On April 30 the U.S. Department of Justice announced that it was charging Juan Carlos Bonilla Valladares, a former head of the Honduran National Police, with “conspiring to import cocaine into the United States.” According to Manhattan U.S. Attorney Geoffrey S. Berman, the ex-police chief carried out some of his crimes “on behalf of convicted former Honduran congressman Tony Hernández and his brother,” Honduran president Juan Carlos Hernández.

This is the third time in less than a year that the U.S. government has linked the Honduran chief executive to drug traffickers. President Hernández denies any association with narcotics smuggling.

On the same day that the Justice Department announced charges implicating Hernández, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security released the text of an asylum agreement it had finalized with Hernández’s government. The accord, in the works since last fall, is a de facto safe third country arrangement under which Honduras agrees to accept people other than Honduran citizens or residents who try to seek asylum in the United States. This is the latest step in the Trump administration’s long-term drive to end the U.S. asylum system.

President Trump expressed his gratitude for Hernández’s cooperation a few days earlier: “We work closely together on the Southern Border,” Trump tweeted on April 24. “Will be helping [Hernández] with his request for Ventilators and Testing.”

“War on Drugs”

To many people it might seem astonishing that the U.S. government can repeatedly claim to be waging a “war on drugs” at the same time that it makes deals with a man it accuses of collaborating with drug traffickers.

It’s not as if the Trump administration isn’t willing to file drug trafficking charges against Latin American presidents. On March 26, U.S. attorney general William Barr did just that, but not against Hernández. The target was leftist Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro. Barr accused Maduro of narco-terrorism, drug-trafficking, and corruption; the attack on the Venezuelan ruler included the State Department’s offer of a $15 million reward for information leading to his arrest.

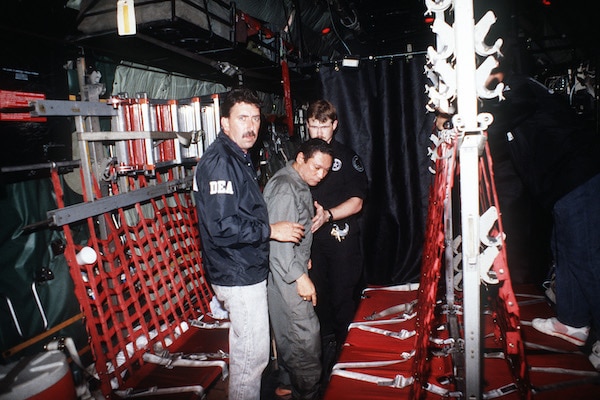

There’s also a military threat. On April 1 Trump announced that he was deploying what amounts to a small fleet to the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific in a move clearly aimed at Venezuela. The operation, one of the largest in the hemisphere since the 1989 invasion of Panama, comes at a time when the U.S. Navy already has to deal with two ships experiencing major outbreaks of COVID-19 infections.

Trump claimed he was reacting to the “growing threat that cartels, criminals, terrorists, and other malign actors will try to exploit the [COVID-19] situation for their own gain,” but the pretext doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Venezuela has a relatively small role in cocaine smuggling, which is centered in Mexico and Central America, according to the Washington Office on the Americas (WOLA). The liberal think tank also notes that such a massive military operation had to have been planned long before the administration started to take the pandemic seriously.

(In a possibly related development, two former U.S. Special Operations soldiers were arrested and a number of Venezuelan defectors were reportedly killed early in the week of May 3 in what appeared to be an attempt by a small armed group to invade Venezuela. On May 6 U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo denied any “direct involvement” by the United States.)

A New “Dark Alliance”

There doesn’t seem to be much public outrage about the blatant hypocrisy of Trump using the Navy to threaten Maduro while bonding with Hernández on Twitter.

A few reporters have noted the contradictions in U.S. policy—Claudia Mendoza and Mary Beth Sheridan in the Washington Post, for example. In general, though, the lack of editorials and opinion pieces on the subject is striking, as is the silence of most Democratic politicians. But this isn’t surprising. After all, U.S. foreign policy is essentially bipartisan. The corporate media and the Democrats were generally supportive of the 2009 military coup that resulted in the current lock on power by Hernández’s rightwing National Party, and the Obama administration continued to aid the Honduran government after Hernández became president in 2014, despite his administration’s record of human rights abuses.

If anyone is going to step up on this issue, it will have to be the U.S. left. But this isn’t just a responsibility—it’s also an opportunity to reach out to broad sectors of the working class, especially white workers susceptible to Trump’s propaganda.

In 1996 the San Jose-based Mercury News ran a series of investigative articles by reporter Gary Webb highlighting the role of the U.S.-backed Nicaraguan contras in cocaine trafficking during the 1980s. The contras’ trafficking had already been revealed by two Associated Press reporters and documented by a Senate investigation, but Webb’s “Dark Alliance: The Story Behind the Crack Explosion” brought the scandal to a broader audience. The exposé immediately provoked an outcry, notably in African-American communities that had suffered the most from the spread of crack use during the period.

The U.S. political class and corporate media quickly mobilized to shut down the discussion and to ruin Webb’s career—he eventually committed suicide. But that happened at a time when the U.S. left was much weaker than it is now and public trust in the U.S. government was considerably higher.

Since the outbreak of the opioid crisis, white working-class communities have been ravaged by drug use in much the same way as African-American communities were in the 1980s. What would be the effect on these white communities—many of which turned out for Trump in 2016—if progressive activists and media mounted an updated “Dark Alliance,” a campaign to expose the link between Trump’s anti-asylum agenda and his backing for a corrupt ruler that the U.S. government itself accuses of aiding narco-trafficking?