexico’ and the ‘romance of Mexico’.

There were multiple ironies here. The magazine treatments are revealing. The perfect bodies of the models were very far from Frida’s broken body—which she concealed beneath her long skirts. If she did represent the ‘spirit’ of Mexico, it was certainly not a romantic vision. And in any event, what attracted the critics was her marginality—as a woman, as a Mexican, as a person in pain. It was, after all, a time when the art market went in search of outsider art—graffiti, the art of Africa, experimental film.

Herrera’s biography encouraged a view of her art as a direct expression of her biography. Her Mexican-ness made her an exotic figure, her personal history a victim.

It was a deep misreading, in my view.

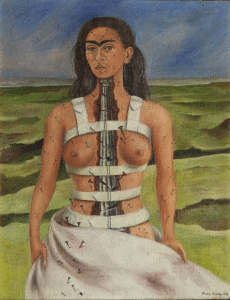

The damaged body & the divided self

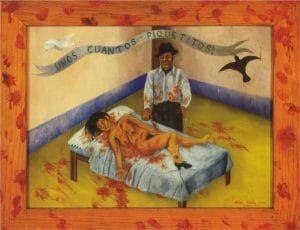

About half of Frida’s paintings are self-portraits that often expose her to prurient curiosity, a fascination with her damaged body which she portrayed with a cruel self-deprecation, like ‘A few small nips’ or ‘The broken column’. Herrera told the story of her painful growing up. Early in life she contracted polio which left her with a withered leg. Then, at sixteen, she was involved in a streetcar accident which left her with a broken spinal column, multiple broken bones and—most brutally—a metal rail penetrated her back and through her vagina. The consequence was a life of endless clinical interventions, and imprisoned in metal corsets and leg braces. Many of these infernal devices were displayed in a bizarre recent V and A exhibition devoted to her dress and her orthopaedics.

The irony, I think, is that while Frida had the enormous courage to examine her pain and its formative influence on who she was, her manner of dress was—in part but not only—a way of concealing that other self, of denying her ravaged body control over her selfhood. She acknowledged the connection between her suffering and herself unblinkingly—but she never allowed herself to become her pain.

Frida was always aware of her body, her appearance and the ambivalent identity it allowed—even before her accident. Her father, Gustavo Kahlo, was a photographer of Hungarian origin, a portraitist in the formal 19th century studio sense. Yet in family portraits Frida appears—not for the last time—in masculine dress. If it was then a disguise, a game of gender-shifting, then that became a doubly poignant and powerful exercise in performance in her later life.

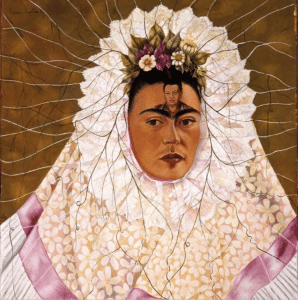

Her clothing was much more than a simple cover, a veil. It made a more profound and defiant statement. The long skirts and embroidered blouses she wore (as her mother had) were not merely generically Mexican. They were Tehuana, the clothing worn by the women of the intensely matriarchal indigenous community of Tehuantepec in Mexico’s south. It was a mark of identity rather than a mask, as a woman and as a Mexican. Her jewellery was often the heavy jade products of indigenous tradition—and part of the wider statement.

These are the ‘The Two Fridas’—the broken and the whole, conventionally dressed and wearing the Tehuana costume.

In painting herself she was doing more than filling her solitude as she herself suggested. She was exploring the experience of women and of Mexico. The injuries were real enough, but they were symbolic too of the experience of women.

In her time

In 1927, when Frida met Diego Rivera, she had already joined the communist party. Rivera himself was engaged in the painting of the great murals in Mexico City that had been commissioned by then Minister of Education, Jose Vasconcelos. The major series in the Education Ministry itself were part of a rewriting of Mexico’s history, a history which until then had been written by the colonial victors and made indigenous Mexico invisible.

In 1910 a political revolution against the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz was the spark that set in motion a deeper social revolution, in particular a peasant uprising under the leadership of Emiliano Zapata and a popular rebellion in the north led by Pancho Villa. In Baja California, the anarchist Flores Magon brothers attempted to drive forward a militant workers struggle. It was a complex movement, formally brought to an end by the 1917 Constitution promoted by an emerging ruling class dedicated to building a new, independent nation-state at the expense of those who had made the grass roots rebellion. But the formation of that state demanded a new, nationalistic ideology which would be defined as a Mexico of indigenous roots. The Muralist movement, and most particularly the work of Rivera, set out the new narrative on the walls of Mexico’s public buildings. Public spaces became the canvases for public debate.

The language of anti-imperialism and national identity, however, quickly became a veil for corruption and a weapon in a power struggle (as so often happens). Yet the vindication of indigenous Mexico, the recovery of its great architectural sites, the disinterring of the many references to that past buried in popular culture, its philosophical heritage in the cult of death and so on was deeply significant. Frida’s art echoes popular art in multiple ways and is at every level a vindication of her identity as a Mexican woman.

Frida and Diego

It would be an understatement to describe their relationship as stormy; it was volcanic. Rivera was an egomaniac, a huge man with a voracious sexual appetite. Frida’s famous portrait—‘Diego on my mind (Self-portrait as Tehuana)’—of her face within a headdress with Diego’s face embedded in it has been seen by many as undermining Frida’s feminist credentials. Her love for Diego, the archetypal dominant male, was undeniable. He was notoriously unfaithful—conducting an affair with Frida’s sister, in the house. Frida’s sexuality has been a source of curiosity for the icon-seekers; was she bisexual, was she promiscuous. She was clearly both, and proudly so. When Leon Trotsky, recently arrived in Mexico with Rivera’s support and fell in love with Frida, the victim was his wife Natalia who had accompanied him throughout his terrifying enforced exile across the world, pursued by Stalin’s thugs who eventually killed him. Frida clearly felt no female solidarity with Natalia, but certainly felt flattered by the attentions of this extraordinary revolutionary. There clearly are judgments to be made, but the absence of error or contradiction as a condition for admiration would leave us very few people to look up to. What is clear is that, despite her broken body, Frida was a passionate sensuous woman who attracted much more than simply sympathy for her pain—she was loved in her turn by men and women.

Beyond her story was her imagination, her vision and capacity as an artist which is always in danger of disappearing beneath endless personal anecdotes, or into the enormous shadow of Diego Rivera. But she was an artist in her own right, and her work carried her out of her individual life into the realm of the social imagination and cultural struggle.

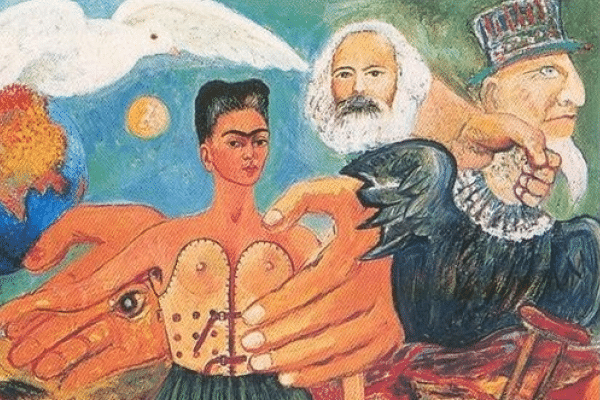

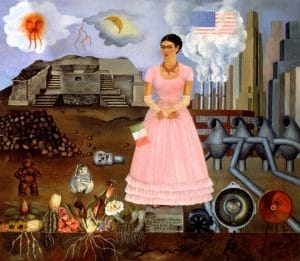

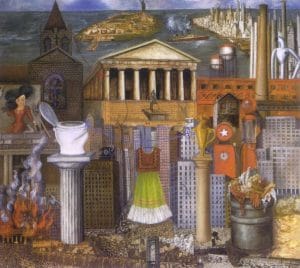

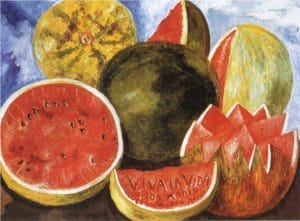

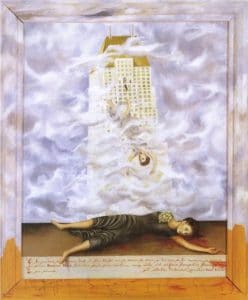

She was, after all, a communist—almost certainly a Stalinist in her political views but an anti-imperialist in a profound sense. It is worth considering two of her lesser known paintings, ‘At the border’ and in particular ‘My dress hangs here’. Painted in the 1930s, when she accompanied Rivera to the United States, they are clear cultural critiques. The border is the frontier with the U.S. To one side is a North America of skyscrapers, the Lincoln Memorial and everywhere the dollar signs; on the other is the colour, the sensuality (consider her painting ‘Viva La Vida Watermelons’, actually her last before her death), the powerful mythology of Mexico. On that same border her dress hangs proudly between a toilet bowl and a golf trophy—to one side a tattered portrait of Mae West, a cross wrapped in a dollar sign and the other pseudo-relics of an industrial age. It is witty, nostalgic, and angry—as always a statement of personal rage and pain rather than a formulaic political statement.

To bring these themes together is a lesser known painting but a very dramatic one. ‘The suicide of Dorothy Hale’ records the death of an American socialite abandoned by her husband, who killed herself after a party she was encouraged to hold as consolation for her distress. Here too the dress matters; it was a designer dress that cost a thousand dollars. We see her lying on the pavement, still wearing it, with the skyscraper from which she jumped behind her. It was not a piece of reportage but a statement about the position of women. Unlike Rivera’s work, her art was intimate, often small, and often intensely personal.