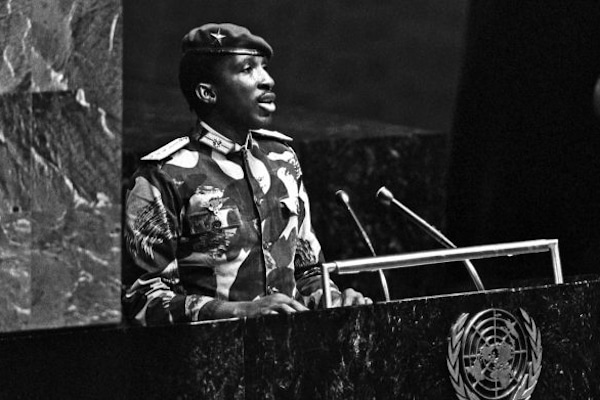

President Thomas Isidore Noel Sankara would have turned 70 on the 21st of December 2019. At the tender age of 37, however, he was felled by bullets from soldiers loyal to his best friend, Blaise Campaore. Thomas Sankara’s passion was Africa’s advancement; his experimental field was Burkina Faso. What President Sankara wanted to see in Africa, he strategized, mobilized and implemented in Burkina Faso. He would then present his successes to African leaders, while encouraging them to surpass his achievements. Thomas Sankara’s achievement are too numerous to be summarized in an essay or even be elucidated in any book, but a few key points will be here noted.

Perhaps, the first in Thomas Sankara’s achievement is his refusal to borrow a dime from the IMF or any other foreign government or agency, mobilizing instead his fellow citizens to invest in community development and to consume only what the land of Burkina Faso yielded. Likewise, President Sankara, at the risk of being a target of the malignancy of Western governments, strongly encouraged other African leaders to shun external aid and borrowing. Thomas Sankara implored African leaders to rethink governance by reorganizing governmental systems and expressing those systems along a different line from the West in order to reduce costs and simplify governance.

A Pan-Africanist who was deeply committed to the cause of African people, it bothered President Sankara that African leaders were not seriously investing in the progress and unity of the continent, but were excited about uniting and aligning with the West. At a 29 July 1987 meeting of African leaders in Addis Ababa, he decried the poor attendance often recorded at meetings where Africa’s advancement is discussed; “Mister President,” he asked the [O]AU chairman, “how many heads of state are ready to head off to Paris, London, or Washington when they are called to a meeting there, but cannot come to a meeting here in Addis-Ababa, in Africa?”

Like Patrice Lumumba, Sankara incurred the wrath of the French President, Francois Mitterand when Mitterand visited Ouagadougou in 1986. Citing the spirit of the 1789 French Revolution, President Sankara reprimanded France for its oppressive policies in Africa and for the disrespectful treatment of African immigrants in France. Mitterand was livid with rage. He was used to African leaders groveling and shriveling under the mighty-hand of France. The French President would toss his prepared speech aside and take on Sankara, concluding with the thinly veiled threat, “This is a somewhat troublesome man, President Sankara!” Many would say that Sankara’s days were numbered after that fateful visit.

Prior to the French President’s visit, Thomas Sankara, a man of deep philosophical convictions, had in 1984 dumped the colonially contrived and imposed name of Upper Volta to call the nation what they wanted to be known as, Burkina Faso, “Land of Incorruptible People.” That renaming exercise was paired with an asset declaration exercise where President Sankara made known his properties, consisting of one working and one broken down refrigerators, three guitars, four regular motorcycles and one car. Thomas Sankara capped his salary at $462 and forbade both the hanging of his portrait at public places and any form of reverence attached to his person or presence. Burkina Faso is about Burkinabes and there are 7 million of them. This seemed to be his guiding principle.

Thomas Sankara believed and invested in the education of Burkinabes. Literacy rate was at 13% when he became the president in 1983, and by the time of his assassination in 1987, it stood at 73%. Under his administration, numerous schools were built in Burkina Faso through community mobilization, teachers were trained and women were strongly encouraged to pursue education and career.

Burkina Faso’s agricultural fortunes experienced a turnaround during Thomas Sankara’s administration. First, the consumption of imported goods was strongly discouraged and Burkinabes once more reclaimed their taste buds from France. Thomas Sankara redistributed idle-lying lands from wealthy landowners to peasants who were eager to cultivate them. In three years, wheat cultivation jumped from 1700 kg per hectare to 3800 kg per hectare. His administration further embarked on an intensive irrigation and fertilization exercise leading to an outstanding success across other crops including cotton. Burkina Faso soon become self-sufficient in food production, while cotton was used to make clothes, after having banned importation of clothing and textiles.

Convinced that the health of Burkinabes was paramount in any conversation regarding national advancement, President Sankara flagged off a national immunization program that–within weeks–saw the vaccination of over 2.5 million children against meningitis, yellow fever and measles. Access to healthcare was a basic human right of every Burkinabe and President Sankara mobilized communities across the nation to build medical dispensaries, thereby ensuring the proximity of primary healthcare to citizens in the most remote areas.

Infrastructural challenges were tackled headlong by President Sankara, mostly through the mobilization of citizens, both rich and poor, as construction workers in the building of access roads and other structures across the country. Within a short period of time, all regions in Burkina Faso became connected by a vast network of roads and rails. In addition, over 700 km of rail was laid by citizens to facilitate the extraction of manganese. In order to move Burkinabes away from slums to dignified houses, brick factories were built, which utilized raw materials from Burkina Faso. For the sake of emphasis, all these were achieved without recourse to borrowing or external financial assistance in a nation dubbed one of the poorest in Africa before Thomas Sankara became the President.

A man of integrity and transparence, Thomas Sankara expected nothing less from everyone in leadership position in Burkina Faso. Thomas Sankara refused to use air conditioning system as president of the country, since according to him, that will be living a lie as majority of Burkinabes could not afford such. Upon assumption of power, Thomas Sankara sold off the government fleet of Mercedes cars and commissioned the use of the cheapest brands of car available in Burkina Faso, the Renault 5. Salaries of public servants, including the president’s, were drastically reduced, while the use of chauffeurs and first-class airline tickets were outlawed.

Ever before women advancement became a buzzword globally, President Thomas Sankara led the way in advocating for the equal treatment of women. His cabinet was heavy with female appointees while numerous governmental positions were occupied by women. Female genital mutilation, polygamy, underage and forced marriages were outlawed while women were encouraged to join the military and to continue with their education even during pregnancy.

Thomas Sankara was passionate about the environment and its conservation. He encouraged citizens to cultivate forest nurseries and over 7,000 village nurseries were created and sustained, through which, over 10 million trees were cultivated in order to push back the encroachment of the Sahel desert.

President Sankara pursued peace with his adversaries. On the morning he was gunned down, he was armed with a speech he had worked on all night, aimed at reconciling opposing factions in Burkina Faso and addressing the grievances of certain sections of the labor force. He did not live to present that speech.

In the short time he had, Burkinabes advanced as a nation and as a people. Outside of the already enumerated physical signs of progress, the social psychological impact on Burkinabes, of being truly and completely independence for the first time since the late 19th-century colonial incursion, was tremendous. Ironically, it was that same independence from France, termed “a deteriorating relationship” with the former colonial powers that Captain Blaise Campaore cited as one of the major reasons why he instigated the coup against Sankara.

Africa has produced much greatness; let it never be said that the continent is lacking in greatness. If truth be told, Africa’s great people of character and principle have often been silenced by forces of greed, exploitation and selfishness. Africa must then learn to build strong and enduring systems for the protection of virtue, the promotion of character and the vilification of vice. Africa would have been better than what it is today, if Thomas Noel Isidore Sankara were alive as an elder statesman to celebrate his 70th birthday anniversary. Yet, in death, he continues to serve as an inspiration to many Africans on what we can become as individuals and as a continent if we choose selflessness, commitment and passion for the continent and her people as the driving force behind our actions.