While everyone was busy looking at the COVID-19 numbers across the world, other “stuff was happening” in international trade: the U.S.-China trade war, which started as far back July 2018, just got significantly worse. This on-again off-again war has been a feature of the Donald Trump presidency, with the man at the helm since January 2017 vowing to prevent the U.S. from being “exploited” by other countries, notably China, that had benefited from the U.S. market by running bilateral trade surpluses.

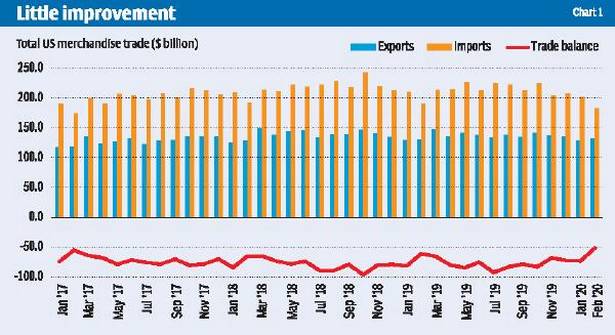

Trump focussed on the U.S. aggregate surplus as well as certain bilateral surpluses, missing the basic point that aggregate trade and current account surpluses in an economy are the result of internal macroeconomic imbalances (between aggregate domestic savings and investment) that are unlikely to be affected by trade measures alone. Protectionist measures against Chinese imports only lead to imports from alternative sources being substituted. Indeed, as Chart 1 shows, the period of Trump’s presidency has seen very little “improvement” in the trade balance. The very recent reductions in the U.S.’ overall trade deficit reflect changes in global trade, specifically affected by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Trade tensions

China was identified as the biggest villain of the piece, and not just because it had the largest trade surplus with the U.S. of all trade partners. The trade war officially started on July 6, 2018, when the U.S. imposed a 25 per cent tariff on Chinese imports worth $34 billion. This was just the first in a series of increases in tariffs over the subsequent year, and China also retaliated with tariffs on some U.S. goods (albeit on lower values of imports).

Over this period, the global economy was heavily preoccupied with these trade tensions, which affected investment decisions and impacted supply chains, including in countries supplying raw materials and intermediates to China for final processing and export to the U.S.

Eventually, an agreement in principle on a Phase-1 trade deal was reached in mid-December 2019, signed on January 15, 2020, to take effect from February 15. Under this agreement, China would buy $200 billion more of U.S. goods and services over the following two years and remove barriers to various U.S. exports. The U.S. agreed to suspend an additional 15 per cent tariff to be imposed on around $162-billion worth of imports from China and reduce some newly imposed duties.

However, the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan from January 2020 affected some of these equations. Chinese officials have maintained that they would definitely honour the commitments for agricultural imports from the U.S. (worth around $32 billion) but additional purchases of manufacturing and energy goods could be affected, if China had to invoke the force majeure clause because of the pandemic.

However, since then, China has continued to make positive overtures to the U.S. on the trade front. As recently as May 12, it announced tariff exemptions on 79 American products, including ores, chemicals and certain medical products, and allowed imports of barley and blueberries on May 14.

Present scenario

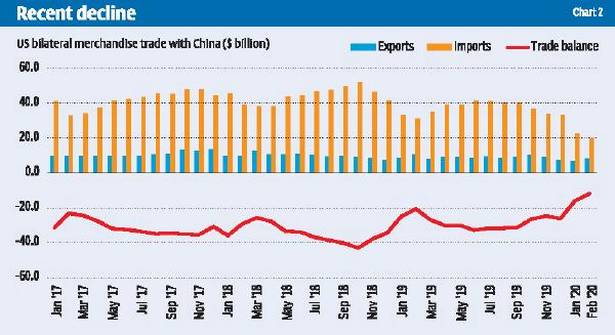

But as Chart 2 indicates, the U.S. bilateral deficit with China had been falling from mid-2019, well before the trade deal was signed, and by January 2020 it was one-third lower than the monthly peak achieved in September 2018. Since then, of course, the pandemic affected Chinese exports to the U.S., and subsequent lockdowns across the world affected trade drastically, and so the bilateral deficit fell even further to less than $12 billion in February 2020.

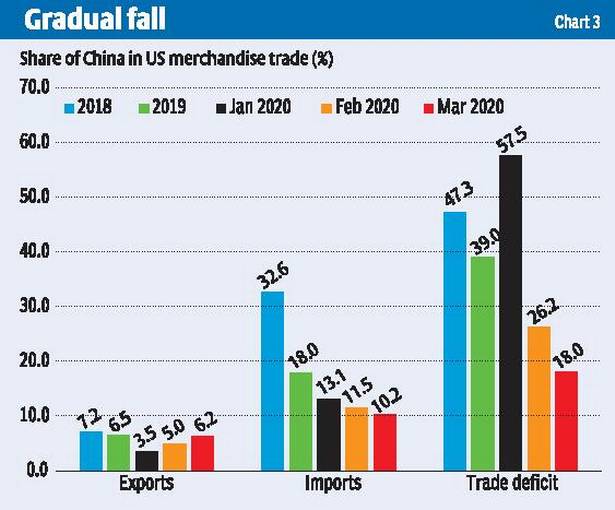

Essentially, the share of China in U.S. trade has fallen sharply from 2018. Chart 3 provides some of the most recent data, suggesting that by March 2020, only 10 per cent of U.S. merchandise imports came from China, which accounted for less than one-fifth of the U.S. merchandise trade deficit.

Incidentally, the U.S. continues to maintain a healthy surplus on trade in services: in 2019 this amounted to nearly $250 billion in the aggregate and was also significant for trade with China.

Root cause

Despite all this, Trump has only ratcheted up the rhetoric against China in recent months, accusing the country of suppressing vital information about the virus that allowed the subsequent spread, and even allowing discredited rumours about its origins in a Wuhan lab. This reveals the real purpose of the conflict: it was never really about trade per se, but about technology, and the U.S. fears that China is emerging as a technological superpower in its own right, with the possibility of challenging U.S. dominance in the near future.

This also explains the unfortunate bipartisan support for anti-China positions in the U.S. government. The opening of the latest front in the “trade war” makes this very explicit. On May 15, the Trump administration announced that it would ban Chinese company Huawei from using U.S. software and hardware in strategic semiconductor processes. This followed a one-year extension of the export ban on Huawei and ZTE. Trump has also been pressurising European governments to refrain from collaborating with Huawei in particular.

These moves are designed to prevent the Chinese chip, software and telecom companies from expanding their markets and increasing their technological capabilities, in what is increasingly seen as the most promising new frontier for a world economy in decline.

All the signs are that the U.S.-China trade deal will have to be renegotiated, with uncertain outcomes. As global trade collapses because of the impact of the pandemic and associated containment measures, this is one more negative impetus that will prevent recovery any time soon.