Ntina Tzouvala

Capitalism as Civilisation: A History of International Law

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2021. 276 pp., $29.99 pb

ISBN 9781108739559

Readers of the first volume of Capital sometimes mistakenly conceptualize capitalism in terms of a relationship between workers and a single capitalist. In doing so they fail to notice that for Marx capitalist society is not one big capitalist enterprise. Rather capitalist society definitionally consists of multiple capitalists and their interactions with each other, ‘their’ employees, and the unemployed (I am grateful to Robert Knox for making this point clearly in a recent conversation). Along similar lines, it is easy to forget that while there is a specifically capitalist form of the state, the capitalist state exists concretely through multiple states and their interactions, as documented and theorized by Marxist accounts of international law.

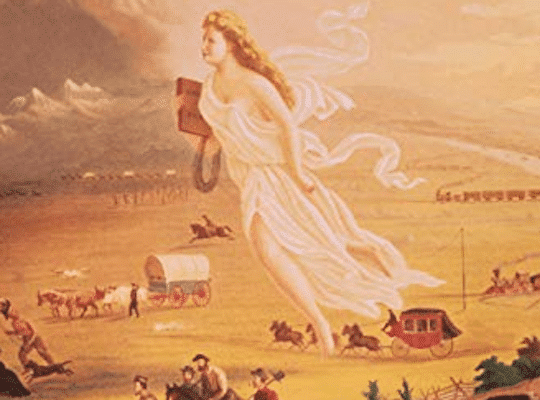

International law played a key role in the historical processes through which capitalist state became a compulsory form of social organization (see Parfitt, 2019). Non-state societies and states judged by international legal standards to be insufficient to capitalist social relations were forced to adopt capitalist state forms or be subjected to conquest by other states, a process regulated and legitimized by international law. Furthermore, existing states are required to remain capitalist in character or become subject to intervention. States navigate their conflict-prone interactions with one another through the mediation of international law.

Now comes Ntzina Tzouvala’s Capitalism as Civilisation: A History of International Law, examining how international law regulates and reproduces the hierarchical relationships among capitalist states. The book does so above all through nuanced historical argument. The first chapter sets out her theoretical approach, drawing on a range of deconstruction, feminist, postcolonial, and above all Marxist theorists. Over the next four chapters Tzouvala uses her theoretical framework to examine several concrete situations, including developments in international law over the 19th century, the League of Nations and mandate system in the aftermath of the First World War, South Africa’s apartheid and colonialism, and the Iraq war. These chapters provide a great deal of detail about a large span of history and demonstrate the usefulness and coherence of the book’s theoretical framework.

Tzouvala provides a fine-grained account of each situation she examines, tracing how power relations and conflicts became the subject of international legal dispute, and in turn how the specifically legal character of that dispute reacted back on the situation. Certainly, history as it actually unfolds must be explained concretely and Tzouvala’s account is admirably granular, getting into detail about each situation she examines. At the same time, she identifies commonalities across these instances, continuities in the ‘standard of civilization’, a pattern of argument, collection of institutionally valid concepts, and set of rhetorical tropes within international law. In doing so, Tzoubala makes clear that international law is not a neutral instrument but rather institutionalizes the compulsory character of capitalist social relations and the capitalist form of the state.

The standard of civilization is the benchmark for inclusion as a state among states within the global legal order. Think of the phrase ‘failed state’, which implies corresponding successful states and a framework defining success and failure. The standard of civilization is part of that framework, and one important in the histories of colonization, decolonization, and imperialism. Explicit reference to the ‘standard’—the explicit labeling of some people as ‘uncivilized’—has declined over time, but as Tzouvala demonstrates that is more change of rhetoric than change in social reality. The standard sets a bar that any polity seeking to be validated as a state must clear.

Tzouvala stresses both that the ‘standard of civilization’ as legal argument was involved in each conflict she examines, and that her account of the logic of this part of international law does not exhaustively explain events on the ground. That is to say, there are still contingencies. Tzouvala’s account provides an explanation of the backdrop within which the situations she analyzes existed and the limited set of possible outcomes in that situation. She calls this ‘structured indeterminacy’ (215), meaning that in a given situation capitalist social relations limit what outcomes are possible, yet what capitalism-compatible outcome occurs is genuinely open-ended. That outcomes are both structured and, within that structure, indeterminate, is important for two reasons: people who participate in or study conflicts over different possible outcomes within capitalism are right to experience those conflicts as open-ended and high stakes. At the same time, such conflicts only end with some version of capitalism, with all the negative elements built into capitalist society still present. Tzouvala’s framework can account for all of these realities.

By tracing different concrete historical situations in the book, Tzouvala makes clear that the standard of civilization as been dynamic in two senses. First, the standard changed over time as notions of civilization changed. Tzouvala notes, for example, that the rise of the welfare state within dominant states led to making the presence of a recognizable welfare state a mark of civilization. Second, the standard did not necessarily indicate permanent exclusion from or subordination with the global legal order, because civilization was a historical condition that could be achieved. This is an element of what Tzouvala calls the ‘logic of improvement’ (43). A state could be barred from full and equal status by not being improved enough, so to speak, but further improvement remained possible—and indeed, was rendered compulsory. This logic also implied some degree of minimal restraint upon colonizing powers, as they were required to at least rhetorically present evidence of uplifting the people they colonized. This is not at all to believe colonizers’ claims of civilizing mission, but rather to say that under international law colonizers were compelled to make such claims and present some degree of evidence, which was subject to dispute.

Tzouvala argues throughout the book that the standard of civilization has tended to be expressed not only through the logic of improvement, but also through what she calls the ‘logic of biology’ (45). The logic of biology opposes the (mild, relative) dynamism implied in the logic of improvement, holding instead that certain people are simply fixed, frozen in time, inherently incapable of being even notional equals with the dominant powers of the world system. Over time the logic of biology faced serious challenges from decolonial and other movements, making this logic less acceptable to declare openly. Instead, the logic has taken a turn toward the cultural, which offered other reasons to make claims functionally equivalent to biological racism. (Tzouvala’s book here could be read productively in tandem with Balibar and Wallerstein, 1991, on the pattern of reifying culture as a permutation of racism.)

Tzouvala argues at length that international law has tended to exist over time in the form of a movement back and forth between the logics of biology and improvement with arguments in international law about one such logic tending to give rise to the other, and vice versa. This can be understood as international law having a contradictory character, in keeping with the general Marxist sense that capitalism’s reproduction is a contradictory process. Indeed, Tzouvala argues that the contradictory logics that constitute the standard of civilization represent different ways of conceptualizing the contradictory processes of capitalism’s reproduction.

The book focuses primarily on what actually happened, as is appropriate for a work of historical scholarship. I should say, this is a history that runs up to what is essentially the present day. Tzouvala’s chapter on Iraq and Syria in the early 2000s argues that the standard of civilisation continues to constrain possibilities today. Indeed, the standard takes on a particular ferocity in the context of neoliberalism, where civilisation in effect comes to mean willingness to impose neoliberal policies: to refuse neoliberalism is to risk falling outside the international law-imposed configuration of good government in the present.

While the book is historically-focused, in an especially thought-provoking moment, Tzouvala builds on her inquiry to gesture toward alternative avenues that capitalism could have taken. She points out that European countries developed specific forms of institutions, and above all approaches to statecraft, through which to organize capitalist social relations. Over time, the predominance of these countries in the international system of states not only made capitalism and the capitalist state compulsory, but also made dominant states’ specific approaches to institutionalizing capitalist social relations compulsory. The implication is that there has been a historical potential for different versions of capitalism than the versions that have become dominant. While Marxists generally emphasize opposing capitalism per se, not only specific versions thereof, the idea of serious institutional variation within capitalism is important for sorting out what it actually means to oppose capitalism as such. (This is especially relevant in the United States, which in recent years has witnessed a renovation of New Deal liberalism and left populism that refers to itself as democratic socialism.) Tzouvala does not develop this point at great length, again as is appropriate given her focus on what actually happened in the history of international law, but the point stands as an example of how her carefully argued scholarship is good to think with and opens up questions and lines of inquiry beyond its immediate object.

The picture that emerges over the course of the book is one of international law as a tension-laden field of ideology and institutions, offering a range of arguments that can be made—and institutional means for dealing with these arguments—for the purposes of relatively orderly resolution of disputes over the distribution of rights, responsibility, and resources between states. These arguments in the law are not simply lying around available to be taken up by international lawyers however they like. Rather, changing historical conditions—as with the example of the development of welfarism changing the standard of what counts as a civilized state—constrain the available positions. So too do the arguments of other actors: if we think of international law as a chess board, players must respond to, and so are in a sense limited by, each other’s moves.

From a Marxist perspective, this is a game that to an important extent cannot be won, since international law offers only capitalism-compatible outcomes. As Tzouvala notes, within each of the conflicts she examines international law placed a ceiling on the possibilities of revolutionary emancipation. The latter point is well-made and important, but I wished it was made a little more forcefully and at more length, though of course I understand an author can only do so much in a single book. A less than careful reader might come away missing that the oppositional figures the book treats (i.e., the actors especially subordinated within the legal conflicts the book examines and whom the book generally treats sympathetically) represented foreclosed possibilities and potential alternative directions for historical development specifically within capitalism, rather than possibilities for exit from or abolition of capitalism.

International law allows states to navigate their interactions with each other by making claims in response to problems that arise from contradictions within global capitalism, and to do so in ways that preserve capitalist social relations. International law, then, is a means by which state actors jockey for position in our capitalist present. Anti-capitalist futures must be created elsewhere. That said, the stakes of in-capitalism conflicts are very high for the people involved, which is part of the why international law has the power it does. Indeed, capitalism’s reproduction over time occurs through conflicts. Readers seeking to understand the role of law in these conflicts will learn a great deal from Tzouvala’s admirable book.

References

- 1991 Race, Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities London: Verso

- 2019 The Process of International Legal Reproduction: Inequality, Historiography, Resistance Cambridge: Cambridge University Press