Coinbase recently filed its interim financial report. It makes pretty grim reading. A quarterly net loss of over $1bn, net cash drain of £4.6bn in 6 months, fair value losses of over 600k… To be sure, Coinbase is not on its knees yet. It still has $12bn of its own and customers’ cash (both are on its balance sheet), and a whopping asset base. In fact its assets have increased–a lot. As have its liabilities. Coinbase’s balance sheet is five times bigger than it was in December 2021.

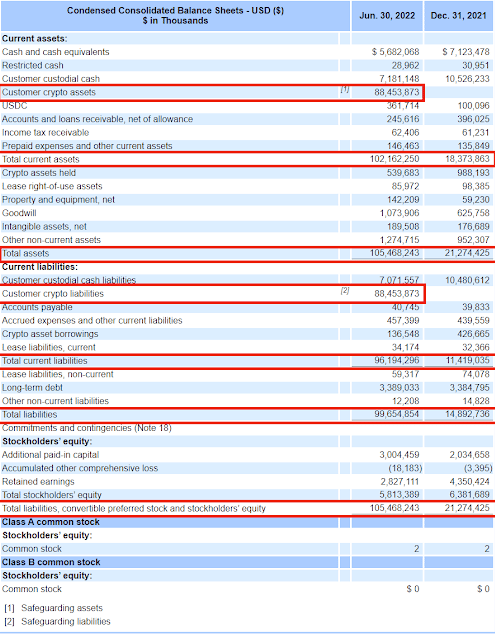

Here’s Coinbase’s balance sheet, as reported in its 10-Q filing. I’ve outlined the relevant items in red:

There’s a new asset called “customer crypto assets” worth some $88.45 bn, matched by a new liability called “crypto asset liabilities”. This asset and its associated liability are by far the biggest items on Coinbase’s balance sheet. Footnotes to the balance sheet describe these new items as “safeguarding assets” and “safeguarding liabilities”.

A note to the financial statements explains that as of June 2022, Coinbase has taken all customer assets on to its own balance sheet. It was already recording customer cash balances on its balance sheet, but now it is also recording customer crypto holdings. The size of the “safeguarding” liability is far too large for it to represent assets in Coinbase’s custody service. It must include assets in ordinary wallets. So Coinbase is no longer simply hosting wallets and providing a platform for peer-to-peer transactions. It is taking custodial responsibility for every customer asset on its platform.

But why this sudden change in the accounting treatment of customer crypto assets? Six months ago, they weren’t even on its balance sheet.

The explanation is in the same note (my emphasis):

The Company safeguards crypto assets for customers in digital wallets and portions of cryptographic keys necessary to access crypto assets on the Company’s platform. The Company safeguards these assets and/or keys and is obligated to safeguard them from loss, theft, or other misuse. The Company records Customer crypto assets as well as corresponding Customer crypto liabilities, in accordance with recently adopted guidance, SAB 121.

So this is at the behest of the SEC. SAB 121 is a Staff Accounting Bulletin issued in March 2022. It’s complex, technical and not easy to read. It’s also very wide-ranging and has far-reaching implications not only for crypto exchanges like Coinbase, but for any company providing crypto-related services involving public blockchains. Yet it seems to have passed unnoticed by the crypto and financial press. How it slipped under the radar is a mystery.

SAB 121 (footnote 3) defines “crypto assets” broadly:

the term “crypto-asset” refers to a digital asset that is issued and/or transferred using distributed ledger or blockchain technology using cryptographic techniques.

That could mean anything on a blockchain. Crowe LLP’s handy explainer lists four types of crypto asset it thinks will be affected by this change:

- Crypto assets used as a medium of exchange (for example, bitcoin)

- Stablecoins (for example, a digital asset that is backed 1:1 to the U.S. dollar)

- NFTs;

- Utility tokens

This list is not exhaustive. It would be unwise of a crypto company to think that because some asset doesn’t strictly fall into any of the categories above, it wouldn’t need to be treated in the same way.

What defines whether assets fall under the scope of SAB 121 is not the nature of the assets, but the nature of the relationship with the customer. The SEC says platforms providing transaction services to crypto asset holders are responsible for protecting the platform user’s crypto-assets from loss or theft, and to this end, often maintain the keys needed to access the assets. This creates risks unique to crypto asset transaction services:

Technological risks include such things as hard forks, hacking, multisig failures, “configuration issues” and bugs in the code. The terms of service of crypto exchanges and platforms nearly always contain a clause saying “we are not liable for any of these”, but it seems the SEC disagrees.

Legal and regulatory risks arise from the fact that crypto is a relatively new field in which the legal and regulatory frameworks are as yet unclear. The legal risks are particularly interesting in the light of Coinbase’s admission that customer cash on its balance sheet might not be bankruptcy remote, and the uncertainty over the status of both cash and crypto assets in certain high-profile crypto platform failures.

The SEC, it seems, is not satisfied that keeping customer assets off the platform’s own balance sheet and those of its agents necessarily means the assets are either bankruptcy remote or protected from fraud, theft, technological failure or other losses beyond the customer’s control. So, in the interests of protecting customers from these risks, it has simply decided to make the platforms and their agents liable for everything. The new accounting guidance says that the companies must carry on their own balance sheets a “safeguarding liability” equal to total customer crypto assets at fair value. So if anything happens to those crypto assets, the company, not the customer, will bear the losses.

Furthermore, to ensure that customers can always be reimbursed for any losses due to hacking, security failures, bugs, fraud and so forth, the companies must also carry a “safeguarding asset” whose fair value is equal to the fair value of the liability. In effect, the SEC is requiring 100% reserving of customer crypto assets. And to discourage crypto platforms and their agents from leveraging up the safeguarding liability by diversifying the safeguarding asset into a riskier mix of assets, thus putting customers at risk of losses, SAB 121 says that if the fair value of the safeguarding asset falls below the fair value of the liability, the company must take the fair value loss through its own P&L.

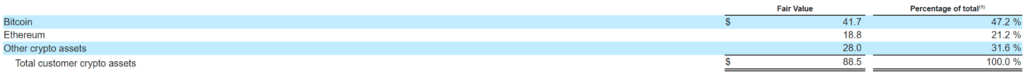

To show how this works, here’s Coinbase’s breakdown of its customer crypto assets at fair value as at June 2022:

This means that its “safeguarding liability” is made up of 47.2% BTC, 21.2% ETH and 31.6% other coins. To be fully insulated from fair value losses, the “safeguarding asset” must be made up of the exact same proportions of BTC, ETH and other coins. But the “safeguarding asset” is Coinbase’s own asset, not a customer asset. So, Coinbase could decide to reduce the proportion of low-yielding BTC and increase the proportion of higher-yielding but riskier coins. In a crypto market crash, the market price of riskier coins would be likely to fall more than the market price of BTC, so the fair value of Coinbase’s “safeguarding asset” would fall below that of the “safeguarding liability”. Coinbase would have to take that fair value loss directly to its own P&L, rather than dumping it on its customers by haircutting their assets. I hope this makes sense.

SAB 121 does not only apply to customer assets formally held by the exchange or platform as custodian. It also applies to assets in “hot” wallets to which the exchange or platform holds the key. That, as the crypto exchange Gemini explains (my emphasis), is pretty much all assets on crypto exchanges:

If you buy cryptocurrency on a crypto exchange, it is immediately stored in your exchange-hosted wallet where, typically, the exchange controls your private key.

It will also apply to assets on other crypto platforms.

The new accounting guidance takes effect from 15th June 2022. Coinbase therefore reported its end of June half-year results under the new guidance. Other exchanges will follow suit when their accounts fall due, and so too should other crypto platforms that host customer assets to which they control the keys. No doubt some will think up all manner of reasons why they shouldn’t have to, and others will simply not bother and hope to get away with it, but we should nevertheless expect to see a swathe of massively inflated balance sheets in the next few months.

The accounting itself is simple enough. But the implications for exchanges and platforms are far-reaching. No longer can the costs of hacks, security failures, bugs and exploits, rug pulls, scams and frauds be dumped on customers by means of coercive deposit haircuts and token issuance. Exchanges and platforms will have to hold sufficient crypto assets of the right quality to be able to reimburse customers for any and all losses from events like these. And if there is a shortfall, that must be borne by their owners and shareholders, not by their customers.

Of course, it should always have been like this. Crypto exchanges and platforms should never have been allowed to put their customers’ assets at risk of losses from safeguarding and security failures. And nor should they have been allowed to operate as unlicensed, unregulated shadow banks, leveraging up their customers’ assets while pretending those assets were not at risk. It is a tragedy that the SEC has taken so long to introduce this new guidance. And it is even sadder that it is only guidance. It needs to be much stronger, with strict reporting and control requirements, and severe penalties for infringement. Regulators, it’s time to show your teeth.

Frances Coppola