Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

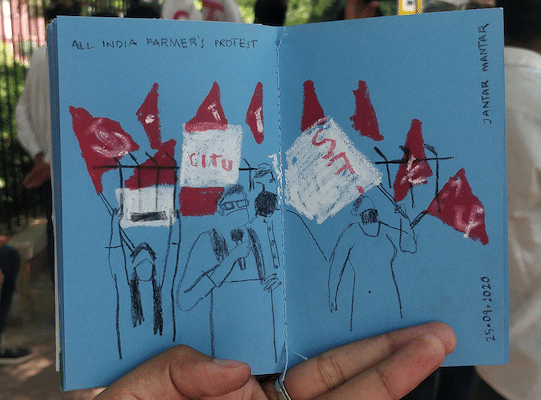

Farmers and agricultural workers from northern India marched along various national highways toward India’s capital of New Delhi as part of the general strike on 26 November. They carried placards with slogans against the anti-farmer, pro-corporate laws that were passed by India’s Lok Sabha (lower house of parliament) in September, and then pushed through the Rajya Sabha (upper house) with only a voice vote. The striking agricultural workers and farmers carried flags that indicated their affiliation with a range of organisations, from the communist movement to a broad front of farmers’ organisations. They marched against the privatisation of agriculture, which they argue undermines India’s food sovereignty and erodes their ability to remain agriculturalists.

Roughly two-thirds of India’s workforce derives its income from agriculture, which contributes to roughly 18% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP). The three anti-farmer bills passed in September undermine the minimum support price buying schemes of the government, put 85% of the farmers who own less than 2 hectares of land at the mercy of bargaining with monopoly wholesalers, and will lead to the destruction of a system that has till now maintained agricultural production despite erratic prices for food produce. One hundred and fifty farmer organisations came together for their march on New Delhi. They pledge to stay in the city indefinitely.

Around 250 million people across India joined the general strike on 26 November, making it the largest strike in world history. If those who struck formed a country, it would be the fifth largest in the world after China, India, the United States, and Indonesia. Industrial belts across India–from Telangana to Uttar Pradesh–came to a halt, as workers in the ports from the Jawaharlal Nehru Port (Maharashtra) to the Paradip Port (Odisha) stopped work. Coal, iron ore, and steel workers put down their tools, while trains and buses stood idle. Informal sector workers joined in, and so did health care workers and bank employees. They struck in opposition to labour laws that extend the working day to twelve hours and strike down labour protections for 70% of the workforce. Tapan Sen, the general secretary of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions, said, ‘The strike today is only a beginning. Much more intense struggles will follow’.

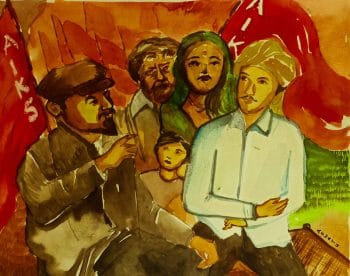

Nehal Ahmed (India), Cold Nights, High Spirits. Farmers from Punjab who have joined the movement against the farm laws passed by the Modi government. Delhi-Haryana border at Singhu, India, November 2020.

The pandemic has deepened the crisis of the Indian working class and peasantry, including the richer farmers. Despite the dangers of the pandemic, out of a great sense of desperation, workers and peasants gathered in public spaces to tell the government that they had lost confidence in them. The film actor Deep Sindhu joined the protest, where he told a police officer, ‘Ye inquilab hai. This is a revolution. If you take away farmers’ land, then what do they have left? Only debt’.

Along the rim of New Delhi, the government positioned police forces, barricaded the highways, and prepared for a full-scale confrontation. As the long columns of farmers and agricultural workers approached the barricades and appealed to their brethren who had set aside the clothes of farmers and put on police uniforms, the authorities fired tear gas and water cannons at the farmers and agricultural workers.

The day of the general strike of farmers and workers, 26 November, is also Constitution Day in India, which marks a great feat of political sovereignty. Article 19 of the Indian Constitution (1950) quite clearly gives Indian citizens the right to ‘freedom of speech and expression’ (1.a), the right to ‘assembly peaceably and without arms’ (1.b), the right to ‘form associations or unions’ (1.c), and the right ‘to move freely throughout the territory of India’ (1.d). In case these articles of the Constitution had been forgotten, the Indian Supreme Court reminded the police in a 2012 court case (Ramlila Maidan Incident vs. Home Secretary) that ‘Citizens have a fundamental right to assembly and peaceful protest, which cannot be taken away by an arbitrary executive or legislative action’. The police barricades, the use of tear gas, and the use of water cannons–infused with the Israeli invention of yeast and baking powder to induce a gagging reflex–violate the letter of the Constitution, something that the farmers yelled to the police forces at each of these confrontations. Despite the cold in northern India, the police soaked the farmers with water and tear gas.

Dharampal Seel, a senior Kisan Sabha leader from Punjab, uses his Red Flag to push a tear gas canister, 27 November 2020.

But this did not stop them, as brave young people jumped on the water cannon trucks and turned off the water, farmers drove their tractors to dismantle the barricades, and the working class and the peasantry fought back against the class war imposed on them by the government. The twelve-point charter of demands put forward by the trade unions is sincere, having captured the sentiments of the people. The demands include the reversal of the anti-worker, anti-farmer laws pushed by the government in September, the reversal of the privatisation of major government enterprises, and immediate relief for the population, which is suffering from economic hardship provoked by the coronavirus recession and years of neoliberal policies. These are simple demands, humane and true; only the hardest hearts turn away from them, responding instead with water cannons and tear gas.

These demands for immediate relief, for social protections for workers, and for agricultural subsidies appeal to workers and peasants around the world. It is demands such as these that provoked the recent protests in Guatemala and that led to the general strike on 26 November in Greece.

We are now entering a period in this pandemic when more unrest is possible as more people in countries with bourgeois governments get increasingly fed up with the atrocious behaviour of their elites. Report after report shows us that the social divides are getting more and more extreme, a trend that began long before the pandemic but has grown wider and deeper as a consequence of it. It is only natural for farmers and agricultural workers to be agitated. A new report from the Land Inequality Initiative shows that only 1% of the world’s farms operate more than 70% of the world’s farmland, meaning that massive corporate farms dominate the corporate food system and endanger the survival of the 2.5 billion people who rely upon agriculture for their livelihood. Land inequality, when it considers landlessness and land value, is highest in Latin America, South Asia, and parts of Africa (with notable exceptions such as China and Vietnam, which have the ‘lowest levels of inequality’).

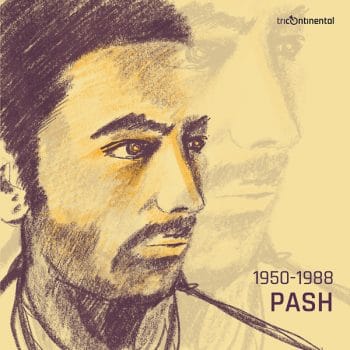

A young man, Avtar Singh Sandhu (1950-1988), read Maxim Gorky’s Mother (1906) in the early 1970s in Punjab, from where many of the farmers and agricultural workers travelled to the barricades around New Delhi. He was very moved by the relationship between Nilovna, a working-class woman, and her son, Pavel, or Pasha. Pasha finds his feet in the socialist movement, brings revolutionary books home, and, slowly, both mother and son are radicalised. When Nilovna asks him about the idea of solidarity, Pasha says, ‘The world is ours! The world is for the workers! For us, there is no nation, no race. For us, there are only comrades and foes’. This idea of solidarity and socialism, Pasha says, ‘warms us like the sun; it is the second sun in the heaven of justice, and this heaven resides in the worker’s heart’. Together, Nilovna and Pasha become revolutionaries. Bertolt Brecht retold this story in his play Mother (1932).

Avtar Singh Sandhu was so inspired by the novel and the play that he took the name ‘Pash’ as his takhallus, his pen name. Pash became one of the most revolutionary poets of his time, murdered in 1988 by terrorists. I am grass is among the poems he left behind:

Bam fek do chahe vishwavidyalaya par

Banaa do hostel ko malbe kaa dher

Suhaagaa firaa do bhale hi hamari jhopriyon par

Mujhe kya karoge?

Main to ghaas hun, har chiz par ugg aauungaa.

If you wish, throw your bomb at the university.

Reduce its hostel to a heap of rubble.

Throw your white phosphorus on our slums.

What will you do to me?

I am grass. I grow on everything.

That’s what the farmers and the workers in India say to their elites, and that is what working people say to elites in their own countries, elites whose concern–even in the pandemic–is to protect their power, their property, and their privileges. But we are grass. We grow on everything.

That’s what the farmers and the workers in India say to their elites, and that is what working people say to elites in their own countries, elites whose concern–even in the pandemic–is to protect their power, their property, and their privileges. But we are grass. We grow on everything.

In the next week, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research will host two events with The People’s Forum. On 4 December, cultural workers from Venezuela, South Africa, and China/Canada will discuss art making for people’s struggles in times of CoronaShock. The discussion will highlight the Anti-Imperialist Poster Exhibition; the last of the four exhibitions launched today on the concept of the hybrid war includes artwork from 37 artists from 18 countries across the world. You can RSVP here.

On 8 December, the feminisms working group of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research will discuss the recently launched study, CoronaShock and Patriarchy, and the gendered impact of the pandemic. You can RSVP here.

Warmly,

Vijay