In this study, Éric Toussaint covers the period from the 15th to the 21st century, focusing on the dramatic effects of capitalist globalisation.

The beginning of Globalization goes back to the outcomes of the first voyage of Christopher Columbus that brought him, on October 1492, to the shore of an island in the Caribbean Sea. [1] It was the starting point of a brutal and bloody intervention of European sea powers in the history of American peoples, a region of the world that had, up to then, remained insulated from regular relationships with Europe, Africa and Asia. The Spanish conquistadors and their Portuguese, British, French and Dutch counterparts [2] together conquered the whole geographical area, commonly known as the Americas [3], by causing the death of the vast majority of the indigenous population in order to exploit the natural resources (in particular gold and silver) [4]. Simultaneously, European powers started the conquest of Asia. Later on, they completed their domination in Australia and finally Africa.

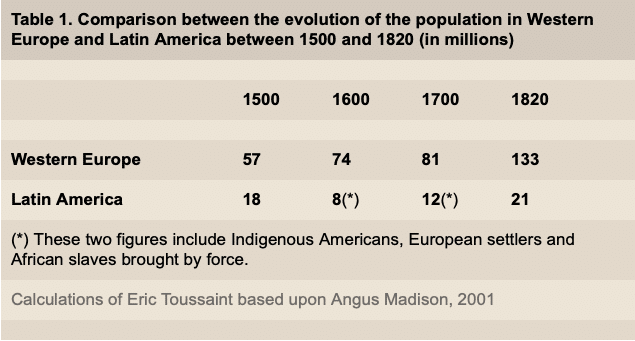

In 1500, just at the beginning of the brutal intervention of the Spaniards and the Portuguese in Central and South America, this region had at least 18 million inhabitants (some authors put forward much larger figures of close to 100 million [5]). One century later, only around 8 million inhabitants were left (including European settlers and the first African slaves). In the case of most islands of the Caribbean Sea, the whole indigenous population had been wiped out. It is worth recalling that during a long period of time, Europeans, supported by the Vatican [6], did not consider indigenous people from the Americas as human beings [7]. A convenient justification for exploitation and extermination.

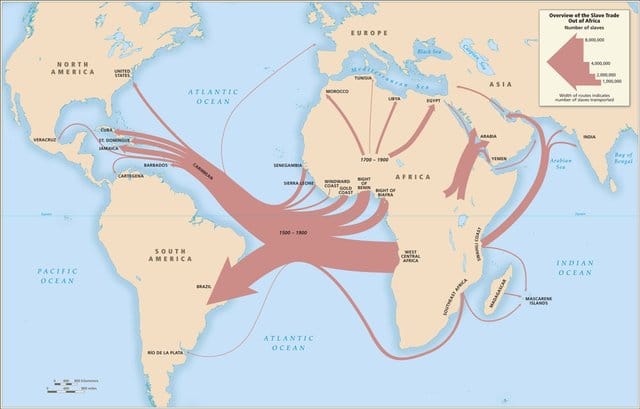

In North America, the European colonization started during the 17th century, mainly led by England and France, before undergoing a rapid expansion during the 18th century, an era also marked by massive importation of African slaves. Indigenous populations were either wiped out or driven outside the settlement zones of European settlers. In 1700, the indigenous population constituted three-quarters of the population; in 1820, their proportion had dropped down to 3%.

In North America, the European colonization started during the 17th century, mainly led by England and France, before undergoing a rapid expansion during the 18th century, an era also marked by massive importation of African slaves. Indigenous populations were either wiped out or driven outside the settlement zones of European settlers. In 1700, the indigenous population constituted three-quarters of the population; in 1820, their proportion had dropped down to 3%.

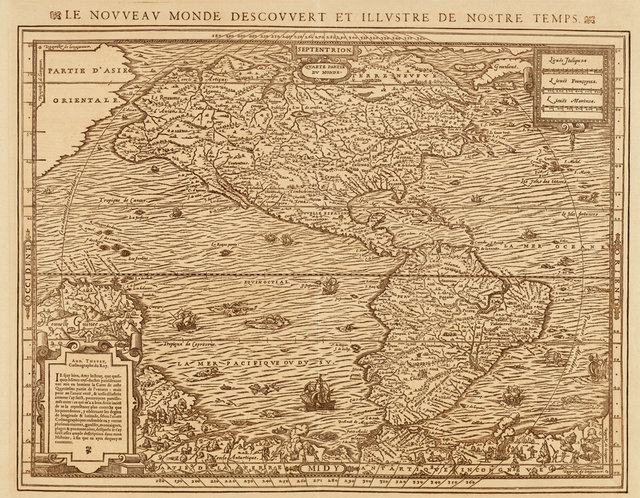

Until the forced integration of the Americas in global commerce, the main axis of intercontinental trade exchanges involved China, India and Europe [8]. Trade between Europe and China followed terrestrial and maritime routes (via the Black sea) [9]. The main route linking Europe to India (whether from the state of Gujarat in North-West India or from Kerala and the Calicut or Cochin harbours in the South-West) passed through the Mediterranean Sea, Alexandria, Syria, the Arabian Peninsula and finally the Arabian Sea. India also played an active role in trade exchanges between China and Europe.

Until the 15th century, technical progress achieved in Europe relied upon technology transfers from Asia and the Arab world.

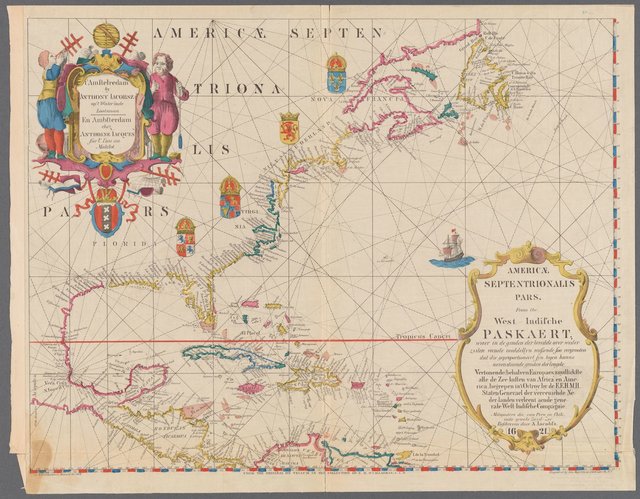

At the end of the 15th century and during the 16th century, trade started to follow other routes. When the Genoese, Christopher Columbus, serving under the Spanish crown, opened the maritime route towards the “Americas” [10] by sailing west through the Atlantic, the Portuguese sailor, Vasco da Gama, made for India, also through the Atlantic but heading south. He sailed along the Western coasts of Africa from North to South, veering East after crossing the Cape of Good Hope in the south of Africa [11].

Ferdinand Magellan is known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the East Indies across the Pacific to open a maritime trade route in which he discovered the interoceanic passage bearing thereafter his name and achieved the first European navigation from the Atlantic to Asia. This expedition, where Magellan was killed in the Battle of Mactan (present-day Philippines) in 1521, resulted in the first circumnavigation of the Earth when one of the expedition’s two remaining ships of five eventually returned to Spain in 1522.

Violence, coercion and robbery were central to the methods employed by Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama and Ferdinand Magellan to serve the interests of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns. During the following centuries, European powers and their servants would systematically use terror, extermination and extortion, combined with the search for compliant local allies. Several peoples worldwide would witness the brutal deviation of their history’s course under the whips of the conquistadors, settlers and European capital. Other peoples would suffer from an even more terrible fate since they were wiped out or reduced to the situation of foreigners in their own countries. Still, others were uprooted by force from one continent to another to serve as slaves.

Admittedly, prior to the 15th century of the Christian era, history had been marked on several occasions by conquests, dominations and barbarity without however touching the whole planet. What is striking of the last five centuries is that European powers started conquering the whole world and, within three centuries, interlinked (almost) all peoples of the world through brutal ways. During the same time, the capitalist logic finally succeeded in dominating all other modes of production (without necessarily eliminating them entirely).

Second intercontinental voyage of Vasco de Gama (1502)

Lisbon – Cape of Good Hope – Eastern Africa – India (Kerala)

50 Escudos celebrating the quincentennial of Vasco Da Gama, 1969 by cgb is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

After the first voyage to India in 1497-1499, Vasco da Gama was again assigned by the Portuguese crown to return there with a fleet of twenty ships. He left Lisbon in February 1502. Fifteen ships would have to come back while five (under the command of da Gama’s uncle) would stay behind, both to protect Portuguese bases in India and to block ships leaving towards the Red Sea, thus shutting off trade between the two areas. Da Gama rounded the Cape in June, stopping in Sofala, East Africa, to buy gold [13]. In Kilwa, he forced the local sovereign to make an annual payment of pearls and gold before making for India. Off Cannanore (70km north of Calicut – today Kozhikode), Da Gama waited for Arab ships returning from the Red Sea, to seize a ship, on the route from Mecca, with pilgrims and valuable cargo. Part of the cargo was seized and the ship set on fire, resulting in the death of most of its passengers and crew. The next stop was Cannanore where he swapped gifts (gold for precious stones) with the local sovereign without making business, estimating that the price of spices was too high. He sailed for Cochin (today Kochi), stopped his ships in front of Calicut and asked the sovereign to expel the whole Muslim trading community (4000 households) who used the harbour as a base for commerce with the Red Sea.

At the end of the 15th century, capitalist commercialization of the world received the first boost, subsequently followed by others, namely the 19th-century diffusion of the industrial revolution from Western Europe and the “late” colonization of Africa by the European powers. The first international economic crisis (in industry, finance and trade) exploded at the beginning of the 19th century, leading to the first debt crises [12]. The 20th century has been the scene of two World Wars, with Europe as their epicentre, and unsuccessful attempts to implement socialism. In the seventies, the turn of global capitalism towards neo-liberalism, and the restoration of capitalism in the former Soviet block and China have provided a new boost to globalization.

Following the Samudri’s (local Hindu sovereign) refusal, Vasco da Gama ordered the bombardment of the town, following in the footsteps of another Portuguese sailor, Pedro Cabal, in 1500. He set for Cochin at the beginning of November where he bought spices in exchange for silver, copper and textiles stolen from the sunken ship. A permanent trading post was established in Cochin and five ships were left there to protect Portuguese interests.

Before leaving India for Portugal, Da Gama’s fleet was attacked by more than thirty ships financed by Calicut Muslim traders. A Portuguese bombardment led to their defeat. Consequently, a part of Calicut’s Muslim trading community decided to base their operations elsewhere. Those naval battles clearly demonstrate the violence and criminal nature of the action of Vasco da Gama and the Portuguese fleet.

Da Gama returned to Lisbon in October 1503 with thirteen of his ships and approximately 1700 tons of spices, that is, around the same amount imported from the Middle East at the end of the 15th century by Venice. Portuguese profit margins from this trade were much larger than those of Venetians. A major part of the spices was sold in Europe via Antwerp, the major harbour of the Spanish Netherlands, then the most important European harbour.

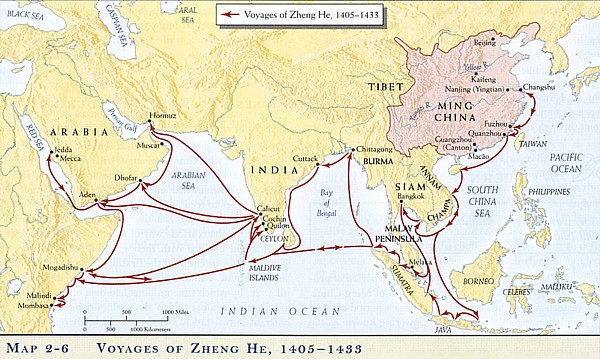

Maritime Chinese expeditions during the 15th century

Europeans were not the only ones travelling far away and discovering new maritime routes. But they were the most aggressive and the most conquering.

Several decades before Vasco da Gama, between 1405 and 1433, seven Chinese expeditions headed West and notably visited Indonesia, Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, the Arabian peninsula (the Strait of Ormuz and the Red Sea), the Eastern Coast of Africa (notably Mogadishu and Malindi).

Under Emperor Yongle, the Ming marine “included approximately a total of 3800 ships, among which were 1350 patrol boats and 1350 battleships incorporated into defence or insular bases, the main fleet of 400 heavy battleships stationed near Nanking and 400 loading ships for cereal transportation. Moreover, there were more than 20 treasure-boats, ships equipped to undertake large scale action“ [14]. They were five times larger than any ship of Da Gama, 120 meters long and nearly 50 meters wide. The large boats possessed 15 watertight compartments so that a damaged ship would not sink and could be repaired at sea.

Their intentions were pacifist but their military force was sufficiently imposing to fend off attacks that only took place three times. The first expedition aimed towards India and its spices. Others were geared towards exploring the Eastern Coast of Africa, the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf.

The main goal of these voyages was to establish good relationships by offering gifts and escorting ambassadors or sovereigns that were coming to or leaving China. No attempt was ever made to establish bases for trade or military purposes. The Chinese were looking for new plants for medicinal needs and one of the missions comprised 180 members of the medical profession. In contrast, during the first voyage of Vasco da Gama to India, his crew included approximately 160 men, among whom were gunners, musicians and three Arab interpreters. After 1433, the Chinese abandoned their lengthy maritime expeditions and gave priority to internal development.

In 1500, standards of living were comparable

When, at the end of the 15th Century, Western European powers launched their conquests of the rest of the world, European standards of living and level of development were no higher than those of other large areas of the world. China was unquestionably ahead of Western Europe in many ways: in people’s living conditions, in the sciences, infrastructure [15] and agricultural and manufacturing processes. India was more or less on a par with Europe, as far as living conditions and quality of manufactured goods were concerned (Indian textiles and iron were of better quality than European products) [16]. The Inca civilization in the Andes in Southern America and the Aztecs in Mexico were also flourishing and very advanced.

We should be cautious when defining criteria for measuring development and avoid limiting ourselves to the calculation of GDP per capita. Having said that, even if we take this measure and add life expectancy and quality of food available, the Europeans did not live any better than the inhabitants of other large areas of the world, prior to their conquering expeditions.

Intra-Asian trade before the European powers burst onto the scene

In 1500 Asia’s population was five times that of Western Europe. The Indian population alone was twice that of Western Europe. Hence, it represented a very large market, with a network of Asian traders operating between East Africa and Western India, and between Eastern India and Indonesia. East of the Malacca Straits, trade was dominated by China.

Asian traders knew the seasonal wind patterns and navigation hazards of the Indian Ocean well. There were many experienced sailors in the area, and they had a wealth of scientific literature available on astronomy and navigation. Their navigation tools had little to envy those of the Portuguese.

From East Africa to Malacca (in the narrow straits separating Sumatra from Malaysia), Asian trade was conducted by communities of merchants who did their business without armed gunships or heavy government intervention.

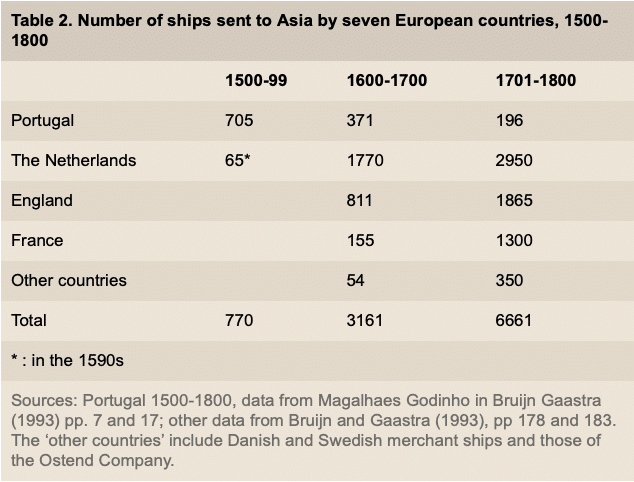

Things changed radically with the methods used by the Portuguese, Dutch, English and French, serving state and merchant interests. The maritime expeditions launched by the European powers to various parts of Asia increased considerably, as shown in the table below (from Maddison, 2001). It shows clearly that Portugal was the indisputable European power in Asia in the 16th Century. The following century it was replaced by the Dutch, who remained dominant throughout the 18th Century, and the English were in second place.

Great Britain joins the other European powers in the conquest of the world

In the 16th Century, England’s main occupations outside Europe were piracy and reconnaissance trips to explore the possibility of setting up a colonial empire. The most daring act was the royal support given to Drake’s (1577-80) expedition which, with five ships and 116 crew, rounded the Strait of Magellan, captured and plundered the treasure-laden Spanish ships off the Chilean and Peruvian coasts, set up useful contacts with the spice islands of the Molucca Sea, Java, Cape of Good Hope and Guinea on the way home[17].

At the end of the 16th Century, Great Britain scored the decisive victory which sealed its status as a naval power when it defeated the Spanish Armada off the British coast.

From that moment on, Britain plunged into the conquest of the New World and Asia. In the New World it set up sugar-producing colonies in the Caribbean and, from the 1620s on, was an active participant in the trading of slaves imported from Africa. Simultaneously, between 1607 and 1713 it set up fifteen colonies of settlement in North America, thirteen of which ended up declaring their independence and becoming, in 1776, the United States, while the other two stayed within the British circle and were to become part of Canada.

In Asia, the British crown adopted a different policy: rather than settler colonies, it set up a system of exploitation colonies, starting with India. To this end, the British state granted its protection to the East India Company (an association of merchants in competition with other similar groups in Great Britain) in 1600. In 1702 the State bestowed a trade monopoly on the East India Company and threw itself into the fight for the subcontinent, which ended with the British victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, giving them control of Bengal. For a little over two centuries, Great Britain applied an uncompromising protectionist economic policy, and once it had become the dominant economic power during the 19th Century, it imposed an imperialist free-trade policy. For example, with the help of gunboats, it imposed ‘free trade’ on China, forcing the latter to buy Indian opium while allowing the British to buy Chinese tea for resale on the European market with the proceeds of the opium sales.

Elsewhere, Britain extended its conquests in Asia (Burma, Malaysia), in Australasia (Australia, New Zealand…), in North Africa (Egypt), and in the Near East.

As for sub-Saharan Africa, until the 19th Century, its only major interest was the slave trade. Later on, the conquest of Africa became an objective.

Goa: a Portuguese enclave in India

In India, as in other parts of Asia, the English had been preceded by the Portuguese, who conquered small parcels of Indian Territory. They set up trading posts and installed religious terrorism. As such, an Inquisition court was set up in Goa in 1560, which imposed its cruelty until 1812. In 1567, all Hindu ceremonies were banned. In just over two centuries, sixteen thousand sentences were pronounced by the Goa Inquisition and thousands of Indians were burnt at the stake.

The British Conquest of the Indies

The British, in their conquest of India, expelled their other European rivals the Dutch and the French. The latter was determined to prevail, but they could not do so. Their defeat in the Seven Years War against the British was mainly due to insufficient support from the French state [18].

To take control of India, the British systematically sought out allies amongst the local rulers and ruling classes. They did not hesitate to use force, when deemed necessary, as in the Battle of Plassey in 1757 and the violent repression of the Sepoy Rebellion in 1859.

They bent the local power structures to their service and generally left the local lords in place, allowing them to continue to lead an ostentatious life although the rules of the game were dictated by others (they were powerless against the British). The division of society into castes was maintained and even reinforced, which still weighs heavily on today’s India. In effect, the division of society into classes and gender domination were reinforced by a division into castes, based on birth.

Through taxation and unfair terms of trade between India and Great Britain, the Indian people contributed to the enrichment of Britain both as a country and in terms of its rich classes (merchants, industrialists and politicians). But the British are not the only ones who got rich: bankers, merchants and Indian manufacturers also accumulated immense fortunes. Thanks to them, the East India Company (EIC) and the British state managed to exert, for such a long time, domination which the people profoundly rejected.

The example of the cotton industry

The quality of textiles and cotton produced in India was unrivalled anywhere in the world. The British tried to copy the Indian production techniques and produce cotton of comparable quality at home, but for a long time, the results were quite poor. Under pressure, particularly from the owners of British cotton mills, the British government prohibited the export of Indian cotton to any part of the British Empire. London further forbade the East India Company to trade Indian cotton outside the Empire, thus closing all possible outlets for Indian textiles. Only thanks to these measures were Britain able to make its own cotton industry really profitable.

Today, while the British and other industrialized powers systematically apply the Intellectual Property Rights Treaty (Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights – TRIPs) within the World Trade Organization, to demand payments from developing countries such as India, less than three centuries ago they had no qualms about copying Indian production methods and design, specifically in the textiles field. [19]

Furthermore, to increase their profits and become more competitive than the Indian cotton industry, the British owners of cotton companies decided to introduce new production techniques: steam-powered machinery and new looms and spinning machines. Through the use of force, the British fundamentally changed India’s development. Whereas up to the end of the 18th Century, the Indian economy exported high quality manufactured goods and could satisfy most domestic demands, in the 19th and 20th Century it was invaded by European products, particularly from Britain. Great Britain prevented India from exporting its manufactured goods, forced it to export increasing quantities of opium to China in the 19th Century (just as it coerced China to buy the opium) and flooded the Indian market with British manufactures. In short, it produced under-development in India.

The destruction and grabbing of collective commons

Since the dawn of capitalism the logic of collective commons has been systematically challenged by the capitalist class through commodification and private appropriation of wealth. One of their earliest objectives, when factories started to appear in Europe just over several centuries ago, was to take away the common people’s resources and livelihoods by grabbing the lands they lived on and so force them to migrate to the cities and accept the miserable and miserably paid jobs in the factories. On farther continents under European domination, their goal had been to grab the land and resources of local populations and force them into hard labour under the whip of imperialist exploiters.

From the 16th to the 19th century the various countries that one after the other fell under the yoke of capitalism all went through vast periods of the destruction of collective commons, a process that has been well documented by such authors as Karl Marx (1818-1883) Volume 1 of Capital, [20] Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919) in The Accumulation of Capital, [21] Karl Polanyi (1886-1964) The Great Transformation, [22] Silvia Federici (1942) Caliban and the Witch. [23] A great film by Raoul Peck The Young Karl Marx [24] visualizes examples of the destruction of collective commons with dramatic scenes of the brutal repression of poor people collecting wood for fuel in German Rhineland forests and Karl Marx’s stand in support of their centuries-old legal and traditional right to do so that was running contrary to capitalistic logic. Daniel Bensaïd has devoted a small book to this subject entitled The Dispossessed: Karl Marx’s Debates on Wood Theft and the Right of the Poor in which he shows the continuing process of destruction of the commons. [25]

In Capital, Karl Marx describes certain forms of grabbing by the capitalist system in Europe:

The spoliation of church properties, the fraudulent alienation of the State domains, the robbery of the common lands, the usurpation of feudal and clan property, and its transformation into the modern private property under circumstances of reckless terrorism, were just so many idyllic methods of primitive accumulation. They conquered the field for capitalistic agriculture, made the soil part and parcel of capital, and created for the town industries the necessary supply of a “free” and outlawed proletariat. (Capital, Volume I, eighth section. Chap. 27 www.marxists.org )

While capitalist production was being imposed on Europe it was also spreading all over the globe:

The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signalised the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief momenta of primitive accumulation. (Capital, Volume I, part 8. Chap. 31 www.marxists.org )

External debt as a means of domination and subordination

Throughout the 19th century, domination through external debt was a significant part of the imperialist policy of the major capitalist powers and it continues to plague the 21st century in new forms. As a fledgling Nation during 1820-1830, Greece capitulated to the dictates of creditor powers (especially Britain and France). [26] Though Haiti was liberated from France during the French Revolution and proclaimed its independence in 1804, debt again enslaved it to France in 1825. [27] France invaded indebted Tunisia in 1881 and turned it into a protectorate. [28] Great Britain led Egypt to the same fate in 1882. [29] From 1881, the Ottoman Empire’s direct submission to its creditors (Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy and others), [30] stepped up its disintegration. In the 19th century, creditors forced China to grant territorial concessions and to fully open up its market. The heavily indebted Tsarist Russia may also have become prey of creditor powers, had the Bolshevik revolution (1917-18) failed to repudiate the debt unilaterally.

During the second half of the 19th century different peripheral powers [31] – i.e. the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, the Russian Empire, China and Japan – had the potential to become imperialist capitalist powers. Only the last succeeded. [32] In fact, Japan had almost no recourse to external debt for its noteworthy economic development on its way to becoming an international power in the second half of the 19th century. Japan carried out a significant autonomous capitalist development following the reforms of the Meiji period (introduced in 1868). It imported the most advanced western production techniques prevailing at that time, prevented foreign interests from making financial inroads into its territory, rejected external loans and eliminated interior obstacles to the movement of indigenous capital. At the end of the 19th century, Japan transformed from a secular autocracy to a robust imperialist power. The absence of external debt was not the only reason why Japan became a major imperialist power through vigorous capitalist development and an aggressive foreign policy. Other factors equally mattered but they are too many to catalogue here. However, the lack of external debt evidently played a fundamental role. [33]

On the contrary, while China surged ahead with its impressive development until the 1830s to become a leading economic power, [34] its recourse to external debt allowed the European powers and the U.S. to gradually marginalize and control it. Again, other factors were involved, such as wars launched by Britain and France to impose free trade in China and force the country to import opium. However, external debt and its damaging consequences still played a vital role. In fact, China had to grant land and port concessions to foreign powers so that it could repay its external commitments.

Rosa Luxemburg wrote that one of the methods used by the Western capitalist powers to dominate China was “Heavy war contributions” which “necessitated a public debt, China taking up European loans, resulting in European control over her finances and occupation of her fortifications; the opening of free ports was enforced, railway concessions to European capitalists extorted.” [35] Nearly a century after Rosa Luxemburg, Joseph Stiglitz took up the issue in his book Globalization and Its Discontents.

External debt and free trade

During the first half of the 19th century, all Latin American governments except Francia’s Paraguay adopted free trade policies under pressure from Britain.

Since the local ruling classes did not invest in processing or manufacturing activities for the domestic market, the implementation of free trade did not threaten their interests. Consequently, free import of mainly British manufactured goods hindered the development of these countries’ industrial fabric. The abandonment of protectionism destroyed a large part of the local factories and workshops, particularly in the textile sector.

In a way, we can say that the combined use of external debt and free trade was the driving force behind the development of underdevelopment in Latin America. This is of course related to the social structure of Latin American countries. The local ruling classes, including the comprador bourgeoisie, made these choices in their own interest.

At the end of the 18th century, several Latin American regions, although still under colonial rule, accomplished a real artisanal and manufacturing development, mainly supplying local markets. Great Britain’s support for the Latin American people’s desire for independence stemmed from a desire for economic domination over the region. From the beginning Great Britain’s condition for recognizing independent states were clear: They had to allow free entry of English goods into their territory (the aim was to limit import duties to about 5%). Most new states agreed and the local producers, particularly artisans and small entrepreneurs, were put into great difficulty. [36] British goods invaded the local markets.

The British authorities practised highly protectionist policies until 1846. [37] This propelled the rise of Britain as the foremost industrial, financial, commercial, and military power during the 19th century. Whereas from 1810–1820 they had entered into agreements with the independentist Latin American leaders to open the economies of the still-developing new states to British goods and investments, [38] the British authorities were protective of their own industries and trade. Britain remained at the forefront by strongly protecting its market and its booming industries while destroying the industries (for example India’s textile industry) of its competitors. Only once British industry had achieved a prominent technological lead did Britain embrace free trade since it need no longer worry about any serious competition. Paul Bairoch writes that starting from the late 1840s, “the most highly developed country had become the most liberal, which made it easy to equate economic success with a free trade system, whereas in fact, this causal link had been just the opposite.” [39] Bairoch adds that “before 1860 only a few small Continental countries, representing only 4% of Europe’s population, had adopted a truly liberal trade policy.” [40] These were the Netherlands, Denmark, Portugal, Switzerland, Sweden, and Belgium. Let us not forget that the United States remained protectionist throughout the 19th century (and during most of the 20th century).

George Canning, a prominent British politician, [41] wrote in 1824: “The deed is done, the nail is driven, Spanish America is free; and if we do not mismanage our affairs sadly, she is English.” Thirteen years later, Woodbine Parish, the British consul in La Plata, described a gaucho from the Argentine pampas in the following way:

Take his whole equipment–examine everything about him–and what is there not of rawhide that is not British? If his wife has a gown, ten to one it is made in Manchester. [42]

Great Britain did not need to depend on military conquests to achieve this (although it did not hesitate to use force whenever it felt it necessary). It used two very effective economic weapons–granting international credits and imposing the abandonment of protectionism.

Latin America’s external debt crises: 19th-21st century

Since they gained independence in the 1820s Latin American countries have experienced four debt crises.

The first occurred in 1826 (ensuing from the first major international capitalist crisis originating in London in December 1825) and continued until 1840-1850.

The second broke out in 1876 and ended in the early 20th century. [43]

The third began in 1931 following the 1929 U.S. crisis and lasted until the late 1940s.

The fourth crisis burst in 1982 when the U.S. Federal Reserve took critical decisions on interest rates and plunging commodity prices. This crisis ended in 2003-2004 when foreign exchange revenues saw significant growth, thanks to increased commodity prices. Latin America also benefited from international interest rates, which were drastically lowered by the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of England after the Northern banking crisis erupted in 2008-2009.

A fifth crisis has been brewing since.

When and how these crises break out is closely linked to the global economy and to the most industrialized economies in particular. Each debt crisis was preceded by a boom in the central economies when a part of the surplus capital was recycled into the peripheral economies.

Each phase spawning the crisis (during which the debt increased sharply) corresponded to the end of a long expansionary period in the most industrialized countries. That has not happened in the current crisis because this time only China has been through a long expansionary period. Usually, the crisis in indebted peripheral countries is caused by external factors, e.g. a recession or a financial crash striking the major industrialised economies, or a policy change in interest rates implemented by the central banks of the major powers of the time, etc.

The observations above contradict the dominant narrative propagated by the economic-historical schools of thought [44] and transmitted by the mainstream media and governments. It claims that the crisis that erupted in London in December 1825 and spread to other capitalist powers, resulted from the over-indebtedness of Latin American States; the crisis of 1870 resulted from the indebtedness of Latin America, Egypt and the Ottoman Empire; that of 1890 which nearly caused the bankruptcy of one of the principal British banks, from Argentina’s over-indebtedness; that of the 2010s, from the over-indebtedness of Greece and more generally the “PIGS” (Portugal, Ireland, Greece, Spain).

Capitalism has continued its offensive against collective commons

Capitalism has continued its offensive against collective commons for two reasons: 1. The commons have not yet entirely disappeared and therefore they limit the total domination of capital, which consequently seeks to appropriate them or reduce them to the bare minimum. 2. Important struggles have recreated commons during the 19th and 20th centuries. These commons are constantly being challenged.

During the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, popular movements recreated social commons by developing systems of collective support

During the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, popular movements recreated social commons by developing systems of collective support: cooperatives, strike funds, solidarity funds. The victories of the Russian revolution also led to a short period of creation of common properties, until Stalinism degenerated into dictatorship and shamefully privileged a bureaucratic caste as described by Leon Trotsky in 1936 (Leon Trotsky The Revolution Betrayed. [45]).

In many capitalist countries (in varying degrees of development) the governments realized that to maintain social peace and even to avoid a resurgence of revolutionary movements some scraps had to be thrown to the populations. This resulted in the development of welfare states.

After WW2, from the second half of the 1940s to the end of the 1970s the wave of decolonizations mainly in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and the victorious revolutions in China (1949) and Cuba (1959) led to the redeployment of some collective commons notably through the nationalizations of strategic infrastructures (Suez canal in 1956 by the Nasser regime) and commodities such as copper by Salvador Allende in Chile in the early 1970s and petroleum resources (Algeria, Libya, Iraq, Iran…).

This period of reaffirming collective commons is expressed in several United Nations documents from the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights to the 1986 Declaration on the Right of Development which in article 1 paragraph 2 affirms: “The human right to development also implies the full realization of the right of peoples to self-determination, which includes,(…) the exercise of their inalienable right to full sovereignty over all their natural wealth and resources.” [46] This inalienable right of peoples to full sovereignty over their resources is constantly challenged by the IMF, the World Bank and the majority of governments in the interests of big private corporations.

Social reproduction has also come to the forefront

The activity of social reproduction has also come to the forefront of concerns about the commons through the work of feminist movements. As Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya and Nancy Fraser write in their manifesto Feminism for the 99%, [47] “Finally, capitalist society harbours a social-reproductive contradiction: a tendency to commandeer for capital’s benefit as much ’free’reproductive labor as possible, without any concern for its replenishment. As a result, it periodically gives rise to ’crises of care,’ which exhaust women, ravages families, and stretch social energies to the breaking point” (page 65). The authors’ define social reproduction as follows “It encompasses activities that sustain human beings as embodied social beings who must not only eat and sleep but also raise their children, care for their families, and maintain their communities, all while pursuing their hopes for the future. These people-making activities occur in one form or another in every society. In capitalist societies, however, they must also serve another master, namely, capital, which requires that social-reproductive work produce and replenish ‘labour’ power” (page 68).

The activity of social reproduction has also come to the forefront of concerns about the commons through the work of feminist movements. As Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya and Nancy Fraser write in their manifesto Feminism for the 99%, [47] “Finally, capitalist society harbours a social-reproductive contradiction: a tendency to commandeer for capital’s benefit as much ’free’reproductive labor as possible, without any concern for its replenishment. As a result, it periodically gives rise to ’crises of care,’ which exhaust women, ravages families, and stretch social energies to the breaking point” (page 65). The authors’ define social reproduction as follows “It encompasses activities that sustain human beings as embodied social beings who must not only eat and sleep but also raise their children, care for their families, and maintain their communities, all while pursuing their hopes for the future. These people-making activities occur in one form or another in every society. In capitalist societies, however, they must also serve another master, namely, capital, which requires that social-reproductive work produce and replenish ‘labour’ power” (page 68).

What the authors add later on brings us closer to the situation highlighted by the current multidimensional crisis of capitalism and the coronavirus pandemic:

[Capitalism assumes] that there will always be sufficient energies to produce the labourers and sustain the social connections on which economic production, and society more generally, depend. In fact, social-reproductive capacities are not infinite, and they can be stretched to the breaking point. When a society simultaneously withdraws public support for social reproduction and conscripts its chief providers into long and gruelling hours of low-paid work, it depletes the very social capacities on which it relies. (page 73)

What is denounced in this passage allows us to better understand the fragility of capitalist society in the face of epidemics, the inability of governments to do what is necessary in time to best defend the population, the pressure put on workers in the essential and vital sectors to come to the aid of the population while, at the same time, as a result of the decisions of these same governments, they are underpaid, devalued and in insufficient numbers. The same can be said about the causes of the failure of governments to address the consequences of climate change and the under-equipment and lack of civil protection personnel in the face of increasingly frequent ’natural disasters’.

Public debt has been and still is systematically used as a means of grabbing commons

Since the 1970s public debt has systematically been used as a means of grabbing commons, as much in the North as in the South. The CADTM, along with other social movements, has not ceased to denounce this since the 1980s. We have devoted a dozen books [48] and several hundred articles to this issue. It is very satisfying to see that more and more writers are now highlighting the issue of debt as a weapon against public property. [49]

We cite once again Feminism for the 99%:

Far from empowering states to stabilize social reproduction through public provision, it authorizes finance capital to discipline states and publics in the immediate interests of private investors. Its weapon of choice is debt. Finance capital lives off of sovereign debt, which it uses to outlaw even the mildest forms of social-democratic provision, coercing states to liberalize their economies, open their markets, and impose ’austerity’ on defenceless populations. (page 77)

All through the neoliberal offensive that has been the dominating ideological tendency since the 1980s, governments and different international institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF have insisted on the “duty” to repay external debt in order to generalize a tidal wave of privatizations of many countries’ strategic economic sectors, public services and natural resources, whether in developed countries or not. As a consequence, the previously existing tendency towards reinforcing collectivism has been reversed.

The list of assaults on public properties based on public debt is long. Some have accelerated the ecological crisis and the development of zoonoses: rapid deforestation, intensive animal farming and monocrops to gain foreign currencies in order to pay foreign debt, all of this in the framework of structural adjustment policies induced by the, already ill mentioned World Bank and IMF.

Some of the political policies imposed through debt repayment obligations have seriously hindered the capacity of states and populations to deal with public health crises including the coronavirus pandemic: stagnation or reduction of public health budgets, imposing compliance to medical patents, renouncing the use of generic drugs, giving up producing medical equipment domestically, preferring private sector medical treatment and medicine distribution, suppressing free access to medical care in many countries, reducing the quality of working conditions in the medical sector and introducing the private sector into numerous essential public health services.

Already, over a century and a half ago Marx put it in a nutshell: “Public debt: the alienation of the state–whether despotic, constitutional or republican–marked with its stamp the capitalistic era”. [50] Once we have become aware of the way repayment of public debt is instrumentalised to impose mortal neoliberal capitalist policies, we know we must fight for the cancellation of illegitimate debt. Marx also wrote that “Public credit and private credit are the economic thermometer by which the intensity of a revolution can be measured.” [51]

The coronavirus pandemic has widened the gap between the Global North and the Global South

Confronted with the coronavirus pandemic that started end of 2019-beginning of 2020, the governments of long-standing imperialist powers (Western Europe, North America, Japan, Australia-New Zealand) and private pharmaceutical corporations have widened the gap between the Global North and the Global South.

The pharmaceutical corporations find it far safer and more profitable to give priority to supplying the rich countries that not only can pay high prices for the vaccines but are willing to make advance payments covering the production costs to come. This is clearly illustrated in the analysis of the distribution figures of the vaccines. Moderna has allocated 84% of its production to the U.S. and the EU; Pfizer/BioNTech has allocated 98% and for Johnson & Johnson the equivalent figure is 79%. Pfizer/BioNTech has delivered to Sweden alone nine times more doses than it has delivered to all the low-income countries put together. [52]

Mapping the vaccine doses clearly shows that part of the world is being left out. In October 2021, of the 5.76 billion doses injected, only 0.3% have gone to the lowest income countries that have a total population of 700 million people (see: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations). Only 2.7% of the populations of the 27 lowest income countries have received a vaccine jab against over 60% in North America and Western Europe.

The leaders of a handful of rich countries are opposed to lifting patents as requested by the Global South, particularly the European Union, Switzerland and Japan. As for the USA, President Joe Biden has said he is favourable to lifting the patents but has not taken any action towards requiring governments who are blocking the question in the WTO to do so.

Thanks to the possession of patents and to governmental complicity, Big Pharma is garnering undue revenues

The prices asked by Big Pharma for Covid vaccines are exorbitant. Two examples: according to Public Citizen estimates, a Pfizer/BioNTech Covid vaccine dose costs about $1.20 to mass produce; a Moderna vaccine dose costs $2.85 to mass-produce. [53] In some countries the Pfizer/BioNTech dose is sold at $23.50 and the Moderna dose is priced as high as $37.

The usual excuse for such prices is the costs of R&D and clinical trials. These arguments are not valid in the case of Covid vaccines as these costs have been financed by public authorities.

The decision by Northern governments to proceed to a third injection delights Big Pharma which sees more fabulous profits in gestation. If the patents on vaccines, tests and drugs are not lifted or actually abolished, the big private companies that dominate the pharmaceutical sector will reap colossal revenues for the next 20 years at the expense of the global population, state budgets and public health systems. The stakes are enormous because booster injections will be recommended and/or imposed. Imagine an annual injection for 20 years with a vaccine protected by a patent and therefore sold at a high price… Big Pharma shareholders may gleefully anticipate huge incomes.

In a well-documented report entitled The Inside Story of the Pfizer vaccine: ‘a once-in-an-epoch windfall, the Financial Times explains that thanks to its agreement with the German company BioNTech this U.S. company took the lead over its competitors Moderna, Astra Zeneca, Johnson & Johnson in the production and selling of the vaccine. Like Moderna, it gave priority to the rich countries. By the end of 2021, it has covered 80% of the Covid vaccine sales in the EU and 74% in the U.S.. It was very demanding towards the governments of countries in the Global South as it made changing their national laws a condition to supplying vaccines.

Before deals could be agreed, Pfizer demanded that countries change national laws to protect vaccine makers from lawsuits (…). From Lebanon to the Philippines, national governments changed laws to guarantee their supply of vaccines. [54]

The paper quotes Jarbas Barbosa, the assistant director of the Pan American Health Organization, who said that Pfizer’s conditions were “abusive, during a time when due to the emergency [governments] have no space to say no.”

The Financial Times further explains that “negotiations with South Africa were particularly tense. The government complained that Pfizer made what its former health minister Zweli Mkhize called ‘unreasonable demands,’ which it said delayed the delivery of vaccines.” The paper further reports that “at one stage, [Pfizer] had asked the government to put up sovereign assets to cover the costs of any potential compensation, something it refused to do. The Treasury rejected the health department’s request to sign the deal with Pfizer, according to people familiar with the matter, arguing it was equivalent to ‘surrendering national sovereignty.’ But Pfizer did insist on indemnity against civil claims and required the government to provide finance for an indemnity fund. The South Africans said to me: ‘These guys are putting a gun to our head,’ says a senior official familiar with African vaccine procurement efforts. ‘People were screaming for a vaccine and they signed whatever was put in front of them.”

South Africa’s Health Justice Initiative is about to file a lawsuit to enforce the publication of the contracts signed between Pfizer and the South African government.

“We want to know what else they played hardball on,” says Fatima Hassan, founder of South Africa’s Health Justice Initiative.

A private company can’t have so much power. The contract should be open. They would tell the story of what Pfizer has managed to extract out of sovereign countries around the world.

The outrageous attitude of governments in the most industrialized capitalist countries who deliberately deepen the gap with people in low-income countries finds a telling illustration in the third jab. Up to November 2021, those governments had had a third vaccine jab administered to 120 million inhabitants in rich countries while the total figure of vaccines administered in low-income countries only amounts to 60 million. [55] This is public health apartheid.

Moreover, Amnesty International is right to denounce AstraZeneca, BioNTech, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, Novavax and Pfizer for those “six companies at the helm of the global COVID-19 vaccine roll-out are fuelling an unprecedented human rights crisis because of their refusal to waive intellectual property rights and share vaccine technology, with most of the companies failing to prioritise vaccine deliveries to poorer countries.” [56]

COVAX is not a solution

Governments in countries of the South who wish to give their population the possibility of getting vaccinated will have to contract debts since COVAX-type initiatives are blatantly wanting and actually reinforce the hold of the private sector. COVAX is run jointly by three bodies: 1. The GAVI Alliance, which is a private structure that brings together companies and States, 2. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which is another private structure that also includes capitalist companies and States, and 3. The WHO, which is a UN specialized agency.

Among the companies that finance and influence GAVI we find the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, Blackberry, Coca Cola, Google, the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Wholesalers, the Spanish bank Caixa, the Swiss bank UBS (the biggest asset management bank in the world), financial companies such as Mastercard and Visa, the aerospace manufacturer Pratt & Whitney, the American multinational consumer goods corporation Procter & Gamble, the British multinational consumer goods company Unilever, the oil company Shell International, the Swedish musical streaming company Spotify, the Chinese company TikTok and the car manufacturer Toyota. [57]

The entity which co-directs COVAX is the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which was founded in 2017 at Davos on the occasion of a meeting of the World Economic Forum. Among the private companies who finance and strongly influence the CEPI we find, once again, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which has invested $ 460 million.

The membership of the COVAX initiative reveals much about the unwillingness of the various WHO member States to take responsibility for the struggle against the pandemic, in particular as regards public health. Such an attitude is typical of the damage done by the neoliberal groundswell that has swept the planet since the 1980s. The Secretariat General of the United Nations and the leadership of the specialized agencies within the UN system (for example the WHO in the area of health and the FAO for agriculture and food) have been moving in the wrong direction for the past thirty to forty years by relying more and more on private initiatives directed by a limited number of big global companies. Heads of State and of government have moved in the same direction. In fact, it can even be said that they made the first move. In so acting, they have allowed major private companies to be associated in decisions and derive advantages from the choices that are made. [58]

Remember that over 20 years ago researchers and social movements specialized in care proposed that the public authorities should invest sufficient amounts to create effective remedies and vaccines against the “new generation” viruses stemming from the increase in zoonoses. The overwhelming majority of states have chosen to rely on the private sector and have given them access to the results of research conducted by public entities when they should have invested directly in the production of vaccines and treatments within the framework of a public health service.

As we have seen, the COVAX initiative is not the solution that is needed.

COVAX had promised to supply, by the end of 2021, 2 billion doses to the countries of the South who request them and who are associated with the initiative. In reality, figures show that at the beginning of September 2021 only 243 million doses had been shipped. [59] As a result, the goal of 2 billion doses has been pushed back to the first semester of 2022.

All the major powers of the North have fallen short of the promises they made.

For example, on 21 October, the European Union along with Iceland and Norway had only delivered 52 million doses (10%) out of the 500 million they had promised. [60]

According to an official assessment in December 2021, COVAX has so far only delivered about 600 million doses in 144 countries or territories, a long cry from the initial objective of two billion in 2021. To date, 9 doses have been administered for 100 inhabitants in low-income countries (as defined by the World Bank). In comparison, the world average is 104 per 100 people. This figure rises to 149 for high-income countries. Africa is the continent with the lowest rate of vaccination (18 doses for 100 inhabitants). [61]

C-TAP (COVID-19 Technology Access Pool) is another disappointing WHO initiative. C-TAP includes the same protagonists as COVAX. It was created to pool intellectual property, data and fabrication processes by encouraging pharmaceutical companies who hold patents to cede to other companies the right to produce the vaccine, medicines or treatments by facilitating technology transfer.

Yet so far not a single vaccine producer has shared patents or know-how via C-TAP. [62]

Faced with the failure of COVAX and C-TAP, the signatories of the Manifesto ’End the system of private patents! launched by the CADTM in May 2021 are right in saying that:

Initiatives such as COVAX or C-TAP have failed miserably, not only because of their inadequacy but above all because they reflect the failure of the current system of global governance in which rich countries and multinationals, often in the form of foundations, seek to reshape the world order to their liking. Philanthropy and burgeoning public-private initiatives are not the answer. They are even less so in the face of today’s global challenges in a world dominated by States and industries driven solely by market forces and seeking maximum profits. [63]

Returning to a historical overview

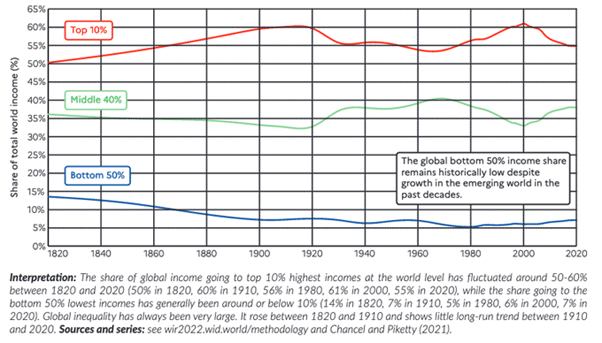

According to the Global Inequality Report 2022, published in early December 2021 and coordinated by Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, the share of income currently captured by the poorest half of the world’s population is about half of what it was in 1820, before the great divergence between the Western countries and their colonies The share of personal income of the poorest 50% of adults in the world, about 3 billion people, is half of what it was in 1820!

Beyond the North-South divide: class exploitation in all countries

This overview of the global situation is fundamental. It must be complemented by the huge inequalities in income and wealth accumulation within nations. Capitalism has spread on a global scale. In this system, the capitalist class, which accounts for a tiny minority of the population, gets richer and richer thanks to the wealth produced by the labour of the majority of the population, but also thanks to the exploitation of nature, without any concern for its physical limits. Without any leverage on the means of production, most men and women are forced to sell their labour force to capitalists (who own the means of production), who try to pay the workforce as little as possible, thus preventing a majority of the population from escaping the social conditions in which they find themselves. Conversely, wealth accumulated by capitalists makes it possible for them to invest in various sectors so as to diversify their sources of profit as they exploit both humans and nature.

In order to keep profits at their highest level and to make sure that this mode of production endures, the capitalist class tries not only to pay as low wages as possible but also to prevent redistribution of wealth by paying as little tax as possible and by under-valuing social policies such as public services (whether housing, transport, health care or education). Capitalists also try to prevent workers from organizing, notably when they stand up against labour rights: the right to form trade unions, right to go on strike, right to collective bargaining, etc. Conversely, workers must organize if they want to acquire social rights and fight those inequalities. So there is a class struggle at an international level, the intensity of which depends on the level of collective organization of workers in a given place and at a given time, in the face of blatant injustices.

Economic inequalities between various groups can be measured through the wealthy people can claim and through people’s income (income from labour – wages, pensions, various social benefits – and income from capital such as corporate profits, dividends received by shareholders, etc.).

The poorest among the world population own literally less than nothing: they are indebted and owe money to their creditors–generally banks–namely to the richest portion of the population. In the United States, about 12% of the population, over 38 million inhabitants, are indebted beyond what they can ever hope to repay. [ 64] Their debts (mostly student loans and mortgages) are so high that the cumulated assets of the poorer 50% are negative (-0.1%). [65]

Conclusion

Since the beginning of the violent conquest of entire continents by European powers until today, we have witnessed a sequence of plundering, destruction of common goods, the genocide of populations, exploitation of labour and nature… Gradually the capitalist system has become widespread on a global scale. This system subjects human beings and the whole of nature to intensive exploitation in order to accumulate maximum short-term profits and to guarantee the enrichment of the capitalist class, which represents no more than 1% of the world’s population. According to the World Wealth Report produced annually by the Credit Suisse bank, only 1% of the world’s adults own 45% of all personal wealth while nearly 3 billion people own nothing [66].

The capitalist system has produced a multi-dimensional global crisis that brings forth life on Earth to the brink of extinction.

It is high time to act for a complete break with the capitalist mode of production and property. We need to get out of the Capitalocene.

Bibliography

- AMIN, S. (1974), Accumulation on a World Scale: A. Critique of the Theory of Underdevelopment. (Monthly Review Press, 1974).

- BAIROCH, P. (1995), Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes, University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- BAYLY, C.A., (2004), The Birth of the Modern World, 1780-1914: Global Connections and Comparisons, Oxford, Blackwell, 2004.

- BEAUD, M. (1981), A History of Capitalism, 1500-2000, Monthly Review Press; Revised and Updated ed. edition (June 1 2001).

- BRAUDEL, F. (1985), Civilisation and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century, 3 vol., Fontana, London.

- CHAUDHURI, K.N. (1978), The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company, 1660–1760, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- CHAUDHURY, S. (1999), From Prosperity to Decline: Eighteenth Century Bengal, Manohar, New Delhi.

- CHAUDHURY, S. ET MORINEAU M. (1999), Merchants, Companies and Trade: Europe and Asia in the Early Modern Era, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- CLAIRMONT, F.F. (1996), The Rise and Fall of Economic Liberalism, Southbound and Third World Network, 356 p.

- COLOMBUS, C., The Voyage of Christopher Columbus: Columbus’ Own Journal of Discovery Newly Restored and Translated (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

- DAVIS M. (2001), Late Victorian Holocausts, El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, Verso, London.

- GUNDER FRANK, A. (1978), World Accumulation 1492-1789, New York: MacMillan, 1978.

- LUXEMBURG, R. (1913), The accumulation of capital. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1963.

- MADDISON, A., (2007), Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD: Essays in Macroeconomic History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- MANDEL, E., Late Capitalism, NLB, London, 1975, 599 pp. (& later ed., publ. by Verso, London)

- MARX, K. (1867), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy; Volume I, Lawrence & Wishart, London.

- NEEDHAM, J. et al. (1954–2000), Science and Civilisation in China, 50 large sections, several co-authors, several volumes, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- POLO, M., Marco Polo’s Le Devisement du Monde, Boydell & Brewer, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England, 2013.

- POMERANZ, K. (2000), The Great Divergence, Princeton University Press, Princeton.•

- SAHAGUN, F. B. de, Histoire générale des choses de la Nouvelle-Espagne, François Maspero, Paris, 1981, 299p.

- SHIVA, V. (1991), The Violence of the green revolution, Third World Network, Malaysia, 1993, 264 p.

- SMITH, A. (1776), An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, republished by University of Chicago Press, 1976

- SUBRAHMANYAM, S. (1997), The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- WALLERSTEIN, I. (1983), Historical Capitalism with Capitalist Civilization, Verso, London, 1983.

Notes:

[1] This article has several origins. This version was presented on 28 October 2021 at an online conference organised by the University of the Philippines (UP) Cebu, as part of a seminar entitled Decolonial Perspectives: Reclaiming our rights as People from the Global South. It is a greatly expanded version of the author’s lecture given in Kerala, India, on 24 January 2008 under the title Impacts of Globalisation on Poor Peasants. The parts that have been added were written in 2017 and 2021.

[2] To this must be added the Danes, who made a few conquests in the Caribbean Sea, not forgetting Greenland in the North (which had been ’discovered’ several centuries earlier). For the record, the Norwegians had reached Greenland and “Canada” well before the 15th century. See in particular Leif Ericsson’s voyage in the early 11th century to the ’Americas’ (where he moved from Labrador to the northern tip of Newfoundland), where a brief, long-forgotten settlement was established at l’Anse aux Meadows.

[3] The name America comes from that of Amerigo Vespucci, an Italian sailor at the service of the Spanish crown. Indigenous peoples from the Andes (Quechuas, Aymaras, etc..) call their continent Abya-Yala

[4] Among natural resources, one must include the new biological resources brought back by the Europeans to their countries, then diffused in the remaining of their conquests and further: maize, potatoes, sweet potatoes, cassava, capsicum, tomatoes, pineapple, cocoa and tobacco.

[5] Figures concerning the population of the Americas before the European conquest have been differently estimated. Borah estimates that the population of the Americas reached 100 million in 1500, while Biraben and Clark, in separate studies, provide estimates of nearly 40 million. Braudel evaluates the population of Americas between 60 and 80 million in 1500. Maddison adopts a much lower estimate, assuming that the population of Latin America reached 17.5 million in 1500 and reduced by more than half, a century after the conquest. In the case of Mexico, he estimates that the population went from 4.5 million in 1500 down to 1.5 million one century later (i.e. a depopulation of two-thirds of inhabitants). In this article, we adopt the conservative hypothesis as a precaution. Even within this hypothesis, the invasion and conquest of the Americas by Europeans can clearly be counted as a crime against humanity and genocide. The European powers that conquered the Americas exterminated entire peoples and the dead can be counted by the millions, most probably by tens of millions.

[6] The Spanish and Portuguese crowns who ruled South America, Central America and a fraction of the Caribbean during three centuries used, as Catholic powers, the support of the Pope to perpetrate their crimes. One must add that, at the end of the 15th century, the Spanish crowns expelled Muslims and Jews (who did not convert to Christianity) during and following the Reconquista (that ended on January 2 1492). Jews who did not renounce Judaism, emigrated and mainly took refuge in Muslim countries within the Ottoman Empire, which showed greater tolerance towards other religions.

[7] From that point of view, the message of Pope Benedict XVI during his trip to Latin America in 2007 is very offensive against the memory of the peoples who were victims from the European domination. Indeed, far from acknowledging the crimes committed by the Catholic Church against indigenous populations of the Americas, Benedict XVI claimed that they were waiting for the message of Christ, brought by the Europeans since the 15th century. Benedict XVI should answer for his words in front of the courts of justice.

[8] From Asia, Europeans brought back the production of silk textiles, cotton, the blown glass technique, cultivation of rice and sugar cane.

[9] Namely the famous Silk Road between Europe and China followed by the Venetian Marco Polo at the end of the 13th century.

[10] Officially, Christopher Columbus tried to rejoin Asia taking the Western route but we know he hoped to find new lands unknown of Europeans.

[11] Starting with the 16th century, the use of the Atlantic Ocean for travelling from Europe to Asia and the Americas marginalized the Mediterranean Sea during four centuries until the boring of the Suez Canal. While the main European harbours were in the Mediterranean until the end of the 15 century (Venice and Genoa in particular), the European harbours open to the Atlantic gradually took over (Antwerp, London, Amsterdam).

[12] See Eric Toussaint, Your Money or Your Life. The Tiranny of Global Finance. Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2005, chapter 7. The first international debt crisis occurred at the end of the first quarter of the 19th century, simultaneously hitting Europe and the Americas (it is related to the first global crisis of overproduction of commodities). The second global debt crisis exploded at the end of the last quarter of the 19th century and its repercussions affected all continents.

[13] In coastal towns of East Africa, traders (Arabs, Indians of Gujarat and Malabar –Kerala- and Persians) were heavily involved in business, importing silk and cotton fabrics, spices and porcelain from China and exporting cotton, wood and gold. One could meet professional sailors, who were experts in the monsoon conditions of the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean.

[14] Needham, 1971, p. 484

[15] In the 15th Century, Peking was connected to the areas which produced its food supplies by the Grand Canal which was 2300 km long and was easily navigated by barges thanks to an ingenious lock system.

[16] There have been many debates about European gross domestic product (GDP) per head compared to the rest of the world. Estimates vary enormously according to the source used. Different authors, such as Paul Bairoch, Fernand Braudel and Kenneth Pomeranz, reckon that, in 1500, European GDP per capita was no higher than that of China and India. Maddison, who strongly opposes this view (for underestimating the level of development in Western Europe), reckons that India’s per capita GDP in 1500 was $550 (1990 equivalent) and that of Western Europe $750. Whatever the disagreements between these authors, it is clear that in 1500, before the European powers set out to conquer the rest of the world, they had a per capita GDP that was at most (i.e. according to Maddison’s deductions) between 1.5 and 2 times that of India, whereas 500 years later, the difference was tenfold. It is quite reasonable to conclude that the use of violence and extortion by the European powers (later joined by the United States, Canada, Australia and other countries with significant European immigration) was largely the basis of their current economic superiority. The same reasoning can be applied to Japan, but in a different timeframe because Japan, with a GDP per capita lower than China’s between 1500 and 1800, only became an aggressive, conquering capitalist power at the end of the 19th Century. >From that time on, the growth of GDP was staggering: it increased thirty-fold between 1870 and 2000 (if we are to believe Maddison). This is the period which really made the difference between Japan and China.

[17] See Maddison, 2001 p.110

[18] See Gunder Frank, 1977 p. 237-238

[19] The Dutch did the same with Chinese porcelain production techniques, which they copied and since then present as ceramics, faience and blue and white Delft pottery.

[20] Karl Marx. 1867. Capital, vol I, www.marxists.org

[21] Rosa Luxemburg. 1913. www.marxists.org

[22] Polanyi, K. 1944. The Great Transformation, Beacon Press, Boston

[23] Silvia Federici (2004), Caliban and the Witch, Autonomedia, New York, 2004.

[24] The Young Karl Marx, French-German-Belgian biographical film by Raoul Peck, released in 2017.

[25] Daniel Bensaïd, The Dispossessed,

Karl Marx’s Debates on Wood Theft and the Right of the Poor, University of Minnesota Press, 2021, 160 pages

[27] See: Sophie Perchellet, Haïti. Entre colonisation, dette et domination, CADTM-PAPDA, 2010 cadtm.org. Ordinance of the French Emperor, 1825, Article 2. “The current inhabitants of the French part of Saint Domingue will pay an amount of 150 million francs to the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations (Deposits and Consignments Fund) of France in five equal annual instalments, the first of which will be due on December 1, 1825. This is intended to compensate the former colonial rulers who demand to be compensated.” This amount was reduced to 90 million francs a few years later”.

[31] Periphery countries, compared to the major European capitalist powers (Great Britain, France, Germany, Netherlands, Italy, Belgium) and the U.S..

[32] Jacques Adda is one of the authors to have drawn attention to this issue. See: Jacques Adda. 1996. La Mondialisation de l’économie, tome 1, p.57-58 (in French)

[33] To learn more about the factors besides the rejection of external debt, read Perry Anderson Lineages of the Absolutist State (first published by NLB, 1974. Verso Edition 1979), on Japan’s transition from feudalism to capitalism.

[34] Kenneth Pomeranz, who has been keen on highlighting the factors thwarting China’s race to become one of the major capitalist powers, does not give importance to external debt. In fact, his study focuses on the pre-1830 to 1840 era. However, his analysis is very rich and inspiring. See: Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence, Princeton University Press, 2000, 382 pages.

[35] Rosa Luxemburg. 1969. L’accumulation du capital, Maspero, Paris, Vol. II, p. 60 (in French) (In English: The Accumulation of Capital, Section 3, Chapter 28) www.marxists.org

[36] In his invaluable book Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, (trans. Cedric Belfrage, New York: Monthly Review Press, 1973), Eduardo Galeano has portrayed this destruction with realism and compelling imagery. To date, this book remains the best and most accessible presentation of the various forms of domination and dispossession suffered by the Latin American peoples. The work is well documented and points out the responsibility of the dominant classes, both on the Old Continent and in the New World.

[37] See Paul Bairoch, Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

[38] See Luis Britto García, El pensamiento del Libertador: Economía y Sociedad. (Caracas: BCV, 2010).

[39] Paul Bairoch, Economics and World History, 21

[40] Paul Bairoch, Economics and World History, 22

[41] George Canning, Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, became Prime Minister in 1827.

[42] Woodbine Parish, Buenos Ayres and the Provinces of the Rio de la Plata (London: John Murray, 1839), 338. Quoted by Eduardo Galeano in Open Veins of Latin America, 176.

[43] Venezuela’s refusal to repay its debt ultimately resulted in a major face-off with the imperialist powers of North America, Germany, Britain and France. In 1902, the latter sent a united military fleet to block the port of Caracas and to persuade Venezuela, through gunboat diplomacy, to resume debt repayment. Venezuela could not wrap up its payments before 1943.

[44] See the 19th-century writings of Sismondi and Tugan Baranovsky in particular, as well as the headlines of the print media and the speeches by the European governments of that period.

[45] Leon Trotsky, 1936, The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and Where is It Going?, New York: Doubleday, Doran and Co., 1937.

[46] UN, 41/128. Declaration on the Right to Development, Adopted by the General Assembly 4 December 1986, un-documents.net

[47] Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya and Nancy Fraser, Feminism for the 99% a manifesto, available here:outraspalavras.net

[48] See Eric Toussaint, Your Money or Your Life. The Tyranny of the Global Finance, Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2005; Debt, the IMF, and the World Bank, Sixty Questions, Sixty Answers, Monthly Review Press, New York, 2010; The World Bank–A Critical Primer, Between the lines, Toronto/Pluto Press, London/David Philips Publisher, Cape Town/CADTM, Liège, 2008.

Among the precursory works on debt as an instrument for the imposition of neoliberal policies, books by two women should be highlighted: Susan George on the one hand and Cheryl Payer on the other. George, Susan, 1988. A Fate Worse than Debt Penguin, and 1992, The Debt Boomerang: How Third World Debt Harms Us All Pluto Press. Cheryl Payer, 1974, The Debt Trap: The International Monetary Fund and the Third World, Monthly Review Press, New York and London, and 1991, Lent and Lost. Foreign Credit and Third World Development, Zed Books, London, 154 pp.

[49] See for instance Verónica Gago and Luci Cavallero, “Debt is a war against women’s autonomy”, published on 20 May 2021.

[50] Karl Marx. 1867. Capital, vol I, Part VIII: Primitive Accumulation, Chapter XXXI: Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist

[51] Karl Marx, The Class Struggles in France, 1848 to 1850, Selected Works, Volume 1, Progress Publishers, Moscow 1969

[52] Amnesty International report « A DOUBLE DOSE OF INEQUALITY, PHARMA COMPANIES AND THE COVID-19 VACCINES CRISIS », published 22 September 2021, www.amnesty.be

www.amnesty.org.uk.

[53] Public Citizen, “How to Make Enough Vaccine for the World in One Year”, published 26 May 2021, www.citizen.org.

[54] Financial Times, The inside story of the Pfizer vaccine: ‘a once-in-an-epoch windfall’, 1 December 2021. www.ft.com.

[55] Figures provided by the Financial Times in the article mentioned.

[56] Amnesty International, “COVID-19: Big Pharma fuelling unprecedented human rights crisis”, published 22 September 2021, www.amnesty.org.uk.

[57] GAVI, Donor profiles, www.gavi.org

[58] The major agribusiness corporations had invited themselves to the UN Food Systems Summit 2021 whereas, in fact, they are one of the causes of, and not a solution to, the worldwide food and environmental crises. A number of movements have pointed this out. See The Guardian, “Corporate colonization’: small producers boycott UN food summit,” www.theguardian.com. See also the news report by Democracynow.org from New York: www.democracynow.org. See also (in French) CCFD-Terre Solidaire, “Food system summit : alerte sur un sommet coopté par le secteur (…)” ccfd-terresolidaire.org

[59] See page 5 of the Amnesty International report www.amnesty.be cited above.

Also www.politico.eu

[61] See ourworldindata.org and qz.com, also, in French, www.france24.com

[62] See page 5 of the Amnesty International report www.amnesty.be cited above

[63] From the Manifesto “End the System of Private Patents!” www.cadtm.org

[64] Chuck Collins, “Negative Wealth Matters”, Inequality.org, 28 January 2016.inequality.org (accessed 21 January 2020).