OK, I’m done with all these trite catchphrases about all of us being in this mess together.

We’re not. We never have been. And we won’t all be in this together moving forward.

Earlier this month, I argued that, while there may be a utopian moment in the common refrain, the obscene inequalities that are produced by the prevailing economic and social institutions in the United States empty that phrase of any real meaning. I referred, in particular, to the fundamental difference between the conditions of workers who have been forced into unemployment or are commuting to and working in dangerous jobs and those of billionaires who have gotten wealthier and corporations that have been bailed out during the pandemic crisis. The disparity could not be starker.

Yes, I was pretty angry, as I’m sure millions of other Americans were.

And then I read the New York Times article about the people who left New York City as the coronavirus pandemic hit, and those who didn’t. That was it!

Sure, we’d all heard or read stories about the wealthy taking to their yachts and private jets, procuring their own ventilators, availing themselves of concierge testing, and much, much more.

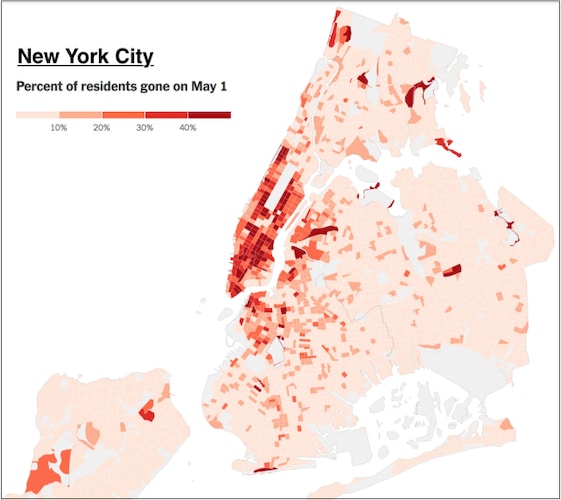

But then the Times revealed that, between 1 March and 1 May, the wealthy managed to empty out of New York City en masse—leaving everyone else behind.

In the city’s very wealthiest blocks, in neighborhoods like the Upper East Side, the West Village, SoHo and Brooklyn Heights, residential population decreased by 40 percent or more, while the rest of the city saw comparably modest changes.

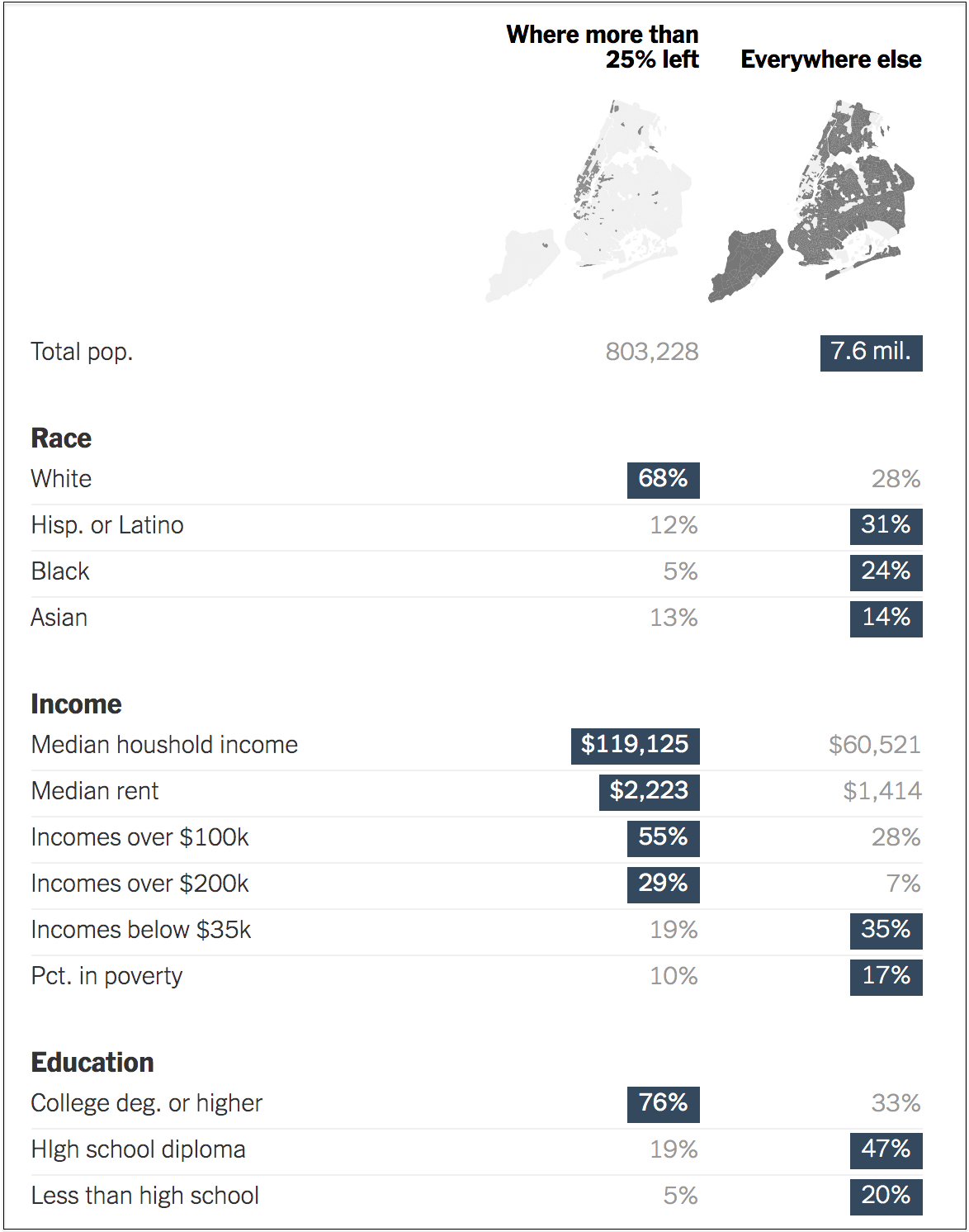

The neighborhoods driving the exodus from the city do not in any way, shape, or form resemble New York City as a whole. The people who left are mostly white in a city that’s mostly not. They are more than twice as likely to have a college degree. These places they left have higher rents and lower poverty rates. And the incomes of residents there are considerably higher: more than half of these neighborhoods’ residents have household incomes of more than $100 thousand, nearly one in three taking in more than $200 thousand, compared to $60 thousand in the other areas, with more one-third earning less than $35 thousand.

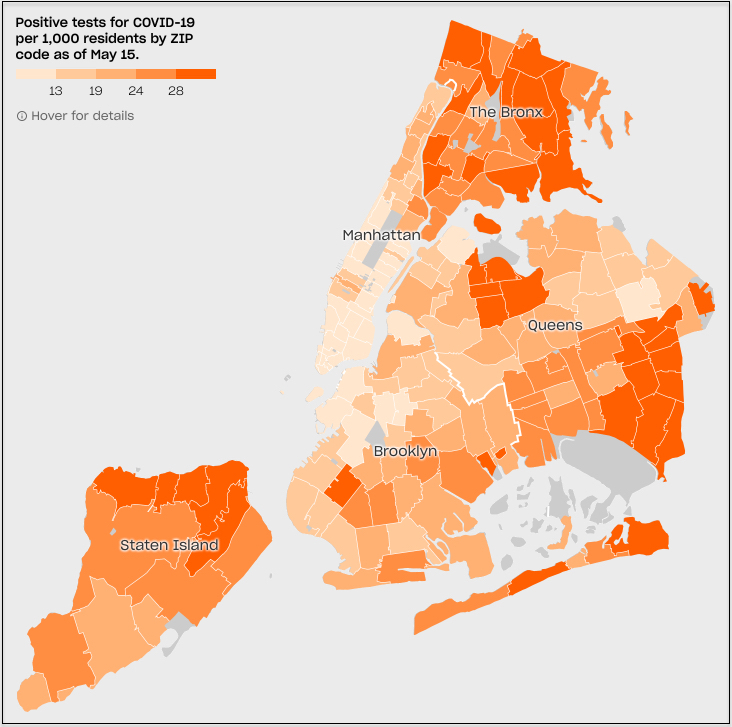

I’ve already shown how New York City represented a tale of two cities by comparing the map of where frontline workers live within New York with the map of the confirmed cases of coronavirus in the city. The two were virtually identical.

Now compare the map at the top of the post with the latest map of positive tests for COVID-19. Once again, the maps are almost identical: areas that have the highest rates are also the ones where residents could not escape and go elsewhere. Take, for example, Baychester. It’s a neighborhood geographically located in the northeast part of the Bronx, adjacent to Coop City. More than 95 percent of its residents have remained in place and there are 38 cases of confirmed cases of coronavirus per 1000 population, one of the highest rates in the city. And Gramercy Park, in Manhattan? There are only 8.2 cases per thousand and more than 40 percent have managed to leave the area.

Even if they’d stayed in their upscale neighborhoods—in their expansive apartments and penthouses, with or without their maids, cooks, and nannies—they would have been safer than most other residents of the city. But they didn’t bother. Instead, they abandoned their fellow New Yorkers and headed out of town.

There’s nothing about the pandemic crisis that has treated people equally. On the contrary! The infection rates as well as the consequences of the economic response merely reflect the already obscene levels of inequality that preceded the arrival and spread of the pandemic in the United States.

And, if anything, all signs point to a worsening of those inequalities over the course of the pandemic crisis.

I know, that’s hard to imagine. But if this unequal emptying out—of New York City literally, and of the country metaphorically—doesn’t make people mad as hell, I don’t know what will.