The excessive use of force and killings of unarmed Black Americans by police has fueled a popular movement for slashing police budgets, reimagining policing, and directing freed funds to community-based programs that provide medical and mental health care, housing, and employment support to those in need. This is a long overdue development.

Police are not the answer

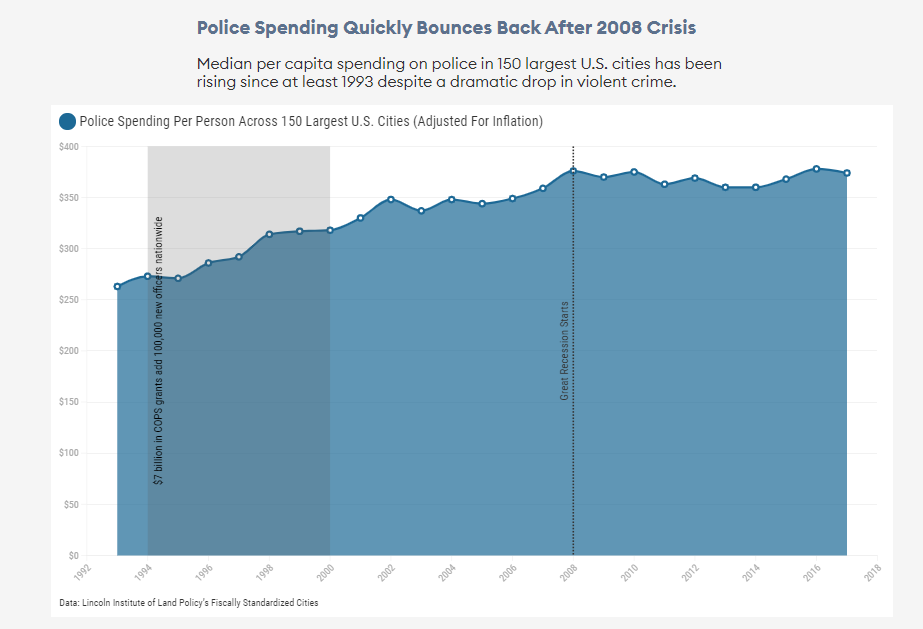

Police budgets rose steadily from the 1990s to the Great Recession and, despite the economic stagnation that followed, have remained largely unchanged. This trend is highlighted in the figure below, which shows real median per capita spending on police in the 150 largest U.S. cities. That spending grew, adjusted for inflation, from $359 in 2007 to $374 in 2017. The contrast with state and local government spending on social programs is dramatic. From 2007 to 2017, median per capita spending on housing and community development fell from $217 to $173, while spending on public welfare programs fell from $70 to $47.

Thus, as economic developments over the last three decades left working people confronting weak job growth, growing inequality, stagnant wages, declining real wealth, and rising rates of mortality, funding priorities meant that the resulting social consequences would increasingly be treated as policing problems. And, in line with other powerful trends that shaped this period–especially globalization, privatization, and militarization–police departments were encouraged to meet their new responsibilities by transforming themselves into small, heavily equipped armies whose purpose was to wage war against those they were supposed to protect and serve.

The military-to-police pipeline

The massive, unchecked militarization of the country and its associated military-to-police pipeline was one of the more powerful factors promoting this transformation. The Pentagon, overflowing with military hardware and eager to justify a further modernization of its weaponry, initiated a program in the early 1990s that allowed it to provide surplus military equipment free to law enforcement agencies, allegedly to support their “war on drugs.” As a Forbes article explains:

Since the early 1990s, more than $7 billion worth of excess U.S. military equipment has been transferred from the Department of Defense to federal, state and local law enforcement agencies, free of charge, as part of its so-called 1033 program. As of June [2020], there are some 8,200 law enforcement agencies from 49 states and four U.S. territories participating.

The program grew dramatically after September 11, 2001, justified by government claims that the police needed to strengthen their ability to combat domestic terrorism. As an example of the resulting excesses, the Los Angeles Times reported in 2014 that the Los Angeles Unified School District and its police officers were in possession of three grenade launchers, 61 automatic military rifles and a Mine Resistant Ambush Protected armored vehicle. Finally, in 2015, President Obama took steps to place limits on the items that could be transferred; tracked armored vehicles, grenade launchers, and bayonets were among the items that were to be returned to the military.

President Trump removed those limits in 2017, and the supplies are again flowing freely, including armored vehicles, riot gear, explosives, battering rams, and yes, once again bayonets. According to the New York Times, “Trump administration officials said that the police believed bayonets were handy, for instance, in cutting seatbelts in an emergency.”

Outfitting police departments for war also encouraged different criteria for recruiting and training. For example, as Forbes notes, “The average police department spends 168 hours training new recruits on firearms, self-defense, and use of force tactics. It spends just nine hours on conflict management and mediation.” Arming and training police for military action leads naturally to the militarization of police relations with community members, especially Black, Indigeous and other people of color, who come to play the role of the enemy that needs to be controlled or, if conditions warrant, destroyed.

In fact, the military has become a major cheerleader for domestic military action. President Trump, on a call with governors after the start of demonstrations protesting the May 25, 2020 killing of George Floyd while in police custody, exhorted them to “dominate” the street protests.

As the Washington Examiner reports:

“You’ve got a big National Guard out there that’s ready to come and fight like hell,” Trump told governors on the Monday call, which was leaked to the press.

[Secretary of Defense] Esper lamented that only two states called up more than 1,000 Guard members of the 23 states that have called up the Guard in response to street protests. The National Guard said Monday that 17,015 Guard members have been activated for civil unrest.“I agree, we need to dominate the battle space,” Esper said after Trump’s initial remarks. “We have deep resources in the Guard. I stand ready, the chairman stands ready, the head of the National Guard stands ready to fully support you in terms of helping mobilize the Guard and doing what they need to do.”

The militarization of the federal budget

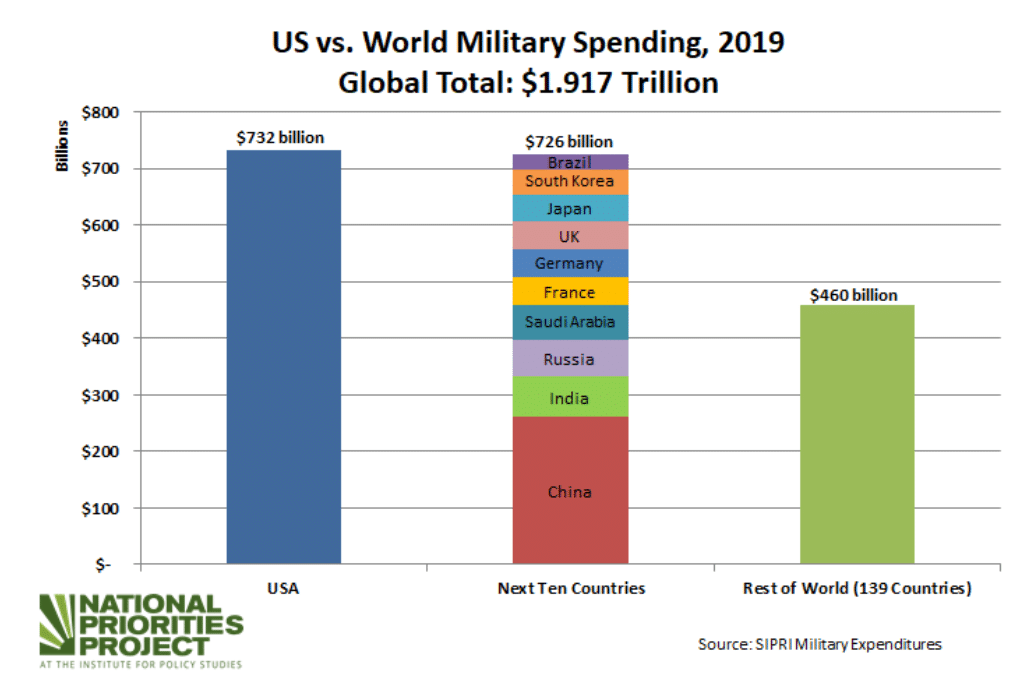

The same squeeze of social spending and support for militarization is being played out at the federal level. As the National Priorities Project highlights in the following figure, the United States has a military budget greater than the next ten countries combined.

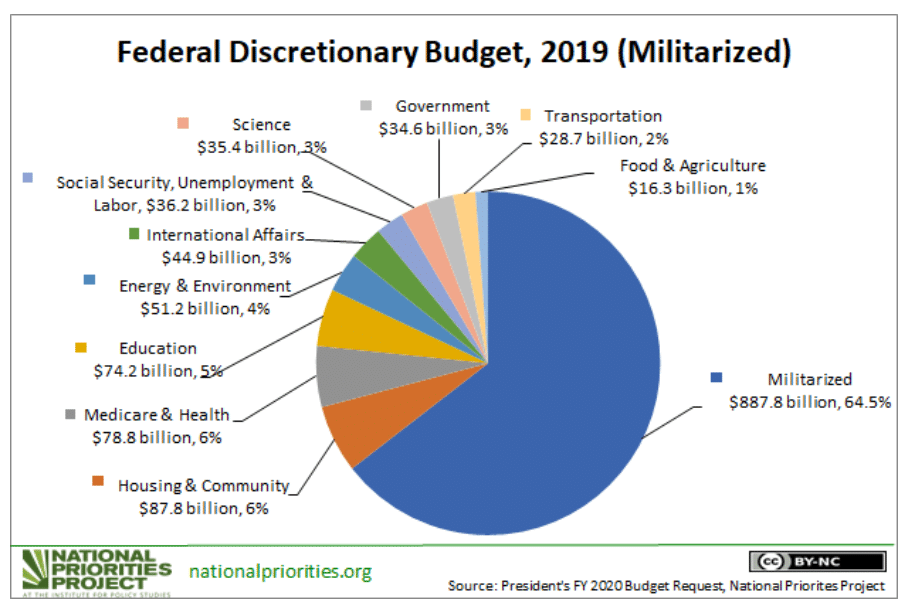

Yet, this dominance has done little to slow the military’s growing hold over federal discretionary spending. At $730 billion, military spending accounts for more than 53 percent of the federal discretionary budget. A slightly broader notion, what the National Priorities Project calls the militarized budget, actually accounts for almost two-thirds of the discretionary budget. The militarized budget:

includes discretionary spending on the traditional military budget, as well as veterans’ affairs, homeland security, and law enforcement and incarceration. In 2019, the militarized budget totaled $887.8 billion–amounting to 64.5 percent of discretionary spending. . . . This count does not include forms of militarized spending allocated outside the discretionary budget, include mandatory spending related to veterans’ benefits, intelligence agencies, and interest on militarized spending.

The militarized budget has been larger than the non-militarized budget every year since 1976. But the gap between the two has grown dramatically over the last two decades.

In sum, the critical ongoing struggle to slash police budgets and reimagine policing needs to be joined to a larger movement against militarism more generally if we are to make meaningful improvements in majority living and working conditions.