In legislatures across the country, Republican lawmakers are introducing bills to curtail what educators–in public schools and universities–can say and teach about racism and sexism. Idaho Representative Ron Nate explained his sponsorship of a bill that was recently signed into law:

House Bill 377 is a great win for Idaho because it prohibits the promotion of Social Justice programming and advocacy for Critical Race Theory (CRT) in our schools and universities. CRT, rooted in Marxist thought, is a pernicious way of viewing the world. It demands that everything in society be viewed through the lens of racism, sexism, and power. . .

Rep. Nate said that this initiative “is only the beginning of removing the cancer of CRT from universities and preventing it from spreading into our K–12 education.”

This latest moral panic from the Right comes on the heels of recent legislation dangerously curtailing the rights of transgender people–especially young people–and enacting another round of voter suppression. It is paramount that we organize to defeat these threats to the health and safety of LGBTQ people, voting rights, and the freedom of educators to tell the truth. It is also worth reminding ourselves–and our students–of other times in U.S. history when powerful politicians manufactured threats and whipped up fear to neutralize progressive challenges to the status quo–the McCarthy Era being a well-known high-water mark of state repression.

Unfortunately, the version of this era that students get from mainstream textbooks obscures more than it instructs. Every high school textbook I consulted places the section on McCarthyism in its Cold War chapter and includes the following set pieces: Alger Hiss, the Hollywood Ten, and the Rosenbergs. It starts with a definition like “Anti-Communist attitudes and actions associated with Senator Joseph McCarthy in the early 1950s, including smear tactics and innuendo” (Pearson), closes with a heading like “McCarthy’s Fall” (National Geographic), and a final sentence about the man himself: “Joseph McCarthy, suffering from alcoholism, died a broken man” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).

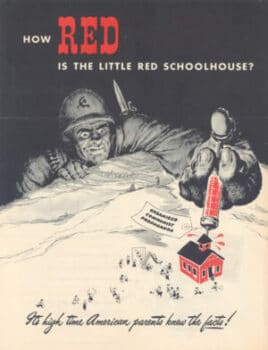

Contrary to this standard narrative, the “second Red Scare,” launched immediately following World War II, was a time when the government and powerful elites conspired to stamp out the efforts of some of the United States’ most dynamic activists and political organizations, like Sojourners for Truth and Justice, founded in 1951 by Louise Thompson Patterson and others. But repression of radical organizing in the United States was never confined to the so-called McCarthy era. Consider the attacks on radical activists like Emma Tenayuca, who led the 1938 San Antonio pecan shellers strike; and Hallie Flanagan, who headed the Federal Theater Project during the Great Depression. Whenever organizers challenged the status quo–racism, sexism, capitalism, militarism, and colonialism–its defenders screamed “communism.” Our students deserve to know that anti-communist repression has always been about a lot more than Russian spies, a blustering senator from Wisconsin, and a blacklist in Hollywood.

Understating the Scope

The textbook periodization of anti-communist repression, which posits the Red Scare in the years following World War I, and the second Red Scare in the late 1940s and early 1950s, erases the continuity and pervasiveness of anti-communist politics and policies throughout the 20th century. It suggests to students that anti-communist political repression was exceptional, tightly bound into two discrete decades. But between the Palmer Raids and McCarthy, there were the Fish Committee and the Dies Committee (HUAC), and after McCarthy there was COINTELPRO. Indeed, anti-communist persecution targeted the same people in more than one era.

Another problem is the term “McCarthyism” itself, which makes it virtually impossible not to overstate the centrality of Joseph McCarthy, the man. Textbooks show us photos of McCarthy at a map depicting communist infiltration of the military (National Geographic) and acknowledging the cheers of a crowd of flag-waving supporters (Glencoe). Textbooks tell us that “He drank too much and could get offensive and even violent at times. He was not well-liked; but he learned how to be feared” (Glencoe). Students walk away with a sense of McCarthy as a kind of boorish joke, so extreme and incompetent he might easily be dismissed as an outlier. That may be true of the man, but not of his politics. As historian David K. Johnson has written:

To attribute the purges to McCarthy serves to marginalize them historically. It suggests they were the product of a uniquely unscrupulous demagogue, did not enjoy widespread support, and were not part of mainstream conservatism or the Republican Party.

Activists James Jackson and Esther Cooper Jackson with daughters. Source: Cooper Jackson Family Collection

Erasing the Victims

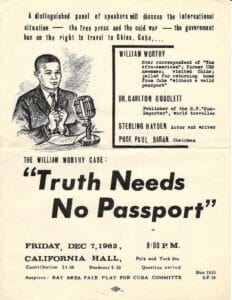

Not a single one of the McCarthyism sections in the five different middle and high school textbooks I consulted mentions anti-communist attacks on the civil rights movement or Black activists. Organizations like the Southern Negro Youth Congress and Sojourners for Truth and Justice were harassed out of existence by the government’s attacks. Even Paul Robeson, arguably the most famous target of the Red Scare’s attack on Black activists, shows up only in a chapter hundreds of pages removed from the one on McCarthyism, celebrating the “advances of African Americans on stage and screen” during the Harlem Renaissance (National Geographic). The textbooks give equal space–that is, virtually none–to other targets of anti-communist political persecution: radical labor unions, anti-war activists, feminists and LGBTQ people, Jews, and immigrants.

Dodging Politics

The words are repeated again and again in the textbook accounts of the Red Scare: communist and communism.

The Korean War reinforced the second Red Scare. . . . Legitimate concerns about espionage mixed with suspicions that Communist sympathizers in high places were helping Stalin and Mao. (Pearson)

The Soviet domination of Eastern Europe and the Communist takeover of China shocked the American public. These events fueled a fear that communism would spread around the world. (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

Astonishingly, four of the five textbooks I reviewed provide no definition of communism in the entire McCarthyism chapter.

For the most part, “communism” in textbooks is used in precisely the same way it was used by the anti-communist hatchet men: a kind of catch-all boogeyman, always dangerous and foreign (Mao! Stalin! China! Korea!) but never examined in the context of actual political struggles. For Claudia Jones, being a communist meant finding a way to organize against a racist criminal justice system that had recently sentenced eight Black teenagers to death for a crime they didn’t commit; for Louis Jaffe, a teacher in the radical New York City Teachers Union, communism meant working for the elimination of racist curricula and for well-resourced schools for even the city’s poorest children; and for Lorraine Hansberry, communism was a way to analyze the connection between the violence against Black Americans at home and the violence perpetrated by the U.S. military abroad, and a means to organize against both. For these activists, communism was not something foreign, but rooted in struggles for justice, at home and abroad. Were they to rely on their textbooks, students would have no way of knowing this arena of U.S. communist politics, since “communism” is siloed in a Cold War chapter, emphasizing foreign threats, and devoid of a single story of activists like those mentioned above.

Teaching the Red Scare

Paul Robeson, performer, and Charlotta Bass, newspaper editor, were both political activists targeted by Congress.

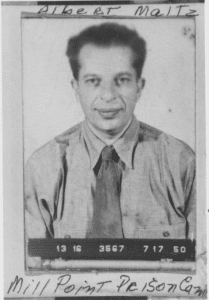

As a high school U.S. history teacher for 20 years, I struggled to find a good way to teach McCarthyism. So most of the time–I am embarrassed to admit–I skipped it altogether. “Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare” is a lesson I wish I had written earlier in my career. In it, students meet 27 different targets of government harassment and repression. Some are communists (or Communists), some are not. Most are politically engaged in some form of organizing, but not all. They are men and women, immigrants and native-born, young and old, racially diverse, in government and outside it, affluent, middle class, and poor, Queer and straight. Students analyze why these disparate individuals might have become targets of the same campaign. What kind of threat did they pose in the view of the U.S. government? And why do most textbooks leave them out?

The long Red Scare of the 20th century was a scorched-earth policy against the country’s most progressive forces–labor unions organizing across racial lines; civil rights organizations offering intersectional critiques of capitalism, racism, and gender oppression, generations before Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw coined that term; writers, artists, and journalists who advocated internationalism and peace. Red-baiting has not gone away, but it lacks the same destructive power it once had. When Sen. Ted Cruz slings the word “socialist” at one of his opponents, it may induce a little cortisol burst in his supporters. But in the minds of many younger people, “socialism” more likely evokes northern European nations with free college, universal health care, and paid family leave–not exactly the stuff of nightmares–than Stalinist Russia.

But it would be naive to conclude there is no cause for concern. When we look at the function McCarthyism served, it is not hard to find new discourses doing similar kinds of dirty work. Whereas “communist” became shorthand for any undesirable person or belief in the eyes of the elites, so today “voter fraud” is used by Republicans to disenfranchise “undesirable” voters who threaten to upset their traditional seats of power, and Critical Race Theory acts as a sweeping indictment of white supremacy’s critics. This lesson aims to help students become alert to the way shiny new terminology can advance very old forms of oppression.

Perhaps more importantly, the version of McCarthyism we offer our students should restore the powerful and inspiring stories of the activists and organizations who were its victims. The transformational social change needed in the United States and across the globe will never come from above, from presidents, CEOs, or billionaires. It will come from people like us, like our students–and like the many everyday people targeted by anti-communist repression. The Jack O’Dells, Esther Cooper Jacksons, Sam Wallachs, and Elizabeth Catletts. Although activists who call for abolition of prisons and police, or a complete moratorium on fossil fuel extraction, or a jobs guarantee for every American, are often dismissed as impractical, imprudent, and utopian, our students deserve to know there have always been savvy dreamers, clear-eyed critics of the status quo, who believe–and act like–a better world is possible.

Ursula Wolfe-Rocca has taught high school social studies since 2000. She is on the editorial board of Rethinking Schools and is a Zinn Education Project Writer and Organizer.