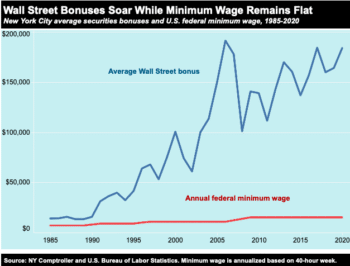

While low-wage workers are still waiting for a raise in the minimum wage, Wall Street employees enjoyed a 10 percent bump in their bonuses in the first year of the pandemic, according to new data from the New York State Comptroller.

Wall Street pay v. the minimum wage

Wall Street pay v. the minimum wage

- Since 1985, the average Wall Street bonus has increased 1,217 percent, from $13,970 to $184,000 in 2020. If the minimum wage had increased at that rate, it would be worth $44.12 today, instead of $7.25.

- The total bonus pool for 182,100 New York City-based Wall Street employees was $31.7 billion–enough to pay for more than 1 million jobs paying $15 per hour for a year.

- These bonuses come on top of salary and other forms of compensation. The average salary (with bonuses) for all securities industry employees in New York City was $406,700 in 2019. At the very top end, CEOs of the top five U.S. investment banks hauled in an average of $27.9 million in total compensation in 2019.

- Because the very rich can squirrel away much of their income, huge Wall Street bonuses don’t have nearly the stimulus effect as raising pay for low-wage workers who have to spend nearly every dollar they make.

Wall Street bonuses and gender and racial inequality

Wall Street bonuses and gender and racial inequality

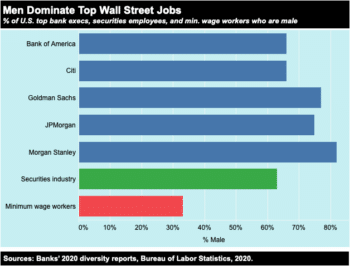

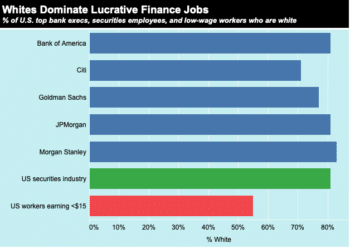

The rapid increase in Wall Street bonuses over the past several decades has contributed to gender and racial inequality, since workers at the low end of the wage scale are disproportionately people of color and women, while the lucrative financial industry is overwhelmingly white and male, particularly at the upper echelons.

- Nationwide, men make up 63 percent of all securities industry employees and 33 percent of the 1.1 million minimum wage workers.

- The CEOs of the five largest U.S. investment banks were all white men in 2020. The share of these banks’ senior executives and top managers who are male ranges from 66-82 percent. (JPMorgan Chase: 75%, Goldman Sachs: 77%, Bank of America: 66%, Morgan Stanley: 82%, and Citigroup: 66%)

- At the five largest U.S. investment banks, the share of senior executives and top managers who are white ranges from 71 to 83 percent. (JPMorgan Chase: 81%, Goldman Sachs: 77%, Bank of America: 81%, Morgan Stanley: 83%, and Citigroup: 71%)

- Nationally, securities industry employees are 80.5 percent white, 5.8 percent Black, 11.5 percent Asian, and 8.1 percent Latino. By contrast, whites make up an estimated 55.4 percent of people in jobs that pay less than $15 per hour.

Washington Inaction on Wall Street Pay and Minimum Wage

Washington Inaction on Wall Street Pay and Minimum Wage

Since 2010, the year the Dodd-Frank financial reform became law, regulators have failed to implement that law’s Wall Street pay restrictions and Congress has failed to raise the minimum wage. These two failures speak volumes about who has influence in Washington–and who does not.

Powerful Wall Street lobbyists have succeeded in blocking Section 956 of the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation, which prohibits financial industry pay packages that encourage “inappropriate risks.” Regulators were supposed to implement this new rule within nine months of the law’s passage but have dragged their feet–despite widespread recognition that these bonuses encouraged the high-risk behaviors that led to the 2008 financial crisis, costing millions of Americans their homes and livelihoods.

In 2011, regulators issued a proposed rule that did not go far enough to prevent the type of behavior that led to the 2008 crash. As spelled out in detail in Institute for Policy Studies comments to the SEC, the proposed rule fell short in several areas, including overly lenient bonus deferrals, weak stock-based pay restrictions, and enforcement proposals that leave too much discretion to bank managers. While regulators responded to criticism by agreeing to issue a new proposal, this work was not completed before the end of the Obama administration.

During the Trump administration, regulators put the issue on a back burner as Republicans maneuvered to get rid of the Wall Street pay restrictions altogether. In 2017, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Financial CHOICE Act, which would’ve repealed most of the Dodd-Frank reform package, including the Wall Street pay provision. Due to Democratic opposition in the Senate, the Wall Street deregulation bill that was adopted was significantly scaled back and did not affect financial industry pay.

Congress Should Build on the Modest Executive Pay Reform in the American Rescue Plan

In the American Rescue Plan Act passed in March 2021, Congress made a step forward in executive pay reform by expanding corporate tax deductibility limits on such compensation. Under the law, corporations will not be able to deduct any compensation exceeding $1 million paid to the 10 highest compensated employees, up from the current number of five executives. This is an important step towards eliminating taxpayer subsidies for excessive compensation. However, particularly for Wall Street firms, limiting the deductibility cap to just 10 employees is insufficient.

If average compensation for the 182,100 securities industry employees in New York is more than $400,000, then many thousands of Wall Street employees likely make more than $1 million. This would include high-powered traders with significant power over the stability of our financial system. Senators Jack Reed and Richard Blumenthal and Rep. Lloyd Doggett have introduced a bill that would expand the $1 million deductibility cap to all employees of publicly held corporations.

Another recently introduced bill, the Tax Excessive CEO Pay Act, would go further to incentivize firms to rein in pay at the top and lift up wages at the bottom. This proposal would increase the tax rate on corporations with large gaps between CEO and median worker pay, with the highest rate increase of five percentage points hitting companies with pay ratios of 500 to 1 or more.

In the new political landscape, lawmakers have a chance to end the Washington gridlock that has kept the federal minimum wage a poverty wage, while allowing the reckless bonus culture to continue to flourish on Wall Street–even during a pandemic.

Sarah Anderson directs the Global Economy Project at the Institute for Policy Studies and is a co-editor of the IPS web site Inequality.org.