Supposedly the highest praise one can bestow upon a work of nonfiction is to say, It reads like a novel. Yet this cliché insults both the genre of nonfiction and the experience of real life–as if life can’t yield sufficiently interesting events to hook a reader.

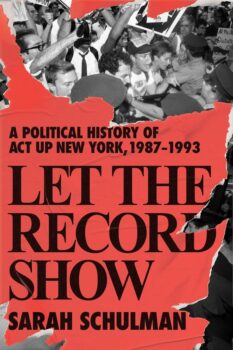

Still, Sarah Schulman brings to bear her experience as a novelist in Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT-UP New York, 1987-1993. The book is a riveting account of the founding chapter of the political direct action group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) in some of the most desperate years of the epidemic. Schulman has a keen eye for exactly which details bring a character to life and which beats to hit to turn even tangential anecdotes into engaging subplots.

Schulman also exercises her journalistic skills here, as she has been writing about AIDS since the early 1980s as a reporter for the New York Native. The book incorporates 188 interviews with surviving members of ACT-UP, analyzed and contextualized in a sweeping narrative. Oddly, the publisher is marketing the book as an autobiography; while Schulman’s participation and eyewitness are crucial, this label does the book a great disservice. If anything, Let The Record Show is a biography of the group, which was always far greater than merely the sum of its parts.

Yet Schulman’s experience as an activist–beyond her writing proficiency–is the ingredient that elevates this book from good story to essential movement primer. Schulman gives the reader an opportunity to learn from what ACT-UP New York did right and what they did wrong. While the group arguably shortened the AIDS epidemic–not to mention expanding the definition of AIDS itself–internal strife over access and tactics ultimately caused a painful rift. ACT-UP presaged and influenced modern movements from Occupy Wall Street to Black Lives Matter to the current struggle for LGBTQIA+ rights; in that light, Schulman provides not just a good read but a very useful one, particularly now.

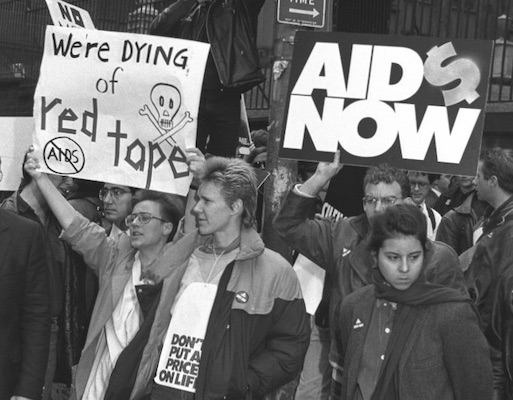

At its height, 800 people were regularly involved with ACT-UP New York. Over 7,000 people turned out for its biggest and most controversial action, disrupting the anti-gay and anti-AIDS-education Cardinal O’Connor during services at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. At ACT-UP New York’s founding in 1987, six years into the crisis, an estimated half-million Americans were living with HIV, yet President Ronald Reagan still hadn’t uttered the word AIDS. The New York chapter quickly inspired 148 autonomous chapters across the country and around the world.

ACT-UP New York had an anarchic framework, with big group meetings on Monday nights (usually at the LGBT Center, sometimes at Cooper Union) as well as many affinity groups and subcommittees who worked independently. While the group had some prominent figures, structurally it was leaderless. The book reflects that structure in its refreshing refusal to submit to the usual myth-making around AIDS activism, which often deifies a few white, gay male heroes and omits the rest. While lauded orator Larry Kramer did kick off the group with an incendiary speech, for example, he was involved only with certain specific projects, unaware of much of the other work happening in the multi-racial and multi-gendered organization. By contrast, Schulman stresses in the preface,

This is a book in which all people with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) or with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are equally important.

But indeed this argument over how to historicize AIDS activism reflects one of the major tensions in ACT-UP New York: whether to focus on the many or the few. Many in ACT-UP were white, gay men (often closeted) who enjoyed privilege until they seroconverted and were shocked to find out that the mainstream deemed their lives worthless; others were women and/or queers and/or people of color who had never had such illusions. For a while, this tension worked for the group, a sort of “good cop/bad cop” strategy. While some members met with Anthony Fauci and other such high-placed officials, focusing solely on rushing drugs into production (“drugs into bodies”), others took a wider view, fighting to protect the most vulnerable and to access healthcare for all. Ultimately, this conflict escalated to the point that the dozen members of the Treatment Action Guerillas split off in 1992 to become a 501(c)3 non-profit–but they were merely a small fraction of the hundreds of active members who remained.

Current activists have many lessons to learn from ACT-UP New York. Ironically, the group’s desperation led to great productivity, as lives were literally at stake and no one had time to waste. Instead of sitting around hashing out theory, their politics grew out of their actions, rather than the other way around. What’s more, the structure of independent committees enabled ACT-UP New York to tackle a wide variety of projects–everything from needle exchange to housing people with AIDS to queer youth organizing–without needing group consensus. Affinity groups strengthened bonds of solidarity and increased safety, enabling people to take risks like committing civil disobedience.

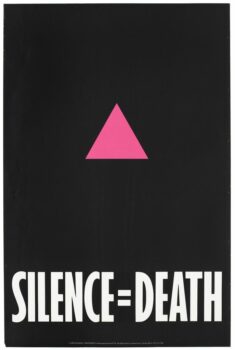

What’s more, ACT-UP New York made excellent use of the media, following the adage, “Don’t speak to the media; speak through the media”. They pioneered the tactic of video activism , using brand-new technology such as portable video cameras to document demonstrations, as well as police behavior–presaging people filming police misconduct on their phones. They created and preserved their own counterculture, everything from the newsmagazine Outweek to eye-catching art, most notably originating the now-ubiquitous “Silence = Death” branding.

What’s more, ACT-UP New York made excellent use of the media, following the adage, “Don’t speak to the media; speak through the media”. They pioneered the tactic of video activism , using brand-new technology such as portable video cameras to document demonstrations, as well as police behavior–presaging people filming police misconduct on their phones. They created and preserved their own counterculture, everything from the newsmagazine Outweek to eye-catching art, most notably originating the now-ubiquitous “Silence = Death” branding.

ACT-UP New York’s media savvy was driven by their delicious humor. For example, when Macy’s fired a man from playing Santa because he admitted to taking the AIDS drug AZT, 25 men of all colors and sizes dressed up in Santa costumes and chained themselves together in the cosmetics department. And the drag acapella choir Church Ladies for Choice enlivened many demonstrations, retooling “God Save the Queen” as “God Is a Lesbian” (“God is a lesbian/She is a lesbian/God is a dyke”).

But the group didn’t just help members hold onto their humor and sanity; it helped them make sense of the traumatic experience, especially as the straight world gaslit them, acting like the epidemic wasn’t happening. In that sense this book is not just a record but a validation, a crucial affirmation of a shared narrative.

Schulman concludes the book with an anecdote about her own health crisis, which her ACT-UP experience helped her manage. “AIDS prepared us for everything,” says her friend Jack Waters. Indeed it is impossible to read this book and not see glaring connections to the pandemic–the prominence of Dr. Anthony Fauci, the rush to put “drugs into bodies” and perhaps most importantly, the experience of thinking about health collectively rather than individually and realizing that protecting the most vulnerable raises the bar for everyone. AIDS and ACT-UP New York prepared us for this too.