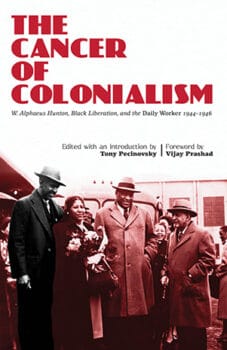

The Cancer of Colonialism: W. Alphaeus Hunton, Black Liberation and the Daily Worker 1944-46. Edited with an Introduction by Tony Pecinovsky. Foreword by Vijay Prashad. New York: International Publishers, 2021. 353pp, $19.99.

This highly unusual book highlights a forgotten journalist and thinker, but just as much, the assiduous research and interpretations by Tony Pecinovsky, a St. Louis activist and non-academic scholar, on the history of the U.S. Left. W.A. Hunton, to quote W.E.B. Du Bois, was “the kind of absolutely honest and unselfish scholar who is apt to be trampled on and neglected in the present American world.” (p.177) Thanks to Pecinovsky, Hunton is rediscovered.

The crucial argument here, that the immediate post-World War II years offered a leap of human liberation turned back through repression, has been fortified by global scholarship in the last several decades. The framing of those years as the U.S. versus Russia was itself an invention of sorts, a way for the emerging world system directed from Washington (and Wall Street) to deflect the larger and more complex but also vastly more promising alternative. The Global South was stirring, finding its own way, if only it could the freedom of choices that it needed.

This is a vital memory to recover, because it has been so effectively buried or, amidst so much else in the receding past, simply misplaced and forgotten. The English-speaking Caribbean, to offer one example, seemingly buried the memory of region-wide strikes and uprisings during the middle and late 1930s underneath the saga of the world war and. the dramatic effects of U.S. military occupations, urbanization, new jobs and social patterns. As the War ended, thousands hungered for the independence and social justice articulated in struggle less than a decade earlier. The victories of the Red Army in Europe, along with colonial restlessness across the globe, offered brilliant hopes. The more conservative Caribbean leaders put their thumbs down on the promising and popular World Federation of Trade Unions, quashing labor radicalism., Leadership of the struggling independence movements passed to other hand. A moment lost, justice denied and delayed: in some ways, despite future independence for the islands, that moment never returned.

The CPUSA, struggling with a myriad of social issues at home and abroad, not to mention internal turmoil, attracted writer-activists with a brilliant grasp of the details in the unfolding world scene. None proved themselves more lucid than W. Alphaeus Hunton. Born in the South in 1903 but raised in Brooklyn, an activist and supporter of the Communist Party from early age, Hunton graduated from Howard and went on to New York University, returning to Howard as an English teacher and helping to launch a union for faculty members members there. He continued work on a PhD, taking the degree at Harvard in 1938.

By that time, Hunton had become active in the National Negro Congress, an effective mass movement or united front that Communists had worked to create and that Hunton, as Pecinovsky suggests, hoped to emulate for the rest of his political life. Thanks in no small part to and NNC and to Hunton himself, the creation of the Southern Negro Youth Congress, founded in 1937, more than extended the work of the NNC. With more than a hundred locals, the SNYC extended the influence of the NNC notably in the extremely difficult conditions of the South.

The happiest part of this journey ended early, even as Hunton organized the third convention of the NNC in 1940. McCarthyism, launched by Congressional investigating committees before anyone heard of Joe McCarthy, threatened systematic repression. A cautious A. Philip Randolph, heretofore a vital ally, separated himself from the Popular Front Left and became a formidable enemy.

As FBI agents trailed Hunton, worse was to come. Meanwhile, he became educational director of the new Council on African Affairs, promoting the anticolonial struggle in every venue available. He was widely and proudly considered “Paul Robeson’s right hand man.” From the high perch of accredited UN observer in 1948, he descended, fighting all the way, struggling against the waves of repression. In charge of the CAA bail fund, unwilling to turn over the names to Congressional investigators, he served six months in federal prison.

Pecinovsky is rich in the details of Hunton’s Pan African work of the 1950s. Determined, along with many other Black members of the CP, to regard Khruschev’s repudiation of Stalinism in 1956 as a sign of socialist renewal, they soldiered on. Perhaps we might add, with a score of my own Old Left interviewees, that even many veteran Communists sufficiently disappointed in the Soviet Union to leave the CPUSA itself nevertheless continued to honor the Russian role in supporting anti-colonial struggles of the day. Thereby, they provided support of their own kind to those who remained with the organization.

Hunton would go on, undaunted, eventually shifting his personal locus to Ghana, so as to assist W.E.B. Du Bois in the creation of an Encyclopedia Africana. Expelled after the fall of Nkrumah, he died in Zambia in 1970.

Pecinovsky devotes the final 160 pages of this volume to excerpts from Hunton’s writings in the Daily Worker at the crucial moment of 1945-46. The subjects are mainly the hopes for Africa and the dangers posed by the brute strength of imperialism. Hunton supports the views of the Soviet Union on de-colonization, but his main effort is to explain to an audience little aware of such details, the meaning of the great events shaking and shaping the struggles for Black freedom.

The acuity of Hunton’s insights, seen in retrospect so many decades later, offers astounding reading. He takes on FDR’s prospective post-war policies on Africa and the Middle East, the prospects for the “mandated territories” promised independence but under the continued influence of the colonizers, the significance of the UN conferences, the plans of the U.S. for military bases, the hopes for China, and many others. Throughout, he has one clear aim: to let the peoples of the struggling masses in the emerging nations seize their own destiny.