It has become common, in recent years, to hear assertions that the world is already in the midst of a transition to a green economy. A prominent example from Australia is billionaire iron ore magnate and recent convert to “green hydrogen” Andrew Forrest, who recently claimed that “the journey to replace fossil fuels with green energy … is now violently on the move”. This kind of “green triumphalism”, however, is little more than a fantasy—one that is (and often consciously intended to be) a barrier to winning the kind of radical change we need.

It’s understandable that some would believe a “green transition” is underway. After all, we’re constantly bombarded with propaganda to that effect. These days it’s no longer viable for the rich and powerful and their political servants simply to deny the reality of climate change and other environmental challenges. The new fad is to talk up whatever (inevitably small-scale) green initiatives are happening, and spruik the array of magical technological fixes that, like Forrest’s beloved “green hydrogen”, are always somehow just on the verge of taking off.

The propagandists of the “green transition” point to rapid increases in global investment in renewable energy and other green technologies over the past decade or so. And when you look at the raw numbers, they appear to provide some backing for the argument. Global investment in renewables was projected by the International Energy Agency (IEA) to come in at US$367 billion in 2021—up from $359 billion in 2020 and $336 billion in 2019. That’s a lot of new wind turbines, solar panels and hydroelectric power stations.

Those figures alone, however, are far from telling the whole story. The $367 billion investment in renewables in 2021 has to be seen in the context of the $1.9 trillion the IEA estimates was spent globally on energy production as a whole, a figure that includes $813 billion specifically on fossil fuels.

This points to a problem that quickly becomes apparent when you look at the relative position of fossil fuels and renewables in the global energy mix over time. The portion of energy coming from renewables has increased—from 6.6 percent in 1990, when climate change was first gaining serious attention, to 8.8 percent in 2010 and 12 percent in 2020. But a 5.4 percent increase over three decades, including only a slight acceleration to 3.2 percent in the decade to 2020, is hardly the kind of “transition” that scientists think is necessary to avoid runaway warming. If we continue at the current rate, the portion of renewables in the global energy mix will still be only just over 20 percent in 2050.

The reason for this slow progress is clear. While renewable energy production has grown significantly in the past 30 years, so too has the fossil fuel industry. In 1990, total global energy production from fossil fuels was 83,048 terawatt-hours (TWh). In 2019, before the artificial dip in production caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health measures, it was 136,131 TWh—an increase of 64 percent. The production of renewable energy has increased at a faster pace—rising from 6,226 TWh in 1990 to 17,466 TWh in 2019. Because it comes from such a low base, however, this 180 percent jump has had very little impact on overall global emissions.

A report by the IEA published in early March—Global Energy Review: CO2 Emissions in 2021—shows clearly why increasing investment in renewable energy alone doesn’t make a genuine “green transition”. The report found that in 2021 total global CO2 emissions rose at a record pace of 6 percent to a new high of 36.3 billion tonnes, despite, at the same time, “renewable power generation registering its largest ever growth”.

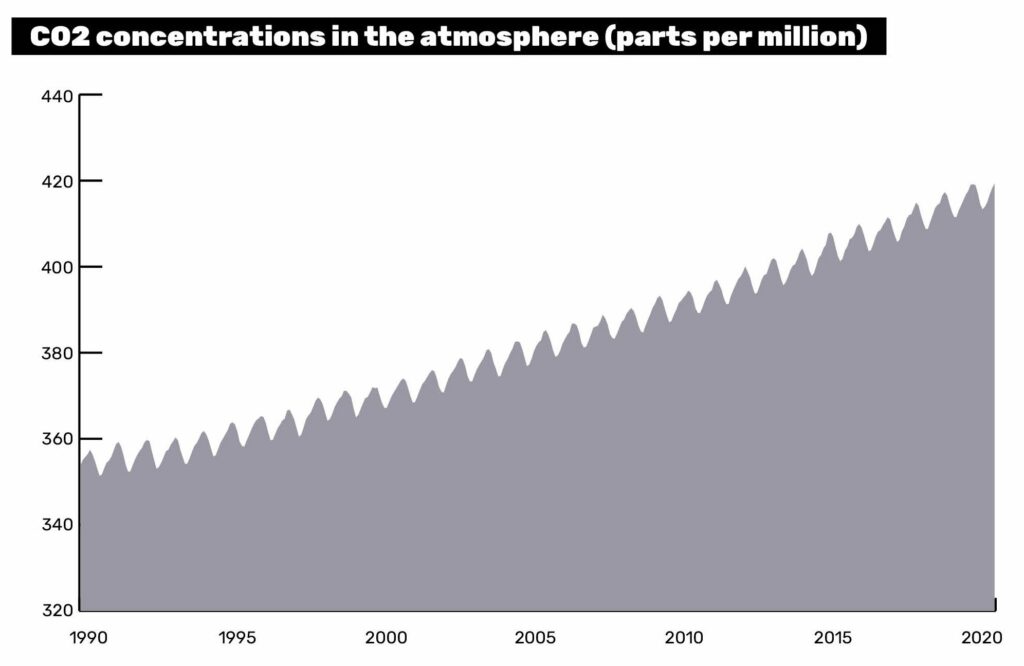

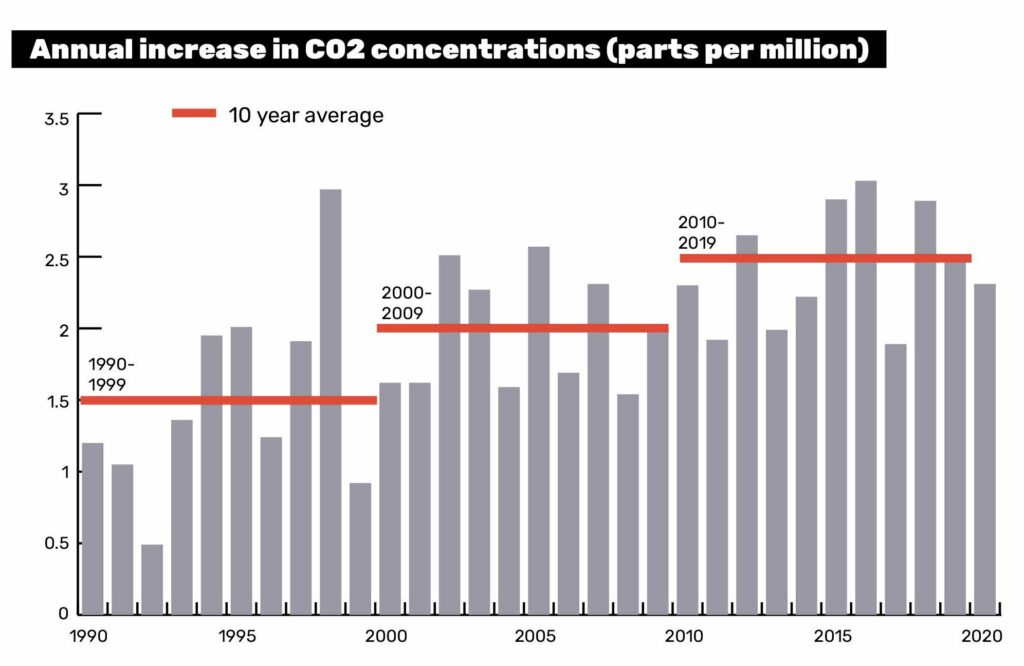

Perhaps the best way to judge whether a “green transition” is underway, however, is to look at concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The data on this is much more reliable than countries’ self-reported emissions, which are often the product of some highly dubious accounting methods. It’s the figures on concentrations of CO2 and methane in the atmosphere that show most clearly the disconnect between the increasing amount of green rhetoric from politicians and business leaders, and the unfortunately very gloomy reality.

If the “green transition” spruikers are to be believed, we’ve been heading in the right direction for some time now. Yet not only have overall concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere not ceased their relentless rise since the dawn of the age of “climate ambition” in the early 1990s, the rate of increase has been gradually accelerating.

According to measurements made by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration at Mauna Loa in Hawaii, the average concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere in 2021 was 416 parts per million (ppm). This compares to 354 ppm in 1990, 370 ppm in 2000 and 390 ppm in 2010. Over the same period the rate of annual increase has risen from an average of 1.5 ppm in the 1990s, to 2 ppm in the 2000s, to 2.4 ppm in the 2010s.

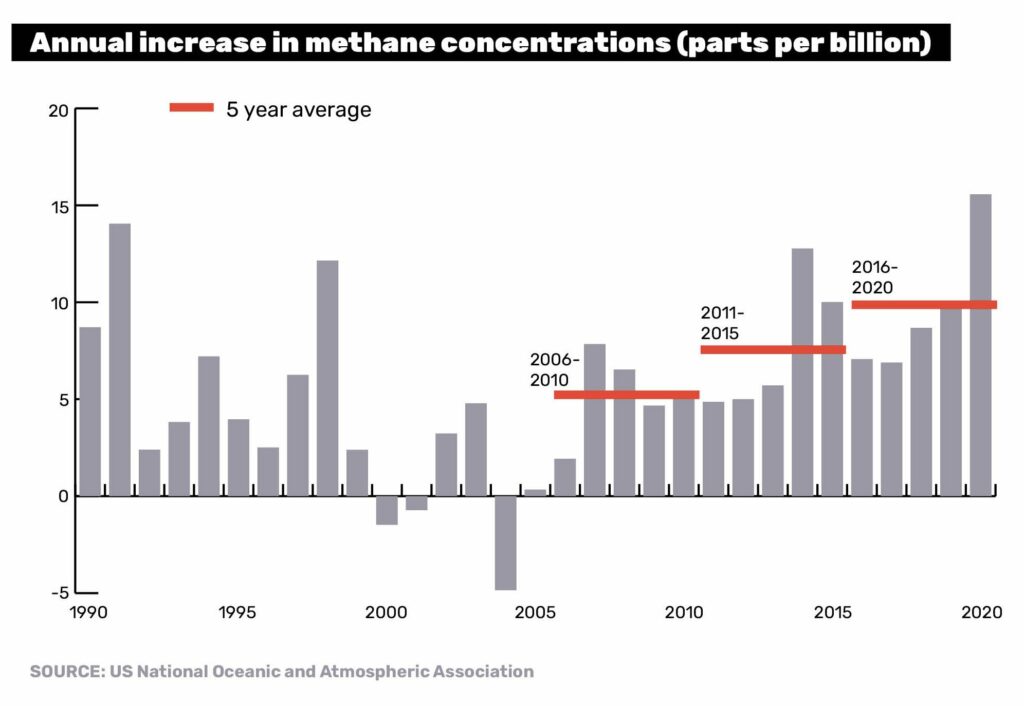

When concentrations of methane—a much more potent driver of warming, in the short term, than CO2—are added to this, the situation looks dire indeed. Atmospheric methane concentrations stalled for a period in the early 2000s, but since around 2007 they have been rising rapidly. The concentration of methane in the atmosphere sat at 1,909 parts per billion (ppb) in November 2021, up from 1,774 ppb in 2005. Over that period, the average rate of annual increase has risen from 5.2 ppb in the five years from 2006, to 7.7 ppb from 2011 to 2016 and 9.6 ppb from 2016 to today.

It’s hard to take talk of a “green transition” seriously when both the total volume of emissions, and the rate of increase in concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, continue to hit new highs. Until those numbers start to come down, we should be very suspicious of anyone making claims about the wonderful world of green capitalism we’re supposedly on our way to. No doubt many such people are simply naive, but there are certainly some among them who are quite conscious of the role their pronouncements play in greenwashing the dirty reality of capitalism’s ongoing addiction to fossil fuels.

All this was true before the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In the new situation created by the war, the reasons to be hopeful about the world’s efforts to tackle the climate crisis are, unfortunately, even fewer. There was no real “green transition” underway before the war, and now there’s even less of one.

The invasion and the economic sanctions imposed on Russia by the West in response have triggered massive increases in the price of oil, coal and gas. Climate and environmental activists have expressed hope that this may reinforce the need for an accelerated shift to renewable energy. In the short term, though, it seems more likely to trigger a race to expand fossil fuel production by the Western powers.

Elon Musk—a hero of some of the more obnoxious green-tech-focused “environmentalists”—was typical of the wider sentiment. “Hate to say it”, he tweeted on 5 March, “but we need to increase oil & gas output immediately. Extraordinary times demand extraordinary measures”.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson indicated that Britain may increase domestic gas and oil production from the North Sea to make up the shortfall of what it had previously imported from Russia. “One of the things we are looking at”, he said, “is the possibility of using more of our own hydrocarbons … We have got to reflect the reality that there is a crunch on at the moment. We need to intensify our self-reliance as a transition with more hydrocarbons”.

In Germany, economy minister Robert Habeck, a member of the Greens, was reported by the Financial Times to have said that “Europe may be forced to burn more coal in the face of Russian aggression and spiralling gas prices”. Pressure is also building on US President Joe Biden to support a rapid expansion of fossil fuel production there, despite the fact that, unlike European countries such as Britain and Germany, the US hasn’t been a major customer for Russian oil and gas.

Executives at the world’s major fossil fuel companies are rubbing their hands with glee. Rising demand for coal in 2021 had already boosted profits, leading some companies to make expansion plans. Those plans, it seems likely, will now be accelerated. And Australia’s fossil fuel industry—one of the world’s largest—will be among the main beneficiaries. The Australian government was already planning a massive expansion of our already booming gas industry. We can expect the new situation to further encourage it in this.

Will all this just be a minor speed bump in the road to a greener future? No doubt that’s how our leaders are going to spin it. But we should remember that a significant expansion of fossil fuel production isn’t something that can be easily unwound if and when the “extraordinary times” created by Russia’s invasion end.

The development of new infrastructure for the extraction, processing and distribution of fossil fuels costs a lot of money. And the companies involved (and the governments of the countries in which they are based) are unlikely to accept that their investments will have to be written off if and when the (supposed) “green transition” resumes. They will, rather, keep doing what they’ve been doing for decades—working hard to delay climate action as long as possible so they can squeeze out every last drop of profit possible.

The one hope remains that people won’t fall for the propaganda about a non-existent “green transition”, and that they will continue to fight the fossil fuel barons and their political servants every step of the way. Put simply, there can be no genuine “green transition” in a system like capitalism that’s defined by the endless, competitive pursuit of profit and growth, and by all the various destructive tendencies—whether those impacting on the environment, or those, as we’re seeing in Ukraine, of war—that inevitably accompany that.