Killer Heat in the United States: Climate Choices and the Future of Dangerously Hot Days (2019) – Full Report

Extreme heat is poised to rise steeply in frequency and severity over the coming decades, bringing unprecedented health risks for people and communities across the country.

County-specific results are available for each of the 3,109 counties in the contiguous United States for all extreme heat thresholds and scenarios included in the analysis.

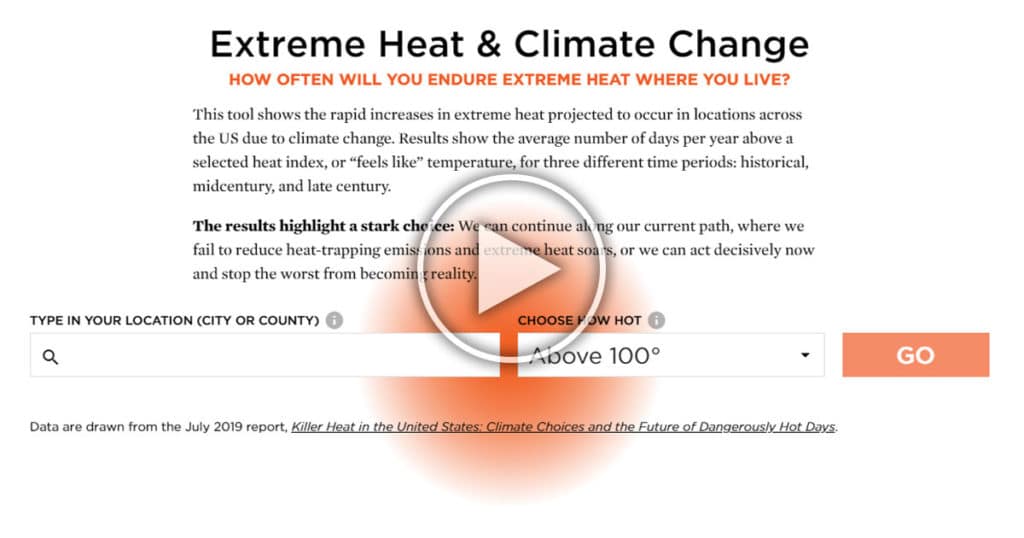

Explore interactive maps of the analysis

The United States is facing a potentially staggering expansion of dangerous heat over the coming decades.

This analysis shows the rapid, widespread increases in extreme heat that are projected to occur across the country due to climate change, including conditions so extreme that a heat index cannot be measured. The analysis also finds that the intensity of the coming heat depends heavily on how quickly we act now to reduce heat-trapping emissions.

The results highlight a stark choice: We can continue on our current path, where we fail to reduce emissions and extreme heat soars. Or we can take bold action now to dramatically reduce emissions and prevent the worst from becoming reality.

NEW (July 26, 2019) — Congressional district-specific information (interactive map)

Data and fact sheets for all 433 Congressional districts in the contiguous US

Regional and state-specific information (press releases)

Northeast (CT, DE, DC, ME, MD, MA, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT, WV)

Southeast (AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MI, NC, SC, TN, VA)

Midwest (IL, IN, IA, MI, MN, MO, OH, WI)

Southern Great Plains (KS, OK, TX)

Northern Great Plains (MT, NE, ND, SD, WY)

Southwest (AZ, CA, CO, NV, NM, UT)

Northwest (ID, OR, WA)

National information (press releases)

Supporting methodology and analysis

Environmental Research Communications research article

Download data for all locations and scenarios included in this analysis (Excel)

By region — By state — By county — By city/urban area — By population exposure

Dangerous heat

For this national analysis, extreme heat is measured according to the heat index, the combination of temperature and humidity that creates the “feels like” temperature.

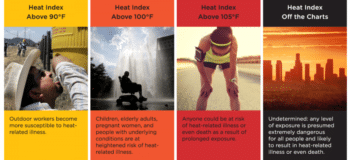

The analysis includes four different heat index thresholds, each of which brings increasingly dangerous health risks: above 90°F, above 100°F, above 105°F, and “off the charts.” (Off-the-charts days are so extreme they exceed the upper limits of the National Weather Service heat index scale, which starts topping out at or above a heat index of 127°F, depending on the combination of temperature and humidity.)

The report features three time frames—historical, midcentury, and late century—and three different scenarios of climate action.

Photo- AP:John Locher

Location-specific results can be found using the interactive tool above. Complete findings are available in the full report.

The health risks of extreme heat

When extreme heat conditions prevent our bodies from adequately cooling, our core temperatures rise, especially during periods of prolonged exposure.

Heat stress and then heat exhaustion follow as body temperature rises upward. Once the body’s core temperature reaches 104°F or higher, heat stroke—the most severe heat-related illness—can result.

Extreme heat exposure affects people differently depending on their health and environment. As illustrated below, certain groups of people become more susceptible to heat-related illness as the heat index rises.

Learn more about how to prepare for and deal with extreme heat: 5 Great Public Health Resources for Dealing with Extreme Heat.

Implications and solutions

The implications of this analysis are profound: in many places, extreme heat will lead to an increase in deaths or illnesses, disrupt long-standing ways of life, force people to stay indoors to keep cool, and perhaps even drive large numbers of people away from areas that become too unpleasant or impractical to live.

To prepare for the coming heat, we must take steps to keep people safe.

Photo- AP:Daily News, Miranda Pederson

This includes creating heat adaptation and emergency response plans; expanding funding for programs to provide cooling assistance to low- and fixed-income households; directing the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to set up protective occupational standards for workers during extreme heat; requiring utilities to keep power on for residents during extreme heat events; and investing in research, data tools and public communication to better predict extreme heat.

At the same time, we must also take bold action to dramatically reduce heat-trapping emissions and limit the frequency and intensity of extreme heat events in the future.

This includes transitioning our energy system to low-carbon energy sources; ramping up energy efficiency; electrifying as many energy systems as possible across the transportation, buildings, and industrial sectors; and investing in land use and forest management practices that help store carbon in soils, trees, and vegetation.

To give ourselves the best chance of keeping global average warming below 3.6°F (2°C), in line with the goals of the Paris climate agreement, the United States must invest in these and other bold solutions alongside robust global action, to get to net-zero carbon dioxide emissions by midcentury.

We have no time to waste to prevent an unrecognizably hot future from becoming reality.

We must act now to address the climate crisis.