Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Reminder: Indian peasants and agricultural workers remain in the midst of a country-wide agitation sparked by the proposal of three farm bills that were then signed into law by the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party government in September 2020. In June 2021, our dossier summarised the situation plainly:

It is clear that the problem in Indian agriculture is not too much institutional support, but inadequate and uneven deployment of institutions as well as the unwillingness of these institutions to address the inherent inequalities of village society. There is no evidence that agribusiness firms will develop infrastructure, enhance agricultural markets, or provide technical support to farmers. All this is clear to the farmers.

The farmers’ protests, which began in October 2020, are a sign of the clarity with which farmers have reacted to the agrarian crisis and to the three laws that will only deepen the crisis. No attempt by the government–including trying to incite farmers along religious lines–has succeeded in breaking the farmers’ unity. There is a new generation that has learned to resist, and they are prepared to take their fight across India.

In January 2021, the Supreme Court of India heard a series of petitions about the farmers’ protests. Chief Justice S. A. Bobde reacted to them with the following startling observation: ‘We don’t understand either why old people and women are kept in the protests’. The word ‘kept’ rankles. Did the Chief Justice believe that women are not farmers and that women farmers do not come to the protests of their own volition? That is the implication behind his remark.

A quick look at a recent labour force survey shows that 73.2% of women workers who live in rural areas work in agriculture; they are peasants, agricultural workers, and artisans. Meanwhile, only 55% of male workers who live in rural areas are engaged in agriculture. It is telling that only 12.8% of women farmers own land, which is an illustration of the gender inequality in India and is what likely provoked the Chief Justice’s sexist remark.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation pointed out a decade ago that ‘Closing the gender gap in agricultural inputs alone could lift 100-150 million people out of hunger’. Given the immense problem of hunger in our time–as highlighted in last week’s newsletter–women in agriculture must be, as the FAO notes, ‘heard as equal partners’.

Daniela Ruggeri (Argentina) / Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Childcare workers protest the Modi government’s unfair treatment of women and workers.

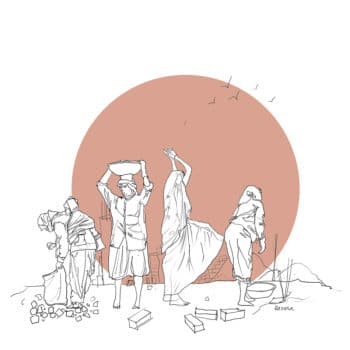

From Tricontinental Research Services (Delhi) comes a superb new dossier on the status of women in India, Indian Women on an Arduous Road to Equality (no. 45, October 2021). The text opens with an image of five women working at a brick kiln. When I saw that drawing, I was transported to a calculation made by Brinda Karat, a leader of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), about the labour of women construction workers. Bina, a young woman working in Ranchi, the capital of Jharkhand, carries between 1,500 and 2,000 bricks to masons in a multi-story building. Bina carries at least 3,000kgs of bricks every day, each weighing 2.5kgs, yet she earns a pittance of under ₹150 ($2) per day and suffers from severe body aches. ‘The pain has become an intrinsic part of my life. I don’t remember a single day without it’, Bina told Karat.

Reminder: Women in India have been an integral part of the farmers’ movement, the workers’ movement, and the movement to widen democracy. Does this need to be said? It seems that something so evident requires constant repetition.

During this pandemic, women public health workers and women childcare workers have played a central role in holding together society, all while being disparaged and having their work trivialised. On 24 September 2021, ten million scheme workers–those who work for government schemes such as public health (Accredited Social Health Activist or ASHA workers) and crèches (anganwadi workers)–went on strike to demand formal employment and better protection for their work during the COVID-19 pandemic. ‘Tax the super-rich’, they said, repeal the farm bills, stop the privatisation of the public sector, and defend women workers.

Over the past few years, ASHA workers have complained about routine harassment, including sexual harassment. In 2013, the Indian government enacted the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act to protect both formal and informal workers. No rules have been framed for ASHA and other scheme workers, nor are these workers able to lift up their experiences of harassment to the front pages of corporate media.

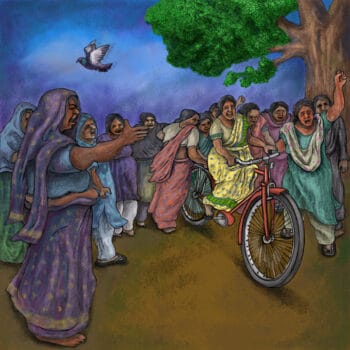

Vikas Thakur (India) / Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, A cycling training camp in Pudukkottai, Tamil Nadu.

Our dossier carefully dissects the prevalence of patriarchal harassment and violence, making sure to identify the different ways that such toxic behaviours strike at women of different classes. Working-class women in unions and in left organisations have built a kind of mass sensibility; as a result, their struggles now incorporate demands against patriarchy that had otherwise been distant from their lives. For instance, it is now clear amongst many working-class women that they must win maternity leave, equal wages for equal work, guaranteed crèches, and redressal and prevention mechanisms against sexual harassment in workplaces. Such demands cascade back into the family and community, where other struggles–such as against patriarchal violence in the home–expand the horizon of democratic movements in India.

The dossier closes with wise words about the importance of the farmers’ movement for the women’s movement:

Though the Indian women’s movement has seen many ups and downs over the decades, it has remained resilient, adapted to changing socioeconomic conditions, and even expanded. The current situation might present an opportunity to strengthen mass movements and to steer the focus towards the rights and livelihoods of women and workers. The ongoing Indian farmers’ movement, which started before the pandemic and continues to stay strong, offers the opportunity to steer the national discourse towards such an agenda. The tremendous participation of rural women, who travelled from different states to take turns sitting at the borders of the national capital for days, is a historic phenomenon. Their presence in the farmers’ movement provides hope for the women’s movement in a post-pandemic future.

Ingrid Neves (Brazil) / Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, A seaweed harvester facing the rough seas.

Reminder: Nothing in the slogans coming from the farmers’ encampments is unique. Most of these are long-standing claims. The demands made by women farmers at the protest sites and amplified by the farmers’ unions echo the Draft National Policy for Women in Agriculture put forward by the National Commission for Women in April 2008. This policy included the following key demands, each one applicable today:

- Ensure that women have access to and control over resources, including land rights, water, and pasture/forest/biodiversity resources.

- Guarantee equal wages for equal work.

- Pay minimum support prices to primary producers and ensure that sufficient food grains are available at affordable prices.

- Encourage women to enter agriculture-related industries (including fisheries and artisanal work).

- Provide training programmes for women including agricultural practices and technologies that are sensitive to the knowledge that women possess as well as the practices they carry out.

- Provide adequate and equal availability of services such as irrigation, credit, and insurance.

- Encourage primary producers to produce and market seeds, forest and dairy products, and livestock.

- Prevent women’s livelihoods from being displaced without providing viable alternatives.

The left women’s movement has put these demands back on the table. The right-wing government will not hear them.

Once more, our dossier comes to you designed with great care and love. This time, our team has worked closely with the Young Socialist Artists (India). Together, we found powerful photographs from the history of the Indian women’s movement and from the farmers’ protests and used these as references for the illustrations in the dossier. We look forward to inviting you to an online exhibition of this art, our small gesture towards expanding a possible pathway to a socialist future.

Warmly,

Vijay