When Pavel Zavalny, the chairman of Russian parliamentary committee on energy, made the forecast last Friday that Nord Stream 2 pipeline could start shipping natural gas to Germany as early as next month, it was received with disbelief. But Zavalny was categorical, and was quoted by Reuters as saying,

I can say with a high degree of certainty that the first gas via Nord Stream 2 will go in January.

He added that Europeans would not want to drag their feet with the certification process over Nord Stream 2 at a time when their storage levels of gas is so abysmally low.

But Zavalny was effectively contradicting the German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock who had stated only four days back previously that the certification process stood suspended “due to the existence of clear regulation in European law regarding the energy area on unbundling and other issues of the [company’s] structure.”

Expert opinion since then has been that the earliest the gas would flow through the new pipeline can be only by the second half of 2022, if at all.

Meanwhile, the lawmakers in the U.S. Congress have been demanding that Washington should simply kill the pipeline project. Baerbock has the reputation of being a proxy of the Americans and the general impression is that after the exit of Angela Merkel as chancellor, 40-year old Baerbock is determined to steer Germany toward a “tough” line on Russia.

Conceivably, the Kremlin wasn’t amused. The undersea Nord Stream 2 pipeline has been built at a cost of $11 billion. But the Kremlin kept its thought to itself. We now know why.

The data from German network Cascade shows that all Russian natural gas shipments to Germany through a major transit pipeline known as the Yamal-Europe transnational gas pipeline reversed direction today.

The Yamal-Europe transnational gas pipeline runs from northwest Siberia to Frankfurt-an-der-Oder in eastern Germany via Belarus and Poland. Last year, around one-fifth of all natural gas sent to Western Europe went via Belarus.

The flows through the Yamal-Europe pipeline dropped to 6% of its capacity on Saturday, 5% on Sunday, and fell to zero by today morning.

Plainly put, Russia has halted its gas exports to Germany and it also transpires that Gazprom, the system’s operator in Russia and Belarus, has booked no capacity for transiting natural gas to Germany for the near future, either.

Moscow’s explanation is that Gazprom prioritises domestic consumption within Russia over export of gas to foreign countries and temperatures have plummeted in Moscow and other large Russian cities this week. It is a plausible explanation.

However, this is happening at an inflection point when due to the winter cold and the restricted supply, European energy prices have soared. The prices in Europe spiked 7% on Monday and are surging. (here, here and here)

Pressure is building on Germany as its emergency reserves have dropped to a “historically low level” of below 60% last week for the first time in years.

Moscow is offering that if only licence is granted to operate Nord Stream 2, Gazprom will promptly begin additional supplies to meet Germany’s needs. In anticipation of the German regulator’s approval, Gazprom even filled the first of the two parallel pipes with so-called technical gas in October and the second started to fill up in December.

But Germany claims it is a stickler for rules and regulations and the Nord Stream 2, which is registered in Switzerland, must first restructure its operations to comply with the requirements of the German energy watchdog BNetzA and abide as well by relevant EU law and only then can the intricate approval process, which started in September and was suspended in mid-November, resume.

The BNetzA head Jochen Homann predicted on Dec. 16 that a decision on Nord Steam 2 “won’t be made in the first half of 2022.”

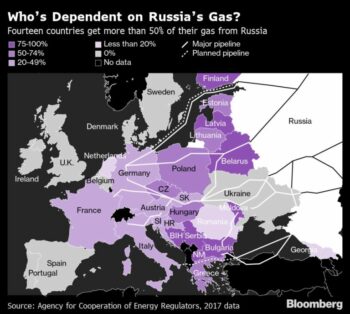

The bottomline is that while all protagonists pretend that this is a commercial issue, the U.S. has transformed it as a geopolitical issue. Simply put, the U.S. abhors the very idea of Russia consolidating its presence further in the European energy market and wants to kill Nord Steam 2 in its cradle.

The bottomline is that while all protagonists pretend that this is a commercial issue, the U.S. has transformed it as a geopolitical issue. Simply put, the U.S. abhors the very idea of Russia consolidating its presence further in the European energy market and wants to kill Nord Steam 2 in its cradle.

Second, Washington worries (rightly so) that such heavy German dependence on Russian energy will inevitably soften up Berlin’s attitudes toward Moscow in general, which will be detrimental to the interests of the transatlantic alliance.

Third, Washington wants Ukraine to continue to be the beneficiary of the transit fee of over 1 billion dollar annually which Gazprom was paying to Kiev for use of the Soviet-era pipelines passing through that country to western Europe. That is to say, while works systematically to turn Ukraine as an anti-Russian state, it expects Moscow to keep subsidising Ukrainian economy which is a basket case.

Finally, the U.S. hopes to make inroads into the lucrative European market for its own shale gas exports. In a long term perspective, the U.S. wants Europe to be dependent on its energy exports, just as NATO is its captive market for arms exports.

The new German government has walked into the American trap. By acting tough on Russia, Berlin forfeits Russia’s goodwill. The recent expulsion of two Russian diplomats posted to Berlin on dubious grounds most likely put Russia’s back up further. The German ministers have lately been speaking harshly about Russia in the context of Moscow’s tensions with NATO and the U.S.

Germany has played a double role on Ukraine running with the hare and hunting with the hounds. On the one hand, it played the role of a peacemaker along with Russia in the Normandy Four format (France, Germany, Ukraine, Russia) while at the same time secretly encouraging Kiev to be recalcitrant in the Donbas situation.

Moscow recently exposed Germany’s perfidious role by releasing its diplomatic correspondence with Berlin.

As the winter sets in and Germany’s energy requirements increase, it a shortage of gas can be expected in the coming weeks. The European continent may face rolling blackouts if the winter is cold. The price of gas will go through the roof, which will hit the consumers and German industry.

Moscow only can come to Germany’s and Europe’s rescue in these dire circumstances by exporting more gas via existing pipelines. But Gazprom linking it to clearance for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which it has constructed at heavy cost.

The catch is, the new German chancellor Olaf Scholz went one significant step further than Merkel and has agreed, pushed by Washington , to “consider” stopping Nord Stream 2 if Russia invades Ukraine (according to the FT).

German politicians ultimately pay heed to the captains of industry. Forty-year old Baerbock from the Green Party happens to be a greenhorn. Scholz, a conservative social democrat, has a lot of experience with political top jobs, albeit lacking in charisma and often underestimated.

In foreign policy, the buck stops at the Federal Chancellery–and Scholz stands for continuity in foreign policy so that he can focus on the German economy in pandemic times. Zavalny may have a point.