Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

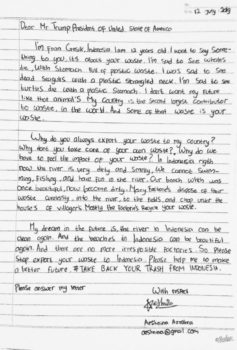

On 12 July 2019, a twelve-year-old girl from Gresik (Indonesia), Aeshnina Azzahra, wrote a letter to U.S. President Donald Trump. The letter was delivered to the U.S. embassy in Jakarta and released to the press. ‘My country’, she wrote, ‘is the second largest contributor to waste. And some of that waste is your waste’. Then, she asked three powerful and sincere questions: ‘Why do you always export your waste to my country? Why don’t you take care of your own waste? Why do we have to feel the impact of your waste?’

Trump has made nasty remarks about how Asian countries are the great polluters of the planet. Trump, in his shudderingly ignorant way, said that the United States of America would use its power to prevent Asians from destroying the planet.

Malaysia’s government reacted immediately to Trump’s comments. They blocked ships carrying trash from the United States from entering Malaysian waters. The future of these ships, and their toxic cargo, is not clear. There are unknown numbers of ships across the oceans carrying trash from the United States–and other Western states–towards countries that are forced to buy this trash and that do not have the technology or will to process it.

Twelve-year-old Aeshnina Azzahra worries about whales that are strangled by plastic waste. There are 8.3 billion metric tonnes of plastic waste that form a noose around the planet. Of them, 150 million tonnes are thrown into the oceans. Most (78%) of the plastic waste from the United States goes to countries that burn it.

Waste poses a serious problem. A World Bank report estimates that humans produce 2.01 billion metric tonnes of trash per year. By 2050, that figure will rise by 70% to 3.4 billion metric tonnes. Of this trash, only 13.5% is recycled, while only 5.5% is composted. Thus, 81% of this trash is discarded in landfills or incinerated. If we continue at our current pace, we will need new planets as landfills.

Members of the Kōtō ward assembly checking garbage trucks entering their neighbourhood, 22 May 1973. Photograph by Mainichi Shimbun.

But there is a geography of imperialism to trash. This is something that twelve-year-old Aeshnina Azzahra knows. Her three questions are sharp and clear–why does the West export its trash to the poorer nations? It is not precise to say that ‘humans’ produce trash. Certain humans produce more trash than others. The United States, with 5% of the world’s population, produces 40% of the world’s garbage. In 1991, the World Bank’s chief economist Larry Summers (later U.S. Treasury Secretary) wrote a memorandum which made the following elegant point: the West has a surplus of money and a surplus of trash, while the poorer nations have a deficit of money and a deficit of trash; why not, therefore, allow the poorer nations to be paid to take trash? The scale of garbage production–geometrically higher than it was in pre-capitalist times–has resulted in the commodification of trash. Major global businesses occur to dispose of the trash, including through the export of this trash from one part of the world (the West) to another (the poorer nations).

Summers’ memorandum came at a time when the countries of Africa, Asia, and Latin America had started to ban the import of trash. In 1988, the Organisation of African Unity called for a ban, which came into effect in 1991 with the Bamako Convention. Sixty-nine countries of Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific had already banned waste imports with the Lomé Convention of 1989. It was to this tide against the trade in trash that Summers responded with his racist (and deeply anxious) memorandum.

The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP)–set up in 1972–has as part of its mandate the surveillance of transboundary traffic in garbage. Multinational corporations that trade in chemicals and waste have hampered its work. Greenpeace took up the issue of the garbage trade with vigour in the 1980s, forcing it on the agenda, which resulted in the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal (the UN treaty was passed in 1989 and adopted in 1992).

In 1994, at the second Conference of Parties to the Basel Convention, the G-77 states (the Third World bloc in the United Nations) were joined by the European Union to ban the trade of hazardous waste from the countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)–comprising the West and Japan–to non-OECD countries. Australia, Canada, and the United States lobbied hard against this ban. In January 2018, China banned all imports of garbage, which now went in greater volume to Indonesia and Malaysia–where the current fracas continues.

Between Friedrich Engels’ Condition of the Working Class in England (1844) and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), there has been widespread awareness of the toxic side of capitalist development. But workers and peasants didn’t need Engels’ or Carson’s analysis to explain the nasty effluents from factories or the terrible violence of chemical pesticides and fertilizers.

The garbage that rots on the surface of the earth is the appearance of the problem. The essence of the problem is the requirement of our socio-economic system to endlessly sell commodities, then decrease their lifespan, so that more commodities are bought to replace them, and so that the discarded commodity joins its brethren in the mountains of trash on land and the islands of trash in the oceans.

In 1955, the Journal of Retailing noted that the system required that ‘things be consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever increasing pace. We need to have people eat, drink, dress, ride, live, with ever more complicated and, therefore, constantly more expensive consumption’. This is what Vance Packard, in The Waste Makers (1960), called ‘planned obsolescence’. ‘We make good products’, Packard wrote. ‘We induce people to buy them, and then next year we deliberately introduce something that will make those products old-fashioned, outdated, obsolete’.

Garbage, from the standpoint of capitalism, is an ‘externality’. Capitalist firms plunder nature for resources, and dump waste back into the earth. The costs of this plunder and this waste are not to be factored in to the balance sheets of the firms. These are considered to be ‘external costs’. The velocity of the production of commodities, as part of the necessity for endless accumulation of profit, generates theories such as ‘planned obsolescence’, setting in motion the creation of trash. In the West, computers used to last for seven years, phones for five–now, computers are replaced every two years, phones every twenty-two months.

Procedures to diminish the volume of trash–by reuse and by recycling–are minimal. Social life, encrusted with commodification and consumerism, cannot be easily pivoted to new forms. Prognosis for less growth where there is tremendous waste is low. There is, meanwhile, already pressure on spaces of deprivation that are receiving rather than producing the majority of the world’s waste to not produce trash. This is like the debate over climate mitigation–the poor are being told to tighten their belts, while the rich continue to spew carbon into the atmosphere.

The 1987 UN World Commission on Environment and Development–the Brundtland Commission–defined the concept ‘sustainable development’ as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Certainly, by now and from overuse, the term ‘sustainable development’ has the tincture of meaninglessness. But when it was coined it did mean something. It meant that ‘development’ pathways should be conceptualised that allow the deprived to access more than basic needs, while the privileged should lessen their footprint on the planet. That meaning, contrary to the logic of capitalism, needs to return to our debates.

Please read Aeshnina Azzahra’s letter. Here is the voice of another young person who is deeply worried about the fate of the earth. She needs her voice amplified. She needs billions of us to refuse to accept the world as it is, a world that is choking on its own refuse. She, like the whales, wants to breathe.

Often people ask: could you recommend a place for news? This is a difficult question, made more difficult as the media gets less and less free of money and State power. Based in New Delhi (India), is People’s Dispatch, which has now turned one. People’s Dispatch, which began in Latin America as The Dawn News, is a news source and a news wire for people’s movements. It takes a stance on behalf of the people’s movements, and reports on protests and campaigns that emerge from them. Please visit their website and follow them on the various platforms of social media.

Warmly, Vijay.

PS: each newsletter, in English, French, Portuguese, and Spanish is uploaded onto our website. All our materials can be read there.