Summary: Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s attack on public health measures during COVID-19 is linked to undialectical perspectives rooted in Nietzsche, and contrasted to other thinkers like Toni Negri, Naomi Klein, and Peter Linebaugh. –IMH Editors

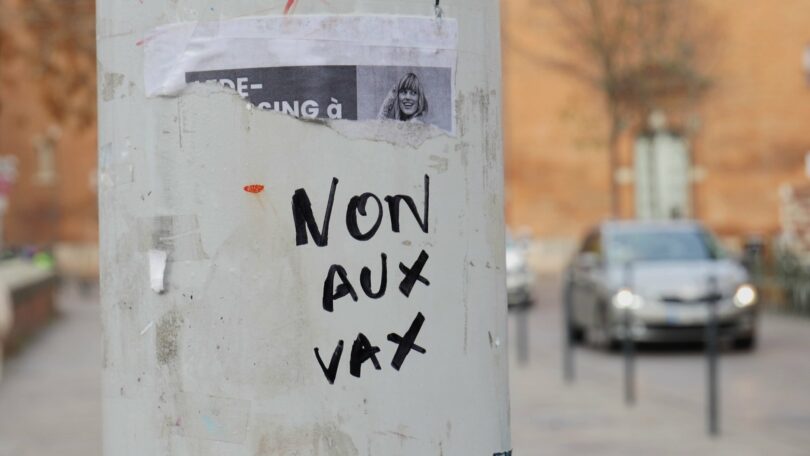

Padua, Italy — When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. The Italian political philosopher, Giorgio Agamben, who for decades has warned us about the seemingly unstoppable ability and will of even democratic states to impose a “state of exception”–a state of emergency powers overriding all law, constitutional restraints, and citizen or human rights–has now become the most sophisticated spokesperson for the anti-vax and other forces opposed to the public health restrictions due to the COVID-19 virus crisis. He has founded an intellectual group opposed to the restrictions, public health measures, vaccination requirements and other actions taken by public officials to combat the spread of the virus and its lethality.

Agamben is one of the most influential philosophers of recent years, and he was especially “hot” and in fashion during the Bush/War on Terror years after 9/11, when his analysis seemed to help explain the restrictions on constitutional and human rights. Agamben has many admirers, and his work has influenced that of many in and out of academia. His recent insistence, however, that the entire Covid pandemic is a manufactured crisis, whose true intent has been to impose a “biopolitical” regime that “reduces us all to mere biophysical existence”, making us into “lemmings” who, bending to the will of state power and direction have been stripped of all ethical, moral and cultural traits, leading us to stand naked in front of the sovereign, willing to accept the destruction of our liberties for the sake of presumed security, has led many to wonder whether his current stance throws light–or better shadow–on his previous work which has been so widely celebrated.

Since in 2011 I wrote and got published a lengthy attack on Agamben and his work,1 an essay I wrote when he was at the height of his popularity and his work at its most in fashion, I have to say that I saw something like this coming from a mile away, and think this seeming turn to the irrational Agamben was entirely predictable. But the problem with being a no-name independent scholar and activist publishing in a fine, reputable but hardly widely-read and followed journal an attack on the work of an intellectual superstar, is that you don’t have the impact you wish you had. So only now are people wondering what went wrong with Agamben. To which, the only reply is: nothing, his work was always wrongheaded. I hope to briefly explain why here.

Agamben is known mainly for his concept of the “state of exception” and for arguing, and seeming to demonstrate empirically, that the overriding of all constitutional or legal limits by state power has become the norm, not a “crisis” or a “state of emergency” but a sort of permanent state of emergency. So crushing of human and legal rights by reference to some crisis or emergency is the principal form of government–or better governance in the world today, including in the western democratic states. He uses categories from the Nazi philosopher Carl Schmitt to show how sovereignty is essentially the power to impose one’s will on others, that is, the power of the state or of its executive branch to declare a state of emergency at will and use that situation to put society into a Hobbesian state of nature–one where law does not yet exist, because law itself must be based on a prior condition in which law is made in the first place so that other laws can be fashioned based on this “constituent power”. Constituent power is a concept of Schmitt’s that the Italian autonomist Marxist Toni Negri has used with some creativity to describe the potential founding of new societies by social movements and revolutions, but which for Schmitt and Agamben instead describes the true power of the state that precedes law and constitutions, that power that makes law and constitutions in the first place, and so is mainly a menace, not a possibility, for popular forces. For Negri, this is the moment of revolution, when a movement is in a position to become the new order of society. For Agamben, it is instead the moment of state power that reveals the state’s real essence, as raw power to impose its will, the Leviathan of Hobbes. In the face of that state power, all of us, citizens and refugees alike, are mere Homo Sacer–an ancient Roman category that referred to persons who had no rights, nor any right to have rights, who could be killed with impunity. For Agamben, the Jews in the Nazi camps are the prototype of the human condition for all today.

I criticized Agamben ten years ago in my article of the time, and hold to my criticisms today, on the grounds of his not addressing any history or relationship of the state to capitalism and its processes, and of not addressing in any way the long history of struggles against capitalist expropriation and exploitation–the anti-slavery movement, the anti-colonial movements, the movements for women’s equality and the working class movements, as well as the democratization–partial as it is–of state power. By ignoring capitalism and the struggle against it, Agamben ignores the experiences of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, of colonized peoples, of women, of slaves and of proletarians, whose survival under capitalism is always contingent. Ignoring these central experiences of the modern world enables him to treat the states of emergency around the world and historically that are so important to him as more novel and more urgent and as new norms. Instead, as my list of social actors shows, the experience of being homo sacer in one form or another–of the very state he is warning us about, has in fact been the main experience of the majority of people around the world for centuries. And, until recently, with the end of slavery, advances in women’s rights, labor unions, democratization and advanced welfare state and social democracies, it has been the experience of the majority of people in every society since the rise of classes. I think these criticisms of his work still hold today, even before his recent seeming descent into madness over vaccinations, Covid restrictions and public health measures, positions I see as entirely in keeping with and consistent with his previous work, indeed their logical trajectory and outcome.

But it is the contrast of his work with that of Toni Negri’s on the shared concept of constituent power that I think can best show what problem is at the heart of not just both their work, but that of an entire field of works by various authors, of which Agamben is merely currently the worst and most extreme example.

Negri sees the state of exception as a potential moment of revolutionary reconstitution of society as a whole, to paraphrase the Communist Manifesto, Agamben as the moment of greatest peril, as the expression of a state power whose guarantees to citizens of their rights is worth no more than the paper it is written on, since those rights can be annulled at will at any moment and apparently are being so as the new norm across the world.

Each, we see, has a one-sided view of the whole thing, and of the relationships involved. What is missing, in other words, is any dialectic in either of their analyses, though to be fair Negri’s work does utilize dialectics in other ways in its analysis of the relationship of social movements, capitalism and state forms. But not in seeing the side of constituent power that Agamben sees and vice-versa. In each case, missing is an opposing side, or even an interlocutor, and so no dialectic is possible. Put differently, with Agamben, there is no vision of what victory would constitute or look like, and with Negri, the possibility of defeat never really enters the picture or the analysis. The role of ruling classes opposing the movements Negri theorizes, most usefully is his master work Potere costituente, translated into English and published by the University of Minnesota Press as Insurgencies, or that of the pre-existing state institutions in re-shaping the efforts of revolutionary movements plays no or little role in his otherwise often admirable work. And the role of movements for democratizing the state, ending or abolishing concrete historical forms of “homo sacer” such as slavery, Native American genocide, the worst oppressions of patriarchy, colonial occupations, child labor, the conditions of labor before the ten-hour and eight-hour movements and so on, do not play any role at all in Agamben’s work. Not even the European Resistance to the very Nazi occupations and states of exception that are the center of his view of the modern state makes an appearance.

In my article of ten years ago, and still today, I contrast these one-sided accounts with two other works, in my view more useful for our needs in the service of struggles today. One is that of Naomi Klein, in her bestseller Shock Doctrine, and the other is the work of Peter Linebaugh in his Magna Carta Manifesto. The dialectic in Klein’s work is that the struggles that gave rise to social democracy, the end of colonialism and apartheid, and to even the welfare state elements of Stalinist regimes are what capital is working to overcome through neoliberalism–privatization, deregulation, governance by central banks and openness to capital markets and global markets for goods. Since these policies are deeply unpopular, a state of emergency of some sort or another, permitting “shock therapy”–a swift reorganization of the economy in favor of capital, is needed. So Agamben’s states of exception are directly the result of the class struggle and a particular capitalist strategy to overcome working class, democratic and popular opposition. It happens because nothing else would enable the reforms that shift the balance of power in favor of capitalism. And it is needed, because capitalism finds itself in crisis or facing eventual crisis if profit rates cannot be increased through these neoliberal mechanisms.

For Linebaugh, our legal rights, our constitutional rights, have an economic basis in access to subsistence and in control of common lands and common goods. When these are expropriated, our legal rights do become, or risk becoming if a new form of class struggle does not emerge to protect them, merely the paper they are written on. Our rights and freedoms, which Agamben is so concerned about, always risk becoming dead letters, except when struggles and movements emerge to defend them, movements and struggles for whom the legal rights are tools. But movements and struggles for whom the real objective is the concrete meeting of needs and control over or access to common goods and resources we need for our lives, and guarantees and access to subsistence. These analyses by Linebaugh and Klein are light-years ahead of those of Agamben on the very question that tortures him and informs his whole body of work, because in each there is a dialectic at work–the struggle between capitalist forces and those of people defending their access to livelihoods and needs. The form of the state, its policies, and its institutions, and the balance of power between these in the formal constitutions of states–and in what Negri usefully calls the material constitutions–are both the outcome of, and themselves actors in these struggles.

Historic struggles against states of exception, be they antislavery or anticolonialism, the resistance to capitalist coups in Chile in 1973 (unsuccessful) or Venezuela in 2002 (successful) or Honduras or Brazil in recent years, or even the seizure of the Bastille by the people of Paris on July 14, 1789 to prevent Louis XVI’s attempt at a state of exception, all these are nowhere to be found in Agamben’s view of the world. Yet WE need to know about these cases, who the actors were, what they wanted and why, how and why they succeeded or failed.

Marxists Humanists and readers here of course, don’t need me to tell them how important to an analysis dialectics are, but I would like to show how lacking a dialectic in social and political analysis leads directly to Agamben’s disastrous current project of anti-vax, anti-public health measures in the face of a pandemic that has taken millions of lives around the world. The point is, that lack of a dialectic has been a central part of his work all along, and not only of his. So I will conclude after the analysis of Agamben’s accusations regarding Covid requirements with a comment on some other recently fashionable thinkers and political stances.

All Agamben has is a hammer: the state is bad, it is Nietzsche’s Will to Power personified, its “biopolitics” (Foucault) is deadly in nature and reduces us to bare life, naked homo sacer stripped of ethical, moral, legal and cultural features before it, requiring us to do everything for mere survival, especially now when it requires us to stay home, or get a vaccine, or wear a mask, or not interact with each other. As if this reduction of human being’s cultural and ethical characteristics to “mere worker”–a means to an end were not already a primary feature of capitalism as Marx showed as long ago as his manuscripts on Alienation in 1844. But Agamben’s state is entirely one-sided: it is only repression.

As Hal Draper showed in his monumental Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, the state takes on basic and necessary public functions–community collective defense, roads, schools, law and a judicial system–that will exist in any society or community of any kind–as paradoxically Graeber and Wengrow’s recent celebrated work The Dawn of Everything demonstrates. In a class society, however, the state, under the primary influence of the dominant class and defending its interests, will carry out these basic functions in a distorted way, in a way that both carries them out and enhances the wealth and power of the ruling class and the inequalities of wealth and power in society as whole, at least more often than not. When the two conflict, the struggle between classes, within the state and across society as a whole decides which will win out. The state’s legitimacy is bound up with its ability to carry out these essential functions for society, and its failure to do so can lead to it, or at least its leaders, losing the support of society’s larger membership, something that the Chinese “Mandate of Heaven” being lost due to inability to provide for people during famines, floods or earthquakes, the dangers to the Egyptian Pharaohs if they failed to organize the Nile flooding and agricultural adequately, and even George W. Bush’s failure to secure New Orleans from the Mississippi’s overflowing the levees, stand as examples of. So, there is a dialectic within the state: legitimate social functions versus state power qua ruling class power. And on the side of legitimate social functions stand the social and physical needs of the non-ruling class part of the population. This conflict is at least as old as Hammurabi’s Code, which both protected the poor, widows, orphans and slaves, and codified the class power and privilege of nobles. With the rise of democracy, this struggle becomes even more central, as structural and institutional pressure by popular forces are also written into the form and content of the state, even as capitalist power and dominance are as well. Thus, the dialectic inherent to the state in a class society is directly tied to the class struggle in society itself. With the rise of democracy, this dialectic is now written into the relationships between the institutions of the state themselves. Some agencies, institutions and actors lean toward basic social functions, and are more directly linked to and under the pressure of popular needs and demands. Others are more well-sheltered from popular pressure and democratic power–this is where Klein’s emphasis on the role of shifting decision-making to Central Banks for instance is important–leaning toward a more one-sided preoccupation with ruling class and capitalist interests.

Thus, during a crisis such as the Covid crisis, we should turn our attention to these dialectics–is capital taking advantage of a crisis to further its project of privatizing wealth and power and public policy?–an issue at the center of Klein’s work on “disaster capitalism” but nowhere to be found in Agamben; are capitalists profiting off the now vital and emergency needs of people in the face of a public health catastrophe? Are the restrictions that a basic and necessary social function of the state–the protection of society and its members in the face of a natural or public health disaster–designed and implemented in a way that is appropriate to the crisis and its resolution? Can the state act as an organizer of production and distribution of basic necessities such as medical products and implements, and if so, will it do so with an eye toward production for use or for exchange and capital accumulation? Are policies designed and implemented in ways that are fair and equitable and take into account the needs of various social actors–teachers and students and parents, workers and employers, health providers and patients, the marginalized and the majority, or are they clearly or subtly means of only favoring the interests of, and shifting of power to, employers, large firms versus small business, the rich and well-connected? These are the kinds of questions we need to, and have every right to ask.

But if instead one has no sense of these dialectics within and between the state, civil society and social classes and actors, then one cannot see the reality of the pandemic. To see the pandemic as real means to see that some public health measures are called for, as well as some changes in individual and collective behavior for the period of the crisis, realizing that merely because extreme measures are needed temporarily, they are not necessarily–and indeed are not intended–to be permanent. States of emergency over short-term natural disasters are a frequent occurrence, but are usually lifted as soon as the hurricane, flood, fire or earthquake is over or its consequences have been sufficiently cleaned up. At times public interest would be better served by prolonging states of emergency lifted too quickly in order to satisfy business interests. Other times, they are lifted too slowly, as the concerns of everyday people are not listened to and taken into account. And legitimate struggles and protests may ensue in these cases and sometimes do. Indeed, in some extreme cases, the state utterly fails in its social obligations and allows people to suffer from such emergencies without assuming emergency powers to help, or even doing so, but then not really helping. But if there is no such dialectic within the state as a complex entity, between legitimate public power in the service of social needs, and the distortion of these powers and their use due to the influence of dominant class interests and power, then all one sees is the bad state imposing its will. The pandemic itself has to be, according to the already existing logic of Agamben’s work, wished away as non-existent, since any emergency or crisis must be manufactured by the state as an excuse to impose a state of exception. And this is what Agamben claims, in ever-escalating and insulting rhetoric, is happening now and has been for the past two years.

Thus, Agamben refers to “The Invention of a Pandemic” (www.quodlibet.it ) in a widely-read article of February 2020, at the start of the Covid impact in Italy, which was the first country outside of China to have a major wave of Coronavirus cases. Comparing the virus to the flu, and downplaying its dangers, Agamben accused Italian media of “spreading a climate of panic”. He has more recently claimed in on Twitter that “Today in my country measures are applied against “anti-vaxxers” that are 10X (ten times) more restrictive than the fascist legislation of 1938 against ‘non-Aryans’” (twitter.com )– by which he means Mussolini’s anti-Semitic laws that led tens of thousands of Italian Jews to the death camps. A more insulting and false set of claims would be hard to imagine, and here Agamben’s rhetoric is at one with that of the American far right, not something we would expect from a supposedly left-wing philosopher. In November 2020 in a talk with students in Venice, Agamben claimed that these restrictions are bringing humanity “towards extinction–if not physical at least ethical and political”. (www.quodlibet.it). I would be tempted to suggest that Agamben, in clinging to his February 2020 view, based on early information and misinformation as to the real nature of the virus and its impact, is engaging in what Hegel termed “Understanding”–maintain rigid fidelity to categories based on old realities that they no longer explain under newer conditions. But for Hegel, Understanding did correspond to reality, was a right or least useful way of explaining or defining phenomena at one time at least. Instead, in the case of Agamben, all we have is what in Organizational Behavior is called “anchoring”–sticking with your initial way of understanding something that is happening, and not changing your view when more or new information comes about, because you have already made up your mind.

To claim that the efforts to stop the spread of, and reduce or end the fatalities it has caused and continues to cause lack ethical, political, moral, cultural, or even religious characteristics from a humanist point of view, as Agamben does, is sheer madness and falsehood. The vast majority of the population in every country has recognized the ethical need to vaccinate oneself and to wear masks and engage in social distancing. This reality is something we should find cause of hope and cautious optimism in–an affirmation of basic ethical concerns overriding even economic interests and needs. This extended even to the patience with which populations around the world accepted total or near total lockdowns–NOT as Agamben claims, because we are lemmings, an echo of the “sheeple” insult by the U.S. right to those who act to protect others and themselves, but out of a sense of ethics born of a sense of collective belonging and interdependence.

And though predictably capital has lobbied hard, used its influence and in general has done all it could as a class interest to reopen business, and to continue to have work done in very unsafe conditions, the majority around the world have made clear that they want workplaces and classrooms to be safe. In many cases, as in the mass refusal that has come to be known as the Great Resignation in the U.S. and UK, millions of workers have stayed home, quit jobs, or refused to take new ones if they are not satisfied as to the conditions, including the public health ones. In other words, most people–even if hardly unaware that government can be repressive or unfair or corrupt–are aware of the two-sidedness of the state–that in this case it is at least to a great extent acting in the legitimate public interest of protecting public health and lives. People get angry at corruption, but stop at traffic lights. There is a difference. Where people aside from the anti-vax minority have made demands, these have been completely legitimate demands that if one’s workplace or small business must shut down directly as a government policy, that compensation be made to keep people’s livelihoods protected; that parents needing to work at home have their privacy protected from employers; that schools be made safe and opened whenever possible, and so on. These demands reflect the clear understanding that the crisis must not be used to expropriate or exploit their work and small businesses by capital, while accepting the legitimate side of state policy in the public interest. Such demands led to job and payroll guarantees in Denmark, the UK and elsewhere and the–even if minimalist–direct payments by the U.S. government to citizens to provide some income, as well as rent and student debt moratoriums. Public pressure has led even to the Italian government’s distribution of small funds to certain categories of unprotected workers and self-employed people, and some job protections here. And in Italy and elsewhere demands were made on the EU to act as a legitimate public power and provide aid, materials for health care, and money to Eurozone countries that can’t produce their own currency, demanding in other words that it be more than a mere institutionalization of the power of finance capital.

What Agamben and others could usefully be doing instead is making clear the danger of the finally arriving EU funds to Italy being turned over primarily to the banks and large corporations and corrupt political organizations. The near-unanimous consensus among ruling class spokespeople is that former EU Central Bank President Mario Draghi, now Italy’s unelected prime minister is a genius, a wizard, the zeitgeist on a white horse. But his government seems determined to distribute the EU funds and most likely to the class forces that Draghi has represented all his professional life. Here indeed we have an example of the capitalist interests overriding, or seeking to override, the legitimate public functions of the state in a crisis. Draghi replaced a popular and elected government that, whatever its errors and failings had, under Giuseppe Conte, guided the country through the worst with palpable compassion and empathy, and with continual communication and responses to the public and press. the Draghi government has already lowered taxes on the very rich, and seems prepared to be the “executive committee of the bourgeoisie as a whole.” But even in this case, popular outrage was reflected in the decision of Italy’s parliament not to make Draghi the next President of the Republic, Italy’s head of state. To ignore popular struggles, to ignore the dialectics of society and state, will lead one into trouble every time. Agamben seems unconcerned with the real threats to democracy of technocratic governance in the interests of capital, on one side, and the rising and growing fascist threat–one that he is either knowingly or unwittingly feeding with his stance on Covid restrictions–on the other, and their mutual reinforcement. Instead, his attacks are on the legitimate role of the state in protecting public health and the ethical actions and legitimate class demands of the people. These latter are manifested most people abiding by the requirements of being vaccinated, and of having the “Green Pass” confirming one’s vaccination status as a requirement to be in public restaurants and on public transportation, and living with the requirements to wear masks and social distance. All while demanding that state policies meet economic needs arising from these restrictions, and not protect privileged sectors instead.

But Agamben should also, I believe, be seen in a wider context of a number of influential thinkers that sees the state as the main, indeed usually the only threat to liberty and human well-being, to the exclusion of the dynamics of capitalism, or at least playing down the role of the latter. Each of these has a one-sided view of the state, based either loosely, or closely, either unconsciously and indirectly or consciously and directly on the ahistorical Nietzschean will to power, or on a one-sided view of the state as entirely and exclusively capitalist in form and content. This field stretches from Foucault’s biopolitics with its concern about the state being ever more involved in questions of health care, science, housing, employment and livelihoods with the rise of the welfare states, a view that deeply informs Agamben’s, to John Holloway’s call to avoid the state at all costs as an entirely capitalist enterprise, and to change society exclusively by not taking power, to Guattari and Deleuze’s writings that ignore the longest part of human history of hunters and gatherers and egalitarian societies, but then go on to theorize state power ahistorically on the basis of the questionable category “nomadism”, to Raul Zibechi’s writings on Latin American social movements, James Scott’s anthropology of grain-based societies, and Graeber and Wengrow’s recent bestseller. All see the state as only bad. A default anarchism has taken hold of a considerable part of the intellectual left in recent years and while we must gain what we can from the insights that these present us with, we need to see that such one-sidedness, such lack of dialectic, can only lead one to grave errors. Agamben has not gone mad recently, his work was always flawed, and he is not alone. We need better theoretical ways of understanding what is happening, and the ways things are; ones that see the all-sidedness of crises, struggles, states, societies, institutions and ideas, that can grasp what Marx called “the ensemble of social relations”. We can only hope that those who have instead decided to guide themselves by such deeply wrong ideas about ethics, public health and public authority, democracy and freedom, will not lose their lives in the process to this still dangerous and terrible pandemic is indeed very real, nor cost the lives of others.

Addendum: As I was writing this article, the crisis in Canada grew, such that, on Saturday February 6, 2022, the mayor of the capital city of Ottawa declared a state of emergency, in response to a blockade and mass occupation of the city’s streets by mostly self-employed truckers and right wing, including openly neo-Nazi militants, protesting requirements that truckers entering the country from the United States, where Covid remains rampant, and other public health measures, including mask wearing. The protesters have been threatening and harassing neighborhood residents, entering shops maskless en masse, forcing many to remain shut and essentially keeping a large part of the population of the nation’s capital hostages, shut up in their homes fearing for their safety. The protests have spread to Quebec City and Toronto. For Agamben, the danger is the declaration of a state of emergency. In reality, the danger, to the health and physical safety of the people living in these cities, and to Canadian democracy and the freedoms enjoyed by Canada’s people, is to the very forces Agamben now justifies openly, and with whom his analysis was always in danger of justifying: the fascists threat of a few thousand aggressive and violent activists who demand a right to put the lives of others in danger, the right to have no concern for the lives and safety of others, and who refuse even the most innocuous limits on their personal license and activities, regardless of the consequences for other people or for society. Just as in the time of Lincoln and the U.S. Civil War, a state of emergency is the recognition of reality: a genuine threat to democratic government that needs to be addressed by organized self-defense of society by society, a concept lacking in Agamben, and most of the other thinkers criticized above.

The people of Canada, or anywhere else, we, have a right to resist this will to power by a fascist minority, through collective struggle, through the use of law and institutions, through self-organization, and yes, if necessary through the use of force organized collectively in democratic states and public authorities in defense of democracy and of our collective lives and well-being. That is no state of exception, that is legitimate popular government. And if we need to go beyond it to an even more democratic, more egalitarian system, we will do so while dialectically maintaining the good in what we have already won through centuries of popular struggle, or not at all.

Notes:

- ↩ Available through the following sites: www.jceps.com ; www.academia.edu