Since the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis earier this year, we have witnessed the largest mass uprising in the United States’ recent history with millions taking to the streets day in and day out. This has included massive rallies, street battles, and tearing down statues of racist. The police have met these protests with brutal force. The uprisings continued following the attempted murder of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin and the subsequent murder of two protesters in Kenosha by 17-year-old white nationalist Kyle Rittenhouse.

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement originated from the 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman for the murder of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Florida. The movement has continued because of the countless killings of Black people at the hands of law enforcement. Following the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, BLM grew more and more militant. Just like today, protesters called for justice, defunding, and even abolishing the police. BLM may have begun in 2013 but is part of the long history of Black resistance since the first slave ships arrived onto Turtle Island.

These events are nothing new for a country founded on white supremacy, genocide, and slavery. Even so, some might be surprised that the current uprising started in the North, specifically the Great Lakes region. In order to understand the uprisings, one must grapple with the commonly held myth that institutional racism is exclusive to the South. Indeed, U.S. cultural memory seems to embrace the defeat of the South in the U.S. Civil War as an exoneration of the North. It goes without saying that the North has racism baked into its core. The contemporary and historical experiences of Black Americans in the North–especially in the Great Lakes region–show how true this is.

Everyday Life in the Racist North

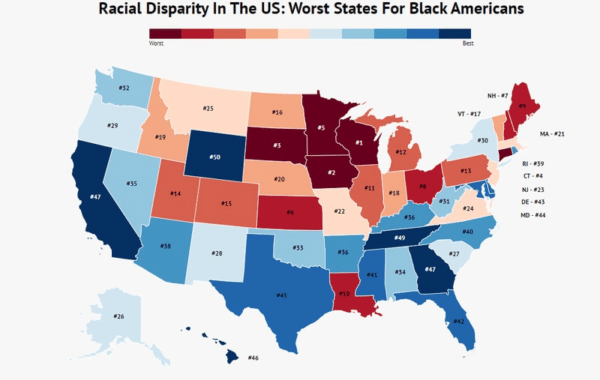

A recent study found that Wisconsin was the worst place for Black Americans, and Minnesota lagged not far behind at number five. A 2019 Brookings Institut e study found that Milwaukee (just north of Kenosha) was the most racially segregated metro area in the United States. In fact, the five most racially-segregated cities were in the North, with four (Milwaukee, Detroit, Chicago, and Cleveland) in the Great Lakes region.

The data underscores how systemic racism goes well beyond the land of Dixie. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, Black people constitute 38% of Wisconsin’s prison population, even though they represent only 6% of the state’s population. In Minnesota, 31% of the prison and jail population is Black, while making up only 5% of the state’s population. Though not as staggering, Latinx and Indigenous people are disproportionately represented in prisons and jails in both Minnesota and Wisconsin as well.

Historical injustices are further reflected in the racial wealth gap. Considered property for centuries, Black Americans were not allowed to own property. The Institute of Policy Studies found that the median wealth for White households in 2016 was $146,984 and for Black Americans it was an astonishingly low $3,557. These researchers found that White wealth has skyrocketed in the last two decades while Black American wealth has decreased. Wisconsinites and Minnesotans will brag how great their states are to raise a family, but this data begs the question: whose families?

History of Systemic Anti-Black Racism in the North

The Great Migration at the outset of the Twentieth Century brought millions of Black Americans from the South to the industrial North, settling in large numbers in places like Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and other cities. Black Americans came for jobs and to flee racial violence including lynchings. Although many of these migrants’ lives were improved in the short term, the threat of racial violence still loomed.

As Black Americans migrated northwards in greater numbers, the practice of redlining— refusing to lend mortgages to Black Americans in specific neighborhoods–barred them from huge swathes of cities, segregating them into concentrated and inherently impoverished areas instead. This legal practice ended with the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which came about as a result of pressure from the Black Freedom Movement. The growing racial wealth gap proves, however, this was far from the end of financial discrimination. Black Americans and other people of color have continued to face hurdles when applying for loans, and were disproportionately targeted by predatory lending practices in the lead up to the 2008-2009 economic crisis.

Though the North may not have had the segregated entrances or bathrooms of the Jim Crow South, life was nonetheless governed by a violent enforcement of racial separation. One clear example were the Chicago race riots of 1919, sparked after a White man murdered a Black American boy for crossing an invisible segregated line while swimming in Lake Michigan. Not surprisingly, the police did not arrest the man. After the dust settled, 38 people were dead.

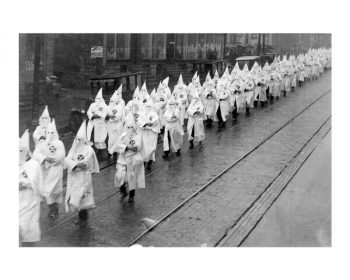

Even the most racist institutions of the South like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) have found a home in the North. In the 1920s, the KKK made its first appearance in Wisconsin, organizing rallies to win fellow white supremacists to their cause. In 1997, a large Klan rally was organized in Beloit, Wisconsin, an industrial town on the Illinois border. The terror of the KKK still exists today throughout the Great Lakes region.

It is no surprise that the KKK’s numbers rose alongside the growth in sundown towns. These were all-white towns that would not allow Black Americans after sunset. In Wisconsin, most towns (with the exception of urban centers like Milwaukee and Madison) were sundown towns. Violence was necessary for the enforcement of sundown towns. Minnesota was no different. In 1920, three Black circus workers were dragged from jail in Duluth and hanged from a telephone poll as police watched. Though oftentimes Black Americans were the targets, plenty of sundown towns throughout the U.S. would have the same practice toward Indigenous people, Mexicans, Chinese, Japanese, or any non-White person.

It is no surprise that the KKK’s numbers rose alongside the growth in sundown towns. These were all-white towns that would not allow Black Americans after sunset. In Wisconsin, most towns (with the exception of urban centers like Milwaukee and Madison) were sundown towns. Violence was necessary for the enforcement of sundown towns. Minnesota was no different. In 1920, three Black circus workers were dragged from jail in Duluth and hanged from a telephone poll as police watched. Though oftentimes Black Americans were the targets, plenty of sundown towns throughout the U.S. would have the same practice toward Indigenous people, Mexicans, Chinese, Japanese, or any non-White person.

This racial antagonism was reflected in the relationship with Indigenous people, who have long faced unique battles with racism in the Great Lakes region. It was common in Northern Wisconsin in the 1980s to see signs that said, “Save a Walleye, Spear an Indian” as conflicts rose between White settlers and Anishinaabeg people for exercising their treaty rights.

With violence there is always resistance. The American Indian Movement was founded in Minneapolis in 1968 to combat police violence against the Indigenous community and actively worked with the Black Panther Party. In Chicago the Black Panther Party built the Rainbow Coalition with the Young Lords, a militant Puerto Rican organization, and the Young Patriots Organization, composed of displaced White Appalachians, to combat police violence and poverty. These powerful examples are a reminder that resistance to racial violence has also always existed in the North.

With violence there is always resistance. The American Indian Movement was founded in Minneapolis in 1968 to combat police violence against the Indigenous community and actively worked with the Black Panther Party. In Chicago the Black Panther Party built the Rainbow Coalition with the Young Lords, a militant Puerto Rican organization, and the Young Patriots Organization, composed of displaced White Appalachians, to combat police violence and poverty. These powerful examples are a reminder that resistance to racial violence has also always existed in the North.

Moving Forward

As today’s uprisings continue and the call to defund and even abolish the police gains more steam, one must grapple with the North’s racist history. The North, and the Democratic elite who govern most of the region’s cities, would prefer to maintain the myth that racism is exclusive to the South. If this were the case, these murders would merely be brutal acts against humans rather than a direct product of systemic racism.

Instead, Democratic lawmakers in places like Chicago, Minneapolis, Madison, and Milwaukee double down on these systems, displaying an unquestioned loyalty to police unions while cutting social services. Now, these lawmakers would like you to forget their racist policy decisions as they attempt to convert street protest to votes. The Democrats in office did not spark the anti-racist movement, it was the people in the streets demanding change. In order to fight racism in the US, we must have no illusions about where power lies. Racism must be confronted in both the North and the South.

As Malcolm X said in his The Ballot or the Bullet speech in Detroit, Michigan on April 12, 1964: “As long as you south of the Canadian border, you south.”