Read Lexit would have won Part I here.

THAT the neoliberal consensus is in turmoil is agreed upon across the political spectrum–where we find contention is in what exactly it signifies. Trump, Bernie, Brexit, the abortive surge of social democratic parties across Europe met by a more enduring rise in the far right.

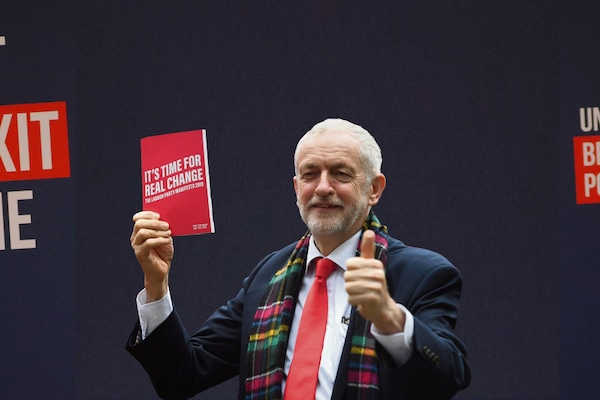

The birth of Corbynism itself, and now, arguably, its death.

Superficially, these upheavals stand in stark left and right opposition, examples of what liberal political scientists call “polarisation.” But the liberal analysis misses what these developments share: their consisting in a rejection of the status quo, of the working class breaking with a politics that demands our blood.

Historically, the “far” left and right have always been coterminous in this sense, standing in dialectical tension: Germany’s Weimar Republic period (1918-1933) was characterised by running street battles between the Social Democratic Party–the largest workers’ movement in European history–and Hitler’s proto-fascist Sturmabteilung. In the early 1920s the country teetered on the edge of full communist revolution; by 1933 the Nazi Party was the largest in the Reichstag.

Recent history illustrates this principle further. Greece’s 2015 elections saw two precedents: the left-wing Syriza gaining a majority, and the openly fascist Golden Dawn surging to become the country’s third largest political force.

French voters in 2017 turned out in huge numbers to support Melenchon’s social democratic vision, and Le Pen’s right nationalism. Months previously Bernie Sanders became a household name, shortly before Donald Trump took the Whitehouse.

Superficially, all this signals a broadly right-wing shift, one often positioned as driven by the poor and uneducated. But a glance at the psephology dispels the phantom of a working class suddenly turned to hard reaction. Le Pen’s 2017 gains only make sense in the context of, and dwarf in comparison to, the Parti Socialiste’s losses.

We see this trend repeated across Europe: where the formerly socialist and social-democratic parties have followed the Blairite model of collusion with neoliberalism, they have collapsed. In the absence of viable left-wing alternatives, far right parties have been the main beneficiaries of this collapse.

Greece, where Syriza won on the promise not only to break with neoliberalism, but ultimately with the EU and its crushing austerity measures, is the notable exception.

That the collapse of the centre, rather than a mythical surge in reaction, best characterises this period is most clearly demonstrated by Donald Trump.

Despite the thousands of column inches and lecture hall hours given to explaining Trump’s rise in terms of the mobilisation of racist, uneducated white voters, the numbers tell a different story: almost one in four white working-class voters who elected Obama in 2012 refused to support Clinton in 2016, many defecting to Trump’s camp, especially those from the post-industrial “rust belt” ignored by Clinton and promised economic transformation by Trump.

While compared to Obama’s 2008 performance Clinton haemorrhaged around 4.4 million votes–mostly black, Hispanic, and/or working class, many of whom simply stopped voting at all.

That voters who elected the first black president in history would switch to the most openly racist president in history on the basis of that racism is absurd. Rather, they rejected Clinton’s promise of more of the same–for some this meant abstention, for others embracing Trump’s offer of change. Just as the British electorate voted for change in 2016.

Millions of us then went on to back the most radical, anti-racist Labour manifesto in a generation, only losing faith as the Labour Party came out in favour of a second referendum, for a continuation of a status quo we had declared as intolerable.

As others have said, Bernie would have won. And for similar reasons, so would Lexit.

To be tediously clear, and head off tedious responses, this does not simply mean working-class Labour voters departed en masse for the Tories, though there is evidence for this to a significant degree: of all leavers who both backed labour in 2017 and turned out in 2019, around 25 per cent defected to the Tories.

But while the Tories gained 800,000 votes from us, Labour lost 2.5 million, with another 800,000 of our 2017 voters staying at home and overall turnout down 1.5 per cent.

Just as Democrat voters abstained rather than cast a vote for the status quo, Labour voters could not be mobilised to vote for remain.

It also does not mean Labour did not lose significant numbers to the Lib Dems, Greens, and SNP, all strongly pro remain parties. The data shows this is true, to the tune of 1.1 million. But these losses are categorically not due to Labour’s lack of remain fanaticism — these people voted for us when we promised to honour the referendum result in 2017.

Rather, polling shows that a lack of faith in Corbyn’s leadership predominated. The only significant difference between now and 2017 was his switch to 2nd referendum equivocation, cast in stark contrast to Boris simple ‘get Brexit done’ messaging. As this essay’s partner piece argues, a boldly articulated left wing case for leave would have changed the terms of the debate, nullifying this threat.

None of this is to deny that racism and reaction were factors in everything above–they were and are, and we must take not one step back in fighting them–but to prompt a question: as the centre continued its collapse, as swathes of the working class abandoned the ship, why did the left raise an EU flag and keep us headed towards the rocks?

In terms of policy direction the answer is clear: Clive Lewis, Michael Chessum, Paul Mason, and other prominent Remainers organised around Another Europe is Possible were allowed to take the helm. The deeper mystery is why they were allowed such influence, why they found such favourable political waters in which to operate, and why we didn’t mutiny against them.

The explanation lies in the middle class’s habitual mistrust of the working class, and contempt for our agency. As the collapse of the political centre outlined above unfolded, much of the media and political establishment began desperately seeking explanations.

Focusing only on the right’s gains allowed them breathe into life the spectre of “populism” to elide their own inadequacy. Some went so far as to disinter the corpse of anti-democratic thought, something done periodically, since Plato, whenever the privileged need to externalise their failings.

Working-class voters were drawn as ignorant, fearful, morally and culturally backwards–a story later regurgitated, with modifications examined below, by much of the middle class, pro-EU left. One imagines a young graduate waking with a shriek, eyes wide and terrified in the pallid glow of the Guardian’s homepage on their Macbook, ragged breaths slowing as visions of Dave the brickie complaining about “immagrunts” fade from their mind.

In keeping with their shared fear and scorn for workers, some more sophisticated “left” figures in this establishment reject the explicit terms of this kind of analysis–when your career is based on being “literally a communist” then open classist bigotry is a bad look–but share most of the same core assumptions, often re-articulating them in more palatable terms and more favourable contexts.

This re-articulation forms not just the ideological core of left Remainism, but all of the middle class’s domination of the left. It’s how they dismiss our interests, demonise our culture, and silence our voices. It takes two interdependent forms.

The first form is simple: attack the working class on the same terms as the liberal establishment, while avoiding open expressions of class hostility, and masking it as a left-wing critique.

The second form is more complex and often relies on academic sophistry: redefine the working class, or at least the legitimate working class, to exclude those who don’t fit an idealised, cosmopolitan mould.

This strategy obtains in every “People’s Vote” rally, in every sneering hipster’s tweeted quip about “gammons.” But it was perhaps most prominently deployed in this instance by two luminaries of the “left” commentariat: Novara Media’s Ash Sarkar and the Guardian’s Owen Jones.

Sarkar filmed a post-referendum vox pop which saw her wandering the streets of Barking, a Leave borough where nearly 30 per cent of children live in poverty, asking leading questions to mostly white and clearly working-class voters, all with thick East London accents, before switching to sharply dressed, well spoken people of colour for contrast.

Despite clearly looking for examples of entrenched racism, and presumably doing many more interviews than were shown, the worst she can get out of anyone is complaints about immigration.

Rather than expressing explicit racial or cultural bigotry, every single one of these is couched in economic terms–lack of jobs, strain on the NHS and housing, one elderly couple even cite a seven-week disability benefit sanction–and most are accompanied by expressions of sympathy and tolerance.

One lad of 17 complains about immigrants “taking jobs” before immediately qualifying it with “I know it’s not all foreigners, some of them are doctors and save our lives.” He then stutters, eyes on the floor, though a confused argument about immigrants both taking jobs and being on benefits.

Later she explains these responses with no reference to class, or to the economic concerns the interviewees openly spoke of. Instead complaining of their “cognitive dissonance” and racist desire for “British sovereignty”–a desire none of them expressed. She goes on to cite “whiteness” to explain their “entitlement” and “aggrievement.”

As if the working class isn’t entitled to decent jobs and public services, to care when we’re sick. As if the slowly crushing horror of a poverty she’s never known isn’t cause to be aggrieved. As if immigration doesn’t function as a cipher for these economic concerns, as any communist will tell you. As if these attitudes can’t be quickly dispelled with basic left-wing arguments, as anyone who’s bothered to try would know.

To be clear, the attitudes these people expressed are racist. They are dangerous and must be fought. But it does not follow that the people who hold them are irredeemably racist, or dangerous–to dismiss them as such is to follow the fourth rule of the vampire castle, and to make social change based on mass working-class participation impossible.

The job of us gifted a political education is to arm these people with the intellectual tools to better understand who their enemies are.

Another explicit and egregious example of this came in the form of attacks on Eddie Dempsey: an RMT trade unionist respected for successfully organising migrant workers others wrote off as not worth the time, as well as spending most of his adult life physically opposing fascism–often literally in toe-to-toe fights.

At a Lexit rally in March 2019, Dempsey adduced the middle class, liberal left’s abandonment of vast swathes of the working class as a reason for many workers shifting right (much as we do in this essay), saying:

Whatever you think of people that turn up for those Tommy Robinson demos or any other march like that–the one thing that unites those people, whatever other bigotry is going on, is their hatred of the liberal left. And they are right to hate them.

He went on to say that Labour’s electoral calculations had them targeting the votes of two sections of the working class: the relatively well-off and middle-class assimilationist, and the non-white, while ignoring those who don’t fit either of those categories.

Given Dempsey’s history of trade unionism and anti-racism, one might expect these words to be read charitably, in context, and his criticism of the liberal left taken seriously.

Instead, prompted months later by Clive Lewis MP, Sarkar and Owen Jones publicly announced their refusal to share a stage with Dempsey at a People’s Assembly event.

To spell out the sleight of hand here, Dempsey’s argument was negative:

the left should not abandon X part of the working class (namely those mostly white, mostly post-industrial, mostly Leave voting workers open to the far right’s seduction). While Jones and Sarkar responded as if he’d made the positive argument: the left should abandon Y part of the working class (namely ethnic minorities).

That the latter does not follow from the former shouldn’t need pointing out.

This bait and switch manoeuvre is central to Remainism. Any attempt to point out that, outside of the big cities, the working class is often over 90 per cent white, often concentrated in post-industrial towns, and mostly voted Leave can be met with scorn, accusations of racism, and derisive comments about the trope of a “white working class” which excludes ethnic minorities.

Again, more broadly this strategy serves the dominance of the middle class, university educated left and their agenda. Joan Hardwicke recently pointed out that the time and energy the left spent talking about and attempting to organise sex workers–driven largely by a burgeoning academic interest in them–was not justified by by the results: just 150 workers recruited across two unions in 18 months, and not one collective grievance voiced, let alone a strike.

She argued that this energy would be better focused on migrant cleaners, Deliveroo riders, and the like–workers whose unprecedented recent victories point the way towards building real working-class power. Predictably, she was broadly denounced, accused of everything from Stalinism to a secret desire to kill sex workers.

The grand irony of course, is that in deploying moralism and shame tactics against those who point out uncomfortable truths, it’s the middle class which constructs a distorted image of the working class.

By universalising the experiences of the upwardly mobile, the cosmopolitan, and the urban–of Sarkar, Jones, and their mates–by making their cultural values and political interests the only ones we’re allowed to discuss, they make it impossible to engage with the vast majority of workers.

As the exit poll came out on Thursday, we saw where that gets us.

It’s tempting to psychologise here. It’s in the commentariat’s career interests to maintain their lofty positions by attacking the working class–can’t risk that spot on Sky News about working-class politics going to an actual worker–and in the broader middle class’s interests to have their cultural values dominate.

But often we’re too quick to cite cynicism in our opponents. Was there an element of deliberate careerism to Sarkar and Jones’s sectarianism? Probably. Is there deliberate bigotry at play when the middle class silence us? Perhaps. They also probably think they’re doing the right thing.

Whatever we think of our opponents’ motivations, what we know for sure is that they’ve led us to defeat. To five more years of Tory rule. To a Brexit on the terms of Boris and Trump. To continuing austerity and racist policy. And probably to the end of what’s left of the NHS.

And we know they’ve shown no signs of learning.

George West is a writer living in London. He blogs at From Every Crime.