Well that didn’t go so well. . .

Still, Elon Musk’s new Cybertruck would appear to be the perfect design for America’s contemporary dystopia. Its bullet-proof stainless steel alloy panels and transparent metal glass are tailor-made to keep its elite occupants safely guarded from attack. And even though the windows obviously need considerable improvement before production begins, and “despite ‘no advertising & no paid endorsement’,” Tesla has already received almost 150 thousand orders for the truck.

Clearly, there’s a lot of surplus available—in cash and loans—to the small group at the top of the U.S. wealth pyramid to purchase such vehicles.

In fact, as we can see from the chart above, auto loans comprise more than 50 percent of the installment loan debt of the top 10 percent of American households (as of 2016, the last year for which data are available). Not so for those in the bottom 50 percent, for whom loans for vehicles make up a little more than a quarter of their installment loans. For them, the largest portion—almost two-thirds—goes to finance higher education.

Consider what this means for the Americans in the bottom 50 percent. According to the latest Survey of Current Finances by the Federal Reserve, 31 percent carry student loans and their average outstanding education debt is $34 thousand. (For those in the bottom 25 percent, it’s even worse: 40 percent of families have student debt, and their average is $43 thousand.) Just student debt is considerably more than the $23,250 average annual pre-tax income of those in the bottom 50 percent.

The only Tesla pickup they’ll be buying is the one with the shattered windows.

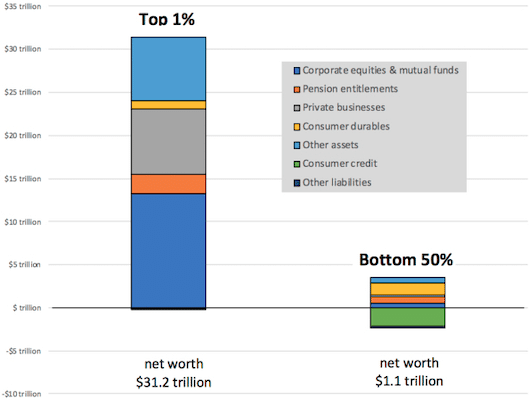

The disparities in the United States are even starker when comparing the assets and liabilities of the bottom 50 percent and the top 1 percent in 2019. As can be seen in the chart above, families in the bottom half own only 6.1 of total assets but are liable for more than one-third of total debts, while the situation of those in the top 1 percent is almost exactly opposite: they have 29 percent of assets but only 4.7 percent of the liabilities.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the net worth (excluding real estate assets and mortgage liabilities) of the bottom 50 percent of Americans is tiny ($1.1 trillion) compared to that of the the top 1 percent (more than $30 trillion).

The question is, why is the net worth of the bottom 50 percent of American households so low? As is obvious from the chart above, they don’t own much in the way of assets and their debt is much greater than that of those in the top 1 percent.

That fundamental inequality in the distribution of wealth in the United States stems from one key factor: American workers’ wages have been stagnant for the past four decades. The average (median) real hourly wage for workers in the private sector is currently $14.99, virtually unchanged (rising only $0.62 or 4 percent) since 1979.*

So, on one hand, American workers simply don’t have the means to acquire many assets, since their wages are just enough for them and their families to get by. And when they do attempt to acquire more, for themselves or their children (in purchasing homes, paying for college, or just keeping with medical bills), they have to go into debt. Therefore, as I argued last week, without wealth of their own, workers and their children are forced to have the freedom to continue to sell their ability to work to employers in order to subsist.

On the other hand, stagnant wages mean that the value workers produce above what they receive in wages goes to their employers, who keep some and distribute the rest to those in the top 1 percent. They’re the ones who accumulate assets, while incurring relatively few liabilities.

That wealth disparity thus ends up playing two roles in the United States: it keeps assets out of the hands of workers (thus forcing them to continue to work to purchase the necessary commodities and to repay their debts) and it concentrates assets at the top of the wealth pyramid (thus permitting the top 1 percent to continue to lay claims on the resulting surplus, whether or not they work).

I have no doubt that taxing some of that wealth would support and expand the kinds of government programs that would help American workers. I’m thinking, for example, of financing universal health care, paying off student debts, providing adequate childcare, and so on. But it wouldn’t increase workers’ wages much less undo the nexus whereby, on a daily basis, most Americans are forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work to a small group of employers.

One of those employers is, in fact, Tesla, which a California judge recently found is in violation of U.S. labor laws.

Imagine, then, an alternative scenario in which Tesla workers, who since 2016 have been battling to form a union (because of high injury rates and low wages), actually owned and ran the Fremont, California factory. The workers, and not Musk and the other members of the board of directors, would then decide what to do with the surplus. The workers themselves would become the board of directors (which might, in turn, decide to hire Musk as a day-to-day executive). The key is that the workers, as a group, would own the assets—not a tiny group of individuals at the top. The worker-owners would thus have acquired a new freedom: to work for themselves, not for someone else. That change in the way Tesla is organized would serve as an example of how to finally undo the obscene wealth inequality that for now decades now has characterized the United States.

It might also eliminate the need for those bulletproof windows.

*I’ll save you the arithmetic: that amounts to a pre-tax annual income of $29.980. That’s the monetary value of the customary standard of living of workers in the United States— which, as we can see, has remained virtually unchanged for the past 40 years.