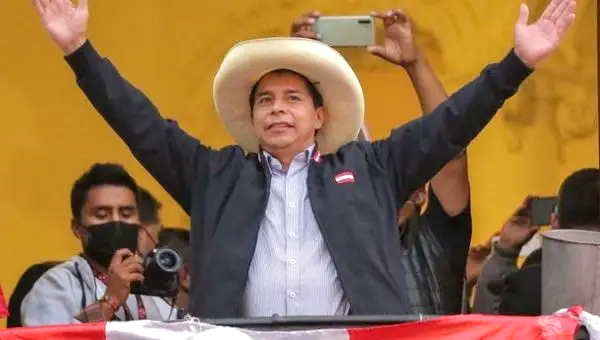

On June 10, 2021, the National Office of Electoral Processes (ONPE) published the results of the second round of elections to elect the new president of Peru, with the winner being Pedro Castillo, the candidate for the leftist party Peru Libre (PL). Castillo obtained 8,800,486 votes against the 8,730,712 garnered by his ultra-right opponent Keiko Fujimori of the Popular Force (FP). Fujimori–using the pattern followed by the political Right in Latin America–has raised allegations of irregularities and fraud in the electoral process. Her attempts to overturn the legitimate results are borne out of personal necessity.

Fujimori is facing a potential 30 years sentence, mainly for receiving illegal campaign money from some of the most powerful local business tycoons, including top bankers. During her political career, she’s been credibly connected to cocaine trafficking and corruption networks deeply embedded in different branches of the country’s government, among them the notorious “Cuellos Blancos” inside the judiciary. Winning the presidency would have stalled the criminal process against her for another five years. Now, she can’t run scot-free; the lead prosecutor in the corruption case has already requested preventive imprisonment for her.

Change in the Correlation of Forces

The victory of Castillo is an important one; it breaks the stasis within the country’s political framework. Peru held its previous presidential election in 2016, and has had four presidents since then: Martín Vizcarra replaced Pedro Pablo Kuczynski in March 2018 and was impeached by a hostile Congress in November 2020; his successor, Manuel Merino, lasted merely five days, amid popular uproar at Vizcarra’s ouster, and was replaced by Francisco Sagasti, a US-educated technocrat. The political elites of Peru had synthetically created an electoral vacuum where they remained cognizant of nothing other than their own opportunistic tactics. Congress had been largely reduced to an association of charlatans, mafia men, evangelical sects and robber barons.

The triumph of the Left has ushered in a new correlation of forces. Pedro Castillo, son of peasant farmers in the Chota province located in the Northern Andean region of Cajamarca, comes from the teachers’ union, the largest trade union in Peru, having between 300,000 and 400,000 members. Instead of trying to appeal to the elite in Lima, he ran a working-class campaign, intended to reach the impoverished communities of the rural areas. A post-neoliberal program has been put forward including state regulation of the market, state planning, nationalization of strategic sectors, improvement of tax collection through a progressive tax scheme, renegotiation of legal contracts with transnational capital, and controls over the repatriation of profits.

On the foreign policy front, Castillo has supported an anti-imperialist posture. In his first 100 days, he has promised to expel the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), a de facto U.S. intelligence operation masquerading as charity, and to close the U.S. military bases in the country, as well as to withdraw Peru from the Lima Group–the bloc of right-wing governments in the region established in Peru’s capital that have attempted to overthrow the socialist government of Venezuela.

A New Chapter in Peruvian History

The outcome of the 2021 presidential election also has historical importance, resetting a politico-economic trajectory primarily marked by elite dominance and a weak subaltern movement. The post-World War Two economic boom–characterized by a laissez-faire model–stabilized the economic power of the Peruvian elite. These free-market policies remained unquestioned till the 1960s. Thereafter, as exports slowed, interventionist strategies were introduced to stimulate growth. The 1959 Industries Law resulted in a minor tweak to the economy, but the manufacturing it promoted grew from a low base and was dominated largely by foreign investment, especially from the U.S.

The reformist Fernando Belaunde government (1963-1968) represented a break from the past and brought forth plans for economic diversification and land reform. However, it was only after Belaunde was deposed in the 1968 military coup that more full-fledged plans for modernization were initiated under General Juan Velasco Alvarado. Under his rule, the balance of forces changed in favour of the working class though it was a primarily top-down process of transformative change. The Velasco government (1968-1975) was radical. It implemented an agrarian reform that sought to break the power of the old agrarian oligarchy. Land was redistributed not only in the highlands but also in the far more productive coastal valleys where previously powerful interests resisted reform.

The government also began a series of nationalizations, targeting exploitative, foreign-owned interests, especially in mining, oil, and banking. State intervention in the economy increased substantially, and the political elites lost much of their control over the media oligarchies. The military government gave rise to an assertive movement. While it sought to regulate participation through institutional mechanisms like National System of Support for Social Mobilization (SINAMOS), radical energies quickly surpassed the state’s ability to maintain control. Socialist agendas gained hegemony in the rural sector (encouraged by the agrarian reform), in the manufacturing sector, and within rapidly growing squatter settlements on the peripheries of major cities. It was this growing social pressure that, in 1975, encouraged more conservative generals to seize power, remove Velasco, and end the state-led experiment.

The bourgeoisie quickly began recentralizing power through the paradigm of liberalization established by the military under General Francisco Morales Bermudez (1975-1980), and then by the civilian government of Belaunde (1980-1985). After the 1982 debt crisis, climate disasters, and the expansion of the guerrilla insurgency, Sendero Luminoso (SL) converged to disrupt the drive toward neoliberalization, Alan García (1985-1990) re-instituted a state-led approach. He attempted to reflate the economy by limiting payments to international creditors and boosting domestic demand. These measures resulted in hyperinflation and an economic collapse.

Fujimori’s father, Alberto, unleashed a liberalization package in 1990 with support from Washington and the international financial institutions (IFIs). It proved to be a ruthless neoliberal experiment, involving the privatization of nearly all public companies, a thorough deregulation of markets, the opening of Peruvian markets to unbridled imports, and the provision of inordinate incentives to foreign investment, notably in the key mining sector. Fujimori also restructured the political system after the autogolpe or self-coup of April 5, 1992, when he suspended the Peruvian Constitution of 1979, and dissolved Congress and the judiciary. From the autogolpe until the election of 2000, Fujimori ruled an increasingly corrupt and authoritarian government without any effective checks on his power. He is currently serving a prison sentence for corruption and human-rights abuses. He was also convicted of murder and kidnapping over the activities of anti-communist death squads like the Grupo Colina. As president, he presided over thousands of political killings and hundreds of thousands of forced sterilizations, mostly of Native American Quecha women, as part of efforts to solve “the Indian problem.”

The Left in Peru failed in resisting the neoliberal changes. The once electorally powerful United Left (Izquierda Unida) remained passive. Suffering serious internal splits, the Left failed to mount a serious alternative in the 1990s. Organized labour was ineffectual in countering the collapse in workers’ living standards of the late 1980s and suffered greatly from the subsequent privatization of public companies. The internal war with SL, meanwhile, destroyed the rural organization built by the Left in previous decades while giving rise to an issue that played into the hands of the right and helped consolidate the hegemony of Fujimori and the Right.

The return to democracy in 2000 did not lead to a change in the economic model. Under Alejandro Toledo (2001-2006), despite some democratic reforms, the neoliberal model remained firmly intact. Under García (2006-2011), it was further reinforced, particularly with respect to trade liberalization and the attraction of foreign investment. Ollanta Humala (2011-2016) came to power on the basis of opposition to neoliberalism but was swift in jettisoning heterodox policies on taking office. Taking into account the historical context, Castillo’s electoral success is unique because it symbolizes the popular defeat of the ruling class agenda.