Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Uzo Egonu (Nigeria), Stateless People, An Assembly, 1982.

The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) reports that, every minute, a child is pushed into hunger in fifteen countries most ravaged by the global food crisis. Twelve of these fifteen countries are in Africa (from Burkina Faso to Sudan), one is in the Caribbean (Haiti), and two are in Asia (Afghanistan and Yemen). Wars without end have degraded the ability of the state institutions in these countries to manage cascading crises of debt and unemployment, inflation and poverty. Joining the two Asian countries are the states that make up the Sahel region of Africa (especially Mali and Niger), where the levels of hunger are now almost out of control. As if the situation were not sufficiently dire, an earthquake struck Afghanistan last week, killing over a thousand people–yet another devastating blow to a society where 93% of the population has slipped into hunger.

In these crisis-hit countries, food aid has come from governments and the UN’s World Food Programme (WFP). Millions of refugees in these countries are almost entirely reliant upon UN agencies. The WFP provides ready-to-use therapeutic food, which is a food paste made of butter, peanuts, powdered milk, sugar, vegetable oil, and vitamins. Over the next six months, the cost of these ingredients is projected to rise by up to 16%, which is why on 20 June, the WFP announced that it would cut rations by 50%. This cut will impact three of every four refugees in East Africa, where about five million refugees live. ‘We are now seeing the tinderbox of conditions for extreme levels of child wasting begin to catch fire’, said UNICEF Executive Director Catherine Russell.

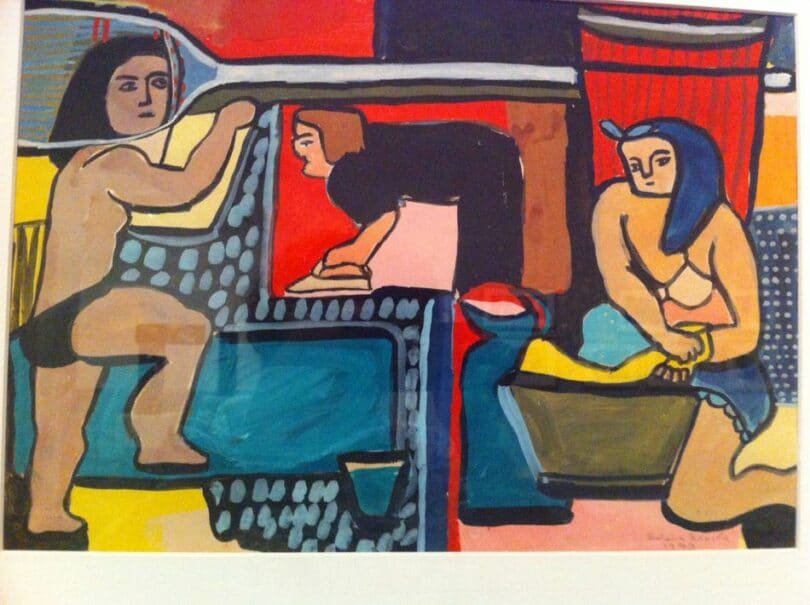

Yolanda Váldes Rementería (Mexico), Diversidad (‘Diversity’), 2009.

Clearly, the spike in hunger is related to the food price inflation, which itself has been exacerbated by the conflict in Ukraine. Russia and Ukraine are the world’s leading exporters of barley, corn, rapeseed, sunflower seed, sunflower oil, and wheat, as well as fertilisers. While the war has been catastrophic for world food prices, it is an error to see the war as the cause of the spike. World food prices began to rise about twenty years ago, and then went out of control in 2021 for a range of reasons, including:

- During the pandemic, the severe lockdowns inside countries and at their borders led to major disruptions in the movement of migrant labour. It is by now well-established that migrant labour–including refugees and asylum seekers–plays a key role in agricultural production. Anti-immigrant sentiment and the lockdowns have created a long-term problem on large-scale farms.

- A consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic was the breakdown of the supply chain. As China–the epicentre of a considerable volume of global manufacturing–pursued a zero-COVID policy, this set in motion a cascading problem for international shipping; with the lockdowns, ports closed and ships remained at sea for months on end. The return of international shipping to near normalcy and the return of industrial production–including fertilisers and food–has been slow. Food supply chains withered due to the logistics problems, but also due to staff shortages at processing plants.

- Extreme weather events have played a major role in the chaos of the food system. In the past decade, between 80 and 90% of natural disasters have been due to droughts, floods, or severe storms. Meanwhile, over the past forty years, the planet has lost 12 million hectares of arable land each year to drought and desertification; during this period, we have also lost a third of our arable land to erosion or pollution.

- Over the past forty years, global meat consumption (mostly poultry) increased dramatically, with the increases set to continue rising despite some indications that we have reached ‘peak meat consumption’. Meat production has an enormous environmental footprint: 57% of total emissions from agriculture come from meat, while livestock production takes up 77% of the planet’s agricultural land (even though meat only contributes 18% of the global calorie supply).

The world food market was already stressed before the conflict in Ukraine, with prices going up during the pandemic to levels that many countries had not seen before. However, the war has almost broken this weakened food system. The most significant problem is in the world fertiliser market, which was resilient during the pandemic but is now in a crisis: Russia and Ukraine export 28% of nitrogen and phosphorus fertiliser as well as 40% of the world’s exports of potash, while Russia by itself exports 48% of the world’s ammonium nitrate and 11% of the world’s urea. Cuts in fertiliser use by agriculturalists will lead to lower crop yields in the future unless farmers and farm companies are willing to switch to biofertilisers. Due to the uncertainty of the food market, many countries have established export restrictions, which further exacerbates the hunger crisis in countries that are not self-sufficient in food production.

Despite all the conversations on self-sufficiency in food production, studies show that action is lacking. By the end of the 21st century, we are being told, 141 countries in the world will not be self-sufficient and food production will not meet the nutritional demands of 9.8 out of the 15.6 billion people projected to be on the planet. Only 14% of the world’s states will be self-sufficient, with Russia, Thailand, and Eastern Europe as the leading producers of grain for the world. Such a bleak forecast demands that we radically transform the world food system; a provisional set of demands is listed in A Plan to Save the Planet, developed by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and the Network of Research Institutes.

In the short-term, UN Secretary-General António Guterres has made it clear that the conflict in Ukraine and the sanctions against Russia must be ended so that these key producers of food and fertiliser can resume production for the world market.

In the short-term, UN Secretary-General António Guterres has made it clear that the conflict in Ukraine and the sanctions against Russia must be ended so that these key producers of food and fertiliser can resume production for the world market.

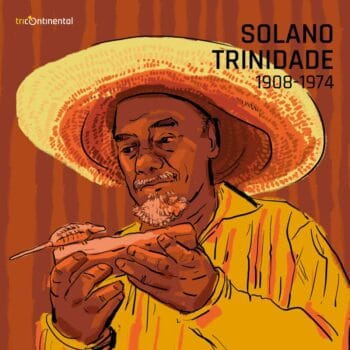

A recent study conducted by the Brazilian Research Network on Food and Nutrition Sovereignty and Security (Rede Penssan) notes that nearly 60% of Brazilian families do not have access to adequate food. Of the country’s 212 million people, the number of those who have nothing to eat has leapt from 19 million to 33.1 million since 2020. ‘The economic policies chosen by the government and the reckless management of the pandemic lead to the even more scandalous increase in social inequality and hunger in our country’, said Ana Maria Segall, a medical epidemiologist at Rede Penssan. But, only a few years ago, the United Nations championed Brazil’s Fome Zero and Bolsa Família programmes, which cut hunger and poverty rates dramatically. Under the leadership of former presidents Lula da Silva (2003–2010) and Dilma Rousseff (2011–2016), Brazil met the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. The governments that followed of Michel Temer (2016–2018) and Jair Bolsonaro (2019–present) have reversed these gains and brought Brazil back to the worst days of hunger, when the poet and singer Solano Trindade sang, ‘tem gente com fome’ (‘there are hungry people’):

there are hungry people

there are hungry people

there are hungry people…

if there are hungry people

give them something to eat

if there are hungry people

give them something to eat

if there are hungry people

give them something to eat

Warmly,

Vijay