Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

The war in Ukraine has focused attention on the shifts taking place in the world order. Russia’s military intervention has been met with sanctions from the West as well as with the transport of arms and mercenaries to Ukraine. These sanctions will have a major impact on the Russian economy as well as the Central Asian states, but they will also negatively impact the European population who will see energy and food prices rise further. Until now, the West has decided not to intervene with direct military force or to try and establish a ‘no-fly zone’. It is recognised, sanely, that such an intervention could escalate into a full-scale war between the United States and Russia, the consequences of which are unthinkable given the nuclear weapons capacities of both countries. Short of any other kind of response, the West–as with the Russian intervention in Syria in 2015–has had to accept Moscow’s actions.

To understand the current global situation, here are six theses about the establishment of the U.S.-shaped world order from 1990 to the current fragility of that order in the face of growing Russian and Chinese power. These theses are drawn from our analysis in dossier no. 36 (January 2021), Twilight: The Erosion of U.S. Control and the Multipolar Future; they are intended for discussion and so feedback on them is very welcome.

Thesis One: Unipolarity. Following the fall of the Soviet Union, between 1990 and 2013–15, the United States developed a world system that benefitted multinational corporations based in the United States and in the other G7 countries (Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Canada). The events that defined overwhelming U.S. power were the invasions of Iraq (1991) and Yugoslavia (1999) as well as the creation of the World Trade Organisation (1994). Russia, weakened by the collapse of the USSR, sought entry into this system by joining the G7 and collaborating with the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) as a ‘Partner for Peace’. Meanwhile, China, under presidents Jiang Zemin (1993–2003) and Hu Jintao (2003–2013), played a careful game by inserting its labour into the U.S.-dominated global system and not challenging the U.S. in its operations.

Thesis Two: Signal Crisis. The U.S. overreached its power through two dynamics: first, by overleveraging its own domestic economy (overleveraged banks, higher non-productive assets than productive assets); and second, by trying to fight several wars at the same time (Afghanistan, Iraq, Sahel) during the first two decades of the 21st century. The signal crises for the weakness of U.S. power were illustrated by the invasion of Iraq (2003) and the debacle of that war for U.S. power projection, and the credit crisis (2007–08). Internal political polarisation in the U.S. and a crisis of legitimacy in Europe followed these developments.

Thesis Three: Sino-Russian Emergence. By the second decade of the 2000s, for different reasons, both China and Russia emerged from their relative dormancy.

China’s emergence has two legs:

- China’s domestic economy. China built up massive trade surpluses and, alongside these, it built up scientific and technological knowledge through its trade agreements and its investment in higher education. Chinese firms in robotics, high-tech, high-speed rail, and green energy leapfrogged over Western firms.

- China’s external relations. In 2013, China announced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which proposed an alternative to the U.S.-driven International Monetary Fund’s development and trade agenda. The BRI extended out of Asia into Europe as well as into Africa and Latin America.

Russia emerged on two legs as well:

- Russia’s domestic economy. President Vladimir Putin fought some sections of the large capitalists to assert state control of key commodity export sectors and used these to build up state assets (notably oil and gas). Rather than merely leech Russian assets for their overseas bank accounts, these Russian capitalists agreed to subordinate part of their ambitions to rebuilding the power and influence of the Russian state.

- Russia’s external relations. Since 2007, Russia began to edge away from the Western global agenda and drive its own project, first through the BRICS (Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa) agenda and then later through increasingly close relations with China. Russia leveraged its export of energy to assert control of its borders, which it had not done when NATO expanded in 2004 to absorb seven countries that are near its western boundary. Russian intervention into Crimea (2014) and Syria (2015) used its military force to create a shield around its warm water ports in Sebastopol (Crimea) and Tartus (Syria). This was the first military challenge to the U.S. since 1990.

In this period, China and Russia deepened their cooperation in all fields.

Thesis Four: Global Monroe Doctrine. The United States took its 1823 Monroe Doctrine (that asserted its control over the Americas) global and proposed in this post-Soviet era that the entire world was its dominion. It began to push back against the assertion of China (Obama’s Pivot to Asia) and Russia (Russiagate and Ukraine). This New Cold War driven by the U.S., which includes hybrid warfare through sanctions against thirty countries such as Iran and Venezuela, has destabilised the world.

Thesis Five: Confrontations. The confrontations hastened by the New Cold War have inflamed the situation in Asia–where the Taiwan Strait remains a hot zone–and in Latin America–where the United States attempted to create a hot war in Venezuela (and attempted but failed to project its power in places such as Bolivia). The current conflict in Ukraine–which has its origins in many factors, including the demise of the Ukrainian pluri-national compact–is also over the question of European independence. The U.S. has used ‘Global NATO’ as a Trojan horse to exercise its power over Europe and keep it subordinated to U.S. interests even if it harms Europeans as they lose energy supply and natural gas for the food economy. Russia violated the territorial sovereignty of Ukraine, but NATO created some of the conditions which accelerated this confrontation–not for Ukraine but for its project in Europe.

Thesis Six: Terminal Crisis. Fragility is the key to understanding U.S. power today. It has not declined dramatically, nor does it remain unscathed. There are three sources of U.S. power that are relatively untouched:

- Overwhelming Military Power. The United States remains the only country in the world that is able to bomb any of the other UN member states into the stone age.

- The Dollar-Wall Street-IMF regime. Due to the global reliance on the dollar and to the dollar-denominated global financial system, the U.S. can wield its sanctions as a weapon of war to weaken countries at its whim.

- Informational Power. No country has as decisive control over the internet, both its physical infrastructure and its near monopoly companies (such as Facebook and YouTube, which remove any content and any provider at will); no country has as much control over the shaping of world news due to the power of its wire services (Reuters and the Associated Press) as well as the major news networks (such as CNN).

There are other sources of U.S. power that are deeply weakened, such as its political landscape, which is deeply polarised, and its inability to marshal its resources to send China and Russia back inside their borders.

People’s movements need to grow our own power, by organising the people into powerful organisations and around a programme that has the capacity to both answer the immediate problems of our time and the long-term question of how to transition to a system that can transcend the apartheids of our time: food apartheid, medical apartheid, education apartheid, and money apartheid. To transcend these apartheids leads us out of this capitalist system to socialism.

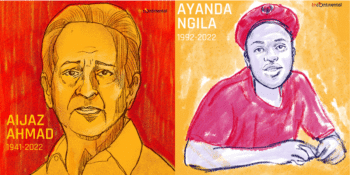

In the past week, we have lost many comrades, old and young. Amongst them, our Senior Fellow Aijaz Ahmad (1941–2022), one of the great Marxists of our time, left us at the age of 81. When Marxism was under attack after the fall of the USSR, Aijaz held the line, teaching generations of us about the necessity of Marxist theory; that theory remains necessary because it continues to be the most powerful critique of capitalism and, as long as capitalism continues to structure our lives, that critique remains boundless. For us at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Aijaz’s mentorship was invaluable. In fact, the dossier Twilight, which helped us orient ourselves in the current conjuncture, was written after substantial discussion with Aijaz.

We also lost Ayanda Ngila (1992–2022), who was the deputy chairperson of eKhenana land occupation, part of South Africa’s militant shack dwellers movement, Abahlali baseMjondolo (AbM). Ayanda was a courageous leader of AbM who had recently been released from a second spell of being held in prison on trumped up charges. He was a kind comrade to his peers and a student and teacher at the Frantz Fanon School. When he was gunned down by his adversaries in the African National Congress, Ayanda was wearing a t-shirt with a quote from Steve Biko: ‘It’s better to die for an idea that is going to live than to live for an idea that is going to die’. On the walls of the Frantz Fanon School, the comrades at AbM painted their ideals clearly: Land, Decent Housing, Dignity, Freedom, and Socialism.

We also lost Ayanda Ngila (1992–2022), who was the deputy chairperson of eKhenana land occupation, part of South Africa’s militant shack dwellers movement, Abahlali baseMjondolo (AbM). Ayanda was a courageous leader of AbM who had recently been released from a second spell of being held in prison on trumped up charges. He was a kind comrade to his peers and a student and teacher at the Frantz Fanon School. When he was gunned down by his adversaries in the African National Congress, Ayanda was wearing a t-shirt with a quote from Steve Biko: ‘It’s better to die for an idea that is going to live than to live for an idea that is going to die’. On the walls of the Frantz Fanon School, the comrades at AbM painted their ideals clearly: Land, Decent Housing, Dignity, Freedom, and Socialism.

We concur. So would Aijaz.

Warmly,

Vijay