Lying in State: Why Presidents Lie—and Why Trump Is Worse

Basic Books, 2020

It is perhaps telling that the first known presidential lie in our nation’s history occurred just one year into the office’s history—and revolved around a deceptive campaign to square the new nation’s lofty founding principles with its ugly accommodation of chattel slavery.

Recently sworn-in President George Washington faced a dilemma in 1790 after the U.S. capital was moved from New York City to Philadelphia, because Pennsylvania state law decreed that all enslaved persons would be automatically freed after residing in the state for six straight months. Rather than accept his new home’s gradual abolitionism, our first Founding Father undertook a particularly craven scheme to circumvent the rule, by periodically shipping his enslaved servants back and forth to Virginia to reset their residency clock, and thus avoid having to manumit a single one of them.

It amounted to a cruel, 18th-century equivalent of a modern-day—and dare we say, Trumpian—tax-avoidance scam. And Washington all but admitted as much in a blunt letter to his plantation manager: “I wish to have it accomplished under pretext that may deceive both them and the Public.”

With that, a long and tragically counterproductive American political tradition was born.

That’s clearly the takeaway from Eric Alterman’s latest book, Lying in State: Why Presidents Lie—and Why Trump Is Worse (Basic Books), which offers up that anecdote as but the first in a punishingly long and maddening list of White House lies and distortions. The book culminates, naturally, with an entire section devoted to the unprecedented disregard for facts and truth shown by the 45th president.

Alterman’s latest book serves as an expanded and updated version of his 2004 look at the same subject, When Presidents Lie. In that book, the Nation columnist and Brooklyn College journalism professor examined several landmark moments of presidential deception in the 20th century, from Franklin Roosevelt misrepresenting his concessions at the Yalta conference, to Lyndon Johnson effectively concocting the Gulf of Tonkin incident to justify expanding the Vietnam War, to the infamously chimerical weapons of mass destruction used by George W. Bush as a false pretext for the invasion of Iraq.

Lying in State reprises some of his previous work’s themes—foremost of which is that presidential lies are almost guaranteed to backfire spectacularly—but also digs deeper into the broader causes of the phenomenon. True to his media critic roots, Alterman also weaves in how the country’s corporate media often act as willing enablers to incessant White House attempts to deceive the polity. In fact, Alterman not only directly implicates a complaisant press in presidential deception, but illustrates how “both sides,” false equivalence–fetishizing journalism set the conditions for the inevitable arrival of someone like Trump to the highest elected office in the land.

Alterman briefly zeroes in on the executive editor of the New York Times, Dean Baquet, at the end of the book, as an exemplar of the timid and defensive crouch adopted by so many mainstream editorial mastheads. On multiple occasions in the era of Trump, Baquet has defended his newspaper’s stubborn refusal to use the words “lie” or “lying” when covering this president’s onslaught of willful disinformation, except in the most extremely egregious cases (New York Times, 6/25/18) . In an online discussion with readers, Baquet explained his journalistic worldview:

Most politicians obfuscate or exaggerate at times. But I wouldn’t use the word “lie” in a news story in cases like that. I don’t think we should use that word every day in the New York Times.

This goes beyond normalizing lies to a kind of learned helplessness about them, and it’s tantamount to unilateral surrender when faced with a president who shows no compunction about lying on a daily, hourly or even minute-by-minute basis. (One notable exception to Baquet’s dare-not-call-them-lies rule came right after the 2016 election, when Trump repeatedly claimed to have been cheated out of a popular vote majority by illegal voting—New York Times, 1/23/17—which foreshadowed Trump’s ongoing propaganda campaign that the 2020 version will be rife with electoral fraud as well.) Ironically, this insistence on eliding or excusing lies whenever possible, and employing tortured euphemisms instead, is now de rigueur among the very reporters and editors who are exposed to Trump’s lies the most—among them, the Times’ own White House correspondent.

But before Lying in State begins its deeply researched, historical review of presidential lying (and journalistic fecklessness) through the decades, it establishes an instructive, if cheeky, taxonomy of lying, borrowing from the work of some well-known philosophers. The first among this dubious group is Thomas Carson’s “bald-faced lies,” statements that both the liar and his or her intended audience implicitly understand to be untrue: think Trump’s transparently phony, “Mexico will pay for the border wall” applause line. Another subspecies: Harry Frankfurt’s not-so-subtly named “bullshit,” which defines anything that is obviously unprovable or displays an utter disregard for reality, such as Trump’s absurd, much-evidence-to-the-contrary boast that he is “the least racist person in the world,” or his nonsense assertion that the noise from windmills causes cancer.

The final two examples come from Jürgen Habermas, who highlights the sins of misinformation and disinformation, the latter differing from the former by its clear intent to deceive. Compare Trump’s weeks-long touting of hydroxychloroquine as a potential “game changer” for treating COVID-19, which Trump quite likely might actually believe, versus his more recent, knowingly baseless claim that mail-in voting is rife with fraud and yet is somehow functionally different than absentee voting, which he simultaneously deems perfectly acceptable.

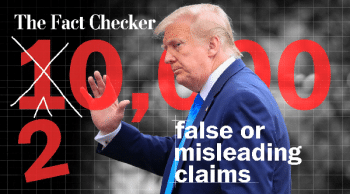

The Washington Post (7/13/20) has compiled a list of 20,000 false or misleading claims” by Donald Trump.

As those easily provided examples suggest, the current president really is sui generis when it comes to the breadth and depth of his presidential lies—having now made more than 20,000 “false or misleading claims” since his inauguration, according to the Washington Post’s factchecker (7/13/20). Trump’s tsunami of lies, often in service of covering up his thoroughly corrupt conduct, doubtless represents a unique threat to the American democracy—as the book’s subtitle warns. Yet the most valuable lesson from Lying in State comes from connecting Trump’s rampant trampling of the truth to the same patterns and motives as his many prevaricating predecessors.

This corrosive through-line predates both the presidency and the nation itself, and traces back to the arrival of the first slave ship to our shores in 1619, as Alterman explains:

The racist assumptions underlying the ideology of white supremacy have remained, for the most part, just below the surface of American political life. Yet these beliefs have profoundly contradicted Americans’ understanding of themselves and their professed belief that “all men are created equal.” Rather than confront this contradiction, American presidents have felt it necessary to elide it with lies.

As the reader proceeds through the book’s damning history, this disconnect rides alongside, haunting our nation’s presidential decisions time and again. For the first 100 years, it is the Constitution’s “original sin” of slavery, and its racist companion, a relentlessly expanisionist Manifest Destiny, that are the primary drivers of the biggest lies coming from the White House. To preserve both of these policies, presidents from Thomas Jefferson to William McKinley routinely chose to deceive the public about their true intentions—and their consequences—while subjugating and killing untold numbers of peoples in forced migrations, and conducting wars of conquest across the continent and then further overseas.

After the turn of the 20th century, these two motivations to lie metastasized into protecting both the Jim Crow laws that were the systemically racist progeny of slavery, and the enormous fig leaf of “national security” necessitated by a now openly zealous imperialism. Ironically, though President Woodrow Wilson was instrumental in this pivot, Alterman doesn’t spot any specific examples of Wilson personally lying to the American public. (The same cannot be said for his wife, however, who, in a shockingly bold deception, covered up a massive stroke that completely incapacitated Wilson, while she effectively ran the country and most likely forged his signature on Prohibition legislation.)

The USS Maddox, which Lyndon Johnson lied about being attacked by North Vietname in the Gulf of Tonkin. (photo: U.S. Navy)

With World War II and the sprawling national security apparatus that followed it in the Cold War era, presidential lies jumped by orders of magnitude. Korea, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Vietnam, Watergate, Iran/Contra: All of these major historical events were accompanied by, if not actually founded upon, a raft of official lies of commission and omission. And for every well-known example, the book dredges up just as many sordid White House lies about more obscure U.S. foreign policy abuses, in places like Guatemala, El Salvador, Iran, Angola and Chile.

All of this past was prologue, then, to bring us to the White House doorstep of the 45th president. When Donald Trump re-appears in the book, after a grim 250 pages of presidential deceit, his willingness to distort reality to advance his racism, xenophobia, corruption, militarism and gross personal misconduct seems less of a shock to the political system and more like a natural evolution. Trump, in other words, is the toxic by-product of 400 years of corrosive American self-deception, helped along by a sclerotic press corps that meekly absorbs lies rather than challenges them.

Our already frail democracy, beset by what the book’s final chapter rightly sums up as “System Overload,” faces a momentous turning point in 2020. And we can’t say we haven’t been warned. Yale history professor Timothy Snyder, in a Vox discussion (5/22/17) of his powerfully prescient 2017 book, On Tyranny, limned how a relentless assault on the truth creates a slippery slope that can threaten the very foundations of a nation and the freedom of its people:

The way it works is that you first just lie a lot. You fill up the public space with things that aren’t true, as Trump has obviously done. Next you say, “It’s not me who lies; it’s the crooked journalists. They’re the ones who spread the fake news.” Then the third step, if this works, is that everybody shrugs their shoulders and says, “Well, we don’t really know who to trust; therefore, we’ll trust whoever we feel like trusting.” In that situation… authoritarianism wins.

But even if the country expels Trump from the White House this November, the dangerous precedents he has set and the distortion field of dishonesty he has created may well remain. It will not be enough to simply return to “normal”; the boundaries of where official deception can travel have now been pushed too far for that, Alterman notes.

Like the virus that is currently ravaging our republic, Trump is not something that we must aspire to merely survive. Not if our democracy is to be truly restored to health. Instead, both the American people and the press will have to confront some hard, uncomfortable truths about our past and the lies we have told ourselves. Only then will we have begun to inoculate ourselves against the next president’s lies.