Introduction

War is like a volcanic eruption in that it both exposes and obscures the clash of powerful forces. When we look at an erupting volcano, our attention is drawn to the spewing forth of red-hot magma and the billowing smoke. But, in reality, the real action and the cause of this visual display is happening deep within the earth. So too with war. We see the drama but may not be aware of the playwrights. The ultimate cause of the violence may be far distant from the action, and the principal scriptwriters may well not wear military uniforms but civilian clothing.

The proximate causes of war may be manifold, but imperialism is often—and evermore increasingly—the strategic driver of conflict. Imperialism is a complex creature with many aspects that shift in importance over time and, sometimes, in variance with each other. Economics may be considered the infrastructure, but it is managed by a superstructure of various components, political, military ethic, civilizational and religious.

In the past, we could talk of inter-imperialist rivalry but substantially, since 1945—and certainly since the collapse of the Soviet Union—there has only been one imperialism, that of the United States. The U.S. has two main challengers, Russia and China, but neither are empires. China, perhaps, may become an empire in time and even achieve dominance, but, for the moment and into the foreseeable future, there is only the United States. U.S. imperialism is arguably faltering and we may be moving back into multipolarity, but that is distinct from contesting imperial powers.

This means that to understand the contemporary world we must analyze U.S. imperialism and recognize its centrality in world affairs. At the time of writing, the war in Ukraine both provides an example and demonstrates the necessity of this analysis. The war is frequently portrayed as one between Russia and Ukraine. It is that, but also more than that. It is essentially a war between the U.S. and Russia, with Kyiv as a proxy. Strategically, it is a product of the U.S. attempt to depower Russia, to a large extent through the expansion of NATO. It is crucial to recognize this in order to understand the war itself. This realization is critically important, as the war in Ukraine is very likely the precursor of a war against China; a war driven by the same imperative of destroying challenges to the imperial power of the United States—but with more fraught consequences for the world.

The U.S. empire is different from its predecessors in two major ways: appetite and self-portrayal. It is the first truly global empire. The sun may have never set on the British empire, but while it had possessions around the world linked by maritime power, its control was patchy, and under threat both from its colonial subjects and from its competitors. Most of the world was outside its dominion. The United States has filled in the gaps: most of the world is within its dominion, and it now looks to space to further its power. All previous empires with some understanding of global geography accepted that rival powers limited and contested their suzerainty. The United States is different. It aspires to the destruction of peer-challengers, and of China and Russia as competitors. It envisages a permanent unipolar world under its domination.

Despite this voracious appetite, the United States portrays itself as an anorexic superpower. It denies any thought of empire, claiming rather that it merely provides—generously and to some degree, reluctantly—indispensable leadership. Its flag flies not over the government buildings of its de facto colonies but only over the embassies and military bases hosted by its supposed allies.

This produces two complementary challenges. The central role of the United States in international affairs must be unearthed and analyzed. Nothing much of consequence happens in the world without U.S. involvement. At the same time, that involvement is hidden, and the U.S. empire’s role obscured or distorted by its huge and largely successful propaganda apparatus. The ongoing Ukraine crisis is a salient example. The root cause is NATO expansion driven by the U.S. as an instrument of its strategy to disempower Russia. The other major players—Russia, Ukraine and the European countries—are subsidiary, and, whether wisely or not, reacting to U.S. grand policy. Needless to say, this is not the way it is portrayed by the United States.

A clear analysis of political structures and dynamics forms a necessary foundation for any activism, from environmental to labor. In a globalized economy no person, whether in their productive or consumer aspect, can ignore U.S. imperialism. The Ukraine crisis has global repercussions. Besides the death and destruction in the Ukraine itself, many people around the world will be impoverished, will lose jobs and suffer unstainable prices increases for oil, gas, wheat, and beyond. Few will be left unscathed—and a few more will get richer.

Centering the United States does not mean ignoring the role of other players and factors, nor does it suggest that U.S. imperialism is omnipotent and eternal. On the contrary, its constraints and decline are an important part of the picture. Nevertheless, it is vital to place the United States at the heart of the world system, and to do this we need to break through the carapace of deception which protects it from scrutiny.

The United States and the Creation of a New Sort of Empire

A hundred years ago, the word empire was frequently used—usually with approbation within the empires themselves—and within what we might call the imperial space. The British empire might compete with and denigrate the Russian empire and vice versa, but neither critiqued the idea of empire itself. Ironically, the one state that did criticize imperialism was the United States, which had just embarked on its own imperial expansion with the Spanish-American War of 1898. That war usually seen as the beginning of that expansion, or at least its overseas aspect. But the United States eschewed the concept of empire and claimed that its expansion was different from that of the others. As Robert Kagan notes, historically, expansion was conceptualized as a reaction to external threat:

Like most expansive peoples—the Greeks and Romans, for instance—Anglo-Americans did not view themselves as aggressors. In part, they believed it only right and natural that they should seek independence and fortune for themselves and their families in the New World. Once having pursued this destiny and established a foothold in the untamed lands of North America, continued expansion seemed to many a matter of survival, a defensive reaction to threats that lay just beyond the ever-expanding perimeter of their English civilization.1

Expansion by the United States was different in many other ways. Outside of the Southern plantations, the expansion was settler-led, as it was in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. This was a familiar historical pattern: nations would displace their neighbors, often by extermination or enslavement, and take their land. However, the main difference between the U.S. and European empires of the time was that the Europeans were seeking resources. This might be embellished with claims of spreading the “word of God,” or of a mission civilisatrice for the French, or of the “white man’s burden” for the British; and operationalized within the framework of inter-imperialist competition, but resources were the keystone.2

Of course, the United States did—and still does—have its version of the European myths. Exceptionalism has proved a rich font, followed by manifest destiny, and then by “making the world safe for democracy.”3 During the Cold War, the anti-communist crusade was the dominant theme and then, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the embrace of the capitalist road in Dengist China, humanitarian intervention and the War on Terror. The current trope is the apocalyptic struggle between “democracy and authoritarianism.”4 Because these terms are devoid of any precise and verifiable meaning, they are admirably positioned to serve as post-modern rallying calls. Vladimir Putin—considered in 2022 to be the bête noire of the United States—wins elections with very substantial majorities over other candidates and has a popularity rating of 83 percent.5 Volodymyr Zelensky, the current poster boy, was very unpopular before the Russian invasion but is presumably riding high on nationalist fervor.6 The regime he inherited came to power after a coup that ousted the democratically-elected president and effectively disenfranchised a substantial part of the population which, in different ways, seceded from Kyiv. Joe Biden, the supremo of the so-called democratic world, only won the 2020 election because he was not Donald Trump, and his poll rating is a fraction of that of his nemesis, Putin.7 All-in-all, it is a rather ramshackle edifice of political inspiration. Overseas proselytizing has also played a strong role; just as the Jesuits and their fellows went out to convert the heathen and guide their rulers, so too does the U.S. empire. The National Endowment for Democracy (NED), the public affairs version of the CIA, has its predecessors in the U.S. Christian missionaries that were active in China and Korea up to the mid-twentieth century. Evangelical Protestantism has both inspired and justified U.S. imperialism:

As one state department official quipped prior to the invasion of Iraq, the Bush White House would probably not have decided to go to war with Iraq if the Gulf’s main product were kumquats instead of oil. And sometimes, such as during the Indian wars of the nineteenth century, religion was merely invoked ex post facto to justify actions that were clearly based on quite different motives. But on major questions involving war and peace—such as the decision to annex the Philippines or go to war in 1917 or 1941—the idea of a chosen nation attempting to transform the world in the face of evil has played a significant role.8

While ideas inspire individuals, systems need more substantial fuel: oil rather than kumquats. For the European empires that was resources—spices, gold and minerals, cotton and silk, labor (through military service or enslavement), coaling stations for ships—and these were primarily acquired through military power. The United States had some of those needs, as symbolized by the Boston Tea Party, but its imperial thrust was distinctly different.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the United States had no great shortage of resources, but it did have burgeoning commercial and industrial ascendancy. There is a parallel here with China, but a contrast with Europe. China, generally speaking, had always been richer than states on its periphery or within its purview, such as the Iranian and Roman empires, and had no incentive for state-sponsored economic expansion. The growth of the modern empire under the Qing Dynasty, from 1644 to 1911, was primarily for security reasons. This applied both to its “Inner Asia Frontiers” (Tibet, Xinjiang, Mongolia) and to the offshore island of Taiwan, which had been held at various times by the Dutch, the Spanish, and by Ming loyalists before being lost to Japan in 1895. The European (and later, Japanese) empires, conversely, had largely become rich and industrialized as a result of empire. The United States, though an avid trader, and willing to use force—or the threat of it in the case of Commodore Matthew Perry and Japan—to force open doors, did not seek a formal empire in order to promote and safeguard trade or resources.9 The “Open Door Policy” of U.S. Secretary of State John Hay was a manifestation of this. Foreign powers, led by the United Kingdom during the first Opium Wars of 1839—42 (which yielded Hong Kong) and followed by France, Germany, Russia, and Japan (whose wars with China yielded Taiwan and Korea), were carving up China in treaty ports and spheres of influence where they had special privileges over their competitors. The United States, with its expanding commercial superiority, was confident of success as long as the door to the Chinese market was open. Hay’s policy, expressed in 1899 and 1900 in notes to the foreign powers, called for China’s territorial and administrative integrity to be preserved. It marked the beginning of a new, non-exclusive form of imperialism, which did not use the word empire.10 This had implications far beyond China, foreshadowing a global transformation where, in V. I. Lenin’s phrase, imperialism was “the highest stage of capitalism.”

U.S. Imperialism: Denial and Centrality

Nevertheless, fashions change and, generally speaking, no one today claims to have an empire, least of all the U.S. government. In the mid-twentieth century, there was a general move from the word war to defense in the labeling of military ministries around the world, but without any substantial change in their function. Many terms are used instead of empire: hegemony, primacy, an indispensable nation, leadership, superpower, unipolarity, the “American century.” One constant theme is that U.S. policy is driven by “good intentions.” This phrase, or a variant of it, is frequently invoked when discussing the devastation inflicted on a foreign country. For instance, in an article in Foreign Affairs entitled “Accomplice to Carnage: How America Enables War in Yemen,” the authors call upon “U.S. officials to candidly reexamine the United States’ posture in the Gulf and recognize how easy it can be, despite the best of intentions, to get pulled into a disaster.”11 There are, of course, exceptions when establishment authors want to be provocative and the words empire or imperial are used gingerly; but usually it is done in order to distance the United States from imperialism. For instance, in 2000, Richard Haass, a diplomat soon to become president of the Council on Foreign Relations (and thus, the authoritative voice of the U.S. foreign policy establishment), wrote:

Americans re-conceive their role from one of a traditional nation-state to an imperial power. An imperial foreign policy is not to be confused with imperialism. The latter is a concept that connotes exploitation, normally for commercial ends, often requiring territorial control. It is grounded in a world that no longer exists, one in which a small number of mostly European states dominated a large number of peoples, most of whom lived in colonies that by definition lacked self-rule.

Such relationships are neither desirable nor sustainable in today’s world. To advocate an imperial foreign policy is to call for a foreign policy that attempts to organize the world along certain principles affecting relations between states and conditions within them. The U.S. role would resemble 19th century Great Britain. Influence would reflect the appeal of American culture, the strength of the American economy, and the attractiveness of the norms being promoted as much as any conscious action of U.S. foreign policy. Coercion and the use of force would normally be a last resort.12

A brave new world indeed, with an empire without exploitation, which uses coercion and force only as a last resort. We might wonder why this mythical, benign entity would need to use coercion and force at all, since it existed not so much for the advantage of the United States but for the benefit of those countries wise enough to recognize the attractiveness of its foreign policy and the education of those that did not. Haass’s paper had been preceded by the destruction of Yugoslavia and followed by the invasions of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya; the carnage in Yemen; and coercion around the world.

And so, we have an empire which denies its existence and which is indeed fairly invisible, particularly in contrast to its predecessors. Indirect rule has long been part of the imperial toolkit—the United Kingdom for instance, used it extensively in India, but this is the first time that it has been elevated to the primary mode of operation. At the same time, the United States is by far the biggest empire in history; one with truly global aspirations and reach. It is necessary, therefore, to center U.S. imperialism in any analysis of world affairs. This does not mean that it is the only factor,—far from it—but in general, there is little that happens without some U.S. involvement, and usually the U.S. is a major player, either directly or through its subordinates.

Too often conflict or war in any particular part of the world is given a local geographic label, and that sticks: we have the Korean War and the Vietnam War. As the word war has gone out of fashion, or was perhaps eased out by the spin doctors, all that is left is the name of the place where the war, or something close to war, was taking place; in recent years, we have had Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria. One thing that links many of these wars—not all of them, but a very definite majority—is that they involve the United States. Sometimes this is a matter of invasion by land (Iraq), sometimes an assault by air (Yugoslavia, Libya) and other times invention through proxy forces, either subversive (Ukraine, 2014) or insurrectionary (Syria). Language can be made to do funny things.13 Thus we have talk of the “Iranian nuclear crisis” and the “North Korean nuclear crisis,” tout court, with no mention of the United States. This might be considered surprising given that the United States is the major player in each situation. Moreover, attaching the word “nuclear” to Iran and North Korea masks the fact that the United States is the strongest nuclear weapons state in the world, while North Korea has a handful and Iran, none at all.14 Sometimes when a war has disputed parentage and contested beginnings, the geographical label provides a necessarily convenient solution; the “Ukraine War” is a case in point.

No discussion of world affairs makes much sense if the United States is not put at the forefront, close to the center. There may certainly be cases where it is not the main player, but as world hegemon, it is never far from center stage. This is not to be taken as meaning that the United States is always the prime mover, or that world events take a course laid down in Washington. The United States is a mighty power, but it is an incoherent one, with limited conscious understanding of the drivers and motivations behind its actions, let alone a grand strategy to preserve its hegemony. Its denialism produces a lack of clarity of thought that hampers the administration of its imperial domain.

One of the curious things about the United States is that it is an open and rich society, relatively unthreatened by either ghosts of the past or external enemies, with huge intellectual resources. The United States probably produces more commentary about itself and its actions in a day than the British Empire in its heyday did in a year, or even a decade. And yet, so much of what is written is specious, lacking self-awareness and claiming an objectivity that it does not possess; virtually all the pundits who feature so prominently in the media explaining to people in the United States (and hence, in much of the world) are inextricably linked to the state, having backgrounds in the military, CIA, think tanks funded by the state or the military-industrial complex (or both), and so forth.15 Even academics become dependent on grants from government or aligned foundations. There are very few independent voices. There is, of course, the web, where the barriers to publishing are very low—but also very often, so are the intellectual standards. Though social media does pose a challenge to the official line propagated by traditional media, censorship in recent years has been eroding access to alternative opinions. This erosion gathered pace (innocently or not) with the COVID-19 pandemic and has grown considerably since the Ukraine War, so much so that one veteran U.S. journalist described the situation in 2022 as worse than McCarthyism.16

Imperial Attributes: the Levers of Power

U.S. imperialism may be new in the sense that it is the first with a truly global reach—it often appropriates to itself the title international community—and yet at the same times it denies its very existence, with the appropriated term serving as camouflage. Even so, it broadly shares the attributes of empire as a political phenomenon. Parallels can be drawn with its predecessors, and the Roman and British empires are the favored comparisons. Its military power will be discussed at some length but first, it is useful to outline some key imperial attributes.

Empires, by definition, are more than a single powerful state but rather a hierarchical collection of states and other political entities, the function of which is to serve the imperial power at the apex. That covers both economic exploitation and political subservience, which are interlinked. Needless to say, these relationships are very complex, with considerable variation over time and specific situation, and subject to constant negotiation at the edges. In general, the relationship is inherently unequal—although there are rare occasions when it might be considered that the subordinate is manipulating the imperial power.17 However, this is an anomaly, and the essential reality is that subordinates—which may be called variously colonies, as in the past, or today, allies and partners—get less than they give. Trump’s besetting sin, in the eyes of the U.S. foreign policy establishment, was that he did not recognize this. He also ignored one of the cardinal rules of imperial management: agglutinate your subordinates so that they follow your leadership in confronting a common enemy. A little bit of friction between them as they compete to display fealty is desirable, too much is dysfunctional; the U.S. has had some difficulty over the years in getting Japan and South Korea to cooperate against China because of the tension between them due to Japanese colonialism. It fondly anticipates that the new “pro-Japanese” administration of Yoon Suk-yeol will remedy that.18 Most important of all is to avoid alienating subordinates so they resent your leadership. Discipline and exploitation, yes, but combined with cajoling and team-building. Trump managed to bring about a deterioration in relations with the leaders, media, and general public of most countries of the empire, and his replacement by Biden was, at least initially, warmly welcomed. However, the empire is too resilient to be much affected by Trump’s boorishness, and subordinates are structurally so locked in that, two academics concluded, they “will put up with more capriciousness, browbeating, and neglect than anyone expected.”19

Curiously, Trump was rather better at that other adage of imperialism, “divide and rule,” than Biden. He tried to be soft on Russia in order to focus on China. However, he was outmaneuvered by his officials, and relations with Russia continued to deteriorate during his term of office.20 He also exposed himself to attack from the Democratic Party and much of the media, as exemplified by Russia-gate. One of the problems with U.S. imperial governance is that there is bipartisan unity on the broad principles of foreign policy—leading to a lack of debate within the system—combined with fierce, unprincipled partisan attacks on specific initiatives, resulting in dysfunctional implementation. Biden, by contrast, could not resist precipitating crisis in Europe, and Secretary of State Antony Blinken is no Henry Kissinger, whose playing of the “China card” in the 1970s was successful in dividing China from the Soviet Union and strengthening U.S. power.21

Power comes in various forms, from hard power (as in military might) to a bewildering array of types of soft power, including education, brain drain, and control over much of the international media. In between, there is diplomatic or political power; the ability, for instance, to get countries to vote in a certain way in the United Nations.

The Power of the U.S. Military

U.S. military power, we are constantly told, is “awesome.”22 One way of quantifying it is by the number of bases it has around the world, with estimates varying from five hundred to one thousand, with definition as a complicating factor, when no other country has more than a handful.23

However, perhaps no single measure better captures U.S. military power and its implications than what is euphemistically called the “defense budget.” According to the International Institute of Strategic Studies—the London think tank often quoted as the authority on such matters, despite the fact its estimates can be dubious—the official U.S. defense budget in 2021 was $754 billion.24 This was four times that of China, twelve times that of Russia, and thirty times that of Iran.25 No figures were given for another supposed “major threat,” North Korea, but clearly the disparity is huge. If we take as true a 2013 South Korean estimate that its neighbor’s defense budget was $1 billion, then the ratio is 754 to 1.26 If we raise that expenditure to $10 billion, the ratio is still a staggering seventy-five times.27 Table 1 gives more details, and Table 2 provides some rough calculations of the ratio between the military expenditures of the United States and its major allies and those of China, Russia, and Iran.

Table 1. Defense Budgets: Top 15 in 2021

| Rank | Country | Defense budget (in billions USD) | Included in U.S. alliance? | Percent of U.S. alliance |

| 1 | United States | 754 | Yes | 62.9 |

| 2 | China | 207.3 | No | 17.3 |

| 3 | UK | 71.6 | Yes | 6.0 |

| 4 | India | 65.1 | Unclear | 5.4 |

| 5 | Russia | 62.2 | No | 5.2 |

| 6 | France | 59.3 | Yes | 4.9 |

| 7 | Germany | 56.1 | Yes | 4.7 |

| 8 | Japan | 49.3 | Yes | 4.1 |

| 9 | Saudi Arabia | 46.7 | Yes | 3.9 |

| 10 | South Korea | 46.7 | Yes | 3.9 |

| 11 | Australia | 34.3 | Yes | 2.9 |

| 12 | Italy | 33.8 | Yes | 2.8 |

| 13 | Iran | 25 | No | 2.1 |

| 14 | Israel | 23.6 | Yes | 2.0 |

| 15 | Canada | 23.2 | Yes | 1.9 |

| Sum of U.S.-allied defense budgets | 1198.6 | |||

Source: John Chipman and James Hackett. “The Military Balance 2022.” (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies), 2022; calculations by Tim Beal.

Table 2: Ratio between the Military Expenditures of the United States and U.S. and its Allies and Those of China, Russia, and Iran

| Ratios | ||

| Country | U.S. | U.S. plus allies |

| China | 4 | 6 |

| Russia | 12 | 19 |

| Iran | 30 | 48 |

Source: John Chipman and James Hackett. “The Military Balance 2022.” (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies), 2022; calculations by Tim Beal.

A slightly different set of figures is supplied by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute gives U.S. military expenditure as in 2020 as $778 billion, estimates for China of $252 billion and for Russia of $62 billion, and Iran of $16 billion.28 The differences in the datasets produced by these reputedly authoritative sources shows that we are in rather imprecise territory, but the preponderance of U.S. military spending is undisputed. Moreover, it is important to take note of the expenditure of U.S. allies, although it is clearly not a matter of mere addition since the ability of the United States to deploy the military power of its allies varies with country and circumstance. Saudi Arabia might be considered a utilizable ally in respect of conflict with Iran, but probably not with China. The United Kingdom and Australia have traditionally been much more willing to put their military at the disposal of the United States than have Germany or France. The only country whose military is under direct U.S. control is South Korea.29 The definition of “ally” is a slippery one. Is India an ally? Washington thought so, hence the 2006 “nuclear deal” between the two countries, despite the pact’s violation of frequently propounded U.S. commitment to non-proliferation.30 More recently, there has been India’s inclusion in the anti-China Quadrilateral Alliance, which has been touted as the beginning of an Asian NATO.31 Nevertheless, India’s reluctance to follow U.S. policy regarding the Ukraine War has shattered that assumption.32 India’s strategic autonomy, which puts its own national interests ahead of compliance with U.S. pressure, has not gone unnoticed in Japan.33

However, military expenditure does not guarantee military superiority, as the U.S. failure to prevail in most of its wars since 1945 demonstrates; only the invasion of Grenada seems to have been an unqualified success—and even that required a rather embarrassing phone call from President Ronald Reagan to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher apologizing for attacking a member of the Commonwealth without consulting London.34 China’s war against Vietnam in 1979 is widely regarded as a failure.35 It is claimed that the Chinese surface fleet would be an easy target for U.S. and Japanese submarines.36 Despite Chinese military expenditures outstripping those of Japan, the Japanese, it seems, still have naval superiority.37

Then there is the intriguing statement by the director of the South Korean Defense Intelligence Agency claiming that North Korea “would win in a one-on-one war,” despite South Korea’s military spending being some thirty-four times that of its rival.38 Clearly, there is some special pleading here; the director is arguing that the existing relationship with the United States is necessary because only with U.S. assistance would they win.

God, it seems, does always favor the big battalions—or at least the biggest military budgets.

Military expenditure may not tell the whole story, but it remains the best single measure of power projection. The United States in recent decades has been able to destroy armies and devastate countries with negligible casualties. Instead, the problems begin during the occupation phase, when guerrilla warfare takes its toll. Whatever the limitation of military spending as an indicator of pacification and long-term control on unruly subjects, it does tell us a lot about motivation, intention, and the political dynamics of the U.S. state.

Geography has given the United States an incredible, unmatched natural defense, with wide oceans to east and west and smaller, subordinate (if sometimes annoyingly disobedient) states to north and south. This natural defense allowed the United States for much of its history up to the mid-twentieth century to have very small military budget and a standing army “modest by international standards.”39 This was labelled “isolationism,” although George Friedman argues that:

But the United States was not isolationist; it was involved in Asia throughout this [inter-war] period. Rather, it saw itself as being the actor of last resort, capable of acting at the decisive moment with overwhelming force because geography had given the United States the option of time and resources.40

Indeed, so-called manifest destiny—originally, an expression of the desire to expand to the Pacific seaboard—was a constant theme from the nineteenth century onward.41 However, this desire did not—or perhaps had no need to—reveal itself in massive, continual military spending until the U.S. entry into the Second World War. The U.S. military budget dropped after the First World War and was set to revert back to previous levels after the Second, but it was rescued by the Cold War and the Korean War, and has scarcely looked back since then. There was a decline after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but that was soon reversed and it does remain inordinately high, far bigger than could be justified by any possible adversary, or even combination of enemies. Indeed, the actual geopolitical situation is somewhat sidelined by what is conventionally, if inadequately, called the Military-Industrial Complex (MIC), a phrase that Dwight D. Eisenhower coined in 1961.42 The crisis in U.S. capitalism after the Second World War has led to both a permanent war economy and the creation of the MIC as a key component. The MIC needs enemies and an empire to defend, but as a business, it has little interest in the details of geopolitics—that is a job for the strategists. As a commercial entity the MIC does not concern itself whether a particular war or state of tension is wise or foolish, let alone the ethics of it all, but whether it produces profit. The MIC is huge and comprises much more than weapons manufactures and soldiers: it encompasses all those who benefit from militarization and miliary spending by the U.S. government and its allies. Prominent in this enterprise are politicians, think tanks, and a large swath of the media. It is thus a very large lobby which complements those who chart U.S. imperial policy and is, needless to say, a generous funder. The MIC does not in itself cause imperialism, but is a tireless promoter of militarization and military solutions to imperialism’s problems.

The U.S. military budget, and the U.S. military itself, tell only one part of the story of imperial coercive power. The U.S. has a considerable array of force multipliers, ranging from allies with substantial (if ineffective) militaries of their own, such as the United Kingdom, through to innumerable proxies: armies that fight their own wars but by so doing serve their patron and funder. These range in size from the very small, through quite substantial (for example, the Kurds), to very large, such as the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU). The AFU has roughly 250,000 troops, the largest in Europe after Russia. Moreover, it receives substantial military assistance, which has exploded since the Russian invasion in 2022; Glenn Greenwald writing in May of that year calculated that “the total amount spent by the U.S. on the Russia/Ukraine War in less than three months is close to Russia’s total military budget for the entire year ($65.9 billion).”43 Unlike allies, which may have to be cajoled into a “coalition of the willing,” proxies are by definition committed to the fight. From their point of view, it is their cause, and they search for patrons to help them achieve their objectives. Proxies benefit from the support of their patrons though the provision of funds, armaments, training, and positive international media exposure. However, there are two elements of relationship that can prove disastrous. First, they are on the front lines and they bear the consequences of enemy action first and, perhaps, alone; patrons can fight proxy wars suffering no casualties of their own, thus avoiding domestic political damage. Second, the patron may have a change of plan and the proxy may become redundant, perhaps even something to be destroyed. The Kurds, amongst many others, are familiar with betrayal by patrons.44

U.S. military power, in its combined manifestations, is a behemoth which straddles the earth like no other. The United States has other strings in its bow. It has a huge economy, only now challenged by China, and a stranglehold over international finance and banking. This makes sanctions both devastating (though not necessarily effective) and, up until now, with the rise of China and the Ukraine War, basically cost-free.45 It has unparalleled diplomatic/political power enabling it to get governments to sacrifice their national interest for U.S. objectives (sanctions and the exclusion of Huawei being two examples). It can manipulate the UN and its agencies. And it has considerable power over the international media enabling it to whip up antagonism, even hysteria, against its enemies, employing information warfare to an Orwellian degree.46 It is the home to many innovative technologies and still has considerable soft power, although this, as with its other forms of power, is faltering.

Indeed, despite the bragging by David Petraeus and Michael O’Hanlon about its “awesome” military power, it may be, paradoxically, its weakest link.

Militarization—America’s Achille’s Heel

Contemporary U.S. military expenditure is far higher than the needs of defense, however generously interpreted, can justify. It is high by historical standards. And it is high in proportion to the economy. Military expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product in the United States is greater, usually considerably greater, than that of comparable countries. “Comparable,” of course, is a key word. A small country faced with a larger adversary will necessarily tend to spend a great proportion of its budget on defense than the larger one. Thus, military expenditure as a percentage of GDP in India, in 2020, is said to have been 2.9 percent, whereas in Pakistan the figure was 4.0 percent (Table 3). We have no hard data on North Korea’s economy or military expenditure, but it is virtually certain that the proportion of the economy devoted to the military is much higher than in that of its southern neighbor.

Table 3: Military Expenditure as Percentage of GDP in 2020, Top 15 Countries

| United States | 3.7 |

| China | [1.7] |

| India | 2.9 |

| Russia | 4.3 |

| United Kingdom | 2.2 |

| Saudi Arabia | [8.4] |

| Germany | 1.4 |

| France | 2.1 |

| Japan | 1.0 |

| South Korea | 2.8 |

| Italy | 1.6 |

| Australia | 2.1 |

| Canada | 1.4 |

| Israel | 5.6 |

| Brazil | 1.4 |

Source: Nan Tian, Alexandra Marksteiner, and Diego Lopes da Silva. “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2020.” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), April 2021.https://www.sipri.org/publications/2021/sipri-fact-sheets/trends-world-military-expenditure-2020. [ ] = SIPRI estimate

The figures in Table 3 are ranked in order of military expenditure. Saudi Arabia is an oil-rich country whose bloated military expenditure has more to do with keeping the United States happy than on any real external threat, and the same goes for the United Arab Emirates. Both Russia and China are smaller economies who are regarded as adversaries by the United States, and do have good reason for a disproportionate arms spending. But only Russia exceeds the United States, and not by much; and this is quite recent (in 2014 the percentage was 3.5, compared with America’s 3.9). It is clear that the United States is very much an outlier, spending a considerably greater proportion of its resources on the military than its geographical and strategic situation justifies. The New York Times has at times, adjured responsible restraint, without giving any reason, beyond pious hope, to believe that this would really happen:

It has been clear for some time that America can no longer afford unrestrained military spending. There is no alternative to making tough decisions about what is essential for the country’s defense and doing a more ruthless and creative job of controlling costs.47

This military expenditure, even if at times slightly shaved back, is still inordinate and diverts resources from areas which would serve U.S. society and economy (and indeed, the national interest) much better. Domestic infrastructure is widely acknowledged to be in a very poor shape, suffered from decades of under-investment.48 President Biden promises to make deep investment in infrastructure “as a way to Counter China,” but skepticism remains.49 As high-speed railway networks expand rapidly in China, in the United States, they “inch along,” again according to the New York Times.50 The U.S. health care system ranks last among eleven high-income countries, claims a 2021 U.S. report on health care in OECD countries.51

With no credible external threat, the United States privileges militarization more than any other country. This was exemplified by the response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak in west Africa. Most countries donated money, or sent medical personnel, with Cuba leading the way on a per capita basis.52 The U.S. response was to send in the military.53 It was not an issue of there being no role for the military; logistics, medical services, and disease control are a key component of any army. The Chinese, for instance, sent a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) field hospital, building on its experience with SARS.54 Instead, it was a question of proportion. The United States, as commentator Joeva Rock put it, was “militarizing the Ebola crisis”:

The U.S. operation in Liberia warrants many questions. Will military contractors be used in the construction of facilities and execution of programs? Will the U.S.-built treatment centers be temporary or permanent? Will the treatment centers double as research labs? What is the timeline for exiting the country? And perhaps most significantly for the long term, will the Liberian operation base serve as a staging ground for non-Ebola related military operations?

The use of the U.S. military in this operation should raise red flags for the American public as well. After all, if the military truly is the governmental institution best equipped to handle this outbreak, it speaks worlds about the neglect of civilian programs at home as well as abroad.55

There is a subtext here which needs to be noted in passing. As Rock suggested, this militarized response to Ebola was consistent with the recent U.S. military penetration of Africa, mainly to counter Chinese commercial ascendancy.56 That in turn has often been wrapped in the robes of “humanitarian intervention,” or, as it is often expressed “the responsibility to protect.”57 At the same time, there has been a conscious public relations effort to emphasis the humanitarian role of the U.S. military in disaster relief—which no doubt has been considerable—in order to mask its fundamental role: the projection of U.S. power. As Robert D. Kaplan pointed out in an article unashamedly entitled “How We Would Fight China”:

The U.S. military’s response to the Asian tsunami was, of course, a humanitarian effort; but PACOM strategists had to have recognized that a vigorous response would gain political support for the military-basing rights that will form part of our deterrence strategy against China.58

The cover of “humanitarian relief” has also been built into U.S. contingency plans for the invasion of North Korea.59

“Humanitarian intervention,” “humanitarian relief,” and the “responsibility to protect” all provide a velvet glove to cover the iron fist. The projection of power, underscored by military power and militarization, is the essential reality.

This reality discomforts many people in the United States. Jeffery Sachs, who might perhaps be described a proponent of the “human face” of U.S. imperialism is concerned that the United States was relinquishing “global leadership” to China. China’s GDP is overtaking that of the United States on a purchasing power parity basis, China is investing heavily in domestic infrastructure and is pushing international banks to develop infrastructure, including the New Development Bank (the BRICS bank), to be based in Shanghai, and the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, to be based in Beijing. It has two major outreach initiatives, the New Silk Road to develop logistics capability and stimulate economic development across Eurasia, and a sea-based version, the Maritime Silk Road.60 Sachs is dismayed by what is happening:

Many European countries are looking to China as the key to stronger domestic growth. African leaders view China as their countries’ new indispensable growth partner, particularly in infrastructure and business development…..

Still, it is striking that just as China is rising economically and geopolitically, the U.S. seems to be doing everything possible to waste its own economic, technological, and geopolitical advantages. The U.S. political system has been captured by the greed of its wealthy elites, whose narrow goals are to cut corporate and personal tax rates, maximize their vast personal fortunes, and curtail constructive U.S. leadership in global economic development. They so scorn foreign assistance that they have thrown open the doors to China’s new global leadership in development financing.

Even worse, as China flexes its geopolitical muscles, the only foreign policy that the U.S. systematically pursues is unceasing and fruitless war in the Middle East. The U.S. endlessly drains its resources and energy in Syria and Iraq in the same way that it once did in Vietnam. China, meanwhile, has avoided becoming enmeshed in overseas military debacles, emphasizing win-win economic initiatives instead. [Emphasis added]61

Sachs has cause to be concerned, but his analysis misses two crucial points. The first, and minor one, is that the Middle East is not the only place that the United States is exercising military muscle. It is the most visible, certainly; but those one thousand bases and that huge military machine straddles the world. More importantly, the projection of military power—and militarization—is but a symptom of a deeper, often malignant, engagement with the world. The veteran journalist Howard H. French bemoans the country’s “military-first” foreign policy:

[America’s] deeply habitual overreliance on military solutions to world problems. The U.S. military long ago supplanted every other part of the U.S. government in overseas engagement—including an atrophied State Department, which has neither the kind of human resources needed to constructively engage with much of the world nor the financial means to have much programmatic impact.62

Sachs is not alone, and in recent years the Quincy Institute has been a vigorous, if rather lonely voice arguing against militarization of U.S. society and foreign policy: “The practical and moral failures of U.S. efforts to unilaterally shape the destiny of other nations by force requires a fundamental rethinking of U.S. foreign policy assumptions.”

Neither Sachs nor the Quincy Institute are isolationist, and the latter makes a specific point of emphasizing that “the United States should engage with the world, and the essence of engagement is peaceful cooperation among peoples. For this reason, the United States must cherish peace and pursue it through the vigorous practice of diplomacy.”63

Fine words, but it is well to bear in mind that seed funding for the Quincy Institute came from George Soros and Charles Koch, capitalists who are anti-militaristic because they see unvarnished brute force as an inefficient way of achieving objectives.64 Moreover, although militarism and the permanent war economy can be seen as essential for capitalism, that does not mean that all individual capitalists or even industries find it beneficial. What is true of an economic system does not necessarily hold for all parts of it. Kinetic war destroys markets and impedes trade, as does economic warfare: physical and financial sanctions. Since the Second World War, this has been manageable because all enemies of the United States have been so much smaller.65 War at this level has been an inconvenience for some capitalists, but not for most, who have, on the contrary, benefited from the economic boost that increase government spending on war provided, even if not in war-oriented industries. It was the Korean War, after all, that rescued the U.S. economy from the doldrums of peace and launched what Seymour Melman labelled the “permanent war economy.”66 The situation began to change in the 2010s as the United States moved to confront a resurgent Russia and rising China. Trump’s trade war against China was the harbinger of things to come, as not only did it fail to bring China to heel, but hurt the United States in ways not felt before—not only poor consumers and small farmers, but also large industries and capitalists. The sanctions unleased during the Ukraine War in 2022, unfolding at the time of writing, are proving even more troublesome. In April 2022, it was reported that Russia was proving resilient to sanctions and U.S. (and international) companies, Koch Industries included, were reluctant to salute the flag and exit the Russian market:

Meanwhile, doubts remain as to how many international companies are committed to withdrawing from Russia. Some major U.S. companies such as International Paper and Koch Industries continue to operate there, as do a slew of European, Indian, and Chinese corporations, including German steel behemoth Thyssenkrupp.

Other companies are already trying to get around the Biden administration’s ban on investment in Russia though legal shenanigans, he [Jeffrey Sonnenfeld of the Yale School of Management, who is leading the Yale disinvestment campaign] said. “It’s frustrating as hell to see that where there are economic sanctions on future investment some companies are trying to fool internal regulatory pressure by saying, for example, this is not new plant equipment, instead we’re just repairing.”67

We may well be at a turning point where U.S. capitalism and its superstructure are increasingly at odds. The immediate needs of imperialism override the interests of large parts of capitalism and ride roughshod over sacred tenets, such as the sanctity of private property. Even though the United States is not officially at war, the country and its subordinate allies routinely steal the assets of individuals (for example, “Russian oligarchs”) and institutions. The United States seizes the assets of Russia, Afghanistan, Venezuela, North Korea without qualms. Although the Quincy Institute might want to return to the days of John Hay when U.S. commercial superiority triumphed, the competitiveness of its corporations is faltering and the state has recourse to kidnapping and fiat prohibitions of competitors. To make some sense of this emerging crisis in U.S. imperialism we need to consider the relationship between international capitalism and imperialism.

International Capitalism and the Stages of Modern Imperialism

John Bellamy Foster considers the turn of the twentieth century a turning point, where one stage was replaced by another:

Already by the late nineteenth century, the contest over colonies that had shaped much of European conflict since the seventeenth century had been replaced by a struggle of a qualitatively new kind: competition between nation-states and their corporations, not for imperial zones, but for actual global hegemony in an increasingly interconnected imperialist world system.68

It might be better considered a period of transition, where, as in Antonio Gramsci’s words, the “old is dying and the new cannot be born.”69 A global order and global market was indeed predicted; in the 1890s, Friedrich Ratzel claimed that “there is in this small planet sufficient space for only one great state.” and in 1919 the British geographer Halford Mackinder foresaw “that in the end [there would be the formation] of a single World-Empire.” However, it was not until 1945 that a single capitalist global market came about, under the power of the United States, and in the 1990s, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and China’s turn to capitalism, that this broke the final barriers and—apart from a few outposts, such as Cuba and North Korea—that true globalization of international capitalism was achieved.

However, this carried within it the seeds of its own dissolution. Not merely was the power of the United States challenged by the survival of Russia and China as independent states, but the supremacy of U.S. capitalism was faltering, largely perhaps by the demands of empire. Capitalism as an economic system had grown to need the permanent war economy for its survival, as an outlet for the surplus that by its nature it could not consume. This was most pronounced in the United States, which was the dominant power and the guarantor of the security of the capitalist world; the provider of pax americana. Competition from the conquered powers, Germany and Japan, was troublesome but manageable; Japan was put in its place by the Plaza Accord of 1985 and so never fulfilled Ezra Vogel’s prediction that it would become “Number One.”70 Despite this use of state power to deal with economic competition, there has been much debate in recent decades about the relative power of corporations and states, much of it getting no further than stating the obvious: large corporations influence their nations’ governments (as the joke has it, “In China the government owns the banks, in America the banks own the government,”) and large corporations are more powerful than small states.71 Most large corporations have linkages with the U.S. government which complicates the analysis. However, the Ukraine War has made it abundantly clear that when it wants to, the U.S. government will exercise its authority over corporations.

However, the measures taken in respect of the Ukraine War were merely a dramatic and very visible instance of a movement which had been in progress for some years, and for which the Plaza Accords were a precursor. As the United States lost competitiveness—especially in respect to China—it turned increasingly to political measures to preserve its position at the apex of the global pyramid. This hegemony, it will be remembered, was based originally on economic superiority. Just as Hay had wanted to break down the barrier erected by the old and declining European empires and create a level playing field on which U.S. commercial strength would prevail, so a century or so later his successors sought to build barriers against the Chinese commercial challenge. The principal, but by no means the only example of this has been Huawei. The giant Chinese company is a leader in many fields, not least in 5G. Apart from this being a large, growing and transformative market, it also has national security implications; the United States had been using its dominance in IT products for years to insert back doors that enable it to spy on friends and foes alike, and there was a concern that China would not only deprive the National Security Agency of this asset, but do the same themselves.72 In reality these fears were probably exaggerated because the United States, as a pioneer, had been able to do things which followers—faced with more knowledgeable clients—could not. Moreover the United States has political power which no others, including China, can match; it is hard to image the United Kingdom taking the same precautions against U.S. companies as it does with Huawei, where it limits Huawei’s market share of the United Kingdom’s non-core 5G network to 35 percent, labels the company a “high-risk” vendor and bars the use of its equipment in core parts of the network, including intelligence, military and nuclear sites.73 The United States has used political power to exclude Huawei from its domestic market and pressured foreign governments, with vary degrees of success, to do likewise. It has also kidnapped a senior Huawei executive, Meng Wanzhou, who is also the daughter of the company’s founder. The basic reason for these actions is that the United States cannot successfully compete with Huawei which, ironically, enjoys the advantages that U.S. companies had in Hay’s time: access to a huge, semi-protected home market and a commitment to research and development, on which, in 2019, it was reported that Huawei was spending $15—20 billion per year.74

As a result of this intervention, there is a move away from the single economic space provided by globalization, with increasingly untrammeled movement of goods, services, and capital (but not people), to a bifurcated world.75 The economies of the United States and those it could take with it would be decoupled from that of China, and supplies lines re-routed.76 The Ukraine War, and the hysteria that it produced, exacerbated the tendency so much so that many pundits opined that globalization was either dead or approaching its end.77

Clearly, the story is not over yet. For one thing, to the degree that decoupling is a result of failure to keep up with China, as time passes the U.S. domain will become poorer and more backward than that led, in some way, by China. Moreover, even if the United States were to retreat into a “Fortress America,” who will follow it? Who will come inside, then realize its implications and try to extract themselves? Who will stay clear in the first place?

Whether U.S. imperialism is in terminal decline or in a transformation which will allow it to weather to storm and preserve hegemony, it is essential to recognize its centrality in the contemporary world. No country, no technology, and no aspect of the global economy is untouched by it.

Ukraine

The Ukraine crisis that erupted in 2022—or 2014, depending on interpretation—illustrates many of the issues raised in this essay. It says a lot about the nature of contemporary U.S. imperialism: how it perceives and how it projects itself; its attributes of power; the utilization of allies, partners and proxies; and the relationship between it and international capitalism. In brief, it expresses:

- S. imperialism, hidden, often unacknowledged but central

- The necessities of myth in:

- Precipitating war

- Creating threat perception

- The use and exploitation of fissures within targeted societies

- The role of subordinates:

- Allies and partners, both countries and institutions such as NATO

- Proxies

- Clients as surrogates and also as inciters with their own agenda

- The role of media and information warfare and its limitations

- Military power and resources, and the propelling power of the MIC

- Contradictions with international capitalism and capitalist legality

Background to the crisis

The Ukraine War of 2022 can be analyzed at two levels:

- The geopolitical: the depowering of Russia as a possible challenger or barrier to global hegemony through its containment, depowering, and probable dismemberment with NATO expansion as the main vehicle

- The local: The use of ethnic division with Ukraine by the United States, its allies in NATO, and by local ethno-nationalists (often labelled neo-Nazis) to generate crisis and precipitate war

Ukraine became independent in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union. However, as Mikhail Gorbachev warned George H. W. Bush, “Ukraine in its current borders would be an unstable construct.” He pointed out that that the ethnically Russian areas of Kharkov and Donbass had been added by local Bolsheviks between the world wars and the Crimea, which was historically part of Russia, had been transferred by Nikita Khrushchev in the 1950s.78 This argument has been made by others, notably Putin in his address on February 24, 2022, announcing what he termed a special military operation (SMO).79 This inherent instability had been manifested and exacerbated during the Second World War, when many Ukrainians fought alongside the Nazis against the Soviet Army.80 The CIA supported the remnants of the anti-Soviet groups after the end of the war and into the 1950s, when the physical enterprise collapsed.81 This was part of a long-running policy of trying to fragment—and hence depower—the Soviet Union, and subsequently the Russian Federation, which started with the Siberian Intervention of 1918—22 and continues until today.

The major geopolitical thrust of U.S. strategy against Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union has been the expansion of NATO, which not merely continues, but has been reinvigorated by the planned accession of Finland and Sweden.82 In theory, NATO was created to block putative (but never actualized) Soviet expansionism. Undeterred by the removal of its primary function, NATO looked to reimagine itself. Bloodied in wars against Serbia, Afghanistan, and Libya, it is now re-orienting toward China.83 However, it is the actual expansion of NATO within Europe, on the borders of Russia, rather than adventures outside its region that has been most consequential so far. Many, on the left, as well as those in the heart of the establishment, warned that NATO expansion might well lead to war, as it has now done.84 Most significantly, William J. Burns, then-ambassador to Russia and now CIA director, warned in a cable to Washington in 2008 that “Nyet means Nyet: Russia’s NATO Enlargement Redlines.” The cable was confidential but is available through WikiLeaks.85

The summary is worth quoting in full because it is doubly instructive. It is prescient in that what it foreshadowed has come about. More importantly, it shows that the highest levels of the U.S. government knew what the results of their policy would be, and presumably wanted to achieve that. The Ukraine War was neither unprovoked nor a surprise; it was the result of deliberate strategic choices in Washington.

Following a muted first reaction to Ukraine’s intent to seek a NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP) at the Bucharest summit (ref A), Foreign Minister Lavrov and other senior officials have reiterated strong opposition, stressing that Russia would view further eastward expansion as a potential military threat. NATO enlargement, particularly to Ukraine, remains “an emotional and neuralgic” issue for Russia, but strategic policy considerations also underlie strong opposition to NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia. In Ukraine, these include fears that the issue could potentially split the country in two, leading to violence or even, some claim, civil war, which would force Russia to decide whether to intervene. Additionally, the GOR and experts continue to claim that Ukrainian NATO membership would have a major impact on Russia’s defense industry, Russian-Ukrainian family connections, and bilateral relations generally. In Georgia, the GOR fears continued instability and “provocative acts” in the separatist regions. End summary.

The fears of GOR—the government of Russia—were well-founded.

A key step in this strategy was the Maidan coup of 2014 that saw the ousting of President Viktor Yanukovych, who had attempted to chart a course between Russia and the West, and his replacement by a more U.S.-friendly government, in which ethno-nationalist forces played a substantial role. The coup was brought about by a combination of these local forces and the manipulations of Victoria Nuland, widely regarded as the architect of U.S. policy towards Ukraine over the last two decades; as Andrew Cockburn put it, the game was on.86

In response, Putin “facilitated” the return of Crimea to Russia, a move very popular among the locals and Russians generally, in order not to lose the naval base at Sevastopol, leased from Ukraine, to NATO.87 The new government in Kyiv brought in various measures discriminating against Russian speakers, and the people of the Russian-oriented Donbass region rebelled, setting up two separatist republics centered on Donetsk and Luhansk. Units deserted to Russia from the Ukrainian army, which was reorganized with U.S. trainers and the incorporation of various private armies and militias such as the Azov Battalion, funded by oligarchs, and a campaign that was to claim at least 13,000 lives over the next eight years was launched against the Donbass.88 The Azov Battalion and other militias are usually labelled “neo-Nazi” because of their obsession with ethnic purity and predilection for violence, to some embarrassment to the U.S. government.89 Like all historical analogies the fit is never exact—for instance both President Volodymyr Zelensky and his patron, Ihor Kolomoisky, are Jewish—but it is close enough to generate vigorous attempts at sanitization, as well as inspiring “white supremacist mass shootings.90 Since 2014 there has been a process of “NATO-ization,” with the United States in the lead, providing weapons and training that has transformed the Ukrainian military—already the largest in Europe outside Russia in terms of personnel—into a major “force multiplier” for the United States:

By 2014 the country barely had a modern military at all. Oligarchs, not the state, armed and funded some of the militias sent to fight Russian-supported separatists in the east. The United States started arming and training Ukraine’s military, hesitantly at first under President Barack Obama. Modern hardware began flowing during the Trump administration, though, and today the country is armed to the teeth.… In this light, mockery of Russia’s battlefield performance is misplaced. Russia is not being stymied by a plucky agricultural country a third its size; it is holding its own, at least for now, against NATO’s advanced economic, cyber and battlefield weapons [Russia is] matched in weaponry—and even outmatched in some cases.91

During 2021 and into 2022 Russia carried out military exercises which were presumably intended to serve as a warning. In December 2021, Russia presented proposals for a new security architecture between it and the West, which were promptly rejected by the Biden administration.92 Despite an incessant media campaign that Russia was planning to invade Ukraine, the bulk of Kyiv’s forces were deployed on the Donbass front and in February 2022, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) observers recorded a substantial increase in artillery attacks on the Donbass.93 Having been criticized for not taking a more decisive stance on the Donbass in 2014, Putin was faced with a call from the Russian Duma on February 15 to recognize the independence of the two Donbass republics. On February 21, he agreed.94 Meanwhile, on February 19, Zelensky had hinted at the annual Munich Security Conference that unless Ukraine was admitted to NATO, it would move to acquire nuclear weapons.95

The scene was set for war.96

Lessons from Ukraine

U.S. imperialism, Hidden, Often Unacknowledged but Central

The Ukraine War is usually portrayed in the Western media as one between Russia and Ukraine with the United States, and its allies—especially those within NATO—as anxious and concerned bystanders, willing to do their duty in helping defend democracy or some such word, but not directly involved.

In fact, the U.S.-led expansion of NATO has been the primary geopolitical driver of the crisis, as its instigating support of the Maidan coup of 2014 destroyed Ukraine’s neutrality and brought about the ascendancy of ethno-nationalist forces whose policies resulted in the reversion of Crimea to Russia and the secession of the Donbass Republic. It has flooded Ukraine with arms and turned the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) into a major military adjunct to U.S. power. It has blocked attempts by Russia, Germany, France, and Ukraine (under Poroshenko) that offered a way to defuse the situation, such as the Minsk Agreements, by giving autonomy to the Donbass while retaining the territorial integrity of Ukraine. Leading liberal journalist Katrina vanden Heuvel suggested that Minsk II was “The exit from the Ukraine crisis that’s hiding in plain sight,” and asked, “isn’t it time for the United States to join with its allies to revive a path to a settlement that might lead to a stable peace?”97 However, it is not in the nature of U.S. imperialism to have “stable peace” when it can have a running sore on the borders of Russia.

The Necessities of Myth

U.S. imperialism is a physical reality, but it is also a constructed imaginary that creates and sustains myths: the myth of its non-existence, the myth of its desire for peace and stability, and the myth of its adherence to international law. It frequently trumpets the rules-based international order (RBIO), which it tries to pass off as a manifestation of international law and the UN Charter, when in fact, it is nothing of the sort. International law is based on equality of sovereign states, but the RBIO privileges the United States and its allies as appropriate, and denies rights to those who resist.98

Two myths are of particular relevance here. One is the U.S. desire for global peace and security. It imagines a pax Americana that is the product of countries voluntarily joining out of fear of common external aggressors, and that peace is only broken when these aggressors—the Soviet bloc, International Communism, Soviet or Chinese expansionism, North Korea (the cast list fluctuates slightly)—attack the United States or its allies; assist others in doing so; or are on the verge of attack, hence requiring a pre-emptive strike. The United States claims it is inherently defensive and peace-loving, and only spends so much on its military so that it can deter those who would violate the peace.

The second myth is that these designated enemies, since they are inherently aggressive, are a threat to all—not merely to the United States, but also to all those countries who huddle (or should huddle) under its protective umbrella.

Elbridge Colby, who, as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy and Force Development in the Trump administration drafted the 2018 National Defense Strategy, published a book in 2021 entitled Strategy of Denial which inadvertently throws interesting light on these two myths.99 Couched inevitably in an Orwellian inversion, wherein the word defense is liberally sprinkled about, Colby implies that the only way to stop China’s rise is a war over Taiwan. In the course of this, he makes two key points. First, war must be precipitated, with the other side maneuvered into firing the first shot. Clyde Prestowitz, a fellow China hawk, describes it thus:

In Colby’s telling, timing would be crucial. The allied forces must always let China make the first move. Indeed, they should do everything possible to ensure that the onus of starting and continuing a war falls on Beijing, which would serve to strengthen the binding between the allies. Colby cites Abraham Lincoln’s genius in maneuvering the South Carolina rebels into firing the first shots at Fort Sumter that started the Civil War. This put the onus of war and destruction on the Confederacy and vastly strengthened support for the war in the Northern states…. China must be put in the position of first to fire and invade.100

This is a familiar device, usually done through a false flag operation, such as the Marco Polo Bridge incident that “legitimized” Japan’s invasion of China in 1937, or the 1964 Bay of Tonkin incident in Vietnam.101 There is a long list of possible cases: the Spanish-American war, the Korean War, the 2003 invasion of Iraq.102 However, it can also be done by applying various forms of pressure so that the opponent decides that war is the only war out. This was probably what was done with Japan in the 1930s, resulting in Pearl Harbor, which was then utilized by Franklin D. Roosevelt to get the reluctant United States into the Second World War II. Henry Simson, Secretary of War, explained the problem: “We face the delicate question of the diplomatic fencing to be done so as to be sure Japan is put in the wrong and makes the first bad move—overt move.… The question was how we should maneuver them into the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves.”103

After noting that Russia, and not Putin alone by any means, regards the expansion of NATO—especially into Ukraine—as an existential threat, Professor John Mearsheimer, a leading international relations specialists United States, argues that U.S. policy was sure to produce war:

I’ve studied the Japanese decision to attack the United States at Pearl Harbor in 1941. I’ve studied the German decision to launch World War I during the July crisis in 1914. I’ve looked at the Egyptian decision to attack Israel in 1973.

These are all cases where decision makers felt they were in a desperate situation and they all understood that in a very important way they were rolling the dice, they were pursuing an incredibly risky strategy, but they just felt they had no choice. They felt that their survival was at stake. So what we’re talking about here is taking a country like Russia, right, that thinks it’s facing an existential threat, that thinks its survival is at stake and we’re pushing it to the limit. We’re talking about breaking it. We’re talking about not only defeating it in Ukraine, but breaking it economically. This is a remarkably dangerous situation, and I find it quite remarkable that we’re approaching this whole issue in such a cavalier way.

Within this process of existential threat, there must be a trigger event. This may be small and only noticeable to the decision-makers; a straw breaking the camel’s back. However, the trigger event may be much more substantial and deliberate. It seems likely that the imminent Kyiv offensive against the Donbass in late February 2022 was such a trigger.

There was an intensive propaganda campaign, led by U.S. intelligence starting in November 2021, claiming that Russia was about to invade Ukraine.104 Then there was a lull, when they claimed that Putin had not made a decision. Then, in mid-February 2022, U.S. embassy staff were withdrawn from Kyiv, and there were statements that an invasion was imminent. This suggests that Washington was aware of Zelensky’s intentions and was perhaps involved in the planning. Putin certainly claims that the imminent offensive made him order the SMO. In early March, U.S. intelligence virtually corroborated this, but claimed that the Kyiv offensive was a “pretext.”105 It is too soon to make a definitive judgment, but it is plausible that the United States, in collaboration with Kyiv, maneuvered or forced Putin into firing the first shot. Subsequent fighting revealed just how strong the UAF, bolstered by NATO arms and training, was, so a preemptive Russian intervention before an offensive gained momentum makes military sense. Putin was also under pressure, manifested in the Duma but presumably stretching much deeper into Russian society, to take firm steps to protect compatriots in Ukraine.106

There is a prima facie case that the special military operation was another Fort Sumter; another Pearl Harbor.

Second, Colby stresses the importance of “allies,” and outlines what he calls a “binding strategy” to harness them in pursuit of U.S. objectives. Utilizing allies and partners as force multipliers is, of course, not new and it has become a leitmotiv, not of the administration he served, but its successor, that of Biden.107 But Colby provides an interesting take on the mechanics of imperial management:

The last part of the book focuses on what Colby calls the “binding strategy,” how to generate the “resolve,” the “strength and determination” needed to “choose to fight” a war. The key point here is how to maneuver China, through “deliberate action,” into appearing extremely threatening to coalition members: “China must not be allowed to precipitate and fight a war over Taiwan or the Philippines in a manner that makes it seem insufficiently threatening to the other regional nation’s vital interests.… The United States…must therefore prepare, posture, and act to compel China to have to conduct its campaign in ways that indicate it is a greater and more malign threat not only to the state it has targeted but to the security and dignity of the other states that might come to its defense.108

Although Colby has Taiwan in mind, the “common threat” ploy has been most evident in respect of Ukraine, and may not, in fact, be as successful against China as he envisaged. However, on the face of it, this device has been extremely successful, with Western European states falling over themselves to sign up against the perceived “Russian threat”: Sweden and Finland reversing long-held (and wise) policies not to join NATO; German doubling its military expenditure; and all of them embroiling themselves in sanctions which promise economic and political turmoil, perhaps disaster. “Perceived” is the operative word because, in reality, as Mearsheimer points out, “the evidence is overwhelming that this is not a case of Putin acting as an imperialist and it is a case of NATO expansion.”109 In other words, Russia is acting to counter what is seen as an existential threat in the Ukraine and has no intention, motivation, or indeed, capability short of full mobilization, to extend the war further. If NATO expansion has produced the crisis, further expansion will surely exacerbate it. In the short term at least, U.S. imperialism has been extremely successful in projecting a mythical common threat to advance its strategic objectives in Europe. However, outside so-called “American Europe” (Hungary and Serbia being resisters on the periphery) and core allies such as Canada, Australia, South, Japan, and New Zealand, much of the rest of the world has not fallen into line, with Saudi Arabia and India being seen as particularly recalcitrant.110

The use and exploitation of fissures within targeted societies

The United States has been ruthless in exploiting ethnic divisions within Ukraine. This is not surprising, since divide and rule is a standard instrument of imperialism and much used within the U.S. toolbox. Ukraine can be divided into at least three parts. First is Crimea, long part of Russia but transferred to Ukraine in the 1950s. Then there is the older Ukraine, which in the word of the scholar Stephen Cohen, “is a diverse country. Western Ukraine looks to Poland and Lithuania, not to Russia. But, nonetheless, much of central Ukraine and almost all of southern Ukraine look to Russia as brethren, as kinfolk, as family.”111

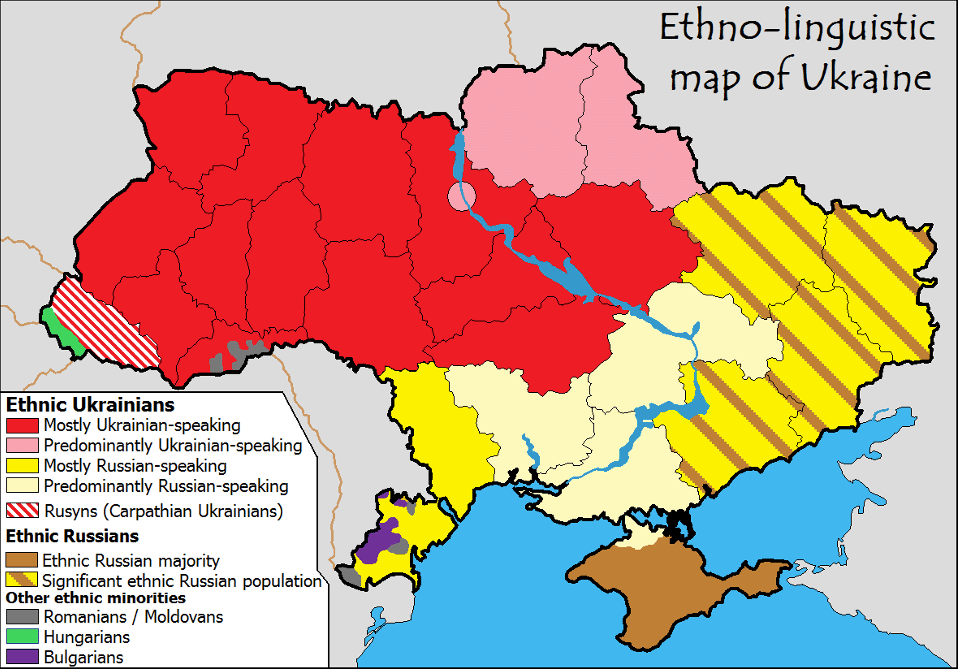

A glance at an ethno-linguistic map of Ukraine shows what a patchwork it is. Not uncommon, of course, as most modern countries bear similar marks of history. The countries of European settlement—especially the Americas and Australia—are different because massive immigration and virtual genocide has obliterated the past.

Source: Yerevanci. “Ethnolinguistic map of Ukraine,” Wikipedia, March 2012, 2012.

This map makes clear that Ukraine could only survive with the territory it inherited from the Soviet Union if it paid due care to the complicated ethnic structure that reflected, in part, its geographical position as a borderland between Russia and the rest of Europe. The latter situation made some sort of neutrality and balancing imperative. The former necessitated a policy which respected ethnic rights, particularly in respect to language. This applied most obviously to ethnic Russians, the largest minority. Moreover, given the huge number of intermarriages between Ukrainians and Russians—Cohen writes of “tens of millions”—distinctions are blurred. This is echoed in bewildered (or disingenuous) Western media accounts of Ukrainians collaborating with Russian forces.112 The media likes to portray the war as a simple, binary conflict between Ukrainians and Russians. The reality is more complicated, and journalists who encounter it struggle to reconcile it with disseminating the official message on which their career depends. For instance, Thomas Gibbons-Neff of the New York Times, reporting from Lysychansk in the Donbass when it was in Ukrainian hands in mid-June 2022, found all the local civilians he spoke to, bar one, were “pro-Russian.” This he put down to Russian propaganda, making no mention of ethnicity or Kyiv’s policies since 2014.113