The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed a severe care crisis throughout the world. The measures to contain the infection–lockdown, social distancing, quarantine–severely disrupted activities crucial to the basic functioning of society from cooking to cleaning, childcare, elder care and more. The experience of China shows the critical role of the community in providing essential services.

Like in many other countries, women in China assume disproportionately more care responsibilities than men. With the care crisis intensified by the pandemic, women from different socioeconomic backgrounds were all significantly affected. Urban women mostly saw themselves shouldering more household chores when hiring domestic workers or seeking extra help from family members became impossible or difficult during the lockdown. As most female migrant workers are employed in the precarious informal sector, they had to endure job losses and economic hardship, in addition to extra childcare and household chores. Female healthcare professionals risked their health working on the frontline while having to bear the added mental stress of possibly carrying the virus and spreading it to family members.

Facing such a severe crisis, the neighborhood communities which have always been part of the social infrastructure, all of a sudden stood out to be focal points of care service provision. The term “community” in China today refers to residential neighborhoods in urban areas and villages in rural area. Its rise can be traced back to the withering of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) during the late 1980s. Prior to the 1980s, SOEs were not only the physical sites for production, but also served as the employment-based social infrastructure, providing free or affordable social reproduction services, including on-site childcare, schooling, and healthcare services. Following the privatization of the SOEs and the collapse of the employment-based social infrastructure, the government launched the “community building” project in the hope that they could serve as a middle ground to partly address the large-scale social problems emerging from the rapid social transformation, care responsibilities were shoveled back to families all at once.

Against this backdrop, the neighborhood communities were able to integrate both central state and locally-mobilized resources. With years of management experiences working alongside the local neighborhoods, the formally employed neighborhood community staff were able to adjust to the new demands arising from the pandemic swiftly. As a result, throughout the urban and rural sectors, these neighborhood communities not only ensured provision of basic necessities when human mobility was restricted but also facilitated quarantine practices in a way that largely relieved family members from assuming extra care responsibilities.

During the Wuhan lockdown, neighborhood community councils were responsible for disseminating virus-control medical advice as well as delivering food and medicine to every household, so unnecessary movement of people could be minimized. By doing so, community workers and volunteers took up a large portion of household chores (i.e. grocery and medicines shopping) and helped reduce stress imposed upon individual households. In contrast, we see photos of people holding shopping carts outside the grocery stores waiting for hours to get in at the beginning of the pandemic in the U.S. and many other countries, a practice that is both risky health-wise and inefficient time-wise.

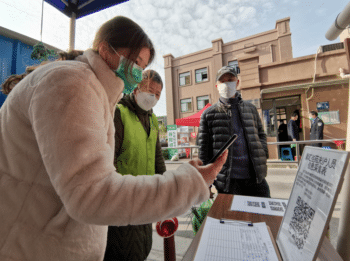

Neighborhood-based community organizations also helped with coordinating health screening and contact tracing, which is crucial in containing the virus. Community workers and volunteers, taking advantage of their familiarity with local neighborhood, were able to keep close contact with families–effectively screen febrile patients–and transfer them to quarantine sites for medical observation or to fever clinics for diagnosis. In Wuhan, community clinics and public health centers also provided care to affected patients with severe symptoms, relieving the pressure from hospitals during the early lockdown, when resources were limited. Additionally, they took the responsibility of providing psychological comfort to neighborhood residents.

In places like Shanghai where all cases were imported, all 246 community clinics remained open during the lockdown to guarantee the access of unaffected patients to basic healthcare services. For people coming back to China via international flights, the community also took the lead in ensuring safety through implementing protocols such as airport pick-ups to ensure proper quarantine measures. The entire process is as follows: travelers arriving from abroad were picked up from the airport via designated transportation, usually accompanied by two people from the community council, one doctor from the community clinic, and one public security worker. This four-person group would first send arriving passengers for testing, then to hotels while waiting for the results, and finally for home-quarantine if the results were clear. They also established close contact with the people during the fourteen-day home-quarantine, monitoring their health conditions while providing needed assistance, making it feasible for the arrivals to stay housebound. Family members were largely relieved from all responsibilities throughout the process which bore health risks. This procedure was particularly helpful to family members who are immunocompromised or suffering from pre-exiting conditions, who would be at an increased risk if they had to have direct contact with people that had recently traveled.

It is worth noting that China is not the only country utilizing community organizations to enforce and coordinate isolation and quarantine operations, which have proven to be the most crucial step in stopping the spread of the virus.

In Venezuela, for instance, communes work as part of the community infrastructure and played crucial roles in imparting knowledge on COVID-19 prevention and coordinating quarantines. Commune doctors had gathered information on individual households prior to the pandemic, which helped them to quickly identify the most vulnerable members with extra physical and psychological needs. Before the pandemic even hit Venezuela, doctors had already started to make house-to-house visits to inform residents about the nature of the virus and ways to avoid catching it. Such preventative methods are labor-intensive and costly time-wise, yet in the context of a pandemic, it has proven to be an extremely prescient method that helps to save an immense amount of resources in the treatment stage.

The case of the state of Kerala in India is also exemplary. Its cooperatives, as part of the institutional structure, not only effectively facilitated quarantine and contact tracing as in the case of Venezuela, but some even assumed essential production functions such as aiding in mask and sanitizer production to support the prevention of virus spread.

Of course, not every country or region is equipped with pre-existing community infrastructure in place like China, Venezuela, or Kerala. But that doesn’t mean the importance of community-level organizations can be ignored as the pandemic unfolds. Taiwan, for instance, has struggled to mobilize limited public resources to provide ad hoc support at the community level. In addition to applying technology (i.e. big data and cell phone signals) for contact-tracing and quarantine monitoring, borough chiefs (the lowest-level elected officials) were made to check on people daily during the quarantine. They were also tasked with assisting people with grocery shopping and occasionally providing psychological comfort. With a small population and only imported cases to face, Taiwan’s ad hoc community-level services proved to be extremely effective in enforcing quarantine, although borough chiefs and other temporarily mobilized staffs were overwhelmed with all these additional tasks induced by the pandemic.

All the above-mentioned cases suggest that, it is necessary to institutionalize the community-level organizations as part of the social infrastructure to guarantee the delivery of essential care services. Just like public transportation needs physical infrastructure (i.e. railroad and subways) as its platform to carry out its services, care services, along with other social services (i.e. education and medical services), also need social infrastructure to facilitate their delivery to the recipients.

In our understanding, community should act as a platform to mobilize state as well as local resources, while also developing its potential to provide decent jobs and promote long-term human development. This implication is valid for the current pandemic-ridden world, and particularly for the Global South.

From the economic perspective, countries in the Global South have abundant labor resources, which is conducive to the labor-intensive nature of care work. With limited public resources, it is crucial to determine where and how to invest to bring about the best possible outcome for the society. In this sense, employing the relatively less costly labor resources into the building of a universally accessible, community-centered social infrastructure for care provision is feasible cost-wise in the short run. When care services become universally accessible, it will also foster a healthy cycle of social reproduction, which could improve labor productivity and contribute to the development of the economy in the long run.

Another significant aspect of implementing care-work concerns large-scale geographic and socioeconomic dispersion in Global South countries. Some communities are still largely agrarian, so urban community management experiences will not be universally applicable. This makes specific local knowledge extremely important in the effective provision of care services in residential neighborhoods across different regions. Thus, community-based organizations with trained local leaders will be in an advantageous position in terms of understanding the local conditions and providing the most locally-targeted support, as compared with top-down state policies or NGOs funded through foreign sources.

Although it is important that local communities have their autonomy in deciding priorities and allocating resources, it is also crucial not to overemphasize autonomy to the extent of promoting localism, allowing only spontaneously established communities to exist, or by excluding any form of state involvement in the community building initiatives. This is because, among all, countries in the Global South are inflicted with uneven distribution of human and material resources across regions, and even more so in local neighborhoods. Leaving local neighborhoods alone to mobilize resources for the building of long-standing community organizations will only lead to further polarization, with the best services available to communities endowed with human and financial resources in the first place. In this case, only a consistent and non-exclusive institutional support of resources (such as in the form of state partnership) can alleviate existing inequality.

To conclude, the COVID-19 induced care crisis and its gendered impact suggests that privatized and family-based care provision are too institutionally weak to fight against a crisis at the scale of a pandemic. Like China, most Global South countries adopting the neoliberal type of market reform have experienced privatization of public service sectors in the past few decades, which have contributed to the current care crisis. The difference lies in that in China, both the institutional memory and physical infrastructure for a public option of care provision still remain, and so they can be utilized to a great extent in the time of crisis. In this sense, China’s history of dismantling of SOE-based public care services and the social crisis it brought about, as well as its heavy reliance on community organizations in the current pandemic, should be important lessons for other countries to contemplate long-term solutions to address the care crisis that will almost certainly outlive the current pandemic.

Ying Chen is Assistant Professor of Economics at the New School as well as Faculty Affiliate at the India China Institute. Her research areas include political economy, ecological economics and development economics.