Richard Heinberg is a very important scholar and an apparently lovely human being. His books are always penetrating, and both his contribution to and his review of Michael Moore’s corporate-green-censored movie, Planet of the Humans, demonstrate his continuing efforts to speak crucially unheard truths.

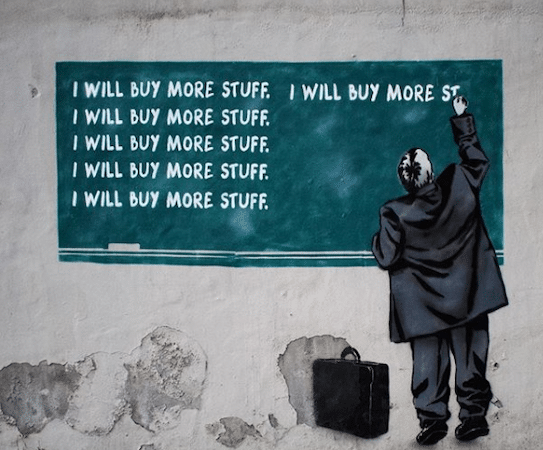

So, here at TCT, we have to ask: Mr. Heinberg, what’s up with this?:

So, here at TCT, we have to ask: Mr. Heinberg, what’s up with this?:

A “consumer economy”? Really? Your analysis is that “consumers,” the aggregated acquirers and users of goods and services, are in charge of “our” economy?

This, of course, is a hypothesis, not an indisputable fact. Its natural and obvious rival is the assertion that we actually live in a “capitalist economy,” i.e., a productive-and-distributional order in which money-investors, not product-users, tend to dominate the course of events.

It remains fascinating (and disheartening) to see even courageous and insightful figures like Richard Heinberg continue to opt for the “consumer economy” framing of reality.

Anybody who does this does, ipso facto, two rather remarkable things:

- They radically de-emphasize capitalists and capitalism as causal factors. Indeed, it isn’t much of an exaggeration to say that “consumer culture/economy/society” theorists more or less adopt the quasi-official capitalist view of reality. Capitalists, after all, have always claimed that, notwithstanding both their own command of strategic assets and their multi-trillion-dollar-a-year marketing endeavors, they are mere servants of pre-existing, independently-arising “consumer demand.” Talking about a “consumer culture/economy/society” all but concedes this extremely self-serving and debatable claim.

- They ignore the long, if not very well-known, body of thought on the various ways in which “our” capitalist economy does not, in fact, embody and serve the basic interests of product users. Names like Thorstein Veblen (whose most-read [only-read?] work is his first and by far worst one), Vance Packard, Baran and Sweezy, Marvin Harris, and Giles Slade? In the “consumer culture/economy/society” frame, such seminal iconoclastic thinkers are all flushed away, as is the crucial question of how their works might be extended and refined.

My own guess is that, by choosing “consumer” over “capitalist,” well-meaning and important thinkers like Richard Heinberg somehow imagine they are making their ideas more palatable to a wider audience, on the thesis that talking about capitalism is just too radical.

But reality is reality, no matter how fearful of describing it we’ve all been trained to be. And we aren’t likely to sweet-talk our way around human history’s richest and most deniable power structure. Either we start talking about the Emperor and His Old/New Clothes, or we don’t.

“Consumer economy” is a way of doing the latter.