Words for different flavors of trans people come and go, gathering different assortments of us together and drawing different lines between us. Sometimes the words have crisp edges of meaning; sometimes they’re blurred or shapeless. They fall in and out of fashion and sometimes reappear for another moment in the spotlight, with or without the tingle of nostalgia. Lately, “fem” is having a moment—sometimes as an umbrella term (“trans fems”), sometimes as a subcategory or add-on (“women and fems”), but almost always with a certain vagueness to it.

“Fem” matters because it comes from specific queer contexts and lineages that have a politics woven into their aesthetics. “Fem” matters right now because for cis gay, lesbian, and bisexual folks, that politics has largely been replaced by a version of queerness that retains only the label, substituting aesthetic markers for any actual pursuit of liberation. This depoliticizing move is rapidly expanding into many trans spaces. The stakes are high because the particular politics that “fem” named in its original contexts, and for trans women since then, is something we need right now.

North American queer and trans folks—especially white ones—who came up in the 1990s and early 2000s couldn’t help but encounter “fem” as part of a queer history of building our lives on our own terms. There was little possibility to be anything but actively in opposition to the straight and cis society around us. Since then a cis gay, lesbian, and bisexual conservatism has replaced liberation organizing with efforts towards assimilation through marriage and the military. The histories and the words that carry them have been drained of much of their meaning.

These days, “fem” has come to be used as a synonym for conventional femininity, and “queer” has come to mean “lesbian, gay, and bisexual” in a spicier tone of voice.(1) This draining of political meaning from words we’ve called home has affected trans worlds less deeply than cis ones up to this point, but it is underway among us as well. The genealogy of “fem” as a trans word traces one strand of what that process aims to erase: an understanding of ourselves as directly dependent on each other to survive and flourish, as living and thriving through relation, solidarity, and endless variety and variation. “Fem” has named an aesthetic that makes that politics visible and recognizable, on our bodies and beyond them. It still can: if we pay attention to its roots, and cultivate what grows from them.

What Is This Thing Called “Fem”?

Words have meanings, and histories, and that’s why they matter. The words that trans people use about ourselves condense our understandings of the worlds we live in: we create and adapt them to do particular things. I want us to take the “fem” in “trans fem,” in this journal issue’s title “trans | fem | aesthetics,” seriously. To allow it all the layers of its histories. To know how and why it is a trans word, and to use it with its full weight. To not let it be diluted or defanged.

“Fem” comes to us from two worlds: the bars and the ballrooms.(2) Two worlds of working-class queers, outside the spaces made by and for the respectable people who used words for themselves like “invert,” “urning,” “homosexual,” “homophile,” “sapphic,” and, later, “gay,” “lesbian,” “bisexual.” Two worlds with their own ways of talking, their own words and meanings. Very different worlds, yet sharing a specific relationship to the categories that straights and respectable homosexuals live in and through, especially gender. Both built their own systems, their own categories, rejecting the idea that gender is internal, individual, an expression of an essence. The words used in both—“fem,” “butch”—trace that shared view of the world by naming positions that are not “woman” and “man,” not “feminine” and “masculine,” but specific other ways of being. Ways of being visibly queer. Ways of being recognizable to one another as people who will throw down for family, and whose safety depends on our siblings doing the same for us.

In the multiracial bar-dyke world of North America from World War I to the early 1970s, and then again in the early years of the butch/fem revival that began in the late 1980s, fem was not the opposite of butch.(3) Like butch, fem was the opposite of normative femininity and conventional womanhood.(4) Being a fem dyke meant being visible, standing out against the background of femininity and womanhood. It meant making yourself recognizable, so that if you need help, your people will know you, so that if they need help, they know you’ll have their backs. Fem style marks its bearer as noticeably identified with other queers.

On the other side of the line, being a “conventionally feminine” lesbian is blending in, going unnoticed. It means having enough money (and whiteness) that you don’t need other queers to have your back to survive. It means stepping out of the relationships of material care and mutual aid that come from being recognizably in the same boat, opting in and out of social cliques and community institutions as a separated individual. It means holding your identity within yourself, unnoticeable and internal, however much you call it your essential truth.

The one you notice in the picture—that’s the fem. She declines to do the little things that make a woman take up less space: suck in her belly, cross her legs, close her mouth, shave her armpits, keep her hands at her sides, eat less than her fill. Her style has something to do with sex workers—she might be one; if not, they drink together. It has something to do with cinematic divas—their implausibility, their excess. It has something to do with drag—at a minimum, the sex work and the movie stars. In any case, her style is no way for a proper woman to look, but it is adjustable for safety as needed. You notice her because she’s not a proper woman: she’s a fem.

The black and latinx(5) world of balls and houses, as it has existed in North America from the nineteenth century (at the latest) through the current period that began in the late 1960s, isn’t mine.(6) I’ll say a few words here to explain what I see flowing from the ballroom world into other trans uses of fem, and return to it here and there, within my limits of understanding (mostly gained by the usual queer methods of gossiping, eavesdropping, and ordering another drink). But I won’t claim to have the grounding to give a fully elaborated account.

In the ballroom world, Femme Queen is one position among many, one place to stand as a performer and as a person in the world. It has its own iconography, its own choreography, and “realness” is simply one skill cultivated among many. What matters most is relations: being a child of a house, a mother, a father (or a free agent among the houses); being acknowledged as a legend, an icon.

Femme Queen is a position that exists through its relations with other categories: Butch Queen, Woman, Butch, and others. But the defining contrast for Femme Queen, as I see it, is not with any of these categories. It is with a life lived stealth—blending in, walking away, and losing relation. An absence of connection to a house and its other children, to the constellation of houses as they come together in the ballrooms. Choosing to present yourself to the world as natural rather than as real. Attempting to dissolve into normative femininity and womanhood.

These two worlds—the bars and the ballrooms—came together in certain ways as the fem/butch revival and the ballroom world’s new visibility (after Vogue and Paris Is Burning) gradually rubbed up against each other. The phrase “hard femme” came out of that process in the 2000s, to name a specifically black and latina gendering at home in black queer nightlife spaces where ballroom children also set the tone (GHE20G0TH1K being an eventually high-profile example). In the often whiter and more overtly politicized spaces of the fem revival—where some younger white women simply used the word “fem” as a spicier label for their conventionally feminine “lipstick lesbian” mode—the torchbearers deliberately created gender-expansive and multiracial spaces, including folks from the ballroom world at times. Two key projects of that kind, the New York City–based Heels on Wheels collective and the Bay Area’s Femme Sharks, made explicit in their performances, manifestos, and interventions that they chose fem because it meant visible difference: in gender, in ability, in size, in race.(7)

In the bars and the ballrooms, it’s not just that fem dykes and Femme Queens hold a space separate from normative femininity and the womanhood it defines. Each world is based on an understanding that gender is something that happens between people, in relation, so the genderings that we use in our queer cultures depend on the ways that we cocreate each other. Fem, like any other queer gendering, is about identifying with, not as. Identifying with not only those who wear the same label, but with the landscape that gives that label meaning: a fem among fems, alongside other dykes (whether butch, kiki, stud, etc.); a Femme Queen among Femme Queens, within houses or as a free agent between them (alongside Butch Queens, Women, etc.). Those are the webs of relation that make us noticeable, that mean we can recognize each other. And we need to recognize each other because we rely on each other.(8)

trans | aesthetics

These two worlds, the bars and the ballrooms, connect directly to trans worlds, and in particular the worlds made by trans people in motion away from manhood.(9) In the ballroom world, that means most (if not all) Femme Queens; in the bars, that has meant (in different times and places) both those acknowledged as dykes and others present as fellow sex workers or as drag performers. But even beyond those directly involved in these subcultural spaces, many trans people in motion away from manhood have understood fem as a key reference point for understanding the practice of our lives. For as long as there has been an organized trans liberation movement in North America, fem has been used to define a set of trans aesthetic and political approaches that resonate with the word’s history in the ballrooms and bars.

That resonance is built on the concrete reality that the worlds we have made for ourselves have been structured by the same divide that gives fem its meaning. Some have complied with doctors’ orders and set their sights on normative femininity and womanhood, aiming to disappear as trans people and hoping a community of shared experience would not be necessary to their survival. Others—following the path of fem, not femininity—insist on remaining recognizable to each other and ourselves, rejecting cis aesthetics in and on our bodies, and relying on each other to survive and thrive.

In the first generation of specifically trans organizations in North America, just after the wave of queer uprisings that crested at the Stonewall in 1969, the Radicalqueens were the most explicit about this approach. In 1973, their Manifesto #2 declared: “We do not accept the traditional role of women as any alternative to the oppressor role of the male.” The term they used to mark the role they did embrace (in Manifesto #1, earlier the same year), was “femme-identified.”(10) They were not outliers. Even the names of the three organizations who drafted the 1970 “Transvestite and Transsexual Liberation” statement make that clear: Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), The Transvestite-Transsexual Action Organization (TAO), and Fems Against Sexism.(11) The first two names, like the title of the declaration, announce a specific rejection of the basis of a stealth approach, committing to mutual support rather than endorsing a division between those who do and don’t pursue medical transition, those who do and don’t identify with the category of woman, those who do and don’t get read as cis by a hostile world. That same division is enshrined in all the variations of terminology that have recreated the “transvestite”/”transsexual” split during the past fifty years; rejecting it is the basis of any meaningful trans organizing. In the words of the “Transvestite and Transsexual Liberation” statement: “Trans Lib includes transvestites, transsexuals and hermaphrodites of any sexual manifestation and of all sexes.” And the name of Fems Against Sexism makes explicit where that position of trans unity against normative visions of gender sees itself reflected: in fem.

In the next great upsurge of organizing and cultural work by and for North American trans people, in the 1990s, that approach got even louder. In the new wave of direct action, agitation, and organizing, the “menace” in Transsexual Menace (the most visible trans organization of the period) was the threat of noticeability, of refusing to be stealth, of rejecting the aspiration to model ourselves on cis bodies and lives.(12) Trans cultural workers showed what that meant in practice, modeling a trans-centered aesthetic of recognizability as a practice of mutual support and solidarity, both in spaces that could be called home (however temporarily and tenuously) and in actively hostile environments.

The examples that follow are glimpses of common practices and understandings, made visible by cultural workers and organizers who made them explicit in their work, and whose work has survived or left traces still legible after three decades.

The first issue of gendertrash (dated April–May 1993)(13) begins with a piece called “welcome,” in which editor Xanthra Phillippa declares

our […] need to be valid on our own terms

to express ourselves in our own languages

phrases

words

ways

to feel strong being ourselves

to be heard by ourselves

for community

to be who we are

to control our own futures

our own lives

our own bodies

to develop our own gender culture […]to explore our […] bodies

free from gender expressive controls

limits

This emphasis on refusing cis models for life, language, and embodiment permeates every issue of gendertrash, as it looked towards

a world that is not owned by one

a few

a world that is shared by all of us

a world of our own

—and modeled what that world could look like in its pages.

Elsewhere in the first issue, Phillippa made it clear that she and her coconspirators did not see blending into normative womanhood as a desirable goal. “Passing,” she wrote, “is something you do to protect yourself when: / >> the genetics are coming to kill you / because you are gender described / […] In fact, passing is a nightmare.” The distinctive terminology she uses here and elsewhere was part of an effort to “develop our own language & impose it on this gender suppressive society” rather than submerge an autonomous, recognizable trans culture. She proposed using “in the pit (instead of coming out of the closet for lesbians and gays),” “metamorphosis (instead of the clinical term transition),” and “in/into the woodwork” for “how some of us, usually anonymously, try & fit into this genetic mainstream society.”

The phrase “in the woodwork” has no opposite in Phillippa’s list of “TS Words & Phrases.” In a language that is for us and by us, living a life that is not “anonymous” or hidden—a life that is based on being recognizable, being known to each other—is simply living. Like the earlier wave of trans organizers, Phillippa looked back to fem/butch bar culture as a precedent for this way of moving through the world. Being herself a “TS Butch” (as she wrote in gendertrash #3), she made that connection visible by defining a difference between “transsexual lesbians” and “transsexual dykes,” using the overall term for the working-class queer rejection of normative womanhood, “dyke,” rather than the subcategory “fem.” In her glossary, “transsexual lesbians” are those who are primarily attracted to cis women, while “transsexual dykes” are primarily attracted to other trans women. Neither position is presented as an exclusive desire; the distinction is whether someone’s main sexual mode draws them closer to or further from a life in the woodwork.(14) What matters is living “on our own terms” rather than through cis standards and approaches, so that we can “feel strong being ourselves” and “control our own futures.”

A few months after gendertrash debuted, and on the other side of the continent, the same vision took the stage in a very different context, in front of a cis audience. When Susan Stryker first showed the world her (now acclaimed) praise-song to transgender rage, “My Words to Victor Frankenstein Above the Village of Chamounix,” the piece was not an essay. Although it was presented at an academic conference, it was a performance text, in which she aimed “to perform self-consciously a queer gender rather than simply talk about it” and “express a transgender aesthetic” with both her words and her physical presence. As she describes it:

I stood at the podium wearing genderfuck drag—combat boots, threadbare Levi 501s over a black lace body suit, a shredded Transgender Nation T-shirt with the neck and sleeves cut out, a pink triangle, quartz crystal pendant, grunge metal jewelry, and a six-inch long marlin hook dangling around my neck on a length of heavy stainless steel chain. I decorated the set by draping my black leather biker jacket over my chair at the panelists’ table. The jacket had handcuffs on the left shoulder, rainbow freedom rings on the right side lacings, and Queer Nation-style stickers reading SEX CHANGE, DYKE, and FUCK YOUR TRANSPHOBIA plastered on the back.(15)

This is not how normative femininity shows up for a panel. It’s not the womanhood that the doctors whose gatekeeping Stryker survived intended for her to enact. It’s not simply out of line with academic norms; it’s so excessive that it doesn’t even acknowledge the boundaries it’s crossed in its “disidentification with compulsorily assigned subject positions.” It insists on offering a different possibility to the world, on letting others know that even after going through a medical process explicitly designed to normalize trans bodies, “we transsexuals are something more, and something other, than the creatures our makers intended us to be.” The “we” is a broad one, but also precise: we who offer ourselves as visible to each other.

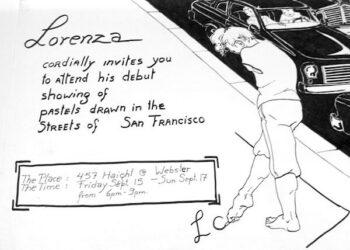

Stryker’s embrace of the monstrousness ascribed to the bodies of trans women who refuse normative femininity rhymes with the work of Lorenza Böttner, whose visual art and performances placed her armless trans body in a lineage of “freaks” and supposedly unnatural or broken embodiments.(16) As she moved among disciplines and genres (and invented new ones) from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, Böttner refused to normalize herself in terms of gender or ability. She declined to use prosthetic arms of any sort and placed her painting and drawing techniques using her feet and mouth at the center of the “danced painting” form that she developed for performances in public spaces and depicted on publicity cards for her shows.

Lorenza Böttner, untitled, 1985. Pastel on paper. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy of the Art Museum at the University of Toronto.

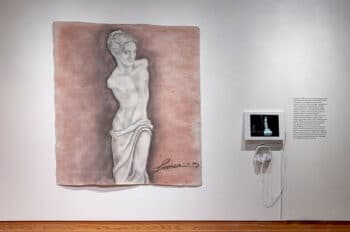

Similarly, she portrayed herself in a wide range of genderings in all the media she worked in, maintaining her recognizability as trans even in static gallery presentations of her visual work. And she used that refusal of cis and ableist standards as an explicit theme. In performances during the 1980s, she appeared as the Venus de Milo on a mobile pedestal, presenting her doubly deviant body as the image of classical beauty, and then descended to dance, asking the audience: “What would you think if art came to life?” Rather than allowing herself to be absorbed, in the audience’s eyes, into the normative beauty of the statue’s silent marble, she brought the everydayness of her particular body into direct relation with the audience as a speaking, moving person acting on her own terms.(17)

Böttner’s refusal to put either the trans or the disablized aspects of her body into the woodwork, and her insistence on making both fully present and recognizable throughout her work, is itself an analysis of the interwoven nature of the eugenic project that targets both ways of being. Her armlessness, though the result of an accident, placed her in a category of eugenic inferiors who should not be permitted to have children, according to the scientific, scholarly, and policy consensus promoted throughout Europe, North America, and the colonized world. Her trans life, despite the ostentatiously socially constructed nature of all the world’s varied gender systems (including the Christian Roman one that colonialism has made dominant worldwide), also made her a target for eugenic suppression of reproduction. Her 1980 self-portrait as a mother feeding her child is a subtle but forceful condensation of resistance to both of these faces of eugenics.

Lorenza Böttner, untitled, 1985. Pastel on paper. Private collection. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy of the Art Museum at the University of Toronto.

Böttner’s pastel self-portrait echoes classical Madonna-and-child compositions: she is nude, cradling the infant in a white cloth, looking past it towards the viewer as her loose hair falls around her shoulders. But it insists on the specificity of all the elements that the eugenic imaginary would use to justify her sterilization or loss of parental rights: the baby is held in the crook of her knee and its bottle between her shoulder and ear; her strong jaw, flat chest, and armless shoulder sit at the center of the image. Whatever the piece says about Böttner’s personal relationship to motherhood (no source I’ve found gives any indication), it is an uncompromising rejection of the eugenic ideology that has determined the structural and institutional place of trans and disablized lives for more than a century. More than that, it poses itself against both the disablized and the trans responses to that ideology that seek safety in blending in, in becoming unnoticeable, in aspiring to the coerced norm.(18)

Just over twenty years later, Mirha-Soliel Ross (the other editor/publisher/writer behind gendertrash) began her nine-month performance, The Pregnancy Project. Between May 2001 and February 2002, she only appeared in public pregnant (at times with a stroller), documenting the piece in two films, Allo! Performance and Lullaby. Her aim, as publicity for Allo! Performance put it, was “to explore transsexual women’s relationship to the personal and institutional aspects of motherhood and to arouse community discussion around the ethical and political implications of controversial reproductive technologies and prospects.”(19)

Lying behind that, as it was for Böttner’s self-portrait, is the eugenic context of trans life. For Ross, that is amplified by her family’s history as survivors of attempted genocides and longstanding eugenic extermination projects, both in her Métis (indigenous peoples now mainly living under Canadian rule) lineage and her Bnei Anusim (forced Christian convert) Jewish lineage. As she puts it: “At the end of the video I fall in the water, I collapse, I fail in the water, to be a woman who can reproduce, can reproduce either Jewishness or Aboriginalness, on foreign territory.”(20)

Ross’s answer to eugenic targeting and to the natalist imperatives of genocide survivor communities is not to evade complex questions by disappearing her trans life. Instead, she heads directly for their hardest parts, making herself fully visible through her public performance of trans pregnancy and, through the conversation with her mother that provides the soundtrack for Allo! Performance, actively drawing out the entanglements with class, family history, and lineage that could have remained hidden. In discussing the film, Ross made it clear that its visual style was intended to tie it to feminist critiques of normative womanhood and femininity as concentrated in the institution of motherhood, through both an overall visual “reference to documentation of early feminist performance art” and a specific allusion to Shulamith Firestone in her outfit.(21)

Mirha-Soliel Ross brought a similarly layered understanding of what developing trans culture “on our own terms” would mean to another collaboration with Xanthra Phillippa, beginning in 1997. The festival of trans film and performance they founded, Counting Past Two, deliberately aimed to break the tendency to present trans work that “comes from a very narrow scope in terms of diversity” and to show work that is not “necessarily about transsexual/transgender issues … [but] that’s made by transsexual artists.” The festival’s commitment “to look at other things that make people marginalized” beyond being trans explicitly guided its aesthetic vision.(22) Ross and Phillippa encouraged those without the resources (or the desire) for “fancy editing” (for instance) to make work so that it could be placed alongside that of established cultural workers like Aiyanna Maracle, whose self-description as “a Mohawk transformed woman who loves women” marked a refusal to be absorbed into either the dominant colonial culture or the terminology of its trans subculture. One of many ways to understand the name “Counting Past Two” is as a way of highlighting the interweavings the festival encouraged, all of which strengthened the trans aesthetic it cultivated.(23)

This constellation of trans women’s cultural work is brought together by a liberationist aesthetic of recognizability as solidarity. Some of its creators follow Radicalqueens in explicitly tying that back to “fem” and its bar and ballroom origins; others do not. But the trans worlds that all of them address and call into being are defined not by an internal, inherent identity but by a shared way of being in the world on our own terms: the approach that “fem” names. These particular trans permutations of the fem approach are themselves traceable because their status as art, as publications, has preserved them, so that they could be unearthed by the excavations of our history over the past decade. There are many more examples from more everyday contexts that go unrecorded. The trans dyke who joins a drag king troupe and sings Johnny Cash numbers in the original key because she can. The thirty- and forty-year-old trans women who notice a freshly hatched sister arrive at a theater project’s launch party and chuckle together about how their stubble is modeling resistance to online tutorials on how to be stealth. The sex workers who recreated the “transsexual dykes”/”transsexual lesbians” (and “transexual fags”/”transsexual gays”) distinction as they invented “t4t” to tag their off-the-job hookup ads on Craigslist. The thrift-store and clothing-swap aficionados who scoop up garments designed in ways that make them unfit for the actual bodies of almost all the cis women they are supposedly made for.

All these ways (and more) of celebrating the specific recognizability of our own voices, our own faces, our own language, our own bodies are enactments of the trans aesthetic that rejects living stealth, refuses to embrace cis standards of how to be a body in the world, declines to blend into normative womanhood and femininity, and insists that our survival depends on mutual support and solidarity. Declarations that our style is our armor because it signals solidarity offered and desired. Elements of a way of being that we have named over and over as “fem.”

A Restricted Country

The gaps in the histories I’ve been weaving together, of lineages of fem united by a shared vision of gendering as a collective process of refusing to live in the woodwork, are not accidental, or the simple result of the passage of time. Fem as a way of being in the world has been deliberately attacked over and over again, in each case by people claiming to be the better, truer, purer fighters for freedom. These attacks have targeted fems and other working-class bar dykes, Femme Queens and other ballroom children, trans women and other trans and nonbinary people—often all at once.

In the 1970s, a faction calling itself “radical feminist” became dominant in the (largely white) North American lesbian feminist world, reshaping that world around biological essentialism.(24) The purge of trans women from lesbian feminist spaces under this new orthodoxy was inextricable from the purge of fems and butches, and the purge of sex workers and leatherdykes. Longtime trans leaders in lesbian institutions like Beth Elliott (of the Daughters of Bilitis) and Sandy Stone (of Olivia Records) were pushed out, along with working-class cis fems like Joan Nestle, Amber Hollibaugh, and Minnie Bruce Pratt.(25) They were all condemned for living outside the bounds of “true and natural” womanhood.(26) The consequences of the purge did differ. Only a few of the expelled trans women were able to maintain substantial connections to lesbian and feminist spaces during the 1980s and ’90s.(27) The targeted cis women, on the other hand, retained more access, which many of them used over the next few decades to recapture space for all those targeted by the purges, including both fem/butch dykes and trans women.(28) Their solidarity was part of what made possible the slow (and still incomplete) shift we’ve seen since the 1990s in feminist movements and lesbian spaces towards support for trans women and sex workers.

Successive waves of respectability politics have played the same role in relation to Femme Queens throughout the past century. Even when other forms of black and latinx queer life in the U.S. have gone comparatively uncontested, the inherent visibility of ballroom culture and its strong appeal to people outside its houses have made it a favored target for many black liberals and radicals. To give an early example: after a benefit ball at Harlem’s Renaissance Casino in the late 1920s, supporting the Fort Valley Industrial School for Colored Children, an editorial in a black newspaper attacked the “disgraceful antics of the nude women and female men” who attended “by the scores.” The writer was very explicit: the school’s task of racial uplift, “the making of manly men and womanly women,” was undermined by an event where “colored graduates of northern Universities” could mingle with the “abnormal” rather than “lift … their race in the respect and confidence of the Caucasian world.”(29)

This attitude, essentially unchanged, can be seen down to today, when ballroom children are visible in popular culture (through cis-led shows like Pose, for instance) but find minimal material support for their needs from the NGO sector and other respectable progressive institutions. These organizations are happy to use the images of murdered Femme Queens like Venus Xtravaganza or her younger sister Layleen Cubilette-Polanco Xtravaganza in their fundraising and media materials—but only because in death they are no longer unnaturally, criminally bad for the image of the race, of the movement. Their images, unlike their living presence, can be used to justify collaboration with the very institutions that killed them.(30)

Advertisements for Harlem balls and headline of article attacking the balls. Clippings in Carl Van Vechten scrapbook #10, Beineke Library, Yale University. Photo by the author.

During the current “tipping point” era, we’ve seen a new trans liberalism emerge into the role modeled by these earlier attacks, presenting itself as the new, improved path forward to freedom. It’s rather novel: almost no trans people have felt secure enough in their money (and whiteness) to embrace liberalism before! Until recently, even the most active advocates for a stealth life have acknowledged that theirs is an approach that can only work for isolated individuals, and that any collective liberation for trans people can only come through societal transformation. The new trans liberalism, however, promises freedom through conformity. It embraces the quest to blend into the cis world, retaining nothing but the word “trans” as the label for an internal, essentialized, individualized identity—ideally expressed while looking as indistinguishable from cis femininity as possible. The dream it offers is of an unnoticeable life, in which being trans is a private matter, allowing you to opt in or out of trans social circles, organizations, and institutions at will, with no lasting obligations to those you meet there.

In its most obvious forms, this new trans liberalism advocates, quite literally, for the building of new “gender-responsive” prisons to cage us correctly, rather than for our freedom.(31) This, like the divisions it encourages between woman-identified and nonbinary folks, between those who do and don’t want to use medical paths for metamorphosis, between those with and without access to the resources (monetary and social) necessary to access quality healthcare, is easy to see and to oppose. Less so are the more pervasive and subtle versions of the same principle, the ones more directly if less ostentatiously rooted in the eugenic imaginary that the trans practices of the “fem” approach I’ve been describing oppose.

The eugenic vision of the invisible transsexual sits at the heart of the new trans liberalism. At heart, this liberal project believes that the solution to being treated as deviant bodies is not to change the society that treats us that way, but to “correct” our bodies and lives away from deviance. The eugenic vision manifests itself in myriad ways: some ostentatiously aesthetic, some overtly political, and all (like the fem approach it opposes) with implications showing how these categories intertwine. It pushes for “reformed” gatekeeping over the gender markers on state identification, rather than removing markers and ending the gatekeeping. It tells us to embrace hatred of our bodies—whether due to gender, size, or white-supremacist beauty standards—as a marker of achieving normative womanhood, rather than participate in struggles against a misogynist society. It encourages us to spend money on learning to restrict ourselves to a stereotyped “female” vocal pitch, both ignoring the actual variety of women’s vocal ranges and constricting our own expressive voices. And perhaps most egregiously, it has worked to dismantle decades of successful work addressing kids’ gender expression.

We all know that not all trans adults dissented from their assigned genders as children. And we all know that not all children who do will become trans adults. This matters even more in practical terms than it does as one of many demonstrations that being trans is not an inborn essence; it shows that caring for trans people of all ages means prying schools and families and neighborhoods open to welcoming the full range of possibilities for being in the world, for every kid.

In the late 1990s, this understanding guided the creation of trans-affirmative clinics for kids, based on a feminist and queer approach that treated hatred of trans folks as the problem to be solved, not our bodies and minds. The first such clinic grew out of a Washington, DC, support group cofounded by Catherine Tuerk, a nurse whose child survived a “reparative therapy” clinic.(32) These trans-affirmative clinics focused on defusing parents’ toxic responses to kids who rejected their gender assignments, on dealing with the stigma and anxiety that a trans-hating society causes, and on supporting kids and parents in navigating and changing hostile institutions. They aimed at reducing kids’ pain and distress by any effective means (including access to the full range of medical approaches when that was part of a specific kid’s desires), while recognizing that no change to an individual trans person can eliminate pain, distress, and exposure to harm without structural social transformation. They were better at reducing that pain and distress than anyone else, and they (along with the 1990s wave of trans liberation organizing) pushed the previously dominant “reparative therapy” model into disrepute in only a few years.(33)

This mode of clinic has been actively marginalized over the past decade. It has been replaced, with the vocal support of many trans people, by gatekeeping institutions that exist to determine whether kids have the trans essence required to be worthy of the limited range of medical support these clinics provide. Kids are constantly scrutinized and assessed for what underwear they choose for a day when they have an appointment, for their adherence to stereotyped recreation preferences, for the haircuts they want, any of which can get them declared to be deluded about what they want, “externally motivated,” or just too gay to be trans.(34) If they make it through this gauntlet, the doctors’ goal for them is “a much more ‘normal’ and satisfactory appearance,” rather than a life with less pain and distress.(35)

The doctors who run these new clinics refer patients back and forth to the “reparative therapy” quacks, based on whether they think a child should be normalized into the gender the kid was assigned or into the single alternative option they allow.(36) And, building on their eugenic consensus, the trans clinic and reparative therapy doctors coauthor medical papers on supposed biological markers for inherent, genetic trans essences, and textbook chapters establishing “standards of care.”(37) These clinics, the most blatant incarnation of a eugenic approach to kids and gender, are what the new trans liberalism hails as a giant step forward.(38)

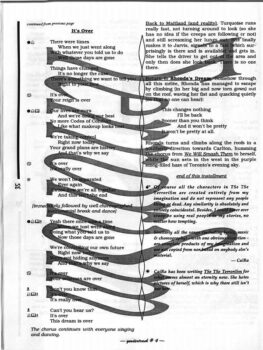

Last installment of CaiRa’s serial TSe TSe TerroriSm in the fourth issue of Gendertrash from Hell (1995). Photo by the author.

The new trans liberalism presents itself as an improved, “pragmatic” continuation of earlier trans organizing and cultural work. But, just like the essentialist lesbian feminism that claimed to transcend the fem/butch bar dyke world, and the respectable reformers who wanted to “uplift” ballroom life out of existence, it undermines and destroys what came before, and replaces it with precisely what that earlier work rejected. Its vision of living stealth in all but name, of “trans” as an individualized, internal, innate quality, is a refusal of the recognizability that enables mutual support, and of the interdependence that makes solidarity possible.

My Body Knows the Taste of Freedom Now(39)

So where is the fem lineage of trans life on our own terms right now? Where is a trans | fem | aesthetics that is built on this history, in which fem carries the meanings that have given it beauty and power for us?

As always, fem is most tangible in the inconvenient places, with the inconvenient people. Held by projects and people that the spotlight may occasionally touch, but who rarely hold the economic and social capital that it prefers to linger on. Projects and people that don’t do “trans” in isolation, but always connect it to other axes of power, other sites of resistance, other ways of being in the world. Projects and people that not only reject the dream of blending in, the lure of life in the woodwork, but also the double-edged fantasy of visibility, the trap of representation as an aim in itself.

Here are a few examples of current trans women cultural workers who take this approach, chosen mainly because I happen to enjoy their work and find it powerful. They’re weighted towards the urban spaces of the so-called Northeast, because that’s where I’ve lived. There are similar projects and people across the continent, and beyond its boundaries, and myriad everyday practices that embody the same way of being.

The cycle of writing and (anti-)publishing projects that Jamie Berrout has anchored or been involved in over the past five years have probably made available writing by more trans women of color than all other North American publishers combined (and possibly all other publishers worldwide)—and have certainly paid more trans women of color for their work.(40) Berrout and her collaborators have shown what can come from an active decision to do literary work on our own terms. They make work that both takes beautiful physical form and is freely available for digital distribution, to ensure that it can reach everyone they write from, and for. The anti-capitalist vision behind these projects is explicit, as is their goal of aiding collective liberation from white supremacy within trans spaces and beyond them. The two together feed a critique of publishing as an industry (including at the “artisanal” scale), and a call for a transformed relationship of writers and readers to cultural production.

Kama La Mackerel, as host of the long-running GENDERB(L)ENDER cabaret, and a convener of community-based mentorship and performance programs, has cultivated a range of spaces for trans and queer cultural workers of color in tio’tia:ke/Montréal and beyond. Their own performance and visual art explores ways of healing from colonial pasts and ancestral losses, embodying an “i” that “refuses to be restricted by singularity,”(41) and above all, affirming trans, black, migrant life. Much of that work is rooted in extended multidisciplinary research projects like From Thick Skin to Femme Armour. Kama La Mackerel’s first book (and the performance piece that shares its title and uses its text), Zom-Fam, takes its name from the language and gendering specific to their birthplace, Mauritius. Like much of their work, it dances in the spaces that connect and separate their specific lineage to other trans and queer histories and contexts.

Kama La Mackerel, For my Sisters, From Thick Skin to Femme Armour, 2017. Installation view at McGill University. Photo: Võ Thiên Việt.

Trans embodiments on our own terms find encouragement to resist the borders of nation-states and the colonial histories behind them on the dancefloors that DJ Precolumbian creates. Her work aims to extend the role of the DJ to deliberately use the party space as a site of collective healing, in opposition to “the enormous falsehood of safety, of refuge, of sanctuary the homes of empire offer.”(42) Precolumbian’s music, whether at a club, a house party, or her Radio Estregeno show, is both an invitation to and an assertion of a trans aesthetic that can’t exist in isolation.

Similarly, Elysia Crampton Chuquimia’s music has evolved to weave more and more elements of her Aymara lineage, sonically, politically, and philosophically, into her compositions and mixes. Her work moves between geographies, anchoring projects in the Shenandoahs as well as the Andes, and between times, looking to eighteenth-century Aymara revolutionary Bartolina Sisa alongside twenty-first-century U.S. abolitionist feminism. Like DJ Sprinkles / Terre Thaemlitz and other earlier trans dancefloor radicals, Crampton Chuquimia and DJ Precolumbian do not separate their cultural work from the organizing and mutual support that sustain us in a world that does not want us to survive—and that works a lot harder to eliminate some of us than others.

The history of black trans women surviving and finding joy despite state and social violence has been at the heart of Tourmaline’s film work. Her Happy Birthday, Marsha (with Sasha Wortzel, 2018), The Atlantic Is a Sea of Bones (2017), The Personal Things (2016), and Salacia (2019) invoke the full four hundred years of black life in North America, and the presence of that entire history as a past that remains tangible and live. Salacia’s portrait of Mary Jones—black trans sex worker and media sensation of 1830s and ’40s New York City—for instance, insists on the everydayness of Jones’s life, rejecting the sensationalizing depictions that circulated in her lifetime and reappear in current academic and popular references to her story. Tourmaline’s films evade the formal demands placed on “proper” narrative film, never allowing naturalism to get in the way of the real.

All these cultural workers take different paths, in the form and the content of their work as much as in the varied media they focus on. What they share is the fem in trans | fem | aesthetics: living through recognizability and relation, through mutual dependence and solidarity, through identifying with, not as. Each model’s cultural work addresses our varied lives using our own terms, in relation to the cultural workers and organizers who’ve come before us.

Trans worlds can only exist through affinity and active affiliation, so it is easy for us to become disconnected from even the histories of the words we use about ourselves. What we lose when that happens is the ability to cultivate lives that learn from each other, that aren’t imprisoned within a fantasy that perfection comes from newness and lack of roots. That is the fantasy that leads to reproducing boundary-policing battles from decades past, to embracing eugenicist gatekeepers as allies and saviors, to “gender-responsive” prison cells. We know our lives depend on each other; that we can only flourish in and through relation, in each moment and across time. “Fem” has been a word that helps us to hold that knowledge—and if we use it thoughtfully, it can continue to be.

×

Much of this piece comes out of innumerable conversations over the past twenty-five years with friends, comrades, lovers, and acquaintances; thanks go to all of them, and in particular Alexis Dinno, Sahar Sadjadi, Bryn Kelly zts”l, Emma Deboncoeur zts”l, Erin Houdini, Lenny O, Malcolm Rehberger, Margaux Kay, Milo, Roo Khan, Aleza Summit, Nina Callaway, and Trish Salah. We cannot live without our lives, or without each other.

Notes:

- For a powerful articulation of the political project “queer” was cultivated within, and an equally powerful critique of how queer political practice has often fallen short, see Cathy Cohen’s classic “Bulldaggers, Punks, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?,” GLQ 3, no. 4 (1997)

- I use the spelling “fem” as the general term and for the dyke world, following Joan Nestle’s account of bar dyke usage, where the frenchified spelling was considered pretentious. I use “femme” when I’m talking about the ballroom world, which consistently prefers it.

- The classics on fem/butch: The Persistent Desire: A Femme/Butch Reader, ed. Joan Nestle (anthology); Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community by Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline D. Davis (oral history—excerpt at →); Stone Butch Blues by Leslie Feinberg (fiction—available at →), A Restricted Country by Joan Nestle (fiction and biomythography).

- This is explicit throughout the writing on dyke life that exploded after the fem/butch revival began, much of which had to repeatedly explain why butch and fem were not simply versions of straight gender roles. I’ll quote one example of a rhetorical contrast between fem and normative femininity: a Women’s Monthly blurb from the Alyson Publications ad in the back of my 1996 edition of Pat Califia’s Doc and Fluff. It reads: “Images of so-called ‘lipstick lesbians’ have become the darlings of the popular media of late. The Femme Mystique brings together a broad range of work in which ‘real’ lesbians who self-identify as femmes speak for themselves about what it means to be a femme today.”

- I follow the tradition of black radicals (and their comrades) who do not capitalize the names of racial/ethnic/national categories, as a small refusal to give these categories undue power and attribute “objective reality” to them.

- Some sources by participants: Michael Roberson’s work with the Ballroom Freedom School (→) and elsewhere (for example: →); Marlon M. Bailey’s “Gender/Racial Realness: Theorizing the Gender System in Ballroom Culture,” Feminist Studies 37, no. 2 (2011), “Engendering Space: Ballroom Culture and the Spatial Practice of Possibility in Detroit,” Gender, Place & Culture 21, no. 4 (2014), and more; and Jonathan David Jackson’s “The Social World of Voguing,” Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movement 12, no. 2 (2002).

- For Heels on Wheels, see their 2015 anthology, Glitter and Grit; for Femme Sharks, see →. Key to both, and to the fem/butch revival generally, are fat feminist and disability justice organizing—both in explicit opposition to normative (and highly racialized) notions of femininity.

- The ideas about the importance of relation throughout this piece are tied to indigenous thinking about (right) relation, kin-making, and survivance, which can be found in work by (among many others) Qwo-Li Driskill, Audra Simpson, Kim Tallbear, and Métis In Space.

- I use this somewhat clunky phrase because we don’t have simple, materially grounded language yet to refer to the range of overlapping social positions, lived experiences, and relations to structural power among the people who are the central subjects of this piece. The most common terms all depend (directly or indirectly) on centering the gender a person is assigned at birth by doctors or parents in collaboration with the state (“AMAB,” “originally male-assigned,” and their synonyms), on collapsing all of us into a binary and normative gender category (whether womanhood—“trans women”—or femininity—“trans femmes” as the phrase is generally used), or on both these moves (“MTF,” “women of trans experience,” etc.). My phrasing above reflects the concrete and materially meaningful distinction among trans and nonbinary people, as I see it: our direction of motion in relation to the pole of binary gender that holds structural and institutional power. It is parallel to “transmisogyny affected,” but focuses on the structural relationship rather than the enforcement mechanism. Practically, from here on, I’ll mostly use “trans women” as an umbrella term, in the expansive sense that has emerged over the last ten years, which includes both binary-oriented and nonbinary folks in motion away from manhood, with our wide array of relationships to the category of “woman.”

- The two manifestos, and an essay on Radicalqueens by cofounder Cei Bell, are republished in Smash the Church, Smash the State: The Early Years of Gay Liberation, edited by Tommi Avicola Mecca (the other cofounder of Radicalqueens). The manifestos are online at →.

- The Transvestite and Transsexual Liberation statement was reprinted in Susan Stryker’s Transgender History, and is included in the same online anthology as the Radicalqueens manifestos.

- Transsexual Menace was a trans counterpart to Queer Nation: a mid-1990s network of several dozen groups across the U.S. that came together as needed for zaps and other (mainly media-oriented) actions targeting anti-trans organizations and events, and at times for other education and agitation work. Its T-shirts and stickers in the Rocky Horror Picture Show title font were a major part of politicized trans visibility for many years.

- All four issues of gendertrash can be found online (along with other material related to the magazine) at →.

- It’s important to note that thinking about trans folks who aren’t straight is central to any thinking about trans people, not a margins-of-the-margins question. The best demographic information we have on trans people in the U.S. (from the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey and the 2008–09 National Transgender Discrimination Survey) shows that an overwhelming majority of us are not heterosexual: in the nonexclusive categories used in the USTS, 81 percent of trans women and 98 percent of nonbinary folks. A near-majority of trans women (including folks who are also nonbinary/genderqueer/agender/etc.) consider themselves queer, bisexual, or pansexual; another quarter use gay, lesbian, or same-gender-loving. The surveys’ methodology may be shaky—they asked about identity terms, not sexual or romantic partners’ genders—but the conclusion is not at all uncertain. Perhaps marking a certain discomfort with its own results, the report does not break down the 11 percent of its respondents who identified themselves as lesbians into its overall categories of trans women, trans men, and nonbinary folks (though the survey data would allow that to be done); its methodology definitively prevents us from distinguishing between trans dykes and trans lesbians.

- All the text from “My Words …” is quoted from the version of the text published in Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle’s The Transgender Studies Reader.

- This embrace of monstrosity has been a continuing theme in trans fem and trans feminist aesthetics. A key example from midway between Stryker’s piece and the present is “the seam of skin and scales” by little light / Elena Rose Vera, available at → and printed in The Emergence of Trans: Cultures, Politics and Everyday Lives, ed. Ruth Pearce, Igi Moon, Kat Gupta, and Deborah Lynn Steinberg (Routledge, 2019).

- This performance description is based on the brochure essay written by Paul Preciado for the 2020 exhibit “Lorenza Böttner: Requiem for the Norm” at the University of Toronto Art Museum, which is available at →.

- I won’t try to dig into the interweavings of trans and disability politics beyond Böttner’s work, except to point out that what I’ve been describing all through this piece is the trans approach that’s parallel to the disability-justice framework, which has been developed (largely by queer and trans disablized folks) to directly address the shortcomings of the “social model” of disability that has guided advocacy and policy efforts for many years. See, for instance, Eli Clare’s writing (including Exile and Pride and Brilliant Imperfection), the work of Sins Invalid (→), and AJ Withers’s Disability Politics and Theory.

- Quoted in a Tumblr post by Morgan Page that includes a link to watch the film, at →.

- Quoted in curatorial notes for Tobaron Waxman’s “TOPOGRAPHIXX: Trans in the Landscape,” at →.

- Also from Tobaron Waxman’s curatorial note. The complicated relationship between Firestone’s writing and trans lives and trans feminist analysis is explored a bit here: →.

- This commitment is visible more broadly in the Canadian trans world of the 1990s, with Vivian Namaste holding similar space as an organizer, researcher, and writer. See her Invisible Lives: The Erasure of Transsexual and Transgendered People; Sex Change, Social Change: Reflections on Identity, Institutions, and Imperialism; andC’était du spectacle! L’histoire des artistes transsexuelles à Montréal, 1955–1985.

- All these quotations are from a 1999 radio interview with Mirha-Soleil Ross by Nancy Nangeroni, on the GenderTalk program, which is available (with a transcript) at →.

- For excellent contemporaneous critiques and analyses of this essentialism, see the “French Speaking Lesbian Consciousness” section in Sarah Lucia Hoagland and Julia Penelope’s For Lesbians Only: A Separatist Anthology.

- All of these folks have written on the purges, and the latter three on the “sex wars” that followed them within lesbian feminist spaces. I especially recommend Beth Elliott’s memoir, Mirrors, which depicts trans women’s lives in the pre-purge lesbian feminist movement (though I’ve heard it may be best to read her forward to the latest edition after the rest of the book).

- The forms of nominal androgyny that embodied this “authentic” womanhood may seem far less transgressive of conventional femininity now than they were at the time—but even then, jewish, black, and latina dykes pointed out how the prescribed norms of behavior and speech reproduced the conflict-avoidant, passive-aggressive style of normative WASP femininity (a tradition that has continued in the NGO sector, where those norms are now marketed and enforced, on trans women in particular, as “Non-Violent Communication”).

- Parts of the leather scene remained comparatively welcoming, though with a great deal of variation.

- One example: the Lesbian Herstory Archives, which Joan Nestle cofounded in the mid-1970s, has never excluded trans women, though how welcoming it has been in practice has varied through time.

- Clippings containing an ad for the ball, and the letter attacking it—neither one dated or marked with a source—appear on a page with an ad for a 1927 ball presented by the same promoter, Jimmy Harris, in volume 10 of Carl Van Vechten’s as-yet-unpublished scrapbooks of queer and trans material (held at Yale’s Beineke Library).

- As it has been by NGOs and elected officials invoking Layleen’s name as they advocate for jail expansion rather than an actual plan to close the Rikers Island jail that killed her. Similarly if more subtly, the provisions of reform efforts like the HALT Solitary legislation passed in 2021 (which does make some meaningful changes to New York State’s carceral system) would not in fact have prevented the torture through isolation that led to Layleen’s death. All this stands in contrast to grassroots groups led by and made up of trans folks of color, who have been heavily engaged in abolitionist work (many of them with direct ties to the ballroom world). Some NYC examples are the F2L Network (→) and GLITS (→).

- For a detailed analysis of this tendency, focused on New York City and State, see Survived & Punished NY’s report, “Preserving Punishment Power” →.

- See Edgardo Menvielle and Catherine Tuerk, “A Support Group for Parents of Gender Non-Conforming Boys,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41, no. 8 (2002).

- For more on trans-affirmative clinics, see Patricia Leigh Brown, “Supporting Boys or Girls When the Line Isn’t Clear,” New York Times, December 2, 2006 →; D. B. Hill et al., “An Affirmative Intervention for Families With Gender Variant Children: Parental Ratings of Child Mental Health and Gender,” Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 36, no. 1 (2010); and Edgardo Menvielle, Catherine Tuerk, and Ellen Perrin, “To the Beat of a Different Drummer: The Gender-Variant Child,” Contemporary Pediatrics 22, no. 2 (2005).

- See Sahar Sadjadi’s “Deep In the Brain: Identity and Authenticity in Pediatric Gender Transition,” one of very few publications based on extended on-site observation of clinic practices (both in interactions with children and families and—most importantly—among doctors in private), rather than relying on interviews and other forms of self-representation and publicity. It is available at →.

- Simona Giordano, “Lives in a Chiaroscuro: Should We Suspend the Puberty of Children with Gender Identity Disorder?,” Journal of Medical Ethics 34, no. 8 (2008).

- A physician-turned-researcher tells me that until Kenneth Zucker’s notorious “reparative therapy” clinic was finally closed down, he supplied so many patients to clinics specializing in puberty blockers that he was considered one of their biggest referrers and practical supporters. None of these clinics reported Zucker’s pattern of sexual assault on his patients.

- Coauthorship is the best sign of doctors’ and scientists’ own understanding of their affiliations and alliances; it marks an even closer relationship than citation (which Sara Ahmed has pointed to as key to any analysis of intellectual proximity and influence). In trans healthcare, lasting patterns of coauthorship clearly establish that doctors portrayed as representing opposing positions in fact see themselves as part of a shared project. Two of the highest-profile doctors whose work trans liberal authors like Julia Serano contrast (at times by name), Peggy Cohen-Kettenis (an acclaimed “pro-trans” puberty-blocker pioneer and stalwart of the World Professional Association of Transgender Health) and Kenneth Zucker (a notoriously “anti-trans” “reparative therapy” advocate) provide a perfect example. Cohen-Kettenis and Zucker have published together in many different contexts over decades, from authoritative textbook chapters like “Gender Identity Disorder in Children and Adolescents” (Handbook of Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders, 2012) to explorations of alleged correlations between trans identity and finger-length ratios (Wallien et al, “2D:4D Finger-Length Ratios in Children and Adults with Gender Identity Disorder,” Hormones and Behavior 60, no. 3, 2008) and sibling sex ratio (Blanchard et al, “Birth Order and Sibling Sex Ratio in Two Samples of Dutch Gender-Dysphoric Homosexual Males,” Archives of Sexual Behavior, no. 25, 1996). The other authors on these and their other papers include both Cohen-Kettnis’s colleagues from the “pro-trans” clinics and some of the doctors most notorious for their anti-trans positions, Ray Blanchard and J. Michael Bailey among them.

- For a brief examination of this history, in the context of the ongoing attacks on support for gender-dissenting kids and the temptation “to take the opposite position of one’s enemy,” see Sahar Sadjadi’s “The Vulnerable Child Protection Act and Transgender Children’s Health,” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 7, no. 3 (2020).

- This section’s title comes from “Sid’s Aria,” the turning point of Nomy Lamm’s 2000 rock opera, The Transfused.

- These include the fiction anthology Nameless Woman(edited by Berrout, Elly Peña, and Venus Selenite in 2016); the double-dozen issues of the Trans Women Writers Booklet Series that Berrout edited and designed (available at →); and the publications of the ongoing River Furnace writers collective (→). Alongside these projects, Berrout has released her own poetry, prose, and essays and her translations of Venezuelan poet Esdras Parra and Argentinian organizer Lohana Berkins. Much of her work can be found at →.

- See →.

- See →.