Richard Reeves is right about one thing: time is crucial to capitalism’s legitimacy. The premise and promise of capitalism are that the future will be better than the present. And “if capitalism loses its lease on the future, it is in trouble.”

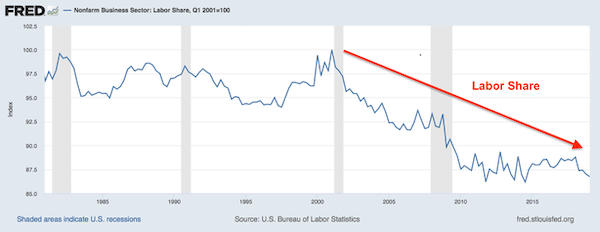

The fact is, things are not getting better for the vast majority of American workers. They’re falling behind. For example, as is clear in the chart above, the labor share in the U.S. nonfarm business sector has fallen more than 13 percent since early 2001—and there’s no indication that trend will be reversed anytime in the foreseeable future.

Time is clearly running out on capitalism.

It’s not as though Americans are unaware of this and other related trends, such as the looming climate crisis.*

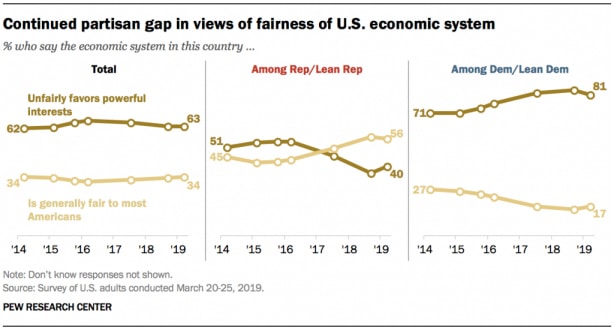

Back in 2014, most Americans (62 percent) said the economic system in the United States unfairly favored powerful interests; only about a third (34 percent) said it is generally fair to most Americans. According to the Pew Research Center, those percentages are almost the same today.**

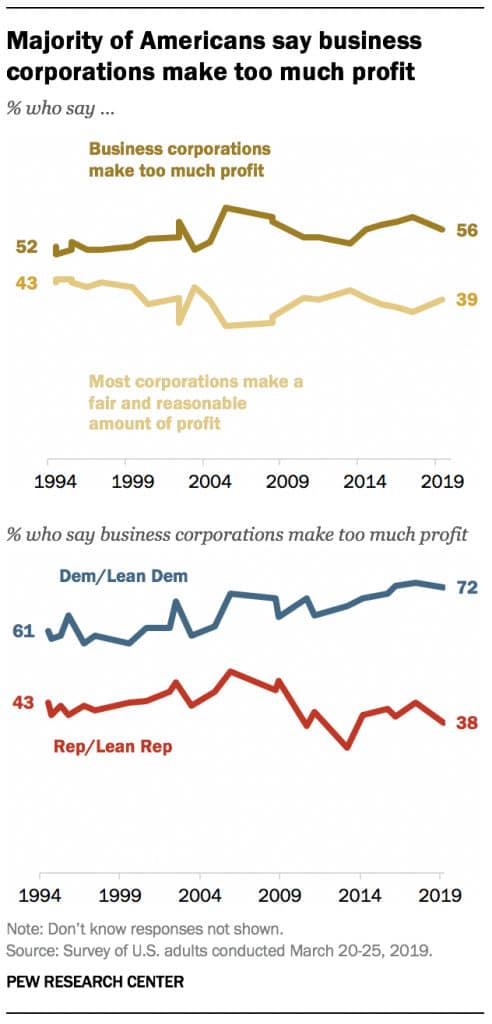

Moreover, the public continues to say that “business corporations make too much profit.” Today, 56 percent of the public says corporations make too much profit; only 39 percent say “most corporation make a fair and reasonable amount of profit.” These views have held largely steady since 1994.

Americans hold similar views about the fairness of the Trump tax cuts (49 percent disapprove versus 36 percent who expressed approval) and the federal tax system (around 60 percent feel that some corporations and some wealthy people don’t pay their fair share).

Clearly, capitalism has lost a great deal of whatever legitimacy it once enjoyed in the minds of Americans.

Time may be running out for capitalism but time is still on our side. Because the same future orientation—the fact that “once the capitalism engine revved up, the future entered our collective imagination”—also includes the possibility that things can in fact be better in the future, even if making things better requires fundamental changes in the way the economy is organized.***

It is that relationship to time created by capitalism, according to which “each generation will rise on the shoulders of the one before,” that both leads to resentment about the unfulfilled promises of the existing economy and sparks the imagination of a radically different way of organizing economic and social life in the future.

*Reeves makes what can only be considered a risible argument on this score: “Blaming capitalism for climate change is like blaming distilleries for drunk driving.” The fact is, global warming is the result of the Capitalocene, in which the activities of corporations have made enormous profits both producing and using fossil fuels—and they haven’t been made to pay for the environmental costs, which they’ve managed to shift to the rest of society.

**The only notable change in the last five years is the fact that Republicans’ and Democrats’ attitudes about the fairness of the economic system have moved in opposite directions: in 2014, there was a 20 percentage-point gap between the shares of Republicans (51 percent) and Democrats (71 percent) who said the economy unfairly favors powerful interests; that gap is now 41 points (40 percent of Republicans versus 81 percent of Democrats). While about eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic leaners say the economic system is unfair, a majority of Republicans and Republican leaners (56 percent) now say the economic system is generally fair to most Americans.

***The problem of time has long eluded mainstream, especially neoclassical, economists. For example, the only way they can envision a general equilibrium of markets is to suspend time, forbidding all trades unless and until there’s a price vector (announced by the mythical “auctioneer”) that brings all (actually, n-1) markets into equilibrium. Once time is introduced and trades take place without supply-demand equilibrium, all bets are off. Then, it’s likely the economy will not be in equilibrium, and may even move further away from equilibrium over time.