Introduction

Roughly 19 million people in Brazil have gone hungry during the COVID-19 pandemic and more than 116 million people (52% of the population) experienced some level of food insecurity, according to Brazilian Research Network on Food and Nutritional Sovereignty and Security (Rede PENSSAN).

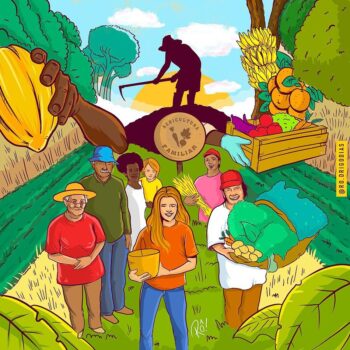

Gabriela Tornai (@gabrielatornai_) / Design Ativista / 2021

For those who follow Brazilian politics, even superficially, it should not be news that the country is living through its biggest crisis since the civic-military dictatorship ended in the 1980s, or even – according to some–in the entire history of the Brazilian Republic since the deposition of Emperor Pedro II in 1889. Brazil is facing tremendous political and social setbacks led by its far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who has not been formally affiliated with a political party since 2019 but still relies on the social support and approval of the country’s ruling classes and Armed Forces.

If the social consequences of adopting an ultra-neoliberal project weren’t enough already, the emergence of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 and the gross mismanagement and negligence in combatting the virus have led to the worst-case social, economic, and health scenarios. The government’s neglect when it comes to both the disease and science is evident through sheer numbers: more than 400,000 people have died from COVID-19 in Brazil as of April 2021, or 3,000 people per day. With the emergence of new variants of the virus and the collapse of the healthcare system a year after the coronavirus first hit Brazil in March 2020, the country has become a threat to the world.1

Meanwhile, the Brazilian left–which has been defeated in all of the great political battles of the past decade–aims to regroup and recreate its social base as it tries to regain the political stewardship of the country. How did we end up in this situation? What are the possibilities for engaging society in a way out of the crisis?

Dossier no. 40, The Challenges Facing Brazil’s Left, by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research analyses the challenges facing the Brazilian left in today’s political context. This is not a simple task to carry out, both because of the number of progressive forces and the diversity among them and because of the complexity of the political situation in Brazil. For this reason, we chose to speak with different representatives of the working classes to help us in this process. We interviewed Élida Elena, the vice president of the National Union of Students (UNE) and a member of the Popular Youth Uprising (Levante Popular da Juventude); Jandyra Uehara of the National Executive Board of the Unified Workers’ Central (CUT); Juliano Medeiros, national chair of the Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL); Kelli Mafort of the national board of the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST); Gleisi Hoffmann, a federal deputy and chair of the Workers’ Party (PT); and Valério Arcary, a professor at the Federal Institute of São Paulo (IFSP) and a member of the national board of the PSOL.

The dossier is broken down into five sections. The first section assesses the paths followed by the Brazilian left in recent years; the second analyses the ruptures and reconciliations of right-wing forces; the third discusses instruments to foster unity; and the fourth assesses the challenges of building a popular base.2 Lastly, the fifth section reflects on the role of the country’s most significant popular leader: former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

The images featured throughout this dossier are part of the project Activist Design (Design Ativista), a collective that emerged during the 2018 elections in Brazil with the aim of promoting the creation and distribution of free art and information, combatting fake news, and supporting democracy. During this period, the collective called for the submission of visual works of art and promoted design marathons and large gatherings during which they debated the role of design in contributing to the creation of a more humane and democratic society.

Assessing the State of Brazil’s Left Today

The number of deaths caused by COVID-19 in 2021 has already surpassed the total deaths in 2020. From the first case on 12 March to 31 December 2020, there were 194,949 deaths; this year, there have already been more than 200,000.

Letícia Ribeiro (@telurica.x) / Design Ativista / 2019

Many of the defeats that the Brazilian left has suffered in recent decades are a result of the strategic understanding that dominated this sector, according to political organisations and experts. This view prioritised the institutional struggle driven by the Workers’ Party (PT) in its thirteen years in power at the expense of deep structural reforms that could provide the working class with an opening to take over the Brazilian State.

Without a doubt, the policies implemented by the Workers’ Party administrations have greatly improved the lives of a large part of the Brazilian population. Among these many measures are the income redistribution policy Bolsa Família (‘Family Grant’), responsible for lifting 36 million people out of extreme poverty;3 the housing programme Minha Casa Minha Vida (‘My House My Life’), which has built more than 4 million working-class homes;4 the increase in the minimum wage above the rate of inflation; the increase in formal employment; the reduction of social inequality; and the increase the enrolment of youth from urban peripheries in public and private universities. Undoubtedly, the rise of the Workers’ Party to the Executive Branch was also connected to the progressive wave that swept across Latin America in the late 1990s and early 2000s, victories that were propelled by the consequences of neoliberal policies across the continent.

However, much of the criticism centres around the fact that the Workers’ Party made the political decision to garner support from different classes and implement socio-economic measures without following a process to politically educate the great majority of workers. As a result, this process failed to increase the level of class consciousness among middle and working-class sectors. The consequences of this became more evident with the coup against former President Dilma Rousseff (PT) in 2016, which was unable to count on a process of massive resistance capable of overturning the result of the impeachment proceedings. The election of Bolsonaro with 57.8 million votes (55%) two years later further reinforced this lesson.

‘Even though investing in the reduction of social inequality in Brazil took centre stage under the progressive governments during this time, organising the working class was not prioritised, and neither was the ideological struggle in society. When the coup took place, the Workers’ Party was not able to rely on those who had benefited from their policies [to stop it]: the working class’, Élida Elena (UNE) told us. Elena told us that after Dilma Rousseff left office, the working-class suffered attacks that sought to undermine their ability to fight back, such as the weakening of labour rights and labour union organisations. ‘Therefore, we argue that the Brazilian left has suffered a strategic defeat and that the correlation of forces in society is unfavourable to us’.

Kelli Mafort (MST) believes that the many consecutive defeats suffered by the Brazilian left do not signify a strategic defeat, which happens when a class is neutralised by another political actor. ‘We have certainly accumulated many political defeats, but the working class is still alive and resisting in face of the impacts of the crises of capital’.

The last successful strategy put forward to further the interests of the working class in Brazil was the popular democratic strategy (estratégia Democrático-Popular). This strategy was born in the struggle for a democratic transition at the end of the civic-military dictatorship and was at the heart of the rise of mass struggles in the late 1970s and 1980s.

The popular democratic strategy is grounded in three firm beliefs:

- That the development of Brazilian capitalism has failed to accomplish the tasks of the bourgeois revolution (agrarian reform, regional and social inequalities, consolidation of a democratic order, etc.);

- Tthat these tasks cannot be tackled in alliance with the domestic bourgeoisie; rather, their leading figures are the working classes (rural and urban workers and other segments exploited by capitalism); and

- That the path toward accomplishing this strategy is to join forces with a strong mass movement combined with institutional victories that reach the level of the presidential office and accomplish a number of reforms introduced within the popular democratic strategy (against monopolies, big, landed estates, and imperialism).

The popular democratic strategy combined two fundamental tactics. First, it sought to gain control over institutions by consolidating power within the state through municipal, state, and federal elections. Second, it sought to mobilise the working class through strikes, land occupations, mobilisations, and mass struggles.

However, Mafort explains that, ‘as the popular democratic strategy was put into practice, these tactics grew apart, and the tactic of [working through] institutions gradually overtook [the tactic of] working-class mobilisation. As this happened, what was once a tactic became a strategy; [this shift] led organisations to prioritise working within the state over building the strength of organisations. In addition, there was a series of political missteps that failed to make a distinction between the government and the organisational instrument of the working class during the neo-developmentalist administrations of Lula and Dilma’.

Along the same lines, Juliano Medeiros (PSOL) points out that it is impossible not to acknowledge the defeat of ‘a strategy that has limited its perspective to the management of the state, the rules of the game of liberal democracy, [and] the improvement of living conditions, but without structural reforms’. Medeiros explained that ‘part of the left chose to promote changes from the state, which weakened its contact with working-class sectors. Forms of sociability that emerged in the process of democratisation of Brazilian society in the 1980s were replaced with others that are ingrained with neoliberal ideology and individualism. And this happened because the left moved away from organising on the ground [where people live and socialise] in order to wage the righteous and necessary struggle through [governmental] institutions, but this allowed the enemy to occupy these spaces’. The power vacuum that Medeiros referenced has enabled the rise of the far right. As Jandyra Uehara (CUT) points out, the inability of left-wing sectors to react properly did not ‘strike like a thunderbolt from a clear sky’; rather, it was the ‘result of nearly three decades of a politics of class conciliation; of the weakening of the [working-class] programme; of the prevalence of the institutional and electoral struggles detached from building a base, political education, and the ideological struggle of the working class’.

As the union leader herself pointed out, such a defeat is not only about the mistakes of the left, but also about an offensive by the right, spearheaded in particular by major media outlets. Since the beginning of the Workers’ Party administrations, the mainstream media has built a narrative that criminalises politics in order to sever society from the political debate. This criminalises the Workers’ Party in particular and the left as a whole by creating an image of the left as corrupt and controlled by ‘the system’.

Valério Arcary (PSOL) speaks about the tactical short-sightedness of the left, which has underestimated ‘the danger that threatened us’. Arcary listed a sequence of events that fell into this category: ‘[Operation] Car Wash was underestimated, followed by the significance of the impeachment and the opportunity to criminalise the left and Lula; then, the imminence of Lula’s arrest; then, finally, the threat represented by Bolsonaro. Underestimating the power of class enemies was fatal’.

Arcary refers to the consecutive analytical mistakes made by the Brazilian left in recent years when the right began to intensify its offensive. For example, it took a significant sector of progressive forces a long time to understand the implications of Operation Car Wash.5

Launched in 2014, Operation Car Wash was an effort spearheaded by the trial court judge Sergio Moro, allegedly aiming to investigate reports of corruption involving the Brazil’s state energy company Petrobras’s contracts with big construction firms. Operation Car Wash became the primary tool to delegitimise and carry out the political persecution of Presidents Dilma Rousseff and Lula. The main objective of the operation was to incriminate Lula, even if through highly questionable accusations with no evidence. What was allegedly an operation to fight corruption turned out to be a series of political trials.

When the process that removed Dilma Rousseff from office began, some sectors did not believe that such an initiative by the Parliament would succeed. They argued that the economic policy of the Workers’ Party president was already benefiting the ruling class and the bourgeoisie would not be interested in political instability.6

Again, years later, many did not believe that former President Lula would be arrested because–as they argued at the time–the right would be afraid that his imprisonment would incite working-class uprisings. However, when Judge Sergio Moro issued an arrest warrant against Lula in 2017 to bar Lula from running for president, and when Lula was eventually arrested in 2018, this did not happen. Then, when Bolsonaro announced that he would run for president in 2018, many estimated that support for the former captain of the Brazilian Army would not be higher than 8%. However, Bolsonaro took the lead in the first round of elections and won with 55% of the vote in the second round against Fernando Haddad of the Workers’ Party.

In the face of so many obstacles, the strong influence of neoliberal ideology, individualism, and entrepreneurship found no serious opponent in a weakening socialist ideology, whose organisations, on the whole, abandoned their anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist characteristics and put building a base on the backburner, instead dedicating their efforts to institutional and electoral struggles.

Brazil began 2021 with record levels of unemployment: 14,272 people (14.2%) were in this situation according to Brazil’s National Household Sample Survey (PNAD).

Rafael Olinto (@rafa_olin) / Design Ativista / 2020

Jandyra Uehara (CUT) explained that a fertile ground emerged for the right to win over ‘a working class, the majority of which is mostly unorganised and is not under the permanent influence of unions, people’s movements, or left-wing parties, which have little by little abandoned areas [where they once organised their political struggle], instead prioritising corporate and economistic struggles, as well as election races. Meanwhile, the instruments of the right wing to wage a political and ideological struggle have taken root in the areas where the working class lives’.

The Tragic Repetition of History

Soon after the 2008 economic crisis, the U.S. led a new neoliberal offensive, seeking to regain global hegemony and control. Meanwhile in Brazil, the complex political and class composition of the Workers’ Party administrations began to exhaust itself under the influence of imperialist strategies. It was no longer possible to maintain the gains for the bourgeoisie without cutting back on workers’ rights. The breakup between the ruling class and the Workers’ Party government was designed step by step, guided by the invisible hand of U.S. imperialism.

In 2014, Aécio Neves of the liberal right Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) lost to Dilma Rousseff in the presidential race. After failing to implement a full-fledged neoliberal project through an electoral process, the hegemonic sectors of the Brazilian bourgeoisie pivoted to two different tactics. First, they launched impeachment proceedings against Dilma Rousseff; then, later, they barred Lula from running for president and endorsed the presidential bid of Jair Bolsonaro. An authoritarian figure with neofascist traits, Bolsonaro was the only candidate who seemed capable of winning over the Workers’ Party in the 2018 elections.

Soon after the coup that ousted Dilma, a strong and successful neoliberal and austerity agenda began to be implemented to dismantle the victories achieved over the course of thirteen years of Workers’ Party governments. The state was weakened, allowing the Brazilian and international bourgeoisies to plunder a significant amount of public resources. The country unconditionally realigned with the United States in all international affairs, forums, and bodies and became blatantly involved in the international campaign against Venezuela and the process of the Bolivarian Revolution.

Five years after the coup and two years after the election of Bolsonaro, Brazil has become immersed in the biggest economic, social, political, environmental, and health tragedy in its history as an independent republic.7 The federal government’s mismanagement of the health crisis has led the country–alongside India–to become the epicentre of the pandemic as of March-April 2021, a moment when the transmission of the virus had begun to slow down on a global level. The convergence of these crises has profoundly impacted the worsening living conditions of the people and has led to an increase in hunger and poverty as well as new variants of the coronavirus and the collapse of the healthcare system.8

The pandemic is only getting worse in the face of the deliberately genocidal policies of the Bolsonaro administration. The government still has not taken action to control and fight the virus, which is exponentially increasing the number of deaths of people who are not receiving care. This has led the liberal right to slowly and gradually withdraw its support from the government.9 While there is some discomfort with more authoritarian speeches and the paths taken to fight the pandemic, the right continues to support the implementation of the ultra-neoliberal project that attacks labour and social rights.

‘The prevalence of the political conflict between the far-right and the traditional [liberal] right is concretely grounded in disagreements and contradictions about the control of institutional apparatuses that structure the limited democracy we have in Brazil’, Jandyra (CUT) explains. ‘This is especially the case with the STF [Supreme Court] and other apparatuses of the justice system and the National Congress. This unity around the neoliberal programme is one of the pillars of the genocidal Bolsonaro administration’s resilience. The military and Bolsonaro’s base of popular support, which is, to a great extent, built within evangelical churches, are two other pillars of support [for Bosonaro]’. She argues that, for most of the right, Bolsonaro does not represent an end in itself, but only ‘one of the means to implement ultraliberal policies’.

In addition to the backing of a large part of the domestic bourgeoisie, Valério Arcary (PSOL) draws attention to four other pillars of Bolsonaro’s support:

- the unbelievable support of roughly one third of the Brazilian population, even amidst the health chaos;10

- the demoralising effects of the cumulative defeats experienced by the working class;

- the weakness of existing alternatives to Bolsonaro; and

- the pandemic itself, which imposes limits on the working class’s ability to mobilise.

Roughly speaking, the current Brazilian political spectrum is composed of four broad sectors: the far-right, liberal right, centre-left, and left. ‘Which of these sectors are still seeking a [political] project? That’s exactly the centre-left and the liberal right. The crisis of democracy has strengthened the extremes’, Juliano Medeiros (PSOL) told us.

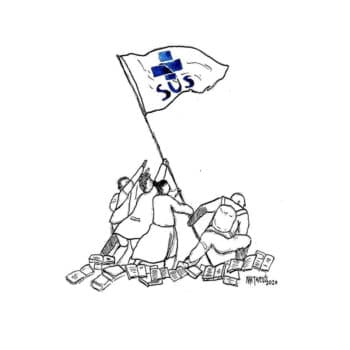

At the beginning of the pandemic, Brazil was the Latin American country with the best conditions to confront COVID-19, thanks to the structure of the National Healthcare System (SUS). However, the government managed to deliberately boycott the health system, as a study conducted by the University of Michigan and the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV) shows.

Matheus Miguel (@poesianasestrelas) / Design Ativista / 2020

Meanwhile, Kelli Mafort (MST) believes that the principal conflict is taking place between the left and the far right, since the liberal right has lost its influence. Now, the liberal right’s biggest problem is finding a political leader who can engage with the people. However, she notes that it is ‘always important to remember that the far right and the [liberal] right are two sides of the same coin: the bourgeois class. We must move against this class through the legitimacy granted to us by the working class and by firmly opposing capital’.

A Broad Front Versus a Left Front

Valério Arcary (PSOL) argues that the objective conditions to overthrow Bolsonaro are so ripe amidst the collapse of the health system that these conditions are already beginning to rot, and they evolve faster than the subjective conditions. However, there is a dispute for hegemony between the sectors that oppose the far right government: the left and the liberal right. Arcary believes that ‘the experience of 100 years of struggle against the far right, especially when the far right is led by a political current with fascist characteristics, demonstrates that a broad left front is the best tactic’. This is not because the left wouldn’t be willing to join forces with the liberal right to fight against the far right, ‘but because the liberal right fears, and rightfully so, that the social crisis may provide an opening for a left government’.

For Jandyra Uehara (CUT), the slogan ‘Out with Bolsonaro’ could bring together sectors among the left and centre-right [liberal right] as the crisis gets worse. But a broad front alliance bringing together all of those in opposition to the current fascistic onslaught–advocated by some sectors of the left and the centre-left–would, in her opinion, lead these forces to adopt a two-stage approach to the social-historical process. This approach would separate the struggle for democratic freedoms from the struggle in defence of rights and national sovereignty. If this approach prevails, Uehara predicts that the left will become a hostage of the liberal right, making it even harder to overturn the neoliberal project implemented in recent years. ‘From our point of view, there is no possibility of putting an end to [this project] without breaking from it [completely], and there is no national unity when the price to pay is to keep the people in a state of deprivation, under the rule of severe exploitation, and entrenched in deepening inequalities in a subordinate Brazil in the periphery of capitalism’.

This view contrasts with the tactic envisioned by Gleisi Hoffmann (PT), who believes that to face the crisis experienced in Brazil, a broader political alliance is needed, ‘not necessarily an electoral [alliance], [but] to bring together all political, social, and cultural sectors who fight for vaccines, emergency aid, and jobs’, as well as those who fight to defeat Bolsonaro under the slogan ‘Fora Bolsonaro (“Out with Bolsonaro”)’.

This interpretation is more in line with the analysis provided by Élida Elena (UNE), who supports the combination of two fronts: a popular left front and a democratic front. ‘The fundamental lesson … [here] is that the democratic question is interwoven with the social question, which is exacerbated as a result of the severe crisis of capitalism. It is about defending democracy, albeit a deteriorated democracy, because this is the most appropriate site to wage a political struggle. It is necessary to avoid the formation of a police state or even a fascist political regime where the conditions for working-class struggle and organisation would be substantially unfavourable’. This would mean building a democratic front and bringing together various sectors of society to defend democracy and to erode, isolate, and defeat neofascism.

Elena believes that it is necessary to continue building and strengthening a working-class left front, ‘with a strategic character, to accumulate forces for a democratic and popular way out of Brazil’s crisis. This involves defending the social rights of the people, the struggles of Black people against racism and against all historical oppressions that weigh down Brazilian workers, and the unrelenting fight against the neoliberal policy of [Minister of Economy] Paulo Guedes’.

Both the Frente Brasil Popular (‘Popular Brazil Front’) and the Frente Povo Sem Medo (‘People Without Fear Front’) formed in 2015, each uniting dozens of left-wing political organisations. Frente Brasil Popular is broader in nature and focuses on strengthening political parties, while Frente Povo Sem Medo is made up exclusively of social and labour movements. The two fronts are necessary for building a political project and a project for the nation. Both have been playing an important role in working-class organising and building unity with the centre-left in the struggle against neoliberal reforms.

Regardless of which tactic is used, there is a consensus about the need to build paths to move beyond and soften the blows of the reality at hand, as Kelli Mafort points out. She says that the MST has chosen, for now, not to focus efforts on building unity around their political programme and vision ‘because our assessment is that doing so in times of declining mass struggles could lead to mistakes resulting from overly-academic views or mistakes resulting from a struggle over hegemony that doesn’t contribute at all to the advance of class struggle. Therefore, we have looked to engage in building unity around political demands, always having reality as the primary grounds for our formulations.

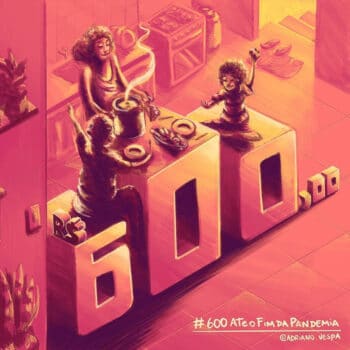

Unity around more immediate political demands has created unity in action among the Brazilian left, as shown in the example of three key demands: vaccine access for the people, emergency aid of R$600 per month, and the impeachment of Bolsonaro.

‘We are living in a moment of political reflection so that we can improve strategic projection, and this includes facing the fragmentation among the campo popular [social movements and organisations] and the left as well as facing the struggle for hegemony and the excessive focus on tactics over long-term strategy. We aim to build unity around key issues while fostering experiences that can provide us with collective political knowledge that is accumulated over time through the process of building a base, political education, and preparation for more offensive struggles’, Kelli Mafort (MST) said.

Without a doubt, achieving unity has long been a challenge and a historic need for the left as a whole. In this sense, Élida Elena (UNE) believes that the fragmentation of the left will cost it dearly. This could lead to two scenarios: on the one hand, an electoral win for Bolsonarism and an accelerated rise of fascism in society or, on the other hand, the formation of an alternative liberal right, which will continue the neoliberal economic project.

Just over 68 million people received R$600/month in emergency aid in 2020. In 2021, this aid is more limited and will be distributed in four payments that range from R$150 to 375 depending on the family.

Adriano Vespa (@adriano.vespa) / Design Ativista / 2021

‘If we fragment ourselves, no left force will win. We must have a favourable environment without struggling for hegemony, with respect for differences, through a tactic that unites us around what is more relevant than specific organisational demands–and that is defeating the rise of neofascism in Brazil’, she adds.

Building the Base

Though present in the words of most left organisations, for years progressive sectors in Brazil–the country of Paulo Freire, who would have turned 100-years-old in 2021–have struggled to consolidate, strengthen, and build a base that is capable of re-establishing trust among the masses and changing the correlation of forces in society. Nevertheless, virtually all segments of the left agree that regaining an understanding of building a base is a necessary strategy, alongside waging an ideological battle and becoming involved in the peripheries in a more permanent way. This is seen as a central element in rebuilding strength among the people, defeating Bolsonarism, and making structural reforms the order of the day on the path to seizing power.

According to Valério Arcary (PSOL), the most active sectors of the left’s social base are becoming stronger. ‘Changes in the consciousness of the masses are key for their willingness to fight, for their spirits, moral strength, and self-confidence. Before class positions can change, consciousness needs to be transformed. When something seemingly impossible happens and comes as a surprise, expectations increase’.

Élida Elena (UNE) notes that ‘in order to be ready for this moment, we are counting on building a tactic of active defence, which aims to resist setbacks while creating the conditions to advance to an offensive position. Today, our task is to isolate, erode, and defeat Bolsonarism. Broadening our bond with the working class is essential. To do this, we rely on a politics of solidarity as a way to expand our resistance’.

Because life is not always a bed of roses, Élida Elena (UNE) points out a number of realities that make it more difficult to build a base in the peripheries. Acknowledging them is fundamental in order to be able to progress in building strength in working-class areas. Among these realities are organised crime, which makes it difficult to build methodologies to carry out base building work; the prevalence of neo-Pentecostal churches, which operate based on a more conservative perspective and are able to provide responses for people’s material living conditions; and the very vulnerable living conditions in the peripheries, which place the struggle for daily survival before working-class organising. Adding to these challenges are the loss of workers’ autonomy, the increasingly precarious nature of work, the dismantling of the working class’ tools for organising, the elimination of rights, and the increase in social, racial, and gender-based segregation.

Brazil began 2021 with more people living in poverty than a decade earlier;, in 2011, and 27 million people (12.8% of the population) are now living on less than R$246 per month (R$8.20 per day) according to the Getúlio Vargas Foundation.

Rodrigo Dias (@ro.drigodias) / Design Ativista / 2021

As the living conditions of the working class got worse, a sector of the left made the decision to carry out actions of solidarity to fight the coronavirus pandemic as well as the hunger pandemic, and base building was taken up once again. Activists got involved in numerous solidarity initiatives, organising community kitchens, and donating food, personal hygiene kits, masks, and blood. One of these actions became known as Periferia Viva (‘The Periphery Lives’), a platform that brings together several working-class movements to build class solidarity. Perferia Viva’s work combines gestures of solidarity with the work of building a base, which includes creating organic relationships between households through Agentes Populares (‘Community Agents’). The methodology of the Agentes Populares project is to train people from the community to engage in solidarity actions; the ‘agents’ work with a set of households, with the objective that they will become active in their places of residence and become responsible for a certain number of families. These ‘agents’ work to provide healthcare and food as well as to ensure that the community’s rights are respected, which fosters cooperation and mutual aid. Élida Elena (UNE) explains that ‘We understand the politics of solidarity as one of the priority strategies for building a base in the peripheries day to day. This is an important political response to the conjuncture that we are living in and part of the tactical approach of active defence; it offers concrete answers to the advance of neoliberalism’.

Lula’s Return to Politics

Between March and April, the Supreme Court granted two claims filed by the defence of former President Lula, restoring the political rights that had been taken from him in 2018. One of these claims established that former Federal Judge Sergio Moro did not have jurisdiction to try cases in which Lula had been a defendant, thus overturning all convictions against the former president. Through the other claim, the Supreme Court acknowledged that Moro was biased in his ruling against Lula in one of the cases, which had resulted in his imprisonment for 580 days. Though it is possible that there will be new developments in these cases (however unlikely this is), as it stands, Lula’s entry into electoral politics shifts the political scenario in Brazil and raises the question: what led the Supreme Court to make these decisions, since, up to that point, the Supreme Court had been complicit with Operation Car Wash?

Regardless of what led to these decisions, it is clear is that part of the liberal right is once again looking for a way to come out on top in the current crisis. Though the recent rulings have not been the result of working-class mobilisations, the efforts of the Brazilian left to have Lula’s political rights restored must be acknowledged. Gleisi Hoffmann (PT) points out that restoring Lula’s political rights has increased the progressive sector’s will to come together to face the far right and sectors of the liberal right: ‘[Lula] is the political leader who is the best suited to build this [unity]’, he said. ‘Now he is no longer legally barred [from running for office], which increases his ability to mobilise and organise’.

Having Lula back in the political game, Kelli Mafort (MST) believes, ‘has immediate consequences, whether by influencing Bolsonaro’s behaviour, by embarrassing him, or by leading the political coordination with heads of state from other countries that may help Brazil in the face of the current public catastrophe. The Lula factor exercises tremendous influence over the Brazilian left. The urgency of the current situation calls for him to continue to be a leader in solving Brazil’s problems, but it also helps urge activists to carry out base building work, expand solidarity actions, and confront the fascist Bolsonarism [that permeates] the working class’.

For Valério Arcary (PSOL), even though we are still living in a reactionary situation that calls for a defensive position, the possibility of Lula running for president in 2022 has changed the correlation of political forces in Brazil. This represents the biggest democratic political victory of the past five years. ‘Lula has the credential of being the strongest name in the left to get to the runoff election–that is clear. In the conjuncture of a health crisis and an economic recession, this opens the possibility of raising the level of resistance’, she explains. Now that Lula is back in the game, ‘everything changed. We cannot remain silent or wait for 2022 to respond to the need for vaccines and emergency aid for all under the slogan “Out with Bolsonaro”. We are one and a half years away from the 2022 elections. The struggle for a left-wing government must be at the core of the strategy. We need a left that has an instinct for power. But the challenge right now is not about defining who the candidates will be on a national and state level one and a half years in advance’, Arcary adds. This was a consensus among everyone who was interviewed about the 2022 election race.

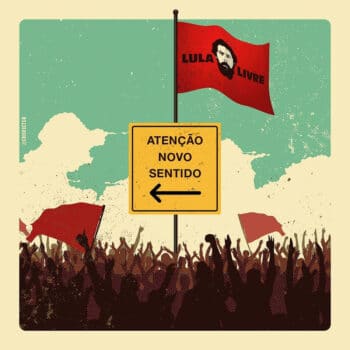

‘Attention: new direction’. Lula’s renewed eligibility to run for president, which had been taken away in 2018, has the potential to change the entire political scenario in Brazil.

Cristiano Siqueira (@crisvector) / Design Ativista / 2019

Élida Elena (UNE) acknowledges that the left has been struggling to engage the working and middle-class sectors in conversation, influence society, and turn demands such as vaccines and emergency aid for all and slogans such as ‘Out with Bolsonaro’ into mass struggles. Lula’s return may change this scenario, though how much this will impact the class struggle is yet to be determined. ‘Obviously, we have limits due to the pandemic; we are relying on activities that have a more symbolic character. With Lula, the ability of our political demands to resonate with the masses changes. The 2022 electoral race is a key battle for the Brazilian left as a whole; we must already be building power among the people to defeat Bolsonarism. And we will only have this ability if we build unity in action and around a programme that is able to present a leftist way out of this crisis’.

Final Considerations

The first conclusion that we can draw from the analyses presented throughout this dossier regarding the challenges posed to the Brazilian left is that the Bolsonaro administration is not likely to be ousted simply through a parliamentary initiative. One possibility, though unlikely, would be for the bourgeois classes to remove Bolsonaro–whom they helped elect–from office if the economic crisis worsens. The more likely possibility, however, is that the bourgeoisie would not remove Bolsonaro immediately; however, they would seek to control the political process in such a way that when they do remove him, they would have an alternative mechanism to maintain their control of the state.

Progressive sectors firmly believe that once health conditions improve following a mass rollout of vaccines, we will see large-scale working-class mobilisations across the country as discontent grows among the population over the measures taken by the federal government. Though Bolsonaro may remain a relevant figure in certain sectors of society, they predict that his popular support will begin to erode.

However, there are differences in opinion regarding the best tactic to build unity. Some advocate building a broad front to confront Bolsonarism, which would bring together all sectors of society that stand up for Brazil’s restricted democracy. Others believe in the possibility of combining two fronts: a broad front as well as a left front that is capable of taking a more structural and critical approach. There is a third political current that believes only in the creation of a left front. For some, this is because they do not believe that it is feasible for sectors of the bourgeoisie to join a broad front, as the liberal right would not agree to join this initiative. For others, this is because they believe that the emergence of two fronts presents a false dichotomy; there should not be a separation between the struggle for democratic freedoms and the struggle in defence of rights and national sovereignty.

Despite the different outlooks on which tactic to adopt, there is a common understanding that only a strong social, political, and popular confrontation will be able to pressure the National Congress to impeach Bolsonaro. Even if he is not impeached, this would still create a different political context for the 2022 elections and open new possibilities for moving forward in the political struggle.

In any case, a way out of this crisis will certainly not emerge in the short term, and it will require a long period of resistance, as Élida Elena (UNE) points out. ‘Neoliberal reforms have deeply marked Brazilian society, and it is in this context that we must apply ourselves to think about the challenges we face’. For this reason, in the section that follows, we have systematised the primary challenges in the short and medium term for the Brazilian left presented throughout this dossier.

Challenges in the Short-term

– Impeach Bolsonaro;

– achieve unity in our actions;

– defend areas that have been organised and secured through struggle: Indigenous communities, areas set aside for agrarian reform, Quilombola11 communities, and spaces of resistance in urban areas;

– demand vaccines for all immediately;

– demand the return of emergency aid with R$600 monthly payments.

Medium-term Challenges

– Deepen and expand base building work by meeting the people’s immediate needs, guided by a politics of solidarity;

– turn these needs into demands of our struggles;

– build processes to legitimise the power of the people;

– carry out political education;

– resume mass struggles (even though taking over the streets is not possible for now, the conditions to resume the struggles must be created over time by combining immediate needs with broader political struggles);

– promote a truly transformative programme within the Brazilian left

According to Jandyra Uehara (CUT), for a democratic, popular solution to succeed, it is necessary to create concrete foundations for cohesion and unity among different segments of the left. ‘In 2021, we must find ways to take up the struggle again and mobilise through parties, unions, working-class movements, Frente Brasil Popular, and Frente Povo Sem Medo. In this process, we must establish commitments in our strategies, tactics, and programme in order to face 2022 and the years that follow’.

Juliano Medeiros (PSOL) believes that ‘we are facing a historic change of huge proportions. This is why we have the opportunity to incorporate a new strategy, to wage an all-out battle against the elites, [to enact] profound changes, to once again have the left present in the areas [where the people live], [and] to radically democratise power. We either change with the changes of our time or we will be wiped off the map’.

Since the beginning of 2021, the Bolsonaro government has slowly begun to deteriorate. Activists in the left are more willing to engage in struggle than in previous years, which could spark a period of more intense mobilisations in the coming years.

Letícia Ribeiro (@telurica.x), photography by Giovanni Marrozzini / Design Ativista / 2019

Even though we are living in a moment in which we have to remain defensive, the window of history seems to be wide open everywhere, igniting a new moment in our current political context. Therefore, it is fundamental that the left defeat Bolsonaro and build unity in its tactics and its programme to be able to provide answers and hope to the Brazilian people. It is vital to reconnect with the working class in order to be able to rekindle mass struggles, to make it possible to contest and build hegemony among working-class sectors. More than ever, it is necessary to draw from the lessons of past struggles and reinvent them so that power is rightly put in the hands of the people–the only force capable of defeating the class enemies.

Bibliography

Antunes, L. Minha casa perto do fim? [‘My House Near the End?’] Uol, Rio de Janeiro, Nov. 2019. economia.uol.com.br.

Antunes, R. Dois anos de desgoverno–a política da caverna [‘Two Years of Misgovernment: The Politics of the Cave’]. A terra é redonda, Feb. 2021. www.ihu.unisinos.br.

Castro, Regina. ‘Observatório COVID-19 aponta maior colapso sanitário e hospitalar da história do Brasil’ [‘COVID-19 Observatory Points to the Biggest Healthcare and Hospital Collapse in Brazil’s History’], Agência Fiocruz de Notícias, 16 March 2021, agencia.fiocruz.br.

‘Intacta, base de Bolsonaro pensa como o presidente na pandemia, mostra Datafolha’ [‘Bolsonaro’s Base Remains Unblemished and Thinks Like The President during the Pandemic, Datafolha shows’], Folha de S.Paulo, March 2021, www1.folha.uol.com.br.

Ministry of Social Development. Plano Brasil Sem Miséria, Cadernos de Resultados [‘Brazil Without Extreme Poverty Plan, Books of Results’]. 2015. www.mds.gov.br.

‘Na íntegra: o que diz a dura carta de banqueiros e economistas com críticas a Bolsonaro e propostas para pandemia’ [‘Read the Full Harsh Letter from Bankers and Economists Criticising Bolsonaro and Proposed Actions for the Pandemic’], BBC News Brasil, 21 March 2021, www.bbc.com.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. Lula and The Battle for Democracy. Dossier 5, June 2018. thetricontinental.org.

Notes:

- ↩ Official numbers from the Ministry of Health as of the writing of this document in April 2021, available at https://covid.saude.gov.br/.

- ↩ Translator’s note: In this dossier, the word popular is translated as ‘popular’ when the meaning implies ‘popular’ or ‘of the people’. Because a literal translation does not always carry the same fluidity, we chose to use the term ‘working-class’ in cases such as ‘working-class homes’ and when referring to classes populares (‘working classes’ or ‘working class sectors’), as this is the closest commonly used substitute in this context.

- ↩ Ministry of Social Development, ‘Plano Brasil Sem Miséria’.

- ↩ Antunes, ‘Minha casa perto do fim?

- ↩ Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Lula and The Battle for Democracy.

- ↩ Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Lula and The Battle for Democracy.

- ↩ Antunes, ‘Dois anos de desgoverno’.

- ↩ Castro, Regina. ‘Observatório COVID-19 aponta maior colapso sanitário e hospitalar da história do Brasil’.

- ↩ BBC News Brasil ‘Na íntegra: o que diz a dura carta de banqueiros e economistas com críticas a Bolsonaro e propostas para pandemia’.

- ↩ Folha de S.Paulo, ‘Intacta, base de Bolsonaro pensa como o presidente na pandemia, mostra Datafolha’.

- ↩ Quilombos are rural communities originally established by Black people who were enslaved in colonial Brazil as a place of resistance and refuge. To this day, many Quilombola communities struggle to be officially acknowledged and fight for the right to their land.