Britain’s exit from the imperialist bloc known as the European Union (EU) is now irreversible. The crushing electoral defeat of the Labour Party has dismayed many workers and youth who had placed their hopes in Jeremy Corbyn, its left-wing leader. This article assesses these historic events, neither of which can be understood in isolation from the other.

Brexit

The United Kingdom is a declining imperial power comprising Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Right-wing politicians look everywhere except in the mirror for the causes of this decline, and hark to a time when Britain stood alone against the Nazi hordes and single-handedly rescued world civilisation, with some belated help from the USA. But this cherished national myth is a fantasy. The Nazi army’s back was broken on the eastern front, by the Soviet Union—not by Britain, which was busy fighting a colonial war in north Africa while the Soviet army and people were doing the heavy lifting. Britain’s losses at El Alamein, the biggest battle fought by the British Army before the Normandy landing in June 1944, were less than 2,000, while half a million Soviets died in the Battle of Stalingrad. Racism, hypocrisy and imperial hubris—core British values, in which all its political parties and institutions are steeped—explain the otherwise inexplicable madness known as Brexit.

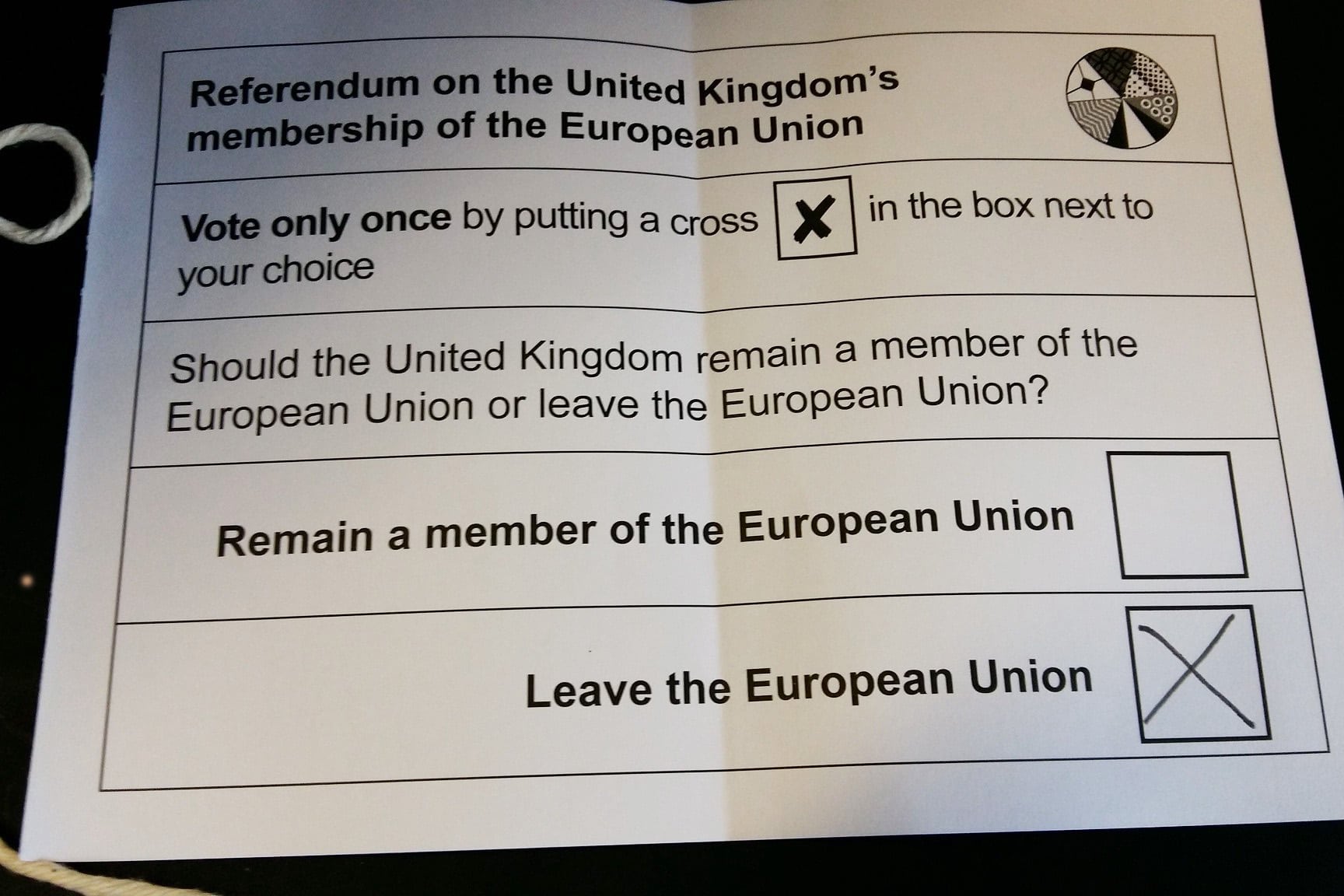

Imperial hubris notwithstanding, Britain’s capitalist rulers are confronted with a strategic dilemma: whether to ally with France and Germany in the EU, or to align with the USA—two directions equally inimical to the interests of workers and all oppressed people. Divisions within the ruling Conservative Party over this led in 2016 to a referendum in which voters decided, by a narrow margin, to leave the EU. In a previous article I explained why this outcome was determined by workers’ hostility to the EU—two thirds of workers voted to leave; and why the single-most important factor inducing them to do so was opposition to immigration—freedom of movement across the EU’s internal borders is one of the pillars of its free trade area, yet many workers suffering increasing insecurity and declining living standards blame these ills on increased competition from migrant workers and demand state protection against them.

During the three years of political turmoil following the 2016 referendum, the biggest obstacle to an orderly exit turned out to be the century-old partition of Ireland into the Irish Republic in the south and the British-occupied enclave in the north (see here for more on this). So long as both Britain and Ireland remain in the EU, people and goods can cross the border between the two parts of Ireland without even noticing, but the UK’s exit from the EU trade area would require the imposition of a hard border, dealing a severe blow to Ireland’s economy and risking reignition of armed struggle against the British occupation.

Former Prime Minister Theresa May negotiated an exit deal that evaded the border problem—by keeping both Britain and Northern Ireland inside the EU’s free trade zone until the conclusion of negotiations, yet to begin, on a permanent trade relationship; and a guarantee that, whatever its outcome, Northern Ireland would remain within the EU’s free trade zone and subject to its rules. May tried and failed three times to get this through Parliament, whereupon she resigned and Conservative party members, mostly rich white men over the age of 60, chose Boris Johnson as their leader.

Johnson duly reopened negotiations on the terms of the UK’s exit. As before, the EU insisted on a guarantee of no hard border between the two parts of Ireland. To the surprise of many (including this author), Johnson capitulated, agreeing a revised deal whose only substantial difference with the previous one is provision for a de facto permanent border between Britain and the whole of Ireland, while maintaining the pretence of UK constitutional integrity. In face of howls of betrayal from pro-imperialist Unionist politicians in Northern Ireland, Johnson flatly denied what was written in black and white in the deal he had negotiated, and rammed it through Parliament.

The December 2019 general election—fake democracy in action

As Johnson’s denials indicate, he has no intention of respecting the terms of the exit deal. His concession on the border question was entirely tactical—to get a deal through Parliament by any means and to then call a general election, in which the Conservative Party would campaign around a simple slogan: ‘Get Brexit Done’.

Its main opponent, the Labour Party led by Jeremy Corbyn, was hopelessly divided on the EU as on so much else. It tried and failed to shift the national debate away from Brexit and onto the government’s policy of austerity, which has resulted in a major deterioration of publicly funded health and education services. Concerning Brexit, Corbyn promised to rapidly conclude a new trade agreement with the EU that would preserve the UK’s current trade arrangement and so avoid any loss of jobs. He glossed over the fact that this would inevitably require UK submission to EU regulations, acceptance of freedom of movement and continued contributions to the EU budget—all that would change would be loss of UK’s ability to shape EU policy. Corbyn promised to put this Brexit-in-name-only deal to a second referendum, with voters invited to choose between this or cancellation of Brexit altogether—and that he would remain neutral!

Corbyn and the Labour Party paid a heavy price for their incoherent stance on the central issue of Brexit, but, as we shall see, this was far from the only reason why they were trounced at the polls. In the event, Labour received 32.2% of the vote versus 43.6% for the Conservative Party. Taking turnout (67.3%) and those not registered to vote (17%) into account, the Conservative’s “landslide victory” was achieved with the votes of 24% of the electorate, while just 18% voted for Labour. More workers voted Conservative than Labour—among unskilled workers, the margin was 43% to 37%, while skilled and semi-skilled workers voted for the Conservative Party by an even bigger margin. Gender divisions were also much in evidence—men voted by 48% to 29% in favour of the Conservatives, while the margin amongst female voters was much smaller, at 42% to 36%. The generation gap was particularly striking—just 19% of the 18-24 age group voted for Conservatives versus 57% for Labour, in diametric contrast to the over-65s, 62% of whom gave their vote to the Conservatives compared to just 18% for the Labour Party.

How many of these voters actually believed in what they voted for, rather than lumping for the lesser of two evils, is anyone’s guess. Opinion polls in the UK show that politicians and journalists are, by a wide margin, the least-trusted of all professions. As for journalists, most of the print media is owned by ultra-reactionary billionaires, while the broadcast media is firmly in the grip of middle class liberal meritocrats who exude contempt for working people. This isn’t democracy, it is a travesty of democracy!

The crushing of the Labour left

Labour’s absurd non-policy on Brexit was not the only reason why its vote collapsed. Two others, in particular, must be highlighted.

First, while Labour’s economic policies were popular among workers and youth, few believed in its ability to deliver them. Labour promised to significantly increase taxes on the rich and on corporate profits; to nationalise rail, water, mail and electricity companies; to force big firms to transfer 10 per cent of their shares to employees; to cap rents and increase tenants’ rights; to launch a £400bn (£1 = $1.3) National Transformation Fund to finance transition to a zero-carbon economy and “upgrade almost all of the UK’s 27 million homes to the highest energy-efficiency standards”; to establish a £150bn Social Transformation Fund to repair or replace dilapidated schools and hospitals; to borrow a further £250bn to fund a National Investment Bank; to sharply increase the minimum wage, state pensions and other social transfers; to provide 30 hours of free childcare to all children aged two to four; to cancel tuition fees and provide maintenance grants for University students; and much else.

The desirability of this shopping list is not in question, its credibility is. Many sensed, with good reason, that attempts to carry out these promises would trigger capital flight and a collapse of the pound, plunging the UK’s already-fragile economy into a deep crisis, resulting in an intensification of austerity, not an end to it.

The Bank of England’s official lending rate is 0.75%, and is negative once inflation is taken into account. This is lower than it has been in the Bank’s four centuries of existence. Ultra-low interest rates in the UK and all other imperialist countries indicate the extreme depth of capitalism’s systemic crisis—”a supernova waiting to explode,” in the words of foremost bond trader Bill Gross (see here for a brief explanation). Yet, to the Labour left, ultra-low interest rates are not a flashing red light, but a green light inviting them to borrow vast amounts of money from those who have it, i.e. the super-rich. Yet history, e.g. Greece under Syriza, teaches that, when asked to lend money to a government they do not trust, capitalists are certain to demand a hefty risk premium, wrecking public finances and destroying reformist dreams.

If Corbyn and his supporters harboured any doubts that Britain’s capitalists would peacefully acquiesce to this programme of radical reforms, they didn’t let on. But you can’t lead people into a battle by pretending there won’t be one. Demoralised by decades of defeats, demobilised by servile, silver-tongued trade union leaders, and disoriented by an incessant, uncontested barrage of imperialist propaganda from both the liberal left and the white nationalist right, most workers showed by their votes that they are not itching to fight their rulers, they just yearn to be patronised by them. Since the 19th century Britain’s plutocratic rulers have sought to bind workers into an imperialist alliance against the rest of the world. Following World War II, for example, rising national liberation struggles in Britain’s colonies and neo-colonies—not just the social reform movement at home—convinced them to concede workers’ demand for free healthcare and education. Their aim was to pacify the working class and to secure the active support of its trade union and political leaders for wars against insubordinate governments and insurgent peoples around the world. This imperialist social contract is the very essence of British social democracy, in both its left and right variants. Now, compelled by the depth of the capitalist crisis, Britain’s rulers are moving to dismantle this social contract, sending social democracy into a tailspin.

The second factor in Corbyn’s defeat was his attempts to reconcile diametrically opposed views within the Labour Party on freedom of movement and a wide range of other controversial issues, resulting, in practice, to abandonment of his vaunted principles and capitulation to the right wing.

Jeremy Corbyn, who pointedly describes himself as a democratic socialist rather than a social democrat, had spent his entire political life as a dissident on the left wing of the Labour Party, where he earned a reputation as a consistent opponent of imperialism’s wars, including those waged by Labour governments, and as a defender of the Palestinians and others battling racism and imperialism across the world. He was swept into the leadership of the Labour Party in 2015 by an influx of workers and youth who had been radicalised by Britain’s participation in the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 and by the global financial crisis which erupted in 2008 and was epicentred in London and New York—both of these events occurred under Labour governments led by openly pro-imperialist right-wing social democrats.

Concerned that Corbyn could not be trusted to defend Britain’s extensive imperialist interests in the Middle East and elsewhere, a vast campaign was launched—involving right-wing politicians within the Labour Party, virtually the entire print and broadcast media, the Israeli embassy and key figures within the British establishment—to brand him and the Labour left as anti-Semitic. Jew-hatred is indeed a deadly threat, and history teaches that it flourishes in a time of systemic capitalist crisis, as now, when demagogues of both left and right deflect the anger of workers and the dispossessed against Jewish capitalists rather than against the capitalist class as a whole. Anti-Semitism is also fostered by bourgeois nationalists in the Middle East, who resent the imperialists’ indulgence of Israel and wish to be treated equally. It is far from the case, therefore, that the fascist right wing has a monopoly over anti-Semitism. On the contrary, its poison has infected the left and the world movement in solidarity with the brutally oppressed Palestinian people.

Detailed analysis of this is beyond the scope of this article. What must be noted, however, is the utter incapacity of Corbyn and the Labour left to defend itself. To do so, it would have had to educate itself and the broader movement about the nature of anti-Semitism and why it becomes virulent during times of crisis. To expose the cynicism of its accusers it should have gone on the offensive, by exposing the vile history of British imperialism in the Middle East and, critically, Britain’s complicity in the Holocaust—Britain slammed its door in the face of Jewish refugees during the 1930s; later, while World War II raged, Winston Churchill suppressed news of the genocide because he didn’t want to be distracted from Britain’s colonial wars in North Africa and Burma. But Corbyn and the Labour left did none of these things. From the moment he was elected leader of the Labour Party Corbyn stopped talking about Palestine. Similarly, he maintained a stony silence in the face of vociferous criticism of his record of speaking out against the British Army’s violation of human rights and its collusion with paramilitary death squads in Northern Ireland and his support for anti-imperialist governments in Latin America.

So what’s next?

Britain’s Brexit crisis is now in temporary remission. Negotiations with the EU over a permanent trade relationship, and with the USA over a new trade deal, will be even more excruciating than those leading to Britain’s exit.

Britain’s economic stagnation will inevitably be aggravated by disruption to trade with the EU, the destination for over 40% of the U.K.’s exports. Economic nationalism and nostalgia for empire will mutate into ever-more virulent variants.

Brexit has already dealt a severe blow to Britain’s domination of Northern Ireland, reunification is now firmly back on the agenda, and is also driving the divergence of Scotland from England; demands for a second referendum on Scottish independence will grow louder. The United Kingdom is disintegrating—a cause for celebration, not for mourning!

Corbyn’s attempt to turn the Labour Party into a socialist party has ended in failure. Social democracy in Britain, as in France, Germany, Italy, Greece and other imperialist democracies, is dead and attempts to resuscitate it are futile. Its demise should be celebrated, not mourned. The socialist movement must be internationalist, anti-imperialist and revolutionary, or else it is not socialist and it cannot advance.