China surged past the United States to become the #1 carbon emitter in 2006. Currently (2019 data from BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy), its CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel burning are over 9,800 million metric tons (“tonnes”) a year. That is nearly double U.S. emissions for the same year, and a staggering 29 percent of total 2019 world CO2 emissions from burning coal, oil and gas. China’s 2019 emissions are nearly triple the level from 20 years earlier (3,294 million tonnes, also from the BP Review).

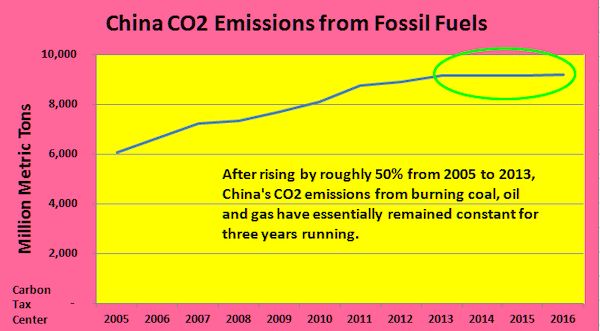

From 5 percent annual emissions growth to 2013, to a dead stop thereafter, is nothing short of remarkable.

This is a less upbeat picture than what we portrayed in our most recent post on China, Why China’s Emissions Triumph Surpasses the United States’?, from 2017. That post highlighted four grounds for optimism on China:

1. China’s carbon emissions were well under half of U.S. emissions on a per capita basis. U.S. per capita CO2 emissions of 15.4 metric tons in 2016 were nearly two-and-a-half times as great as China’s 6.4 tonnes per person in the same year, owing to the 4-to-1 population disparity.

2. Much of China’s CO2 come from fuel burning to manufacture goods exported to the United States. In 2017 those emissions far outstripped U.S. emissions to supply agricultural and other products to China. That’s still the case.

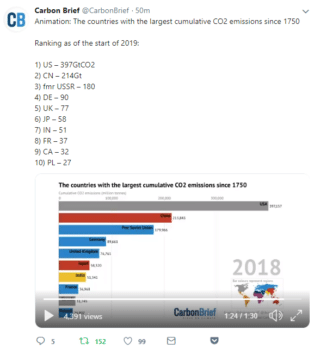

3. Based on historical CO2 emissions—which determine the amount of atmospheric carbon pollution now trapping Earth’s heat, given the roughly hundred-year time scale for a carbon dioxide molecule to disintegrate–U.S. climate-damage responsibility was then, and is still, almost double China’s, even without normalizing for population, as demonstrated in this simulation by Carbon Brief.

Cumulative U.S. emissions are nearly twice China’s, per Carbon Brief. (See text above, #3 paragraph, for link to CB’s tweet with actual animation.)

4. China’s CO2 emissions stayed roughly constant for four years, from 2013 to 2017, a sea-change in its previously inexorable rise in carbon pollution. From 2005 to 2013, China’s compound average emissions increase rate was 5.3 percent. To bring emissions to a screeching halt since then, without famine, pandemic or war appeared close to miraculous.

We wrote in 2017 that even though China accounted for roughly one-quarter of annual global emissions of carbon dioxide (now nearly 30 percent, as noted), there were grounds to view it as a leader in global climate progress, as some were doing then, in contrast to the U.S. government’s slavish embrace of fossil fuel extraction and willful abandonment of climate goals under President Trump. China itself appeared comfortable adopting that mantle, as evidenced by a March 2017 editorial in the state-run nationalist newspaper Global Times noting that “The Trump administration has become the first government of a major power to take opposite actions on the Paris Agreement. It is undermining the great cause of mankind trying to protect the earth.”

Unfortunately, China’s carbon emissions climbed sharply higher in 2018 and 2019, with annual increases of 2.2% and 3.3%, respectively, according to the BP data. Perhaps Trump climate arson played a part, directly through his administration’s trampling of the carbon detente between Presidents Obama and Xi Jinping and the Paris Agreement, and indirectly as U.S. fossil fuel valorization gave license to climate pollution around the world.

A 2020 Pledge for Carbon Neutrality–in 2060

In September 2020, President Xi pledged at the annual meeting of the United Nations General Assembly that China would adopt much stronger climate targets and achieve what he called “carbon neutrality before 2060,” the New York Times reported. The Times called it “China’s boldest promise yet on climate change,” while noting that President Xi’s announcement contained few details.

The timing of the announcement was notable, according to the Times, “coming so close to United States elections in which climate change has become increasingly important to voters,” and “demonstrates Xi’s consistent interest in leveraging the climate agenda for geopolitical purposes,” said Li Shuo, a China analyst for Greenpeace.

We will share details of China’s 2060 pledge, if any emerge.

The 2014 Policy Turnaround

The announcement in November 2014 of a U.S.-China agreement to curb greenhouse gas emissions was both a surprise and a milestone, shattering the “alliance of denial,” as the New York Times once termed it, by which the two nations used each other’s inaction as a pretext to postpone action on climate. The pact committed China, for the first time, to cap emissions of greenhouse gases, with the turnaround to come no later than 2030.

The announcement in November 2014 of a U.S.-China agreement to curb greenhouse gas emissions was both a surprise and a milestone, shattering the “alliance of denial,” as the New York Times once termed it, by which the two nations used each other’s inaction as a pretext to postpone action on climate. The pact committed China, for the first time, to cap emissions of greenhouse gases, with the turnaround to come no later than 2030.

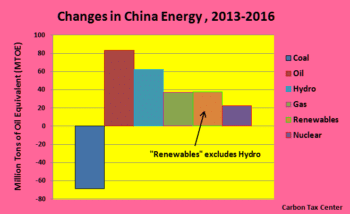

Around that time, reports began emerging that China’s coal consumption was plateauing and even declining, as suggested by the graphic further below, “Chinese CO2 Emissions to 2015.” An early and key source of this information was Greenpeace International’s coal campaigner, Lauri Myllyvirta. Apparent causes included a slowing of industrial output; addition of major hydro-electric and nuclear power capacity; displacement of coal-fired generation by gas, wind and solar; and increased energy efficiency. (Anyone interested in these developments should follow Myllyvirta on Twitter.)

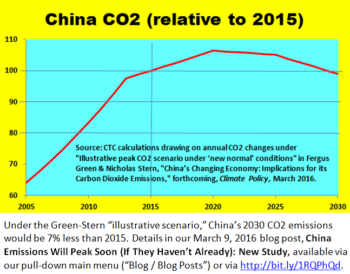

Even more strikingly, a paper published in March 2016 in Climate Policy forecasted that China’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion might peak as early as 2020–a full decade before the cap target year. Moreover, rather than shooting past earlier benchmarks, emissions in 2030 would be 7% below the 2020 peak and even 1% under 2016 emissions, according to the Climate Policy forecast. Such a turnaround would exceed all but the most buoyant expectations that greeted the 2014 announcement and would raise the bar for the U.S. and the other 190 nations that submitted emission pledges at the U.N. climate summit in Paris in December.

That upbeat analysis came from two of the world’s most prestigious climate think tanks: the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, both based in London. The authors were Fergus Green, a climate policy consultant from the London School of Economics; and Sir Nicholas Stern, director of the Grantham Institute and arguably the world’s most renowned climate economist. (We reported on their analysis in a March 9 blog post, China Emissions Will Peak Soon (If They Haven’t Already): New Study.)

Indeed, China’s cap pledge virtually ensured that its rate of emissions growth would begin bending downward before 2030, on account of the lead time needed to overcome the “inertia” built into the factors that collectively determine emission levels. Moreover, the commitment from Beijing conferred instant legitimacy on political forces within China favoring clean energy and seeking relief from relentless air pollution that kills an estimated 1.6 million Chinese a year–no small matter in a society that operates according to perceived political and cultural authority.

The prime mover in the flattening of China’s CO2 emissions was the downturn in its use of coal. As CTC intern Cristina Mendez pointed out in her April 2017 post, coal use began declining in 2013. Prior to then, this dirtiest fossil fuel was the mainstay of China’s energy economy, not only in power generation but in industrial production and even provision of heat. Available data indicated that China’s coal use tripled in just 15 years to 2013 to exceed coal use by the entire rest of the world. Coal accounted for more than 60 percent of the country’s primary energy, i.e., half-again as much as China’s hydro-electricity, nuclear power, petroleum, natural gas, and wind and solar energy combined. By any measure, the relentless increase in China’s combustion of coal was both the engine driving China’s astounding economic growth and the single biggest cause of surging global warming emissions over the past quarter-century.

Still No China Carbon Tax

Periodic rumors notwithstanding, China does not administer any carbon tax. Seven pilot carbon cap-and-trade programs have operated in Guangdong, Shanghai and Shenzhene provinces, among others, and these paved the way for the September 2015 announcement by President Xi Jinping at the White House that China intended to inaugurate a nationwide cap-and-trade system in 2017.

Here’s how CTC senior policy analyst James Handley reported this development at the time:

China’s announcement last month that it will begin implementing a national cap-and-trade system for greenhouse gas emissions in 2017 is welcome news. Not only because it signals (again) that the world’s largest emitter may be starting to tackle global warming (and conventional air pollution), but because it tosses another shovelful of dirt on a longtime U.S. excuse for inaction.

Reports on China’s announcement nevertheless raised concern about whether China (or any government) can implement and enforce such a complex, opaque system. A decade in, the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme has proven only weakly effective. The EU has struggled to remedy numerous design and implementation flaws including a too-loose cap that has failed to induce a significant, persistent and rising carbon price, as well as international offsets that hold down carbon prices and whose environmental benefits remain maddeningly difficult to monitor and verify.

Moreover, the opacity of permit-based trading systems appears well-suited to China’s particularly corrupt form of “crony capitalism.” And another possible motivation for China’s choice of cap-and-trade over a transparent and easier-to-administer carbon tax is Beijing’s history of profiteering from questionable carbon offsets; these could expand if China can link with lucrative carbon markets in the west.

If China does proceed with cap-and-trade, it would be wise to build in a price floor to assure a clear minimum carbon price―a “patch” that the EU has thus far failed to enact.

Related concerns suffused a thoughtful analysis in the New York Times, China Faces Major Obstacles in Plan to Cut Greenhouse Gases, Experts Say. (The digital version’s headline was a somewhat watered-down, “Enacting Cap-and-Trade Will Present Challenges Under China’s System.” But the subhead pulled no punches: “With its heavy-handed interventions, poor statistics and corruption, China will need years to build a market that substantially cuts emissions, experts said.”)

Earlier, in late 2014, researchers at Resources for the Future led by analyst Clayton Munnings published a detailed analysis of three of China’s regional cap-and-trade pilots. Their report suggested that Chinese authorities faced high hurdles in program design, information provision and political acceptability if the eventual national program is to put an effective “price on carbon” and actually constrain and reduce emissions.